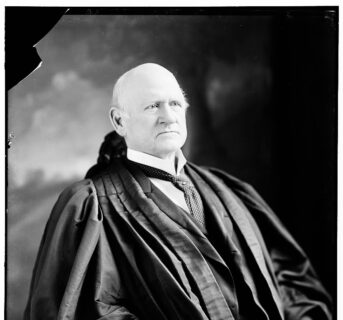

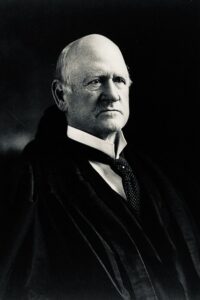

Can the Constitution be Colorblind? On the Farsighted Constitutionalist, Justice John M. Harlan

The current obsession on race in politics and society demands that we reexamine the 1896 Supreme Court dissent that took most seriously the notion of a “colorblind constitution.” Its author is the Justice whose passing 110 years ago we memorialize, John Marshall Harlan (1833-1911).

Harlan’s dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson has become an iconic moment in the long struggle for civil rights. His opinion voiced the highest aspirations of the American political tradition. But the colorblind standard and disturbing statements in his opinion have spurred a second, critical look at his words. My thoughts that follow encourage yet another look.

Harlan’s background would not presage a distinguished name in civil rights. After rising in Kentucky politics to become its Attorney General, he served on the Supreme Court from 1877-1911. His political party background included the Whigs, the Know-Nothings, and the Constitution Union Party. A slaveholder, he nonetheless recruited a pro-Union regiment in the Civil War. He opposed Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and supported Democrat and retired Union army general George McClelland for president in 1864. (One should recall that Lincoln gathered few votes in Kentucky in both his presidential races, winning less than 1% of the vote in 1860 and 30% in 1864.) Renouncing his previous opposition to the 14th and 15th amendments, he became a Republican in 1868 and supported Rutherford Hayes for president in 1876 and was rewarded with an appointment to the Supreme Court in 1877.

The Plessy Decision

In the Plessy litigation and in the view of the Supreme Court the legal consensus was that it was “reasonable regulation” by a State to enforce a law mandating racial segregation on railway cars. Thus, the Court held that the Reconstruction Amendments were irrelevant to the mulatto passenger Homer Plessy. As Justice Henry Brown wrote for the Plessy eight-justice majority: “… in the nature of things, [the 14th amendment] could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based upon color, or to enforce social, as distinguished from political, equality, or a commingling of the two races upon terms unsatisfactory to either.” Not just the South but the whole country accepted racial segregation in public schools.

Government should be limited, Brown argued, in what it promises people. Therefore,

Legislation is powerless to eradicate racial instincts, or to abolish distinctions based upon physical differences, and the attempt to do so can only result in accentuating the difficulties of the present situation. If the civil and political rights of both races be equal, one cannot be inferior to the other civilly or politically. If one race be inferior to the other socially, the constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane.

Harlan’s Dissent

Harlan began his reply to the majority by proposing that a robust interpretation of the 13th amendment alone might have banned state segregation laws and even more. “The thirteenth amendment …. not only struck down the institution of slavery as previously existing in the United States, but it prevents the imposition of any burdens or disabilities that constitute badges of slavery or servitude. It decreed universal civil freedom in this country.”

By “badges of slavery or servitude” Harlan meant the vestiges of slavery reincarnated in postbellum state practices that replicated slavery, through restrictive labor practices or public segregation for example. Harlan’s 13th amendment meant more than mere release from bondage. It restricted the reach of the former masters as it protected the former slaves, for the abolition of slavery meant the end of the master class as well. Therefore, “Jim Crow”—legal segregation of the races—violates the 13thamendment. And to this was added the 14th amendment, with its privileges or immunities, equal protection, and due process clauses, which sought to protect blacks more specifically by enumerating rights, equalizing them, and making them substantive, that is, preventing government interference with them. “These two amendments, if enforced according to their true intent and meaning, will protect all the civil rights that pertain to freedom and citizenship.”

In this context Harlan made his argument for the unreasonableness, indeed irrationality, of segregation laws and their unconstitutionality under a constitution to which the Civil War restored the authority of the Declaration of Independence. Harlan’s latter-day critics attack Harlan because of his deference to the fact of white dominance. Yet, they fail to see his ridicule of the majority opinion’s reliance on opposition to “social equality.”

The white race deems itself to be the dominant race in this country. And so it is, in prestige, in achievements, in education, in wealth, and in power. So, I doubt not, it will continue to be for all time, if it remains true to its great heritage, and holds fast to the principles of constitutional liberty. But in view of the constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law….

In my opinion, the judgment this day rendered will, in time, prove to be quite as pernicious as the decision made by this tribunal in the Dred Scott Case.

In Defense of Harlan

Here, I would claim against Harlan’s critics, that Harlan trumps the majority’s dismissal of Plessy’s claim to equal treatment. The majority dismissed Plessy’s claim because “social equality” was beyond the power of the constitution to produce. In response, Harlan distinguished between sociological fact and political imperative. When Harlan writes that the white race may perpetually enjoy oligarchic “dominance” on the condition that “it remains true to its great heritage, and holds fast to the principles of constitutional liberty,” he points toward the principles and heritage that reach their apex in the Declaration of Independence’s self-evident truth that all men are created equal. This is part of a particular nation’s birth, but it is a truth for all nations. The dominant white race needs to look inside and past itself. The “white race” is in fact a diverse collection of nationalities or ethnicities, not to mention ages, characters, and sexes. The existence of blacks allowed all these groups to redefine themselves as a “white” race, spurred on, for example, by Stephen Douglas’s racial demagoguery, as pointed out by Lincoln.

The concept of a colorblind constitution needs rescue from facile misinterpretation. First, it is frequently confused today for “colorblind society,” which would be an absurdity, as much as an incorporeal society would be. But a colorblind constitution means that the body politic is not based on castes or classes because the Declaration bases legitimate government on individual rights. The colorblind constitution reflects Aristotle’s notion that law is reason (logos) free from passion. Of course, politics is very much a sensual, passionate activity, as Aristotle, Machiavelli, and Madison fully realized. Constitutions and constitutionalism exist to restrain the passions of politics. In this view, the greatest protection for citizens under a colorblind constitution is a restrained government that recognizes the need for a private sphere of freedoms protected from government power.

The absurdity of a government of castes becomes clearer when Harlan in his dissent introduces the example of an immigrant, a “Chinaman,” who can occupy the “white” railway car, while black Civil War veterans may not. A constitution that affords aliens rights that are denied to fellow citizens betrays republican government.

It is not the least of its virtues that Harlan’s dissent replicated Lincoln’s prudence. The Great Dissenter’s political career in Kentucky and his time on the Court justified the Great Emancipator’s Kentucky policies.

Bibliography

The best book on Plessy v. Ferguson remains Charles Lofgren, The Plessy Case (Oxford University Press, 1987).

Harry V. Jaffa, A New Birth of Freedom (Rowman and Littlefield, 2000).