Introduction

Frank Goodnow (1859–1939), an American legal scholar and political scientist educated at Columbia University, was influential in the development of the academic dimension of the progressive movement. An eventual president of Johns Hopkins University and first president of the American Political Science Association, he is perhaps best known as an early innovator in the professional study of public administration and administrative law. In the following lecture, delivered at Brown University in 1916, Goodnow criticized the natural rights principles and social contract theory that informed the American founding. Goodnow’s argument was representative of progressives’ common claim that governments are not founded to secure some prepolitical notion of liberty that places theoretical and moral limitations on those governments. Rather, Goodnow argues that liberty is an evolving concept, subject to changing historical and economic conditions, and ultimately given meaning by government itself. Of particular note is Goodnow’s claim that American courts articulated and defended the “substantive rights” of individuals. According to Goodnow, the English legal tradition of “procedural” rights emphasized formal rules and legal protections such as trial by jury. Substantive rights, on the other hand, are rights to fundamental goods independent of mere procedure, such as the rights to life, liberty, and property. Substantive rights, many progressives claimed, took on an unduly absolutist and abstract character. Goodnow argued that American courts sometimes used such rights—especially freedom of contract and the right to private property—to protect wealthy special interests against progressive economic and labor legislation.

Source: Frank Johnson Goodnow, The American Conception of Liberty and Government (Providence, RI: Standard, 1916), 7–31, available online at the Hathi Trust Digital Library: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.$b21989;view=1up;seq=7.

The end of the eighteenth century was marked by the formulation and general acceptance by thinking men in Europe of a political philosophy which laid great emphasis on individual private rights. Man was by this philosophy conceived of as endowed at the time of his birth with certain inalienable rights. Thus, Rousseau in his “Social Contract” treated man as primarily an individual and only secondarily as a member of human society.[1] Society itself was regarded as based upon a contract made between the individuals by whose union it was formed. At the time of making this contract these individuals were deemed to have reserved certain rights spoken of as “natural” rights. These rights could neither be taken away nor be limited without the consent of the individual affected.

Such a theory, of course, had no historical justification. There was no record of the making of any such contract as was postulated. It was impossible to assert, as a matter of fact even, that man existed first as an individual and that later he became, as the result of any act of volition on his part, a member of human society. But at a time when truth was sought usually through speculation rather than observation, the absence of proof of the facts which lay at the basis of the theory did not seriously trouble those by whom it was formulated or accepted.

While there was no justification in fact for this social contract theory and this doctrine of natural rights, their acceptance by thinking men did nevertheless have an important influence upon the development of thought and in that way upon the actual conditions of human life. For these theories were not only a philosophical explanation of the organization of society; they were at the same time the result of the then existing social conditions, and like most such theories were also an attempt to justify a course of conduct which was believed to be expedient.

At the end of the eighteenth century a great change was beginning in Western Europe. The enlargement of the field of commercial transactions, due to the discovery and colonization of America and to the contact of Europe with Asia, particularly with India, had opened new spheres of activity to those minded for adventure. The invention of the steam engine and its application to manufacturing were rapidly changing industrial conditions. The factory system was in process of establishment and had already begun to displace domestic industry.

The new possibilities of reward for individual endeavor made men impatient of the restrictions on private initiative incident to an industrial and commercial system which was fast passing away. They therefore welcomed with eagerness a political philosophy which, owing to the emphasis it placed upon private rights, would if acted upon have the effect of freeing them from what they regarded as hampering limitations on individual initiative.

This political philosophy was incorporated into the celebrated Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen promulgated in France on the eve of the Revolution. A perusal of this remarkable document reveals the fact, however, that the reformers of France had not altogether emancipated themselves from the influences of their historical development. For almost every clause of the Declaration refers to rights under the law rather than to rights which were natural to and inherent in man.[2]

The subsequent development in Europe of this private rights philosophy is along the lines thus marked out by the Declaration. The rights which men have been recognized as possessing have not been considered to be inherent rights, attaching to man at the time of his birth, so much as rights which find their origin in the law as adopted by that organ of government regarded as representative of the society of which the individual man is a member.

In a word, man is regarded now throughout Europe, contrary to the view expressed by Rousseau, as primarily a member of society and secondarily as an individual. The rights which he possesses are, it is believed, conferred upon him, not by his Creator, but rather by the society to which he belongs. What they are is to be determined by the legislative authority in view of the needs of that society. Social expediency, rather than natural right, is thus to determine the sphere of individual freedom of action.

The development of this private rights philosophy has been, however, somewhat different in the United States. The philosophy of Rousseau was accepted in this country probably with even greater enthusiasm than was the case in Europe. The social and economic conditions of the Western world were, in the first place, more favorable than in Europe for its acceptance. There was at the time no well-developed social organization in this country. America was the land of the pioneer, who had to rely for most of his success upon his strong right arm. Such communities as did exist were loosely organized and separated one from another. Roads worthy of the name hardly existed and communication was possible only by rivers which were imperfectly navigable or over a sea which, when account is taken of the vessels then in use, was tempestuous in character.

Furthermore, the religious and moral influences in this country, which owed much to the Protestant Reformation, all favored the development of an extreme individualism. They emphasized personal responsibility and the salvation of the individual soul. It was the fate of the individual rather than that of the social group which appealed to the preacher or aroused the anxiety of the theologian. It was individual rather than social morality which was emphasized by the ethical teacher and received attention in moral codes. Everything, in a word, favored the acceptance of the theory of individual natural rights.

The result was the adoption in this country of a doctrine of unadulterated individualism. Every one had rights. Social duties were hardly recognized, or if recognized little emphasis was laid upon them. It was apparently thought that every one was able and willing to protect his rights, and that as a result of the struggle between men for their rights and of the compromise of what appeared to be conflicting rights would arise an effective social organization.

The rights with which it was believed that man was endowed by his Creator were, as was the case in France, set forth in bills of rights which formed an important part of American constitutions. The form in which they were stated in American bills of rights was subject to fewer qualifications than was the case in France. Their origin was found in nature rather than in the law. The development of these rights, further, has been quite different from the European development which has been noted. American courts, early in the history of the country, claimed and secured the general recognition of a power to declare unconstitutional and therefore void acts of legislation which, in their opinion, were not in conformity with these bills of rights. In their determination of these questions, American courts appear to have been largely influenced by the private rights conception of the prevalent political philosophy. The result has been that the private individual rights of American citizens have come to be formulated and defined, not by representative legislative bodies, as is now the rule in Europe, but by courts which have in the past been much under the influence of the political philosophy of the eighteenth century.

In thus adopting the continental political philosophy of the eighteenth century, American judges modified greatly the conception of individual liberty which was the basis of English political practice. The most important modifications were two in number:

In the first place, the rights of men, of which their liberty consisted, were, as natural rights, regarded in a measure—and in no small measure—as independent of the law. This modification of the original English idea was an almost necessary result of the fact that these rights were set forth in written constitutions, which were placed under the protection of courts. The written constitution was considered to be the act of the sovereign people. It therefore was superior to any mere laws which might be passed by the representatives of the people in the lawmaking bodies. These bodies being simply delegates of the people were not authorized to do anything not within the powers granted to them. If a written constitution provided that a man had a certain right, it was evident that the legislature could not take it away from him. When the courts assumed in the United States the power to declare unconstitutional acts of the legislature, they did so because their duty was to apply the law as they found it. They might not, therefore, apply as law an act of the legislature which in their opinion was in conflict with the Constitution, since, being in conflict with the Constitution, the highest law of all, such an act could not be law.

In this way natural rights came to have an existence apart from the law, or, at any rate, apart from the law as it had up to that time been understood.

The importance which was attributed by the Americans of those days to this idea of natural rather than legal rights will be appreciated when we recall that the Constitution of the United States, which in its original form contained few if any provisions relative to these natural rights, was ultimately adopted only on condition that they should be enumerated in a bill of rights to be appended to the Constitution. This was subsequently done in Amendments I to IX. The Ninth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in particular is a characteristic expression of the feeling of the time that these natural rights existed independently of all law. It reads: “The enumeration in the Constitution of certain rights shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.”

In the second place, our American courts emphasized substantive rights rather than the right to particular methods of procedure. Most of the historic rights of Englishmen had been rights to particular methods of action. Thus, the right to a special kind of trial for crime—that is, the right to trial by jury—was regarded as one of the most sacred rights of an Englishman.

The English insistence on particular methods of procedure was due to the belief that these methods had shown themselves, as the result of a long experience, to be valuable aids in securing the end desired. This end was freedom from arbitrary autocratic action on the part of those to whom political power had been entrusted. It was the rule of law—that is, the rule of a principle of general application as opposed to the rule of a person arbitrary and capricious—which the Englishman sought. It was to secure his rights through this rule of law that he originated the form of government which has been called “constitutional.” The Englishman, as a matter of fact, never claimed that he had any natural rights; that is, rights to which he was entitled by reason of the fact that he is a man, a human being. He was perfectly satisfied if it was recognized in his political and legal system that no attempt might be made, except in the manner by law provided, to take away what he might think were his rights. This claim being admitted, he felt that in some way or other he would be able to have the law so formulated that he could secure the recognition of all substantive rights which he ought at any particular time to possess. To secure the recognition in the law of these substantive rights he insisted upon the grant to more and more of the people of the land of the power to control legislation. For through the control of legislation was obtained the power to determine what are his rights.

The rights of Englishmen were, therefore, so far as they were defined at all, to be found in acts of legislation and in judicial decisions. . . .

The power of the American courts to determine in the concrete and in detail . . . the content of private rights was very large because of the fact that these rights were often stated in very general terms in the Constitution. The most marked instance of such vagueness is perhaps to be found in the almost universal provision that no one shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. The Constitution does not define property nor liberty nor due process of law. All these matters have had to be “pricked out,” as Mr. Justice Holmes of the U.S. Supreme Court has said in decisions which are almost too numerous to be counted.[3]

The following are some of the conclusions characteristic of American ideas of private rights which the courts have reached:

The clause providing that private property shall not be taken for public use without just compensation has been interpreted as prohibiting inferentially the taking of property for private use.[4] The interpretation is really due to the recognition in the individual of a natural inherent substantive right of property which may be taken from him by the government only in the case mentioned in the Constitution, viz., by taking property for public use. . . .

. . . [T]he clause providing that no person shall “be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law” has been held by some of the state courts, under the influence of the idea of inherent absolute individual substantive rights to prevent the legislature from passing an act which changes the basis of the liability of employer to employed.[5] The old basis of the liability was negligence. The act declared unconstitutional provided in the case of accident a liability on the part of the employer regardless of the question whether he was negligent or not. Other acts of legislation have been declared unconstitutional as violating this due process clause, because they imposed upon an employer the duty to pay employees in money, or at stated periods, or because they forbade an employer to work his men more than a certain number of hours a week or a day. These acts were held unconstitutional as depriving either the employer or the employed of his property or his liberty.

Such decisions have been reached as a result of the fact that the American courts have emphasized the idea of a substantive right and have lost sight of the fact that the right granted in the Constitution if defined in the light of its history was a right not under all conceivable circumstances to liberty or property, but merely a right not to be deprived of liberty or property except in a certain way, that is, by due process of law. The fact that in all these cases an act of the legislature, that is, a law in the historic English sense, provided that liberty or property should be taken away was not regarded by the courts as due process of law. In fact the courts of the United States have really taken the position that there is no due process of law by which the individual may be deprived of some of these absolute substantive inherent natural rights.

Furthermore and partly as a consequence of the acceptance of the conception of private rights as inherent and not based upon law, the content and character of private rights specifically provided for by legislation have been fixed, not so much as the result of an inquiry into their social expediency but rather because it has been believed that the individual has rights with which he has been endowed by his Creator, rights which it would be improper to take away or to limit even in the interest of society. . . .

This general attitude toward private rights is, it seems to me, at the present time in process of modification. Whatever may have been formerly the advantages attaching to a private rights political philosophy—and that they were many I should be the last person to deny—this question of private rights has been reexamined with the idea of ascertaining whether, under the conditions of modern life, our traditional political philosophy should be retained.

The political philosophy of the eighteenth century was formulated before the announcement and acceptance of the theory of evolutionary development. The natural rights doctrine presupposed almost that society was static or stationary rather than dynamic or progressive in character. It was generally believed at the end of the eighteenth century that there was a social state which under all conditions and at all times would be absolutely ideal. The rights which man had were believed to come from his Creator. These rights consequently were the same then as they once had been and would always remain the same. Natural rights were in theory thus permanent and immutable. Natural rights being conceived of as eternal and immutable, the theory of natural rights did not permit of their amendment in view of a change in conditions.

The actual rights which at the close of the eighteenth century were recognized were, however, as a matter of fact influenced in large measure by the social and economic conditions of the time when the recognition was made. Those conditions have certainly been subjected to great modifications. The pioneer can no longer rely upon himself alone. Indeed with the increase of population and the conquest of the wilderness the pioneer has almost disappeared. The improvement in the means of communication, which has been one of the most marked changes that have occurred, has placed in close contact and relationship once separated and unrelated communities. The canal and the railway, the steamship and the locomotive, the telegraph and the telephone, we might add the motor car and the airplane, have all contributed to the formation of a social organization such as our forefathers never saw in their wildest dreams. The accumulation of capital, the concentration of industry with the accompanying increase in the size of the industrial unit and the loss of personal relations between employer and employed, have all brought about a constitution of society very different from that which was to be found a century and a quarter ago. Changed conditions, it has been thought, must bring in their train different conceptions of private rights if society is to be advantageously carried on. In other words, while insistence on individual rights may have been of great advantage at a time when the social organization was not highly developed, it may become a menace when social rather than individual efficiency is the necessary prerequisite of progress. For social efficiency probably owes more to the common realization of social duties than to the general insistence on privileges based on individual private rights. As our conditions have changed . . . the attitude of our courts on the one hand toward private rights and on the other hand toward social duties has gradually been changing. The general theory remains the same. Man is still said to be possessed of inherent natural rights of which he may not be deprived without his consent. The courts still now and then hold unconstitutional acts of legislature which appear to encroach upon those rights. At the same time the sphere of governmental action is continually widening and the actual content of individual private rights is being increasingly narrowed.

- 1. Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) of Geneva was a political philosopher influential in the development of social contract theory, wherein legitimate civil society, generally, is thought to result from an agreement made among individuals in order to secure their natural rights. See his 1762 treatise, On the Social Contract; or Principles of Political Rights.

- 2. Passed by the National Constituent Assembly during the French Revolution, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen appealed to the abstract “natural, unalienable, and sacred rights of man” (e.g., the rights to “liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression”). However, many of the rights listed in the document refer to the particular rights of citizens as such (e.g., criminal protections, property, speech, press, and conscience protections).

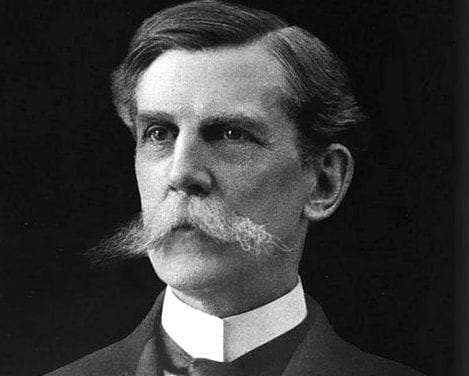

- 3. Progressive legal scholar and U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. (1841–1935). A prominent expert on the common law, Holmes was a leading proponent of “legal realism,” a method of constitutional interpretation that privileges experience and enacted law over abstract theory. As such, Holmes criticized the idea that natural rights and natural law are reliable guides for jurisprudence. See his influential essay, “Natural Law” (1918).

- 4. See the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

- 5. See the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

The Zimmermann Telegram

January 11, 1917

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.