No related resources

Introduction

Walter Rauschenbusch (1861–1918) was a theologian, Baptist minister, and activist associated with the Social Gospel, a progressive and primarily Protestant movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The movement advocated wide-reaching reform to ameliorate contemporary social, political, and economic problems—especially those associated with the ill effects of industrialization and urbanization—as a practical application of Christian morality. The movement sought to employ politics and administration to help perfect society and to realize God’s heavenly kingdom on earth. In his influential 1907 book, Christianity and the Social Crisis, Rauschenbusch argued that, rightly understood, Christian teaching had always been directed toward this utopian goal. The Church had failed in this duty, he claimed, but true Christianity might be reestablished by engaging the contemporary social and economic crisis presented by industry and urbanization.

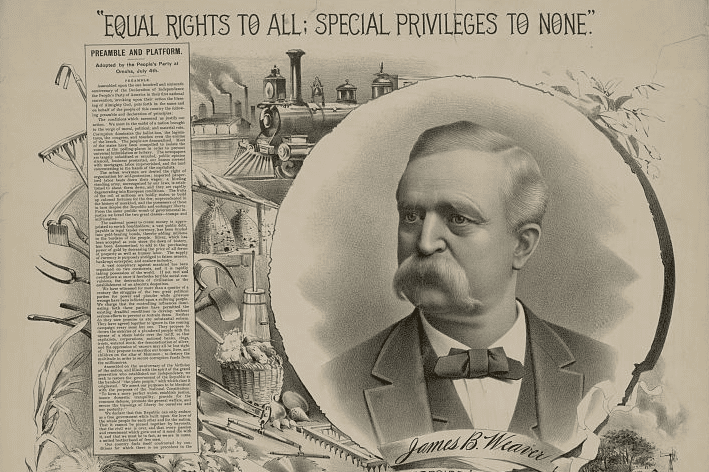

The redistribution of wealth; the socialization of property; and public ownership of railroads, mines, communications, and other goods were key elements in Rauschenbusch’s iteration of the Social Gospel. In the excerpt below, Rauschenbusch discussed the progressives’ demand for greater economic equality in America. He criticized the resistance to progressive economic reforms, which he saw as coming largely from wealthy special interests who unduly influenced the political process. Like many progressives of his day, Rauschenbusch argued that the rule of law and the inherent conservatism of courts were especially protective of these entrenched special interests.

Source: Walter Rauschenbusch, Christianity and the Social Crisis (New York: Macmillan, 1907), 247–86, available online at the Hathi Trust Digital Library: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044010386498&view=1up&seq=9. We have omitted the author’s original footnotes.

Approximate equality is the only enduring foundation of political democracy. The sense of equality is the only basis for Christian morality. Healthful human relations seem to run only on horizontal lines. Consequently true love always seeks to create a level. If a rich man loves a poor girl, he lifts her to financial and social equality with himself. If his love has not that equalizing power, it is flawed and becomes prostitution. Wherever husbands by social custom regard their wives as inferior, there is a deep-seated defect in married life. If a teacher talks down at his pupils, not as a maturer friend but with an “I say so,” he confines their minds in a spiritual straitjacket instead of liberating them. Equality is the only basis for true educational influences. Even our instinct of pity, which is love going out to the weak, works with spontaneous strength only toward those of our own class and circle who have dropped into misfortune. Businessmen feel very differently toward the widow of a businessman left in poverty than they do toward a widow of the poorer classes. People of a lower class who demand our help are “cases”; people of our own class are folks.

The demand for equality is often ridiculed as if it implied that all men were to be of identical wealth, wisdom, and authority. But social equality can coexist with the greatest natural differences. There is no more fundamental difference than that of sex, nor a greater intellectual chasm than that between an educated man and his little child, yet in the family all are equal. In a college community there are various gradations of rank and authority within the faculty, and there is a clearly marked distinction between the students and the faculty, but there is social equality. On the other hand, the janitor and the peanut vender are outside of the circle, however important they may be to it.

The social equality existing in our country in the past has been one of the chief charms of life here and of far more practical importance to our democracy than the universal ballot. After a long period of study abroad in my youth I realized on my return to America that life here was far poorer in music, art, and many forms of enjoyment than life on the continent of Europe; but that life tasted better here, nevertheless, because men met one another more simply, frankly, and wholesomely. In Europe a man is always considering just how much deference he must show to those in ranks above him, and in turn noting jealously if those below him are strewing the right quantity of incense due to his own social position.

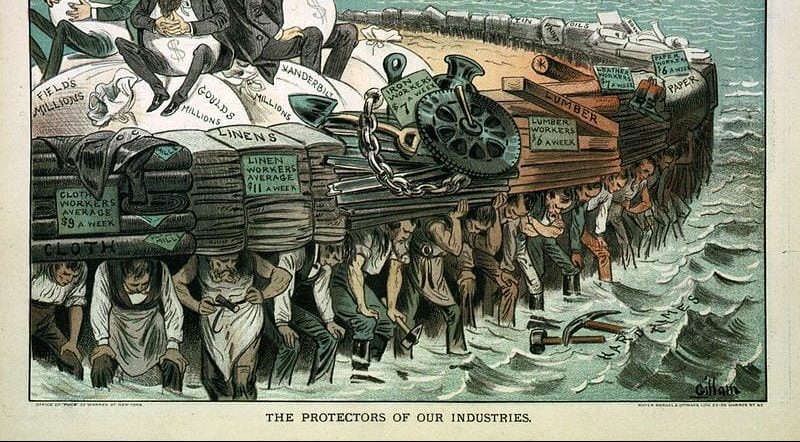

That fundamental democracy of social intercourse, which is one of the richest endowments of our American life, is slipping from us. Actual inequality endangers the sense of equality. The rich man and the poor man can meet on a level if they are old friends, or if they are men of exceptional moral qualities, or if they meet under unusual circumstances that reduce all things to their primitive human elements. But as a general thing they will live different lives, and the sense of unlikeness will affect all their dealings. With women the spirit of social caste seems to be even more fatally easy than with men. It may be denied that the poor in our country are getting poorer, but it cannot well be denied that the rich are getting richer. The extremes of wealth and poverty are much farther apart than formerly, and thus the poor are at least relatively poorer. There is a rich class and a poor class, whose manner of life is wedged farther and farther apart, and whose boundary lines are becoming ever more distinct. The difference in housing, eating, dressing, and speaking would be a sufficient barrier. The dominant position of the one class in industry and the dependence of the other is even more decisive. The owners or managers of industry are rich or highly paid; they have technical knowledge, the will to command, the habits of mind bred by the exercise of authority; they say “Go,” and men go; they say “Do this,” and an army of men obeys. On the other side is the mass who take orders, who are employed or dismissed at a word, who use their muscles almost automatically, and who have no voice in the conduct of their own shop. These are two distinct classes, and no rhetoric can make them equal. Moreover, such a condition is inseparable from the capitalistic organization of industry. As capitalism grows, it must create a proletariat to correspond. Just as militarism is based on military obedience, so capitalism is based on economic dependence.

We hear passionate protests against the use of the hateful word “class” in America. There are no classes in our country, we are told. But the hateful part is not the word, but the thing. If class distinctions are growing up here, he serves his country ill who would hush up the fact or blind the people to it by fine phrases. A class is a body of men who are so similar in their work, their duties and privileges, their manner of life and enjoyment, that a common interest, common conception of life, and common moral ideals are developed and cement the individuals. The businessmen constitute such a class. The industrial workers also constitute such a class. In old countries the upper class gradually adorned itself with titles, won special privileges in court and army and law, and created an atmosphere of awe and apartness. But the solid basis on which this was done was the feudal control of the land, which was then the great source of wealth. The rest was merely the decorative moss that grows up on the rocks of permanent wealth. With the Industrial Revolution a new source of wealth opened up; a new set of men gained control of it and ousted the old feudal nobility more or less thoroughly. The new aristocracy, which is based on mobile capital, has not yet had time to festoon itself with decorations, but likes to hasten the process by intermarriage with the remnants of the old feudal nobility. Whether it will ever duplicate the old forms in this country is immaterial, as long as it has the fact of power. In some way the social inequality will find increasing outward expression and will tend to make itself permanent. Where there are actual class differences, there will be a dawning class consciousness, a clear class interest, and there may be a class struggle. . . .

Individual sympathy and understanding have been our chief reliance in the past for overcoming the differences between the social classes. The feelings and principles implanted by Christianity have been a powerful aid in that direction. But if this sympathy diminishes by the widening of the social chasm, what hope have we? It is true that we have an increasing number who, by study and by personal contact in settlement work and otherwise, are trying to increase that sympathetic intelligence.[1] But it is a question if this conscious effort of individuals is enough to offset the unconscious alienation created by the dominant facts of life which are wedging entire classes apart.

Facts and institutions are inevitably followed by theories to explain and justify the existing institutions. In a political democracy we have democratic theories of politics. In a monarchy they have monarchical theories. Wherever inequality has been a permanent situation, theoretical thought has defended it. Aristotle living in a slaveholding society said: “There are in the human species individuals as inferior to others as the body is to the soul, or as animals are to men. Adapted to corporeal labor only, they are incapable of a higher occupation. Destined by nature to slavery, there is nothing better for them to do than to obey.”[2] Similarly in feudal society the lord regarded the serf as by nature little different from a beast of burden, and even the serf regarded oppression as a fixed fact in life, like cold and rain. If we allow deep and permanent inequality to grow up in our country, it is as sure as gravitation that not only the old democracy and frankness of manners will go, but even the theory of human equality, which has been part of our spiritual atmosphere through Christianity, will be denied. It is already widely challenged.

Any shifting of the economic equilibrium from one class to another is sure to be followed by a shifting of the political equilibrium. If a class arrives at economic wealth, it will gain political influence and some form of representation. For instance, when the cities grew powerful at the close of the Middle Ages, and the lesser nobles declined in power, that fact was registered in the political constitution of the nations. The French Revolution was the demand of the business class to have a share in political power proportionate to its growing economic importance. A class which is economically strong will have the necessary influence to secure and enforce laws which protect its economic interests. In turn, a class which controls legislation will shape it for its own enrichment. Politics is embroidered with patriotic sentiment and phrases, but at bottom, consciously or unconsciously, the economic interests dominate it always. If therefore we have a class which owns a large part of the national wealth and controls nearly all the mobile part of it, it is idle to suppose that this class will not see to it that the vast power exerted by the machinery of government serves its interests. And if we have another class which is economically dependent and helpless, it is idle to suppose that it will be allowed an equal voice in swaying political power. In short, we cannot join economic inequality and political equality. As Oliver Cromwell wrote to Parliament, “If there be any one that makes many poor to make a few rich, that suits not a Commonwealth.”[3] The words of Lincoln find a new application here, that the Republic cannot be half slave and half free.[4]

The power of capitalism over the machinery of our government, and its corroding influence on the morality of our public servants, has been revealed within recent years to such an extent that it is almost superfluous to speak of it. . . . There is probably not one of our states which is not more or less controlled by its chief railways. How far our national government is constantly warped in its action, the man at a distance can hardly tell, but the public

confidence in Congress is deeply undermined. . . .

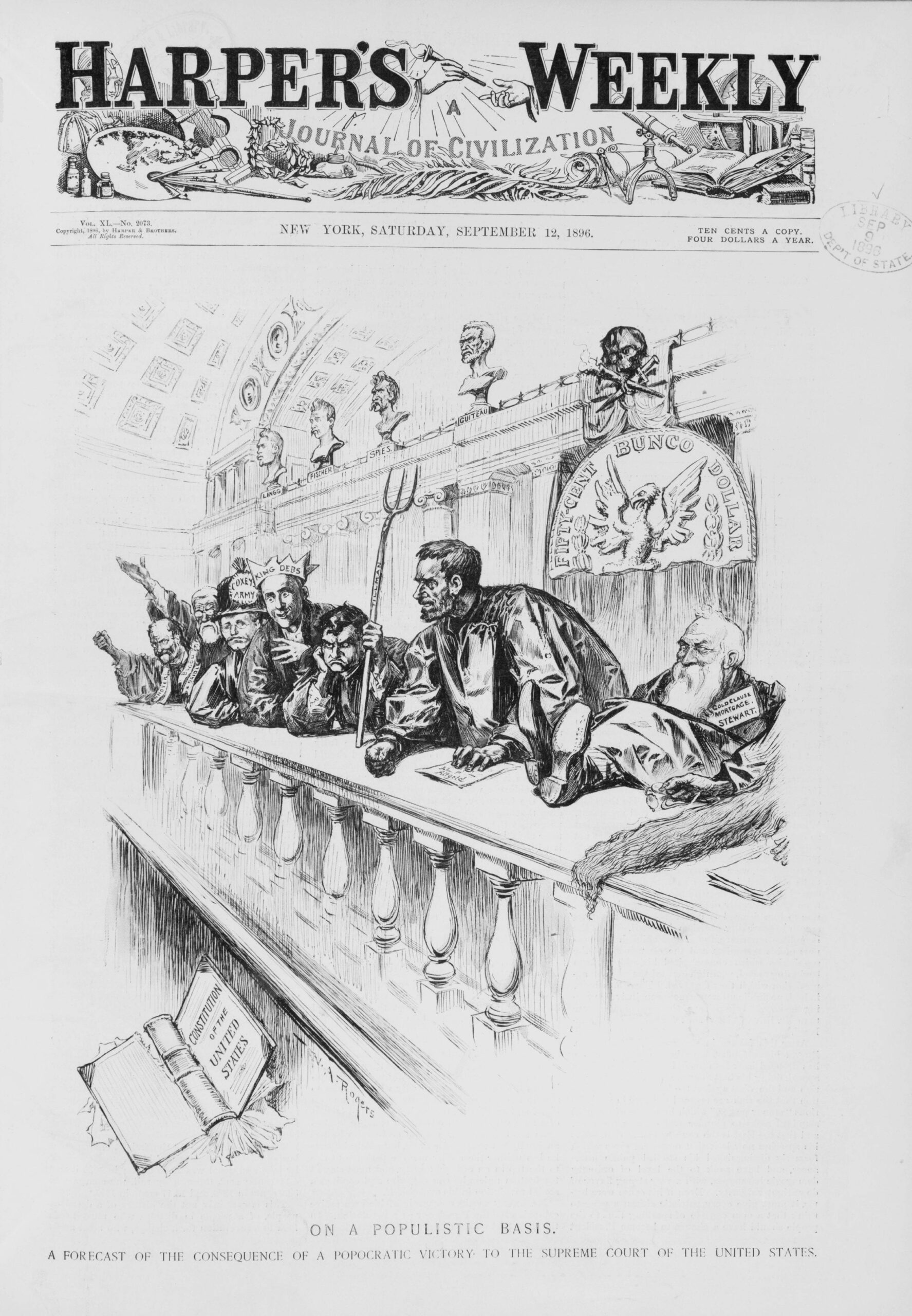

The courts are the instrument by which the organized community exercises its supremacy over the affairs of the individual, and the control of the courts is therefore of vital concern to the privileged classes of any nation. . . . In our own country all are equal before the law in theory. In practice there is the most serious inequality. The right of appeal as handled in our country gives tremendous odds to those who have financial staying power. . . .

To what extent the judges are actually corrupt it is probably impossible to say. We have been trying to keep up our courage amid the general official corruption by asserting that the integrity of the judiciary at least is above reproach. But the only thing that would make them immune to the general disease is the spirit and the tradition of their profession. But class spirit and professional honor are a rather fragile barrier against the terrible temptations which can be offered by the great interests, and when that barrier is once undermined by evil example, it will wash away with increasing speed. . . . [I]t is safe to say that the study and practice of the law create an ingrained respect for things as they have been, and that the social sympathies of judges are altogether likely to be with the educated and possessing classes. . . . Unless a judge is affected by the new social spirit, he is likely to be at least unconsciously on the side of those who have, and this is equivalent to a special privilege granted them by the courts. . . .

The ultimate power on which we stake our hope in our present political decay is the power of public opinion. Whenever some temporary victory has been scored by the people, the newspapers triumphantly announce that the people are really still sovereign, and that nothing can resist public opinion when once aroused. In reality this sheet anchor of our hope is as dependable as the wind that blows. It takes strenuous efforts to arouse the public. Only spectacular evils are likely to impress it. When it is aroused, it is easily turned against some side issue or some harmless scapegoat. And, like all passions, it is very short-lived and sinks back to slumber quickly. Despotic governments have always trusted in dilatory tactics, knowing well the somnolence of public opinion. The same policy is adroitly used by those who exploit the people in our country. To this must be added the fact that the predatory interests are tampering with the organs which create public opinion. If public opinion is indeed so great a power, it is not likely that it will be overlooked by those who are so alert against all other sources of danger. It will not be denied that some newspapers are directly in the pay of certain interests and are their active champions. . . . [T]he justice and efficiency of democratic government depend on the intelligence and information of the citizens. If they are purposely misled by distorted information or by the suppression of important information, the larger jury before which all public causes have to be pleaded is tampered with, and the innermost life of our republic is in danger.

. . . We have, in fact, one kind of constitution on paper, and another system of government in fact. That is usually the way when a slow revolution is taking place in the distribution of political and economic power. The old structure apparently remains intact, but actually the seat of power has changed. . . .

. . . The ideal of our government was to distribute political rights and powers equally among the citizens. But a state of such actual inequality has grown up among the citizens that this ideal becomes unworkable. . . . If we want approximate political equality, we must have approximate economic equality. . . .

If it were proposed to invent some social system in which covetousness would be deliberately fostered and intensified in human nature, what system could be devised which would excel our own for this purpose? Competitive commerce exalts selfishness to the dignity of a moral principle. It pits men against one another in a gladiatorial game in which there is no mercy and in which 90 percent of the combatants finally strew the arena. . . .

Industry and commerce are good. They serve the needs of men. The men eminent in industry and commerce are good men, with the fine qualities of human nature. But the organization of industry and commerce is such that along with its useful service it carries death, physical and moral. . . . Every joint-stock company, trust, or labor union organized, every extension of government interference or government ownership, is a surrender of the competitive principle and a halting step toward cooperation. Practical men take these steps because competition has proved itself suicidal to economic welfare. Christian men have a stouter reason for turning against it, because it slays human character and denies human brotherhood. If money dominates, the ideal cannot dominate. If we serve mammon, we cannot serve the Christ. . . .

Nations do not die by wealth, but by injustice. The forward impetus comes through some great historical opportunity which stimulates the production of wealth, breaks up the caked and rigid order of the past, sets free the energies of new classes, calls creative leaders to the front, quickens the intellectual life, intensifies the sense of duty and the ideal devotion to the common weal, and awakens in the strong individuals the large ambition of patriotic service. Progress slackens when a single class appropriates the social results of the common labor, fortifies its evil rights by unfair laws, throttles the masses by political centralization and suppression, and consumes in luxury what it has taken in covetousness. Then there is a gradual loss of productive energy, an increasing bitterness and distrust, a waning sense of duty and devotion to country, a paralysis of the moral springs of noble action. Men no longer love the Commonwealth, because it does not stand for the common wealth. Force has to supply the cohesive power which love fails to furnish. Exploitation creates poverty, and poverty is followed by physical degeneration. Education, art, wealth, and culture may continue to advance and may even ripen to their mellowest perfection when the worm of death is already at the heart of the nation. Internal convulsions or external catastrophes will finally reveal the state of decay. . . .

In the last resort the only hope is in the moral forces which can be summoned to the rescue. If there are statesmen, prophets, and apostles who set truth and justice above selfish advancement; if their call finds a response in the great body of the people; if a new tide of religious faith and moral enthusiasm creates new standards of duty and a new capacity for self-sacrifice; if the strong learn to direct their love of power to the uplifting of the people and see the highest self-assertion in self-sacrifice—then the entrenchments of vested wrong will melt away; the stifled energy of the people will leap forward; the atrophied members of the social body will be filled with a fresh flow of blood; and a regenerate nation will look with the eyes of youth across the fields of the future.

The cry of “Crisis! crisis!” has become a weariness. Every age and every year are critical and fraught with destiny. Yet in the widest survey of history Western civilization is now at a decisive point in its development.

Will some Gibbon of Mongol race sit by the shore of the Pacific in the year A.D. 3000 and write on the “Decline and Fall of the Christian Empire”?[5] If so, he will probably describe the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as the golden age when outwardly life flourished as never before, but when the decay, which resulted in a gradual collapse of the twenty-first and twenty-second centuries, was already far advanced.

Or will the twentieth century mark for the future historian the real adolescence of humanity, the great emancipation from barbarism and from the paralysis of injustice, and the beginning of a progress in the intellectual, social, and moral life of mankind to which all past history has no parallel?

It will depend almost wholly on the moral forces which the Christian nations can bring to the fighting line against wrong, and the fighting energy of those moral forces will again depend on the degree to which they are inspired by religious faith and enthusiasm. It is either a revival of social religion or the deluge.

- 1. On settlements, see “The Subjective Necessity for Social Settlements” in this volume.

- 2. Aristotle, Politics 1254b16–21.

- 3. Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658) was a military leader and politician during the English civil wars.. He eventually became Lord Protector of England and served as such until his death in 1658. For the source of Rauschenbusch’s quotation, see Cromwell’s dispatch to Parliament following the victory at Dunbar (September 4, 1650).

- 4. See Abraham Lincoln’s “House Divided” speech, Springfield, Illinois (June 16, 1858).

- 5. Rauschenbusch alludes to English historian Edward Gibbon’s famed multivolume study, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (published 1776–88).

Constitutional Government in the United States

December 31, 1908

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.