No related resources

Introduction

American designs on Cuba, as we have seen in this collection (See Annual Message (Monroe Doctrine), The Ostend Manifesto, Special Message Regarding the Annexation of Santo Domingo), were both ancient and abiding. Another opportunity for acquiring the “Pearl of the Antilles” presented itself in 1895, when the Cuban people rebelled and fought to remove their Spanish colonial overseers. This rebellion was harshly suppressed, and the American press was full of the details of this Old World repression of New World citizens.

Upon taking office in 1897, President William McKinley immediately focused on the Cuban problem, keeping his own counsel and excluding the State Department from much of his decision-making process. McKinley’s party had drafted a bluntly expansionist platform during the election of 1896, but President McKinley wavered at times from this position, offering to mediate between Spain and Cuba in a quest to achieve some measure of autonomy for the Cuban people and Spain’s commitment to treat them humanely. Spain sought to delay any discussions of this sort, fearing the loss of Cuba as the final blow to a dying empire, while members of the Cuban insurgency refused any offer that fell short of a complete break. These fruitless efforts led the expansionist lobby to conclude that McKinley was passive and indecisive, although these assessments proved to be unfounded.

Events soon took a turn in favor of those calling for American intervention in Cuba. In February 1898, operatives for a Cuban independence movement intercepted a private letter written by the Spanish envoy in Washington. The letter, which was critical of McKinley’s character and described him as weak, was handed over to the Hearst newspapers and immediately published. Shortly after that, the USS Maine exploded in Havana Harbor killing more than 260 sailors. The cause of the explosion remains in dispute but was likely not sabotage. (Naval historians mostly agree that the cause was a coal dust explosion in the coal bunkers). The combined impact of these events led in the United States to demands for war, as “Remember the Maine, to Hell with Spain” became a popular battle cry.

Even after these affronts to America’s honor, McKinley continued his restrained approach. He submitted a measured report on the sinking of the Maine and use mild diplomatic language urging Spain to leave Cuba. But the press kept up a steady drumbeat for war. Theodore Roosevelt, itching for military glory, harshly criticized McKinley’s restraint, claiming that the president “had no more backbone than a chocolate éclair.” McKinley’s vice president, Garret Hobart, warned the president that he needed to get in front of this issue or Congress might go ahead and declare war without his involvement.

To this day, historians disagree as to why McKinley came around to favoring war with Spain. Was it the arguments of Vice President Hobart or other Republican officials, or did he have some other motive? Several historians contend that McKinley was stampeded into war by congressional and public pressure. Others contend that McKinley mistrusted both Spain and the insurgents who were fighting to topple Spanish rule and decided to intervene to prevent either side from prevailing and harming American interests on the island.

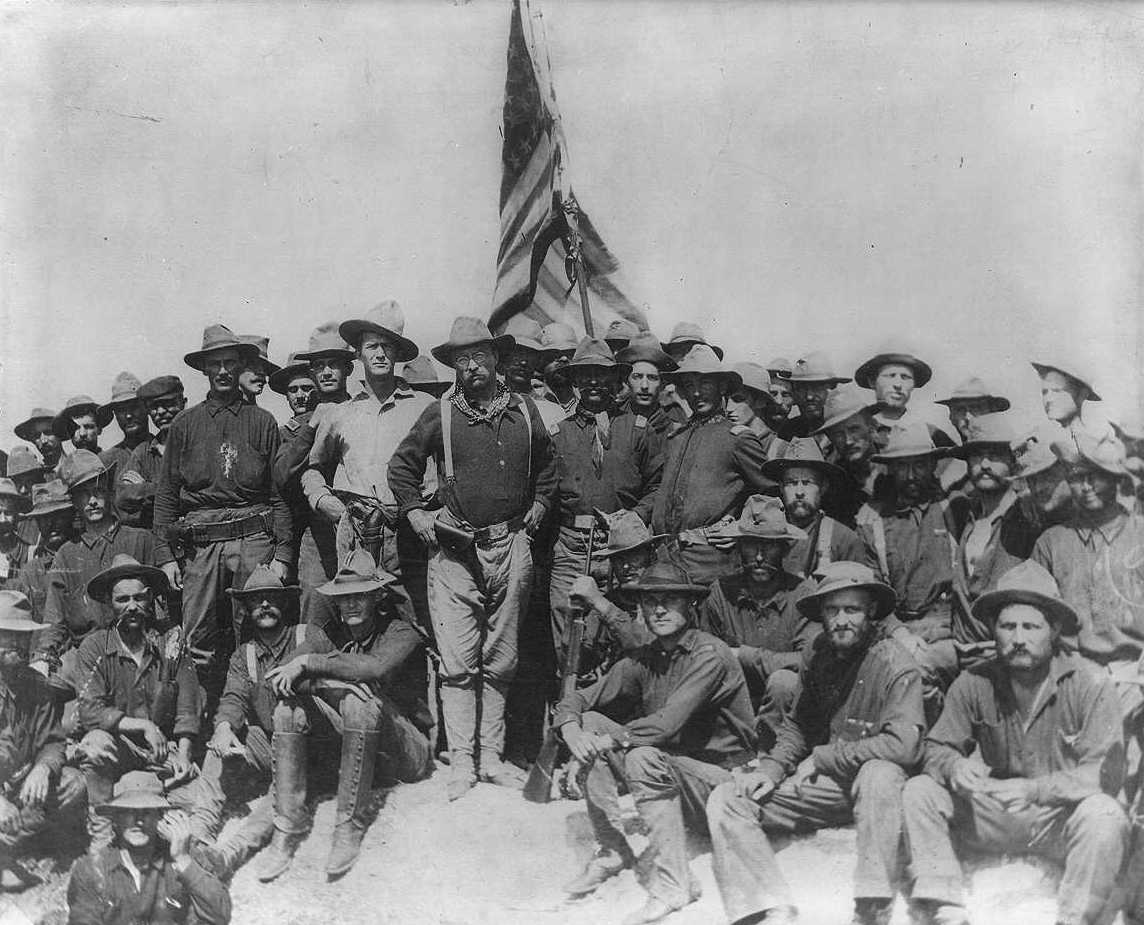

Whatever the rationale, President McKinley submitted a request to Congress to permit him to intervene in Cuba. The request was approved two days later, but Congress attached an amendment to this legislation prohibiting the United States from annexing Cuba. On April 22, President McKinley announced that the United States would begin blockading Cuban ports, which in turn led Spain to declare war. The United States followed suit with its own declaration on April 25, 1898. “The Splendid Little War,” as Secretary of State John Hay described it, was under way.

Congressional Record (bound edition), vol. 31, pt. 4, 55th Congress, 2nd session, 3698–3724, available at https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/GPO-CRECB-1898-pt4-v31/GPO-CRECB-1898-pt4-v31-16.

Obedient to that precept of the Constitution which commands the president to give from time to time to the Congress information of the state of Union and to recommend to their consideration such measures as shall be judged necessary and expedient,1 it becomes my duty now to address your body with regard to the grave crisis that has arisen in the relations of the United States to Spain by reason of the warfare that for more than three years has raged in the neighboring island of Cuba.

I do so because of the intimate connection of the Cuban question with the state of our own Union and the grave relation the course which it is now incumbent upon the nation to adopt must needs bear to the traditional policy of our government if it is to accord with the precepts laid down by the Founders of the republic and religiously observed by succeeding administrations to the present day.2

The present revolution is but the successor of other similar insurrections which have occurred in Cuba against the dominion of Spain, extending over a period of nearly half a century, each of which, during its progress, has subjected the United States to great effort and expense in enforcing its neutrality laws, caused enormous losses to American trade and commerce, caused irritation, annoyance, and disturbance among our citizens, and by the exercise of cruel, barbarous, and uncivilized practices of warfare, shocked the sensibilities and offended the humane sympathies of our people.

Since the present revolution began in February 1895, this country has seen the fertile domain at our threshold ravaged by fire and sword in the course of a struggle unequaled in the history of the island and rarely paralleled as to the numbers of the combatants and the bitterness of the contest by any revolution of modern times where dependent people striving to be free have been opposed by the power of the sovereign state.

Our people have beheld a once prosperous community reduced to comparative want, its lucrative commerce virtually paralyzed, its exceptional productiveness diminished, its fields laid waste, its mills in ruins, and its people perishing by tens of thousands from hunger and destitution. We have found ourselves constrained, in the observance of that strict neutrality which our laws enjoin, and which the law of nations commands, to police our own waters and watch our own seaports in prevention of any unlawful act in aid of the Cubans.

Our trade has suffered; the capital invested by our citizens in Cuba has been largely lost, and the temper and forbearance of our people have been so sorely tried as to beget a perilous unrest among our own citizens which has inevitably found its expression from time to time in the national legislature, so that issues wholly external to our own body politic engross attention and stand in the way of the close devotion to domestic advancement that becomes a self-contained commonwealth whose primal maxim has been the avoidance of all foreign entanglements. All this must need awaken, and has, indeed, aroused the utmost concern on the part of this government, as well during my predecessor’s term as in my own.

In April 1896, the evils from which our country suffered through the Cuban war became so onerous that my predecessor made an effort to bring about a peace through the mediation of this government in any way that might tend to an honorable adjustment of the contest between Spain and her revolted colony, on the basis of some effective scheme of self-government of Cuba under the flag and sovereignty of Spain. It failed through the refusal of the Spanish government then in power to consider any form of mediation or, indeed, any plan of settlement which did not begin with the actual submission of the insurgents to the mother country, and then only on such term as Spain herself might see fit to grant. The war continued unabated. The resistance of the insurgents was in no wise diminished.

The efforts of Spain were increased, both by the dispatch of fresh levies to Cuba and by the addition to the horrors of the strife of a new and inhuman phase happily unprecedented in the modern history of civilized Christian peoples. . . .

By the time the present administration took office a year ago, reconcentration3—so called—had been made effective over the better part of the four central and western provinces, Santa Clara, Matanzas, Havana, [and] Pinar del Rio.

The agricultural population to the estimated number of 300,000 or more was herded within the towns and their immediate vicinage,4 deprived of the means of support, rendered destitute of shelter, left poorly clad, and exposed to the most unsanitary conditions. As the scarcity of food increased with the devastation of the depopulated areas of production, destitution and want became misery and starvation. Month by month the death rate increased in an alarming ration. By March 1897, according to conservative estimates from official Spanish sources, the mortality among the reconcentrados from starvation and the diseases thereto incident exceeded 50 per centum of their total number.

No practical relief was accorded to the destitute. The overburdened towns, already suffering from the general dearth, could give no aid. So called “zones of cultivation” established within the immediate areas of effective military control about the cities and fortified camps proved illusory as a remedy for the suffering. The unfortunates, being for the most part women

and children, with aged and helpless men, enfeebled by disease and hunger,

could not have tilled the soil without tools, seed, or shelter for their own

support or for the supply of the cities. Reconcentration, adopted avowedly

as a war measure in order to cut off the resources of the insurgents, worked

its predestined result. As I said in my message of last December, it was not

civilized warfare; it was extermination. The only peace it could beget was

that of the wilderness and the grave. Meanwhile the military situation in the island had undergone a noticeable change. The extraordinary activity that characterized the second year of the war, when the insurgents invaded even the thitherto unharmed fields of Pinar del Rio and carried havoc and destruction up to the walls of the city of Havana itself, had relapsed into a dogged struggle in the central and eastern provinces. The Spanish arms regained a measure of control in Pinar del Rio and parts of Havana, but under the existing conditions of the rural country, without immediate improvement of their productive situation. Even thus partially restricted, the revolutionists held their own, and their conquest and submission, put forward by Spain as the essential and sole basis of peace, seemed as far distant as at the outset.

In this state of affairs my administration found itself confronted with the grave problem of its duty. My message of last December reviewed the situation and narrated the steps taken with a view to relieving its acuteness and opening the way to some form of honorable settlement. The assassination of the prime minister, Canovas,5 led to a change of government in Spain. The former administration, pledged to subjugation without concession, gave place to that of a more liberal party, committed long in advance to a policy of reform, involving the wider principle of home rule for Cuba and Puerto Rico.

The overtures of this government, made through its new envoy, General Woodford,6 and looking to an immediate and effective amelioration of the condition of the island, although not accepted to the extent of the condition of the island, although not accepted to the extent of admitted mediation in any shape, were met by assurances that home rule, in advanced phase, would be forthwith offered to Cuba without waiting for the war to end, and that more humane methods should thenceforth prevail in the conduct of hostilities. Coincidentally with these declarations, the new government of Spain continued and completed the policy already begun by its predecessor, of testifying friendly regard for this nation by releasing American citizens held under one charge or another connected with the insurrection, so that by the end of November not a single person entitled in any way to our national protection remained in a Spanish prison.

While these negotiations were in progress the increasing destitution of the unfortunate reconcentrados7 and alarming mortality among them claimed earnest attention. The success which had attended the limited measure of relief extended to the suffering American citizens among them by the judicious expenditure through the consular agencies of the money appropriated expressly for their succor by the joint resolution approved May 24, 1897, prompted the humane extension of a similar scheme of aid to the great body of sufferers. A suggestion to this end was acquiesced in by the Spanish authorities. On the 24th of December last I caused to be issued an appeal to the American people, inviting contributions in money or in kind for the succor of the starving sufferers in Cuba, following this on the 8th of January by a similar public announcement of the formation of a central Cuban relief committee, with headquarters in New York City, composed of three members representing the American National Red Cross and the religious and business elements of the community.

The efforts of that committee have been untiring and have accomplished much. Arrangements for free transportation to Cuba have greatly aided the charitable work. The president of the American Red Cross and representative of other contributory organizations have generously visited Cuba and cooperated with the consul-general and the local authorities to make effective distribution of the relief collected through the efforts of the central committee. Nearly $200,000 in money and supplies has already reached the sufferers and more is forthcoming. The supplies are admitted duty free, and transportation to the interior has been arranged so that the relief, at first necessarily confined to Havana and the larger cities, is now extended through most if not all of the towns where suffering exists. . . .

The war in Cuba is of such a nature that short of subjugation or extermination a final military victory for either side seems impracticable. The alternative lies in the physical exhaustion of the one or the other party, or perhaps of both—a condition which in effect ended the ten years’ war by the truce of Zanjon.8 The prospect of such a protraction and conclusion of the present strife is a contingency hardly to be contemplated with equanimity by the civilized world, and least of all by the United States, affected and injured as we are, deeply and intimately, by its very existence.

Realizing this, it appeared to be my duty, in a spirit of true friendliness, no less to Spain than the Cubans who have so much to lose by the prolongation of the struggle, to seek to bring about on immediate termination of the war. To this end I submitted, on the 27th ultimo,9 as a result of much representation and correspondence, through the U.S. minister at Madrid, propositions to the Spanish government looking to an armistice until October 1 for the negotiation of peace with the good offices of the president.

In addition, I asked the immediate revocation of the order of reconcentration, so as to permit the people to return to their farms and the needy to be relieved with provisions and supplies from the United States, cooperating with the Spanish authorities, so as to afford full relief.

The reply of the Spanish cabinet was received on the night of the 31st ultimo. It offered, as the means to bring about peace in Cuba, to confide the preparation thereof to the insular parliament,10 inasmuch as the concurrence of that body would be necessary to reach a final result, it being, however, understood that the powers reserved by the constitution to the central government are not lessened or diminished. As the Cuban parliament does not meet until the 4th of May next, the Spanish government would not object, for its part, to accept at once a suspension of hostilities if asked for by the insurgents from the general in chief, to whom it would pertain, in such case, to determine the duration and conditions of the armistice.

The propositions submitted by General Woodford and the reply of the Spanish government were both in the form of brief memoranda, the texts of which are before me. . . .The function of the Cuban parliament in the matter of “preparing” peace and the manner of its doing so are not expressed in the Spanish memorandum; but from General Woodford’s explanatory reports of preliminary discussions preceding the final conference it is understood that the Spanish government stands ready to give the insular congress full powers to settle the terms of peace with the insurgents—whether by direct negotiation or indirectly by means of legislation does not appear.

With this last overture in the direction of immediate peace, and its disappointing reception by Spain, the executive is brought to the end of his effort. . . .

I said in my message of December last, “It is to be seriously considered whether the Cuban insurrection possesses beyond dispute the attributes of statehood which alone can demand the recognition of belligerency in its favor.” The same requirement must certainly be no less seriously considered when the graver issue of recognizing independence is in question, for no less positive test can be applied to the greater act than to the lesser; while, on the other hand, the influences and consequences of the struggle upon the internal policy of the recognizing state, which form important factors when the recognition of belligerency is concerned, are secondary, if not rightly eliminable, factors when the real question is whether the community claiming recognition is or is not independent beyond peradventure.

Nor from the standpoint of expediency do I think it would be wise or prudent for this government to recognize at the present time the independence of the so-called Cuban Republic. Such recognition is not necessary in order to enable the United States to intervene and pacify the island. To commit this country now to the recognition of any particular government in Cuba might subject us to embarrassing conditions of international obligation toward the organization so recognized. In case of intervention our conduct would be subject to the approval or disapproval of such government. We would be required to submit to its direction and to assume to it the mere relation of a friendly ally.

When it shall appear hereafter that there is within the island a government capable of performing the duties and discharging the functions of a separate nation, and having, as a matter of fact, the proper forms and attributes of nationality, such government can be promptly and readily recognized and the relations and interests of the United States with such nation adjusted.

There remain the alternative forms of intervention to end the war, either as an impartial neutral by imposing a rational compromise between the contestants, or as the active ally of the one party or the other.

As to the first it is not to be forgotten that during the last few months the relations of the United States has virtually been one of friendly intervention in many ways, each not of itself conclusive, but all tending to the exertion of a potential influence toward an ultimate pacific result, just and honorable to all interests concerned. The spirit of all our acts hitherto has been an earnest, unselfish desire for peace and prosperity in Cuba, untarnished by differences between us and Spain, and unstained by the blood of American citizens.

The forcible intervention of the United States as a neutral to stop the war, according to the large dictates of humanity and following many historical precedents where neighboring states have interfered to check the hopeless sacrifices of life by internecine conflicts beyond their borders, is justifiable on rational grounds. It involves, however, hostile constraint upon both the parties to the contest as well to enforce a truce as to guide the eventual settlement.

The grounds for such intervention may be briefly summarized as follows:

First. In the cause of humanity and to put an end to the barbarities, bloodshed, starvation, and horrible miseries now existing there, and which the parties to the conflict are either unable or unwilling to stop or mitigate. It is no answer to say this is all in another country, belonging to another nation, and is therefore none of our business. It is specially our duty, for it is right at our door.

Second. We owe it to our citizens in Cuba to afford them that protection and indemnity for life and property which no government there can or will afford, and to that end to terminate the conditions that deprive them of legal protection.

Third. The right to intervene may be justified by the very serious injury to the commerce, trade, and business of our people, and by the wanton destruction of property and devastation of the island.

Fourth, and which is of the utmost importance. The present condition of affairs in Cuba is a constant menace to our peace, and entails upon this government an enormous expense. With such a conflict waged for years in an island so near us and with which our people have such trade and business relations; when the lives and liberty of our citizens are in constant danger and their property destroyed and themselves ruined; where our trading vessels are liable to seizure and are seized at our very door by war ships of a foreign nation, the expeditions of filibustering11 that we are powerless to prevent altogether, and the irritating questions and entanglements thus arising—all these and others that I need not mention, with the resulting strained relations, are constant menace to our peace, and compel us to keep on a semiwar footing with a nation with which we are at peace.

These elements of danger and disorder already pointed out have been strikingly illustrated by a tragic event which has deeply and justly moved the American people. I have already transmitted to Congress the report of the naval court of inquiry on the destruction of the battleship Maine in the harbor of Havana during the night of the 15th of February. The destruction of that noble vessel has filled the national heart with inexpressible horror. Two hundred and fifty-eight brave sailors and marines and two officers of our Navy, reposing in the fancied security of a friendly harbor, have been hurled to death, grief and want brought to their homes, and sorrow to the nation.

The naval court of inquiry, which it is needless to say, commands the unqualified confidence of the government, was unanimous in its conclusion that the destruction of the Maine was caused by an exterior explosion, that of a submarine mine. It did not assume to place the responsibility. That remains to be fixed.

In any event the destruction of the Maine, by whatever exterior cause, is a patent and impressive proof of a state of things in Cuba that is intolerable. That condition is thus shown to be such that the Spanish government cannot assure safety and security to a vessel of the American Navy in the harbor of Havana on a mission of peace, and rightfully there. . . .

President Grant, in 1875, after discussing the phases of the contest as it then appeared, and its hopeless and apparent indefinite prolongation, said Each party seems quite capable of working great injury and damage to the other, as well as to all the relations and interests dependent on the existence of peace in the island; but they seem incapable of reaching any adjustment, and both have thus far failed of achieving any success whereby one party shall possess and control the island to the exclusion of the other. Under these circumstances, the agency of others, either by mediation or intervention, seems to be the only alternative which must sooner or later be invoked for the termination of the strife. . . .

The long trail has proved that the object for which Spain has waged the war cannot be attained. The fire of insurrection may flame or may smolder with varying seasons, but it has not been and it is plain that it cannot be extinguished by present methods. The only hope of relief and repose from a condition which can no longer be endured is the enforced pacification of Cuba. In the name of humanity, in the name of civilization, in behalf of endangered American interests which gives us the right and the duty to speak and to act, the war in Cuba must stop.

In view of these facts and of these considerations, I ask the Congress to authorize and empower the president to take measure to secure a full and final termination of hostilities between the government of Spain and the people of Cuba, and to secure in the island the establishment of a stable government, capable of maintaining order and observing its international obligations, insuring peace and tranquility and the security of its citizens as well as our own, and to use the military and naval forces of the United States as may be necessary for these purposes.

And in the interest of humanity and to aid in preserving the lives of the starving people of the island I recommend that the distribution of food and supplies be continued, and that an appropriation be made out of the public Treasury to supplement the charity of our citizens.

The issue is now with the Congress. It is a solemn responsibility. I have exhausted every effort to relieve the intolerable condition of affairs which is at our doors. Prepared to execute every obligation imposed upon me by the Constitution and the law, I await your action. . . .

. . .[This issue] will, I am sure, have your just and careful attention in the solemn deliberations upon which you are about to enter. If this measure attains a successful result, then our aspirations as a Christian, peace-loving people will be realized. If it fails, it will be only another justification for our contemplated action.

- 1. Article II, section 3.

- 2. See Monroe Doctrine and The Olney Corollary.

- 3. A practice implemented in 1896 to remove the Cuban population from areas in the countryside where rebel forces roamed at will. The “reconcentration” program forced thousands of Cubans into concentration camps. Two years later, an estimated one-third of Cuba’s population had been moved into these camps, where disease and malnutrition were commonplace.

- 4. Vicinity.

- 5. Antonio Cánovas del Castillo (1828–1897) was prime minister of Spain several times between 1875 and his assassination in 1897.

- 6. Stewart L. Woodford (1835–1913), Civil War brigadier general, lieutenant governor of New York, U.S. representative from New York, and the American ambassador to Spain 1897–98

- 7. Cubans sent to concentration camps.

- 8. A truce that took effect in 1878 ending, for a time, a Cuban independence movement that began in 1868.

- 9. Of the month before.

- 10. Parliament of Cuba.

- 11. Private efforts in support of foreign movements to secure independence, overthrow a foreign government, or other such revolutionary acts. While these private operations are generally undertaken without government approval, they sometimes provided cover for government-sponsored operations.

Annual Message to Congress (1898)

December 05, 1898

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.