No related resources

Introduction

Thomas Brackett Reed (1839–1902) was Speaker of the House of Representatives from 1889–1891 and 1895–1899. He was an extremely powerful Speaker who was often referred to as “Czar Reed,” and he used the Speaker’s powers to establish firm party and majority control of the House of Representatives. His “Reed Rules” were the source of this power, and those rules severely limited the power of the minority to delay the course of House business. In these articles, Reed provided a public defense of his majoritarian philosophy of government and described how the rules of the House of Representatives should be modified to ensure majority control. The Constitution designed Congress to represent an extended sphere of territory, bringing in many different interests to prevent majority tyranny (see Federalist No. 10, but this could also lead to so much disagreement that nothing could be accomplished. In addition, committees had accumulated a great deal of power by 1890 (see Congressional Government, further fragmenting power and leading to gridlock. However, Reed argued, party leadership could make it easier for a majority to act in unison, if the rules and procedures of Congress gave the leaders sufficient authority. Reed’s vision for the House was one where party majorities, through strong leadership, could represent the will of the national majority when considering and enacting legislation.

Source: North American Review, vol. 149, Oct. 1889, and North American Review, vol. 152, Feb. 1891.

“Obstructions in the National House”

. . . In the House of Representatives the rules, like those of the House of Commons[1], were made upon the very proper hypothesis that every member could be relied upon to do his public duty; that he would vote when the question was up, and would conform to the spirit and intent of the rules, and not violate them both while keeping to the letter. A motion to adjourn, a motion to take a recess, and a motion to adjourn to a future day are all motions absolutely necessary for the transaction of public business. It is supposed that each member who makes such a motion makes it not only because he thinks the House ought so to act, but also because he thinks it probably will so act. Any other course is a violation of that understanding on which all rules must rest. And yet a member may make one of these motions, may, indeed, make all of them, and repeat the series again and again, without himself believing that either ought to be adopted, and without the slightest expectation that either will be adopted. In such a case, the member is simply availing himself of the forms of rules intended to facilitate business, for the sole purpose of obstructing business.

Again, whenever bills are presented to the House for reference to appropriate committees, any member can demand that a bill be read. This is an obvious right; for upon the contents depends the reference, and on that members may be called to vote. In making such a request, which is not usual, since in ordinary cases the bill is sure to go to a suitable committee, the member ought to be actuated by a desire to ascertain the contents of the bill in order that he may be prepared to vote intelligently on its reference if called upon. But it has many times happened that the member himself has introduced, for the purpose of demanding their reading, long and tedious bills in which he had no interest–bills already before Congress—in order that, by mere consumption of time by the reading clerk, the legislative day might be wasted on which two-thirds of the House would otherwise have voted to pass a bill which was obnoxious to this single member.

. . . What is a legislative body for? It is not merely to make laws. It is to decide on all questions of public grievance, to determine between the different views entertained by men of diverse interests, and to reconcile them both with justice. It must be in some form hear the people. A negative decision by a legislative body is of as much value to the community as a law. Time is not lost when cases are investigated and action refused. Half the grievances of mankind turn out to be unfounded as soon as somebody is found to listen to them. The law courts decide cases according to law already made, but there is a large class of cases too indefinite for general laws, or which have grown up since general laws were passed, which demand the attention of a body capable of making laws to suit cases. A legislature is the court of very last resort. Therefore it would seem as if it should have such rules of action as would make the majority efficient. Our government is founded upon the idea of majority rule. There can be no other government by the people.

. . . Among the fears that are sometimes entertained, whenever a proposition is made that wiser rules shall be adopted, is the fear lest precipitate action, soon to be repented of, will be taken. There was never any fear so groundless as that. The inertia of a legislative body of three hundred men is something enormous anywhere, but is greater, perhaps, in the House of Representatives than anywhere else. There are, and can be, no parliamentary bodies of large membership which can transact business expeditiously. With the greatest liberty new rules could possibly give to it, the House could never pass upon one-fifth of the business presented. With this fear of precipitate action goes the other fear that there would be less debate–less opportunity to present objections and discuss amendments. This fear also is without foundation. Indeed, one of the incentives now to the cutting-off of debate is the fear that it may be used by the unscrupulous in aid and furtherance of delay and dilatory motions. If dilatory motions were reduced to their lowest limit, or, even as such, entirely abolished, there would be greater facilities for action and consideration; and therefore, there would be a greater chance for debate, and the danger of unwise laws would be much lessened.

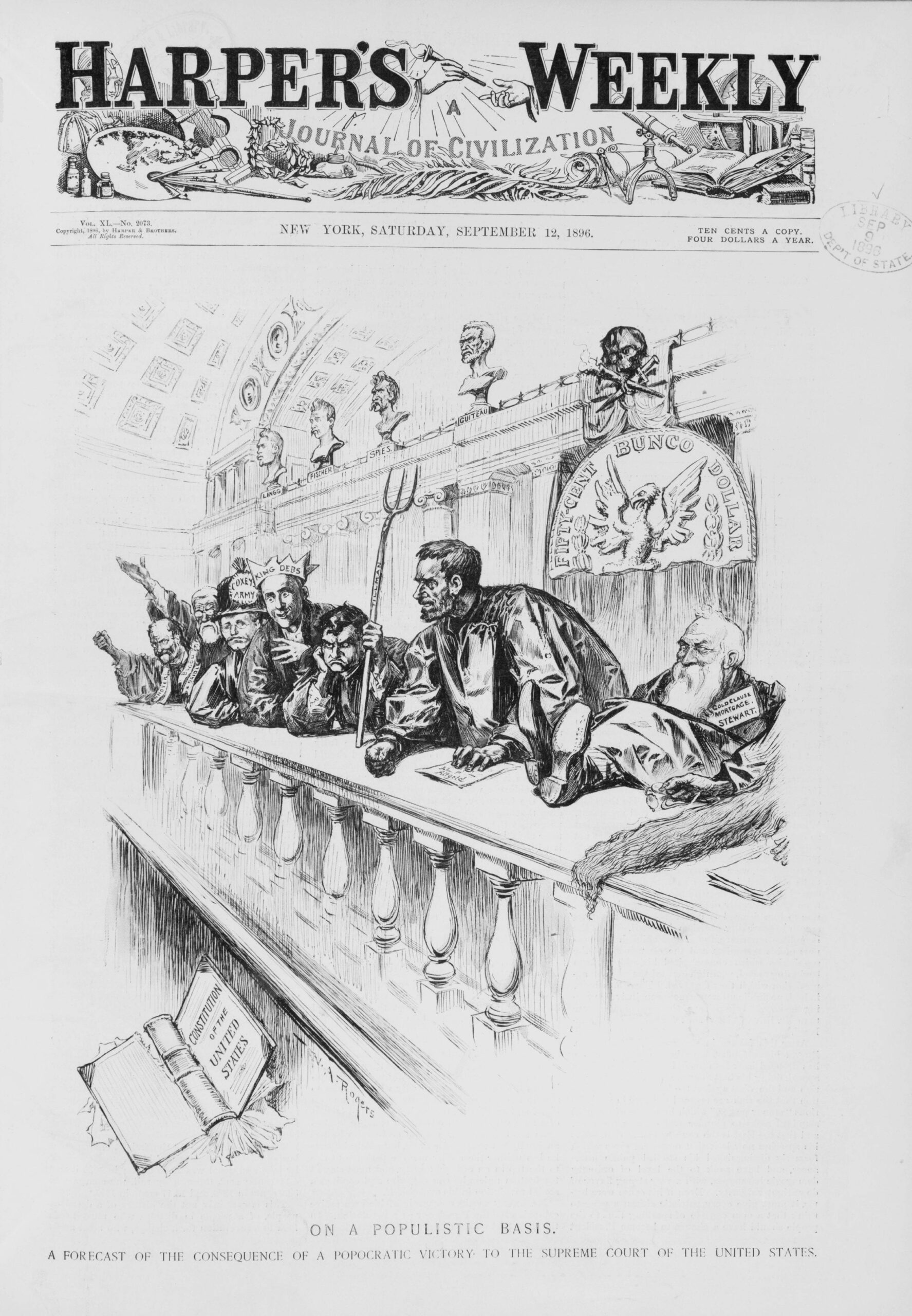

The present system is capable of indefinite abuse, and the actual abuse is increasing every year. For all the period preceding the year 1882, it was always a point of honor not to use dilatory motions in an election case. It being the duty of the House to determine the election of its own members, and its own character being determined by its membership, to prevent a decision upon a contested-election case seemed to undermine the very foundations of parliamentary government. But in 1882, taking advantage of the great confusion into which the death of Garfield[2] and the circumstances which followed had thrown their opponents, the Democrats refused to vote in an election case, and, when a quorum of Republicans was obtained, refused even to let them vote. This illegitimate warfare was carried on to the complete stoppage of all public business, until the House by a change of its rules, summarily took away the power of using dilatory motions in election cases, and thus put down the parliamentary rebellion. . . .

“A Deliberative Body”

. . . [The purpose of electing representatives to the House] seems in part so clear from text-books which speak of the Constitution, so clear from the tacit understanding of all mankind, that it seems almost like trifling to attempt to describe it. And yet there is so much confusion made in late discussions, so much declamation about the rights of minorities and freedom of speech, that a definition of the most valuable purpose of this mighty struggle [in House elections] seems really needful. So far as I can understand it, this struggle, battle, and decision have for their purpose, as regards the House of Representatives, the election of a representative body, which, so far as its powers go, is to formulate into laws the wishes of the people who are to be governed by these laws and who have expressed their wishes at the polls.

The making of laws is the main function of a legislative body. To that end all other things, however, important, are subordinate. When I say the making of laws, I mean to include the deliberate refusal to make them if deemed wiser; for it so happens that the negative determination against a new law is a positive determination to stand by the old existing laws. In order to make laws wisely the body must be a deliberative body; but deliberation, however necessary or valuable, is only the means to an end; and that end is the right decision whether to make a law or not, and what shape to put it into if made. Debating is useful in lawmaking, but is not in itself an end or aim. . . .

It seems to be assumed that deliberation and debate mean talk only. It seems to be supposed, if a man is talking to the four walls of a room empty of everything but himself, that he is debating. But that is not so. Debate and deliberation imply listeners. If, for instance,—a thing hardly to be contemplated even in a mere supposition,—every time a senator arose to speak every other senator left the room, the senator who arose might be talking words of wisdom, might even be making a great oration, but he would not be debating, and the Senate at that moment would not be a deliberative body. . . .

Debate as a guide to the understanding, debate as a modifier of opinions and an equalizer of wisdom, debate as an intellectual and moral aid to teach the voter how to vote and the legislator how to legislate, is as welcome to every man of sense as the rain on the thirsty soil or the shadow of a great rock in a weary land. But debate which meanders on through the dreary hours with oft-repeated platitudes, full of wise saws without even the flavor of a modern instance, solemn repetitions of stale arguments made with owlish solemnity to empty benches, and all with no purpose except to obstruct legislation and hinder the public business, is about as grateful to the soul as a simoon in the desert or the storm which drizzled over Sodom and Gomorrah.[3]

For what purpose is a House of Representatives elected? Is it to pass the appropriation bills and then go home and say to the people?—“You certainly ordered us by your votes to do certain things; you undoubtedly went through the agony of a fiercely-contested election and decided upon certain questions, and entrusted us with the making of the laws to carry out your decisions, but we have not done anything of the sort. We know that the only use of debate is to enable us to make laws properly, but we found the right of debate so sacred, the raiment of so much more value than the body, that we have let the men you beat at the polls beat us in the halls of legislation. You voted one way, and we regarded the rights of minorities as so sacred that we were forced to register your votes the other way. You voted one way; the result worked out by us was the other.” How in the world can men reconcile such an answer with all the struggle and stress of an election? If minorities have superior rights, what is the use of trying to be a majority? Why should orators convince the judgments and able editors to satisfy the minds of voters if nothing is to come of it? Why have an election if it chooses nothing? why a decision at the polls if it decides nothing?

If the doctrine that the minority is to rule be once established, then will come the natural sequence—How small can you make that minority and still rule? That way despotism lies, not Democracy. But the reader will ask, Why did not our forefathers restrict debate? why did they allow such unlimited discussion? The answer is that even they restricted it by the previous question, and that was all that was necessary in their time. Misuse of debate for obstruction only was so rare that it was much wiser to endure it than to suppress it. . . .

. . . Within the last fourteen years there has been such a growth of obstruction that remedies had to be found, and still others must be found in the future. Such remedies, while they will, after the unreasoning passions have subsided, lead to real debates and sound deliberation such as we all desire, will also utterly cut off mere talk, that moth of time and of business, which seeks to kill by indirection what nobody could kill in the open House by an open vote. . . .

Comparison is often made between the freedom of debate allowed in early times and the restrictions of the present day. A few considerations and a few facts and figures will put that comparison in a different light. It cannot be too often reiterated that obstruction as known in our days was utterly unknown in the earlier days. It is not meant by this statement to say that there were no cases of lawless action, and that men never struggled against the majority; for there are instances where great opposition was made. But it never became until during the last ten years a systematic, every-day action in certain kinds of cases. Debate was seldom made the means of delay. . . .

It may be true that the new House, which will enter upon its duties next December or sooner, may be misled into giving up its powers as a legislative body; but if it is, it cannot escape the consequences. It has been demonstrated that a House of Representatives or any other deliberative body of the United States can, by the exercise of its constitutional powers, keep all the pledges of a campaign and enact, so far as one body goes, all the laws which the people have ordained. Henceforth the reply of a party that it was hindered by a minority and could not act will never again be taken as answer or excuse.

- 1. The lower house of the British Parliament

- 2. President James A. Garfield (1831–1881) was fatally shot by Charles Guiteau, a disgruntled federal office-seeker, on July 2, 1881, less than four months after becoming president following the election of 1880. While Guiteau’s shot killed Garfield, he did not die until 79 days after the shooting. Garfield’s lengthy death caused tremendous confusion in the country, and particularly among Republicans, who were internally divided over issues of political patronage (the distribution of political offices to party supporters).

- 3. “Simoon” here probably refers to the strong winds typically of the Sahara and Arabian deserts. These hot, dry, dusty winds are typically called “simooms” today; Sodom and Gomorrah were cities in the Bible that were destroyed for their wicked ways when “the Lord rained down burning sulfur” upon them. See Genesis 19:24.

Annual Message to Congress (1889)

December 03, 1889

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.