No related resources

Introduction

When the Spanish-American War ended in 1898, the United States had to decide what rights the people in the newly acquired territories were to possess. Up to then, the U.S. government considered territories to have the complete protection of the Constitution and a clear, straightforward path to statehood. But did this model fit Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam, which were not considered future states because of their distance, their racial composition, or both? The preliminary answer came from a series of Supreme Court rulings now known as the Insular Cases. The most notable case was Downes v. Bidwell, decided in 1901. The case specifically concerned a merchant, Samuel Downes, whose company had imported oranges into the port of New York from Puerto Rico and had been forced to pay import duties on them. He sued George R. Bidwell, U.S. customs inspector for the port of New York. Because the duties would not have been charged if the oranges had been imported from another state, Downes argued that the tax violated Article I, section 8 of the Constitution, which requires that “all duties, imposts, and excises shall be uniform throughout the United States.”

This seemingly mundane business matter raised a much more significant question: Did the Constitution follow the flag? By a vote of five to four, the Supreme Court decided that it did not when it came to revenue and administrative issues. In those instances, territories like Puerto Rico were not subject to the Constitution, only to the power of Congress. The Court insisted, however, that with regard to fundamental rights the Constitution did follow the flag.

Justice John Marshall Harlan (1833–1911), in dissent, held that Congress was always bound to enact laws, including those for territories, within the authority of the Constitution, and that it was inimical to republican government to think that the Congress could act outside that. Therefore, the Constitution applied in its full power to Puerto Rico, and Congress could not impose any duty, impost, or excise that departed from the rule of uniformity established by the Constitution.

Source: Downes v. Bidwell, 182 U.S. 244 (1901), available at https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/182/244/. We have removed in-text references to laws and court decisions. All footnotes provided by the editors.

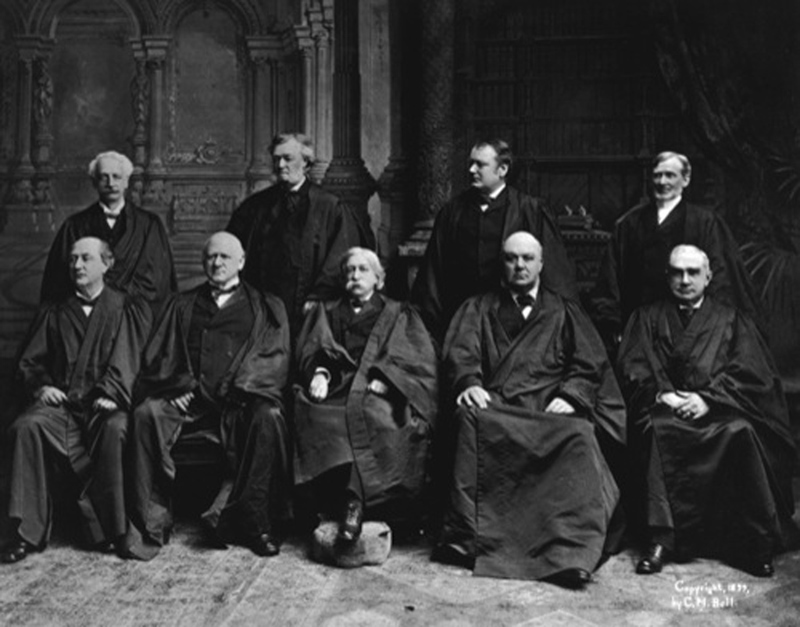

. . . Mr. Justice Brown,[1] . . . announced the conclusion and judgment of the Court.

This case involves the question whether merchandise brought into the port of New York from Puerto Rico since the passage of the Foraker Act[2] is exempt from duty. . . .

. . . The liberality of Congress in legislating the Constitution into all our contiguous territories has undoubtedly fostered the impression that it went there by its own force, but there is nothing in the Constitution itself, and little in the interpretation put upon it, to confirm that impression. . . . The Executive and Legislative departments of the government have for more than a century interpreted this silence as precluding the idea that the Constitution attached to these territories as soon as acquired, and unless such interpretation be manifestly contrary to the letter or spirit of the Constitution, it should be followed by the judicial department.

Patriotic and intelligent men may differ widely as to the desireableness of this or that acquisition, but this is solely a political question. We can only consider this aspect of the case so far as to say that no construction of the Constitution should be adopted which would prevent Congress from considering each case upon its merits, unless the language of the instrument imperatively demand it. A false step at this time might be fatal to the development of what Chief Justice Marshall called the American empire. Choice in some cases, the natural gravitation of small bodies toward large ones in others, the result of a successful war in still others, may bring about conditions which would render the annexation of distant possessions desirable. If those possessions are inhabited by alien races, differing from us in religion, customs, laws, methods of taxation, and modes of thought, the administration of government and justice according to Anglo-Saxon principles may for a time be impossible, and the question at once arises whether large concessions ought not to be made for a time, that ultimately our own theories may be carried out and the blessings of a free government under the Constitution extended to them. We decline to hold that there is anything in the Constitution to forbid such action.

We are therefore of opinion that the Island of Puerto Rico is a territory appurtenant and belonging to the United States, but not a part of the United States within the revenue clauses of the Constitution; that the Foraker Act is constitutional, so far as it imposes duties upon imports from such island, and that the plaintiff cannot recover back the duties exacted in this case. . . .

Mr. Justice White, concurring with Mr. Justice Shiras and Mr. Justice McKenna, in the affirmative.

. . . It is a general rule of public law, recognized and acted upon by the United States, that whenever political jurisdiction and legislative power over any territory are transferred from one nation or sovereign to another the municipal laws of the country—that is, laws which are intended for the protection of private rights—continue in force until abrogated or changed by the new government or sovereign. By the cession, public property passes from one government to the other, but private property remains as before, and with it those municipal laws which are designed to secure its peaceful use and enjoyment. As a matter of course, all laws, ordinances, and regulations in conflict with the political character, institutions, and constitution of the new government are at once displaced. Thus, upon a cession of political jurisdiction and legislative power—and the latter is involved in the former—to the United States, the laws of the country in support of an established religion, or abridging the freedom of the press, or authorizing cruel and unusual punishments, and the like, would at once cease to be of obligatory force, without any declaration to that effect; and the laws of the country on other subjects would necessarily be superseded by existing laws of the new government upon the same matters. But with respect to other laws affecting the possession, use, and transfer of property, and designed to secure good order and peace in the community, and promote its health and prosperity, which are strictly of a municipal character, the rule is general that a change of government leaves them in force until, by direct action of the new government, they are altered or repealed.[3]

There is in reason, then, no room in this case to contend that Congress can destroy the liberties of the people of Puerto Rico by exercising in their regard powers against freedom and justice which the Constitution has absolutely denied. There can also be no controversy as to the right of Congress to locally govern the island of Puerto Rico as its wisdom may decide, and in so doing to accord only such degree of representative government as may be determined on by that body. There can also be no contention as to the authority of Congress to levy such local taxes in Puerto Rico as it may choose, even although the amount of the local burden so levied be manifold more onerous than is the duty with which this case is concerned. But as the duty in question was not a local tax, since it was levied in the United States on goods coming from Puerto Rico, it follows that, if that island was a part of the United States, the duty was repugnant to the Constitution, since the authority to levy an impost duty[4] conferred by the Constitution on Congress does not, as I have conceded, include the right to lay such a burden on goods coming from one to another part of the United States. And, besides, if Puerto Rico was a part of the United States the exaction was repugnant to the uniformity clause.

The sole and only issue, then, is not whether Congress has taxed Puerto Rico without representation,—for, whether the tax was local or national, it could have been imposed although Puerto Rico had no representative local government and was not represented in Congress,—but is whether the particular tax in question was levied in such form as to cause it to be repugnant to the Constitution. This is to be resolved by answering the inquiry, had Puerto Rico, at the time of the passage of the act in question [the Foraker Act], been incorporated into and become an integral part of the United States? . . .

. . . The demonstration which it seems to me is afforded by the review which has preceded [a review of treaties of annexation and laws related to annexation] is, besides, sustained by various other acts of the government which to me are wholly inexplicable except upon the theory that it was admitted that the government of the United States had the power to acquire and hold territory without immediately incorporating it. . . . In concluding my appreciation of the history of the government [with regard to annexation], attention is called to the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which to my mind seems to be conclusive. The first section of the amendment, the italics being mine, reads as follows: “Sec. 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” Obviously this provision recognized that there may be places subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, but which are not incorporated into it, and hence are not within the United States in the completest sense of those words. . . .

It is, then, as I think, indubitably settled by the principles of the law of nations, by the nature of the government created under the Constitution, by the express and implied powers conferred upon that government by the Constitution, by the mode in which those powers have been executed from the beginning, and by an unbroken line of decisions of this Court, first announced by Marshall and followed and lucidly expounded by Taney, that the treaty-making power cannot incorporate territory into the United States without the express or implied assent of Congress, that it may insert in a treaty conditions against immediate incorporation, and that, on the other hand, when it has expressed in the treaty the conditions favorable to incorporation, they will, if the treaty be not repudiated by Congress, have the force of the law of the land, and therefore by the fulfillment of such conditions cause incorporation to result. It must follow, therefore, that, where a treaty contains no conditions for incorporation, and, above all, where it not only has no such conditions, but expressly provides to the contrary, that incorporation does not arise until, in the wisdom of Congress, it is deemed that the acquired territory has reached that state where it is proper that it should enter into and form a part of the American family.

[Justice White here considers whether the treaty with Spain giving Puerto Rico to the United States incorporated the island into the United States or required incorporation, and concludes it did not.]

The result of what has been said is that, while in an international sense Puerto Rico was not a foreign country, since it was subject to the sovereignty of and was owned by the United States, it was foreign to the United States in a domestic sense, because the island had not been incorporated into the United States, but was merely appurtenant thereto as a possession. As a necessary consequence, the impost in question assessed on coming from Puerto Rico into the United States after the cession was within the power of Congress, and that body was not, moreover, as to such impost, controlled by the clause requiring that imposts should be uniform throughout the United States—in other words, the provision of the Constitution just referred to was not applicable to Congress in legislating for Puerto Rico. . . .

Mr. Justice Harlan, dissenting:

I concur in the dissenting opinion of the Chief Justice.[5] The grounds upon which he and Mr. Justice Brewer and Mr. Justice Peckham regard the Foraker Act as unconstitutional in the particulars involved in this action meet my entire approval. Those grounds need not be restated, nor is it necessary to reexamine the authorities cited by the Chief Justice. I agree in holding that Puerto Rico—at least after the ratification of the treaty with Spain—became a part of the United States within the meaning of the section of the Constitution enumerating the powers of Congress, and providing the “all duties, imposts, and excises shall be uniform throughout the United States.” . . .

Although from the foundation of the government this court has held steadily to the view that the government of the United States was one of enumerated powers, and that no one of its branches, nor all of its branches combined, could constitutionally exercise powers not granted, or which were not necessarily implied from those expressly granted we are now informed that Congress possesses powers outside of the Constitution, and may deal with new territory, acquired by treaty or conquest, in the same manner as other nations have been accustomed to act with respect to territories acquired by them. In my opinion, Congress has no existence and can exercise no authority outside of the Constitution. Still less is it true that Congress can deal with new territories just as other nations have done or may do with their new territories. This nation is under the control of a written constitution, the supreme law of the land and the only source of the powers which our government, or any branch or officer of it, may exert at any time or at any place. Monarchical and despotic governments, unrestrained by written constitutions, may do with newly acquired territories what this government may not do consistently with our fundamental law. To say otherwise is to concede that Congress may, by action taken outside of the Constitution, engraft upon our republican institutions a colonial system such as exists under monarchical governments. Surely such a result was never contemplated by the fathers of the Constitution. If that instrument had contained a word suggesting the possibility of a result of that character it would never have been adopted by the people of the United States. The idea that this country may acquire territories anywhere upon the earth, by conquest or treaty, and hold them as mere colonies or provinces—the people inhabiting them to enjoy only such rights as Congress chooses to accord to them—is wholly inconsistent with the spirit and genius, as well as with the words, of the Constitution.

The idea prevails with some—indeed, it found expression in arguments at the bar—that we have in this country substantially or practically two national governments; one to be maintained under the Constitution, with all its restrictions; the other to be maintained by Congress outside and independently of that instrument, by exercising such powers as other nations of the earth are accustomed to exercise. It is one thing to give such a latitudinarian construction to the Constitution as will bring the exercise of power by Congress, upon a particular occasion or upon a particular subject, within its provisions. It is quite a different thing to say that Congress may, if it so elects, proceed outside of the Constitution. The glory of our American system of government is that it was created by a written constitution which protects the people against the exercise of arbitrary, unlimited power, and the limits of which instrument may not be passed by the government it created, or by any branch of it, or even by the people who ordained it, except by amendment or change of its provisions. “To what purpose,” Chief Justice Marshall said in Marbury v. Madison, “are powers limited, and to what purpose is that limitation committed to writing, if these limits may, at any time, be passed by those intended to be restrained? The distinction between a government with limited and unlimited powers is abolished if those limits do not confine the persons on whom they are imposed, and if acts prohibited and acts allowed are of equal obligation.”[6]

The wise men who framed the Constitution, and the patriotic people who adopted it, were unwilling to depend for their safety upon what, in the opinion referred to, is described as “certain principles of natural justice inherent in Anglo-Saxon character, which need no expression in constitutions or statutes to give them effect or to secure dependencies against legislation manifestly hostile to their real interests.”[7] They proceeded upon the theory—the wisdom of which experience has vindicated—that the only safe guaranty against governmental oppression was to withhold or restrict the power to oppress. They well remembered that Anglo-Saxons across the ocean had attempted, in defiance of law and justice, to trample upon the rights of Anglo-Saxons on this continent, and had sought, by military force, to establish a government that could at will destroy the privileges that inhere in liberty. They believed that the establishment here of a government that could administer public affairs according to its will, unrestrained by any fundamental law and without regard to the inherent rights of freemen, would be ruinous to the liberties of the people by exposing them to the oppressions of arbitrary power. Hence, the Constitution enumerates the powers which Congress and the other departments may exercise—leaving unimpaired, to the states or the People, the powers not delegated to the national government nor prohibited to the states. That instrument so expressly declares in the 10th Article of Amendment.[8] It will be an evil day for American liberty if the theory of a government outside of the supreme law of the land finds lodgment in our constitutional jurisprudence. No higher duty rests upon this court than to exert its full authority to prevent all violation of the principles of the Constitution. . . .

In the opinion to which I have referred it is suggested that conditions may arise when the annexation of distant possessions may be desirable. “If,” says that opinion,[9] “those possessions are inhabited by alien races, differing from us in religion, customs, laws, methods of taxation, and modes of thought, the administration of government and justice, according to Anglo-Saxon principles, may for a time be impossible; and the question at once arises whether large concessions ought not to be made for a time, that ultimately our own theories may be carried out, and the blessings of a free government under the Constitution extended to them. We decline to hold that there is anything in the Constitution to forbid such action.” In my judgment, the Constitution does not sustain any such theory of our governmental system. Whether a particular race will or will not assimilate with our people, and whether they can or cannot with safety to our institutions be brought within the operation of the Constitution, is a matter to be thought of when it is proposed to acquire their territory by treaty. A mistake in the acquisition of territory, although such acquisition seemed at the time to be necessary, cannot be made the ground for violating the Constitution or refusing to give full effect to its provisions. The Constitution is not to be obeyed or disobeyed as the circumstances of a particular crisis in our history may suggest the one or the other course to be pursued. The People have decreed that it shall be the supreme law of the land at all times. When the acquisition of territory becomes complete, by cession, the Constitution necessarily becomes the supreme law of such new territory, and no power exists in any department of the government to make “concessions” that are inconsistent with its provisions. . . .

We heard much in argument[10] about the “expanding future of our country.” It was said that the United States is to become what is called a “world power”; and that if this government intends to keep abreast of the times and be equal to the great destiny that awaits the American people, it must be allowed to exert all the power that other nations are accustomed to exercise. My answer is, that the fathers never intended that the authority and influence of this nation should be exerted otherwise than in accordance with the Constitution. If our government needs more power than is conferred upon it by the Constitution, that instrument provides the mode in which it may be amended and additional power thereby obtained. The people of the United States who ordained the Constitution never supposed that a change could be made in our system of government by mere judicial interpretation. They never contemplated any such juggling with the words of the Constitution as would authorize the courts to hold that the words “throughout the United States,” in the taxing clause of the Constitution, do not embrace a domestic “territory of the United States” having a civil government established by the authority of the United States. This is a distinction which I am unable to make, and which I do not think ought to be made when we are endeavoring to ascertain the meaning of a great instrument of government. . . .

In my opinion Puerto Rico became, at least after the ratification of the treaty with Spain, a part of and subject to the jurisdiction of the United States in respect of all its territory and people, and that Congress could not thereafter impose any duty, impost, or excise with respect to that island and its inhabitants, which departed from the rule of uniformity established by the Constitution.

- 1. Associate Justice Henry Billings Brown (1836–1913).

- 2. The Foraker Act (1900), officially known as the Organic Act of 1900, established civilian (albeit limited popular) government on Puerto Rico. It was sponsored by Ohio Senator Joseph B. Foraker (1846–1919). The new government had a governor and an eleven-member Executive Council appointed by the president of the United States, a House of Representatives with thirty-five elected members, a judicial system with a Supreme Court and a United States District Court, and a nonvoting resident commissioner in Congress. One of the sources of revenue for the territorial government was a duty imposed on Puerto Rican oranges imported into the United States.

- 3. Justice White quotes from the Supreme Court’s opinion in Chicago, Rock Island &c. Railway v. McGlinn (1885) 114 U.S. 542.

- 4. An impost is a tax.

- 5. Melville Weston Fuller (1833–1910).

- 6. John Marshall (1755–1835). Marshall’s ruling in Marbury v. Madison (1803) asserted the principle of judicial review, whereby courts could strike down federal and state laws if they conflicted with the Constitution.

- 7. Harlan is quoting here and below from the argument of Associate Justice Brown in the majority opinion of the Court in Downes v. Bidwell .See above.

- 8. Justice Harlan is referring to the Tenth Amendment to the Constitution.

- 9. Justice Brown’s opinion for the Court. See above.

- 10. Arguments made before the Court when it heard the case.

First Annual Message to Congress (1901)

December 03, 1901

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.