No related resources

Introduction

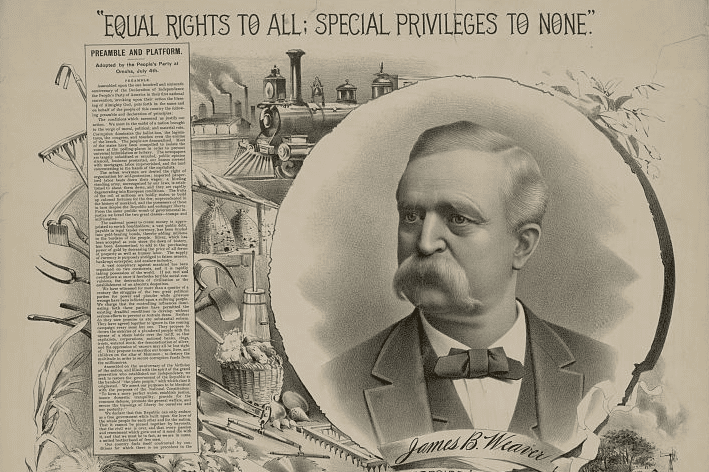

American expansionists had long desired to acquire the Hawaiian Islands to enhance the nation’s military and economic status. As early as 1842, President John Tyler noted that the islands were frequented by American ships and that the United States would be most dissatisfied “at any attempt by another power. . . to take possession of the islands.”

The dream of acquiring Hawaii came closer to becoming a reality during the administration of President Benjamin Harrison (1889–1893) when Secretary of State John W. Foster (the grandfather of both future CIA director Allen Dulles and future secretary of state John Foster Dulles) approved a clandestine operation to undermine the Hawaiian monarchy and acquire this strategic outpost in the Pacific Ocean.

The point man for this sensitive operation in Hawaii was the American ambassador, John Stevens. Foster made a point of not responding to some of Stevens’ more impolitic messages, although in some cases it appears Foster did respond but the documents were destroyed. As with previous operations of this sort, the American government went to great lengths to ensure that there was no embarrassing paper trail.

Ambassador Stevens promoted Hawaiian annexation throughout his tenure by repeatedly warning Washington that Great Britain had designs on the islands. Even at this late date in American history, the specter of British machinations tended to prompt an American reaction, or overreaction. On at least two occasions Stevens noted that potential unrest on the part of the native population would provide an opening for British intervention. The Washington Post supported this claim when it published excerpts of a leaked British confidential report discussing Pearl Harbor’s significance as a naval base.

American immigrants in Hawaii, including pineapple magnate Sanford Dole, the grandson of immigrants, had long been pushing for annexation. Ambassador Stevens spent much of his time trying to persuade two such annexation movements to settle their differences and present a united front. If these groups could coalesce, he told them, “they would carry all before them.” On January 17, 1893, these groups, rose in a “spontaneous” insurrection. During the revolt, Stevens ordered an American cruiser that happened to be offshore to dispatch a contingent of U.S. Marines to secure American lives and property. This action, in concert with Stevens’ immediate recognition of the provisional rebel government, led Queen Lili’uokalani to abdicate her throne.

Back in Washington, President Harrison congratulated Stevens for his decisive action and informed Congress that there was no U.S. government involvement in the events. Harrison ordered Stevens to use the Marine Corps contingent to maintain law and order and suppress any violence. When Grover Cleveland defeated Harrison in his bid for reelection in 1892, however, he withdrew the treaty of annexation from Senate consideration due to reports of American complicity with the insurrection.

Cleveland’s withdrawal only delayed the inevitable. President William McKinley and a Republican-controlled Congress formally annexed Hawaii in 1898. In 1993, on the 100th anniversary of the insurrection, the U.S. Senate apologized for the American government’s role in toppling the Hawaiian monarchy, prompting some critics of the apology to wonder if the nation had abandoned its historic opposition to monarchical rule.

The excerpts below are from telegrams exchanged between Foster and Stevens, along with a brief passage from Secretary Foster’s book published in 1904. For additional information on the annexation of Hawaii, see Westward Expansion, ed. Patrick J. Garrity and David Tucker (Ashbrook Press, 2020), Documents 11 and 33

Secretary of State Foster to John Stevens November 8, 1892, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1894, Appendix 2, Affairs In Hawaii, 376, available at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1894app2/pg_376; John Stevens to Secretary of State Foster, November 20, 1892, Message from the President of the United States, Transmitting Correspondence respecting Relations between the United States and the Hawaiian Islands from September 1820 to January 1893, February 17, 1893, 52nd Congress, 2nd session, Executive Document 77, 184-85, 188–89, 190–92, available at https://www.google.com/books/edition/Message_from_the_President_of_the_united/mTYqY0QuWS8C?hl=en&gbpv=0; Secretary of State Foster to John Stevens, January 28, 1893, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1894, Appendix 2, Affairs In Hawaii, 399, available at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1894app2/pg_399; John W. Foster, American Diplomacy in the Orient (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1903), 384–85, available at https://www.google.com/books/edition/American_Diplomacy_in_the_Orient/pYcXS8WIfz0C?hl=en&gbpv=0.

Secretary of State Foster to John Stevens, November 8, 1892

Sir: Adverting to your current dispatches in relation to the course of political events in the Hawaiian Islands, many of which are marked by you “confidential,” and for obvious reasons, I desire to suggest that you endeavor to separate your reports into two classes, one of which shall aim to give the narrative of public affairs in their open historical aspect, and the other to be of a strictly reserved and confidential character, reporting and commenting upon matters of personal intrigue and the like so far as you may deem necessary for my full understanding of the situation. Many of your dispatches combine these two modes of treatment to such a degree as to make their publication, in the event of a call from Congress or other occasion therefor, inexpedient, and, indeed, impracticable, without extended omissions. I am, etc., John W. Foster.

John Stevens to Secretary of State Foster, November 20, 1892

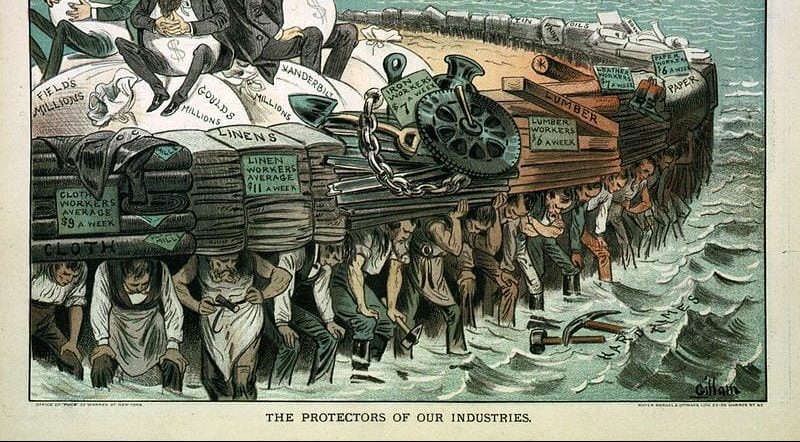

An intelligent and impartial examination of the facts can hardly fail to lead to the conclusion that the relations and policy of the United States toward Hawaii will soon demand some change, if not the adoption of decisive measures, with the aim to secure American interests and future supremacy by encouraging Hawaiian development and aiding to promote responsible government in these islands. It is unnecessary for me to allude to the deep interest and the settled policy of the U.S. government in respect of these islands, from the official days of John Quincy Adams and of Daniel Webster to the present time. In all that period, we have avowed the superiority of our interests to those of all other nations, and have always refused to embarrass our freedom of action by any alliance or arrangement with other powers as to the ultimate possession and government of the islands. Before stating the present political condition of the little kingdom, it is well to review the substantial data as to its area, its resources, its financial and business condition, its capabilities of material development, its population, the status of its landed property, its government, revenues, and expenditures, etc. . . .

he men qualified are here to carry on good government, provided they have the support of the government of the United States.1 Why not postpone American possession? Would it not be just as well for the United States to take the islands twenty-five years hence? Facts and obvious probabilities will answer both of these interrogations. Hawaii has reached the parting of the ways. She must now take the road which leads to Asia, or the other, which outlets her in America, gives her an American civilization, and binds her to the care of American destiny. The nonaction of the American government here in thirty years will make of Hawaii a Singapore, or a Hongkong, which could be governed as a British colony, but would be unfit to be an American territory or an American state under our constitutional system.2 If the American flag floats here at no distant day, the Asiatic tendencies can be arrested and controlled without retarding the material development of the islands, but surely advancing their prosperity by diversifying and expanding the industries, building roads and bridges, opening the public lands to small farmers from Europe and the United States, thus increasing the responsible voting population, and constituting a solid basis for American methods of government. . . .

One of two courses seem to me absolutely necessary to be followed, either bold and vigorous measures for annexation or a “customs union,” an ocean cable from the Californian coast to Honolulu, Pearl Harbor perpetually ceded to the United States, with an implied but not necessarily stipulated American protectorate over the islands. I believe the former to be the better, that which will prove much the more advantageous to the islands, and the cheapest and least embarrassing in the end for the United States. . . .

I cannot refrain from expressing the opinion with emphasis that the golden hour is near at hand. A perpetual customs union and the acquisition of Pearl Harbor, with an implied protectorate, must be regarded as the only allowable alternative. This would require the continual presence in the harbor of Honolulu of a U.S. vessel of war and the constant watchfulness of the U.S. minister while the present bungling, unsettled, and expensive political rule would go on, retarding the development of the islands, leaving at the end of twenty-five years more embarrassment to annexation than exists today, the property far less valuable, and the population less American than they would be if annexation were soon realized. . . .

Which of the two lines of policy and action shall be adopted our statesmen and our government must decide. Certain it is that the interests of the United States and the welfare of these islands will not permit the continuance of the existing state and tendency of things. Having for so many years extended a helping hand to the islands and encouraging the American residents and their friends at home to the extent we have, we cannot refrain now from aiding them with vigorous measures, without injury to ourselves and those of our “kith and kin,” and without neglecting American opportunities that never seemed so obvious and pressing as they do now. I have no doubt that the more thoroughly the bed rock and controlling facts touching the Hawaiian problem are understood by our government and by the American public, the more readily they will be inclined to approve the views I have expressed so inadequately in this communication.

I am, sir, your obedient servant,

John L. Stevens

Secretary of State Foster to John Stevens, January 28, 1893

Your dispatch, telegraphed from San Francisco, announcing revolution and establishment of a provisional government was received today. Your course in recognizing an unopposed de facto government appears to have been discreet and in accordance with the facts. The rule of this government has uniformly been to recognize and enter into relation with any actual government in full possession of effective power with the assent of the people. You will continue to recognize the new government under such conditions. It is trusted that the change, besides conducing to the tranquility and welfare of the Hawaiian Islands, will tend to draw closer the intimate ties of amity and common interests which so conspicuously and necessarily link them to the United States. You will keep in constant communication with the commander of the U.S. naval force at Honolulu, with a view to acting if need be for the protection of the interests and property of American citizens and aiding in the preservation of good order under the changed condition reported.

John W. Foster

John W. Foster, American Diplomacy in the Orient

he annexation of Hawaii to the United States was the necessary result of the policy announced by Secretary Webster in 1842, and steadily pursued by each succeeding administration. This result was foreseen by European statesmen such as Lord Palmerston, and by intelligent observers of the geographical situation of the islands in relation to the commerce of the Pacific. The reasons for it were doubly increased by the acquisition of the Philippine Islands. Hawaii then became more than an outpost of the territory of the American Union on the western coast of the continent. It was a link in the chain of its possessions in the Pacific. It would have been the excess of political unwisdom to allow this group of islands to fall into the hands of Great Britain or Japan, either of which powers stood ready to occupy them.

The native inhabitants [of Hawaii] had proved themselves incapable of maintaining a respectable and responsible government, and lacked the energy or the will to improve the advantages which Providence had given them in a fertile soil. They were fast dying out as a race, and their places were being occupied by sturdy laborers from China and Japan. There was presented to the American residents [on Hawaii] the same problem which confronted their contact with the aborigines of the Atlantic coast.

A government was established in Hawaii which had all the elements of a de jure and de facto sovereignty, and had vigorously maintained itself for four years. It sought for incorporation into the American Union. Under all the circumstances the president and Congress of the United States would have been recreant to their trust if they had failed to take advantage of the opportunity.

- 1. Stevens was probably referring to American settlers, many of whose families had been on the islands for decades.

- 2. American settlers on Hawaii were worried about the influx of Japanese agricultural laborers. Their presence on the islands increased the interest of the government of Japan in Hawaii, which concerned both the settlers and American officials.

Annual Message to Congress (1892)

December 06, 1892

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.