Introduction

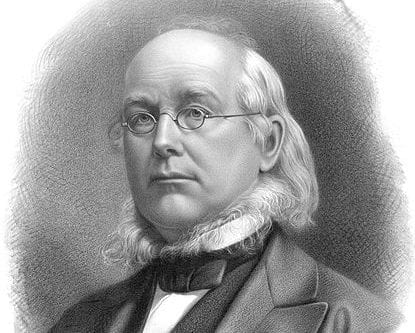

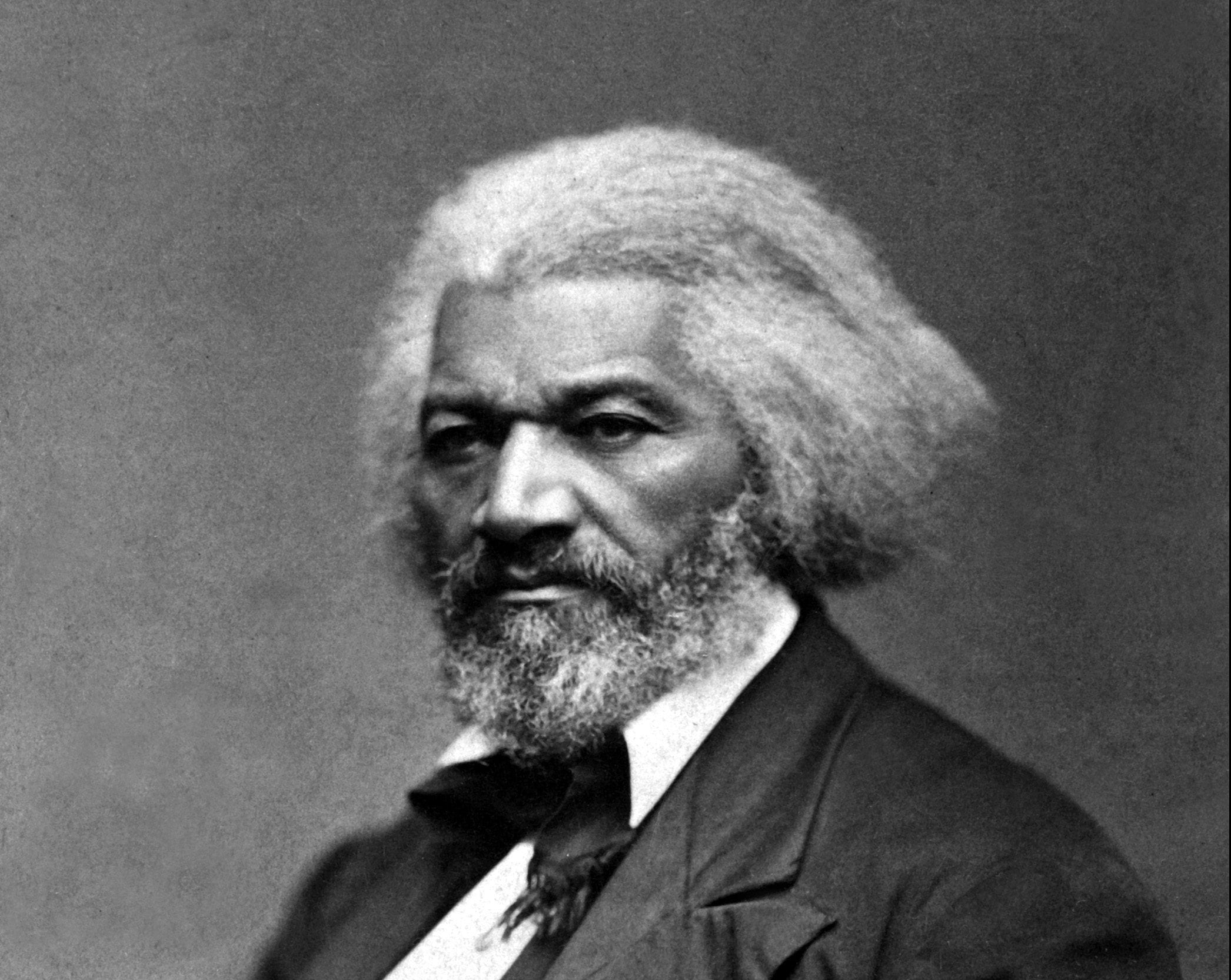

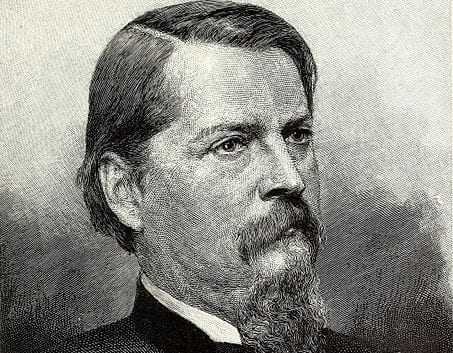

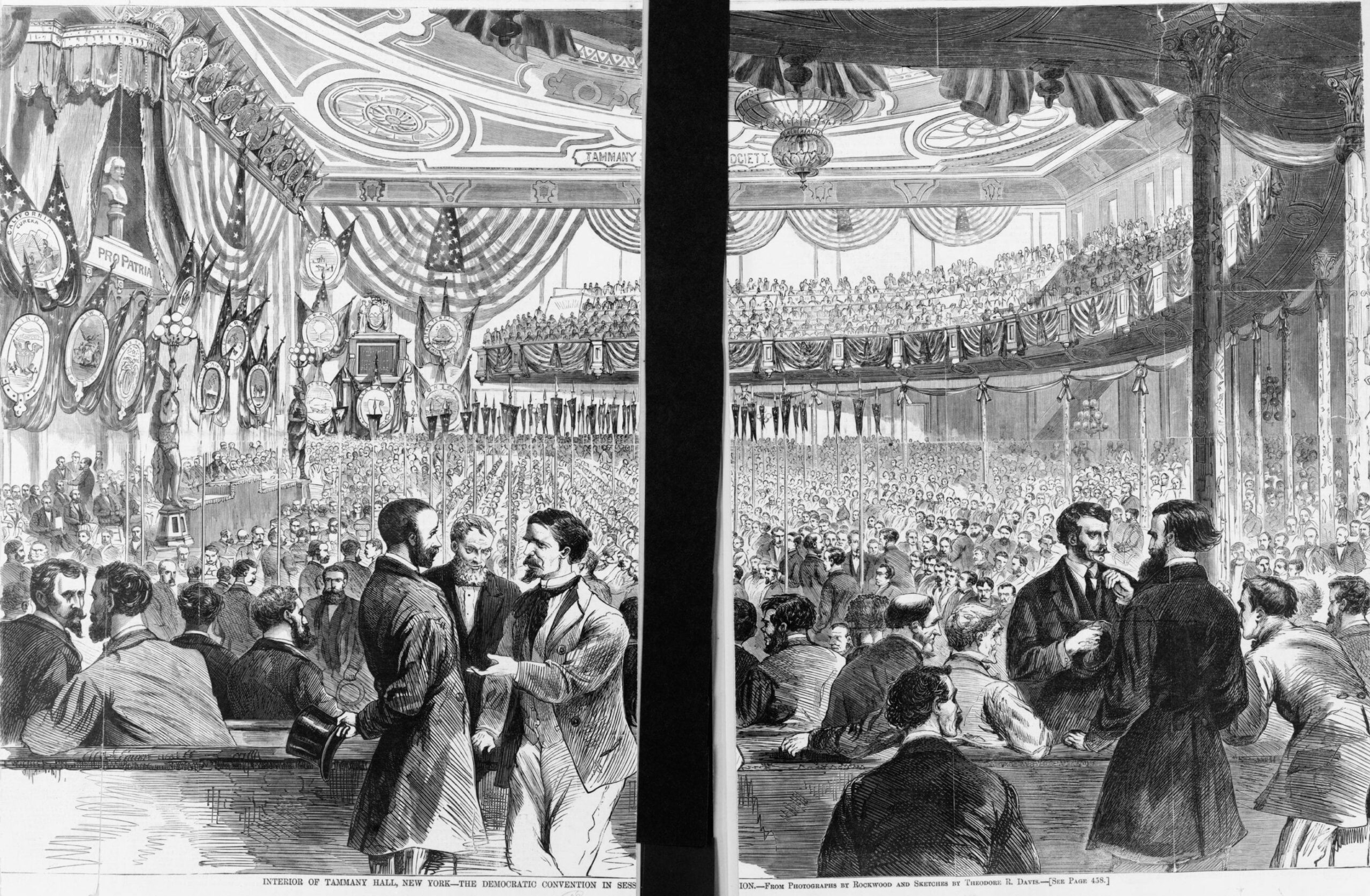

Alexander Stephens had been a Whig Congressman from Georgia in the 1840s and 1850s. He opposed Georgia’s secession from the Union. Yet, as Georgia followed the rest of the South in secession from the Union, Stephens was elected Vice President of the Confederacy. As Vice President, he delivered the famous “Cornerstone speech” in March 1861, arguing that the Confederacy was the first government based on “great physical, philosophical, and moral truth” that “the Negro is not equal to the white man” and that a black’s “subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.” Stephens was captured and imprisoned after the Union victory. President Andrew Johnson paroled Stephens after about five months in prison. Soon after his release, under Georgia’s new constitution made pursuant to Johnson’s restoration policy, the Georgia legislature elected Stephens as senator. Accepting the seat as Georgia’s Senator, Stephens delivered the speech excerpted here, outlining the policies that would guide his service.

The U.S. Congress, however, would not seat Stephens (as a former Confederate, he was disqualified from serving). The election of Stephens was a crucial piece of evidence for Republicans in Congress that Johnson’s policies were far too lenient. This diagnosis paved the way for the Reconstruction Acts and other more radical measures.

Source: Alexander H. Stephens, In Public and Private, With Letters and Speeches, Before, During, and Since the War, ed. Henry Cleveland (Philadelphia: National Publishing Company, 1866), 804, 805–06, 807, 810–11, 812, 813–14, 816–17, 817–18.

The great object with me now, is to see a restoration, if possible, of peace, prosperity, and constitutional liberty in this once happy, but now disturbed, agitated, and distracted country. To this end, all my energies and efforts, to the extent of their powers, will be devoted.

You ask my views on the existing state of affairs; our duties at the present, and the prospects of the future? . . .

Can these evils upon us – the absence of law; the want of protection and security of person and property . . . be removed? Or can those greater ones which threaten our very political existence, be averted? These are the questions.

It is true we have not the control of all the remedies . . . . Our fortunes and destiny are not entirely in our own hands. Yet there are some things that we may, and can, and ought, in my judgment, to do, from which no harm can come, and from which some good may follow, in bettering our present condition. . . .

The first great duty, then, I would enjoin at this time, is the exercise of the simple, though difficult and trying, but nevertheless indispensable quality of patience. Patience requires of those afflicted to bear and to suffer with fortitude whatever ills may befall them. . . . We are in the condition of a man with a dislocated limb, or a broken leg, and a very bad compound fracture at that. How it became broken should not be with him a question of so much importance, as how it can be restored to health, vigor, and strength. This requires of him as the highest duty to himself to wait quietly and patiently in splints and bandages, until nature resumes her active powers – until the vital functions perform their office. . . . We must or ought now, therefore, in a similar manner to discipline ourselves to the same or like degree of patience. . . . I know how trying it is to be denied representation in Congress, while we are paying our proportion of the taxes – how annoying it is to be even partially under military rule – and how injurious it is to the general interest and business of the country to be without post-offices and mail communications;1 to say nothing of divers other matters on the long list of our present inconveniences and privations. All these, however, we must patiently bear and endure for a season. . . .

Next to this, another great duty we owe to ourselves is the exercise of a liberal spirit of forbearance amongst ourselves.

The first step toward local or general harmony is the banishment from our breasts of every feeling and sentiment calculated to stir the discords of the past. Nothing could be more injurious or mischievous to the future of this country, than the agitation, at present, of questions that divided the people anterior to, or during the existence of the late war. On no occasion, and especially in the bestowment of office, ought such differences of opinion in the past ever to be mentioned, either for or against any one, otherwise equally entitled to confidence. These ideas or sentiments of other times and circumstances are not the germs from which hopeful organizations can now arise. . . . Great disasters are upon us and upon the whole country, and without inquiring how these originated . . . let us now as common sharers of common misfortunes, on all occasions, consult only as to the best means . . . to secure the best ends toward future amelioration. . . .

This view should also be born in mind, that whatever differences of opinion existed before the late fury of the war, they sprung mainly from differences as to the best means to be used . . . to secure the great controlling object of all – which was GOOD GOVERNMENT. Whatever may be said of the loyalty or disloyalty of any, in the late most lamentable conflict of arms, I think I may venture safely to say, that there was, on the parts of the great mass of the people of Georgia, and of the entire South, no disloyalty to the principles of the constitution of the United States. To that system of representative government; of delegated and limited powers; that establishment in a new phase, on this continent, of all the essentials of England’s Magna Charta, for the protection and security of life, liberty and property; with the additional recognition of the principle as a fundamental truth, that all political power resides in the people. With us it was simply a question as to where our allegiance was due in the maintenance of these principles – which authority was paramount in the last resort – State or federal. . . . It was with this view and this purpose secession was tried. That has failed.

. . .

. . . Our only alternative now is, either to give up all hope of constitutional liberty, or to retrace our steps, and to look for its vindication and maintenance in the forums of reason and justice, instead of on the arena of arms – in the courts and halls of legislation, instead of on the fields of battle.

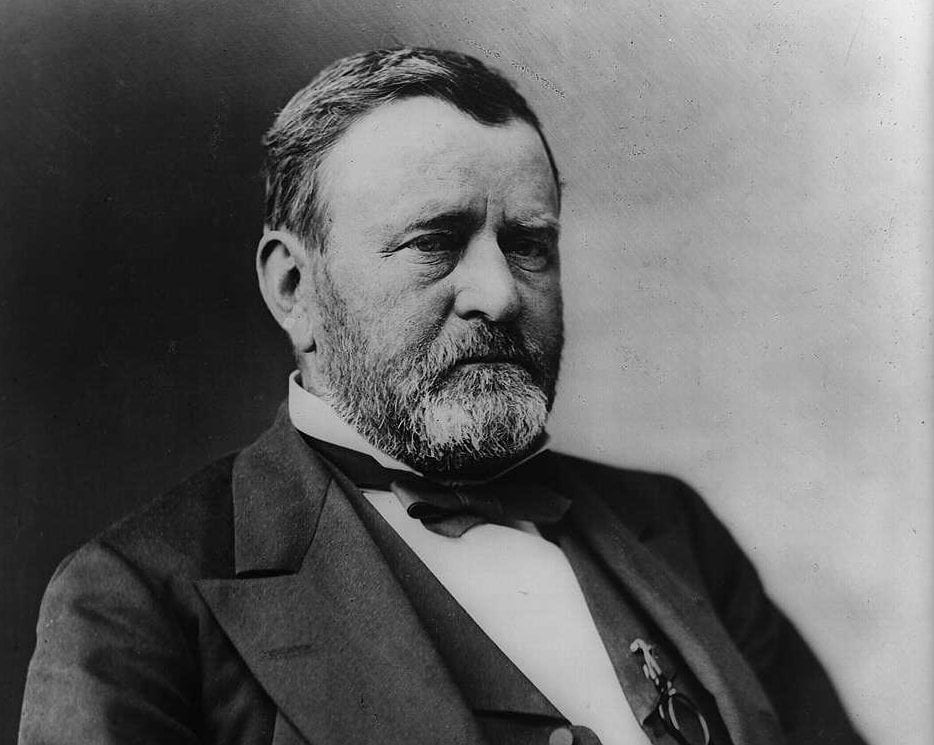

I am frank and candid in telling you right here, that our surest hopes, in my judgement, of these ends, are in the restoration policy of the President of the United States [Andrew Johnson].

. . .

I could enjoin no greater duty upon my countrymen now, North and South, than the exercise of that degree of forbearance which would enable them to conquer their prejudices. . . .

I say to you, and if my voice could extend throughout this vast country . . . among the first [of duties], looking to restoration of peace, prosperity and harmony in this land, is the great duty of exercising that degree of forbearance which will enable them to conquer their prejudices. Prejudices against communities as well as individuals.

And next to that, the indulgence of a Christian spirit of charity. . . .

. . . The exercise of patience, forbearance, and charity, therefore, are the three first duties I would at this time enjoin – and of these three, “the greatest is charity.”2

But to proceed. Another one of our present duties, is this: we should accept the issues of the war, and abide by them in good faith. . . . The people of Georgia have in convention revoked and annulled her ordinance of 1861, which was intended to sever her from the compact of Union of 1787. . . . Whether Georgia, by the action of her convention of 1861, was ever rightfully out of the Union or not, there can be no question that she is now in, so far as depends upon her will and deed. . . .

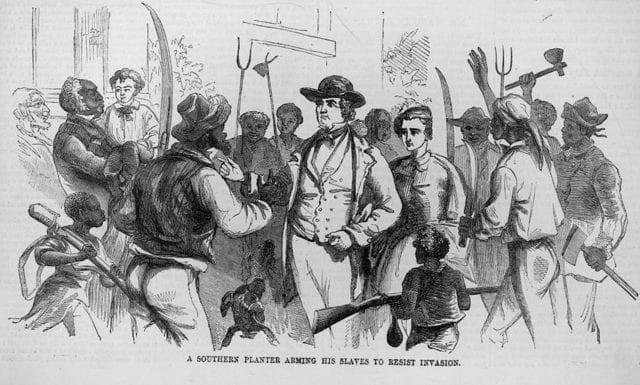

But with this change comes a new order of things. One of the results of the war is a total charge in our whole internal policy. Our former social fabric has been entirely subverted. . . . The relation heretofore, under our old system, existing between the African and European races, no longer exists. Slavery, as it was called, or the status of the black race, their subordination to the white, upon which all our institutions rested, is abolished forever, not only in Georgia, but throughout the limits of the United States. This change should be received and accepted as an irrevocable fact. . . .

All changes of systems or proposed reforms are but experiments and problems to be solved. Our system of self-government was an experiment at first. Perhaps as a problem it is not yet solved. Our present duty on this subject is not with the past or the future; it is with the present. . . .

This duty of giving this new system a fair and just trial will require of you, as legislators of the land, great changes in our former laws in regard to this large class of population. Wise and humane provisions should be made for them. It is not for me to go into detail. Suffice it to say on this occasion, that ample and full protection should be secured to them, so that they may stand equal before the law, in the possession and enjoyment of all rights of person, liberty and property. Many considerations claim this at your hands. Among these may be stated their fidelity in times past. They cultivated your fields, ministered to your personal wants and comforts, nursed and reared your children; and even in the hour of danger and peril they were, in the main, true to you and yours. To them we owe a debt of gratitude, as well as acts of kindness. This should also be done because they are poor, untutored, uninformed; many of them helpless, liable to be imposed upon, and need it. Legislation should ever look to the protection of the weak against the strong. Whatever may be said of the equality of races, or their natural capacity to become equal, no one can doubt that at this time this race among us is not equal to the Caucasian. This inequality does not lessen the moral obligations on the part of the superior to the inferior, it rather increases them. From him who has much, more is required than from him who has little.3 The present generation of them, it is true is far above their savage progenitors, who were at first introduced into this country, in general intelligence, virtue, and moral culture. This shows capacity for improvement. But in all the higher characteristics of mental development, they are still very far below the European type. What further advancement they may make, or to what standard they may attain, under a different system of laws every way suitable and wisely applicable to their changed condition, time alone can disclose. I speak of them as we now know them to be; having no longer the protection of a master, or legal guardian, they now need all the protection which the shield of the law can give.

But, above all, this protection should be secured, because it is right and just that it should be, upon general principles. All governments in their organic structure, as well as in their administration, should have this leading object in view: the good of the governed. . . . In legislation, therefore, under the new system, you should look to the best interest of all classes; their protection, security, advancement and improvement, physically, intellectually, and morally. All obstacles, if there be any, should be removed, which can possibly hinder or retard, the improvement of the blacks to the extent of their capacity. All proper aid should be given to their own efforts. Channels of education should be opened up to them. Schools, and the usual means of moral and intellectual training, should be encouraged among them. This is the dictate, not only of what is right and proper, and just in itself, but it is also the promptings of the highest considerations of interest. It is difficult to conceive a greater evil or curse, that could befall our country, stricken and distressed as it now is, than for so large a portion of its population, as this class will quite probably constitute amongst us, hereafter, to be reared in ignorance, depravity and vice. In view of such a state of things well might the prudent even now look to its abandonment. . . . The most vexed questions of the age are social problems. These we have heretofore had but little to do with; we were relieved from them by our peculiar institution. Emancipation of the blacks, with its consequences, was ever considered by me with much more interest as a social question, one relating to the proper status of the different elements of society, and their relations toward each other, looking to the best interest of all, than in any other light. . . . This problem . . . is now upon us, presenting one of the most perplexing questions of the sort that any people ever had to deal with. Let us resolve to do the best we can with it. . . .

. . . [L]et all patriots . . . rally, in all elections everywhere, to the support of him, be he who he may, who bears the standard with “Constitutional Union” emblazoned on its fold. President Johnson is now, in my judgment, the chief great standard-bearer of these principles, and in his efforts at restoration should receive the cordial support of every well-wisher of his country.

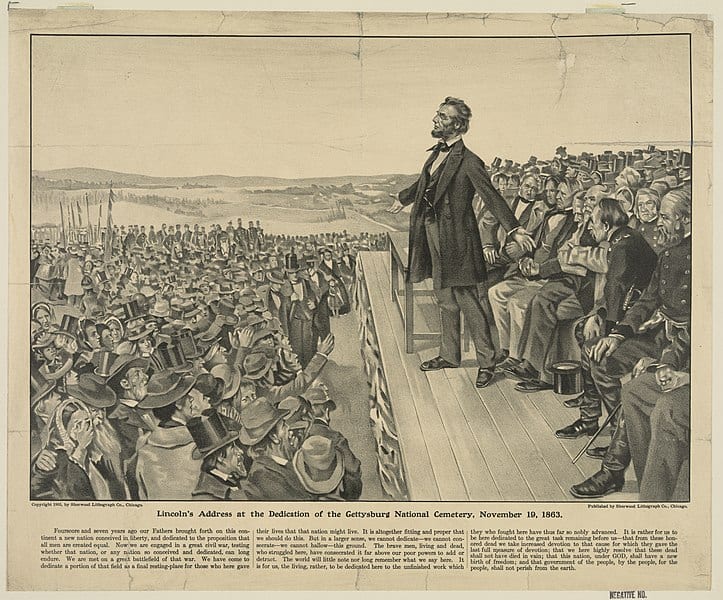

In this consists, on this rests, my only hope. Should he be sustained, and the government be restored to its former functions, all the States brought back to their practical relations under the constitution, our situation will be greatly changed from what it was before. A radical and fundamental change . . . has been made in that organic law.4 We shall have lost what was known as our “peculiar institution” which was so intertwined with the whole framework of our State body politic. We shall have lost nearly half the accumulated capital of a century. But we shall have still left all the essentials of free government, contained and embodied in the old constitution. . . . With these, even if we had to begin entirely anew, the prospect before us would be much more encouraging than the prospect was before them, when they fled from the oppressions of the old world, and sought shelter and homes in this then wilderness land. The liberties we begin with, they had to achieve. . . .

The old Union was based upon the assumption, that it was for the best interest of the people of all the States to be united as they were, each State faithfully performing to the people of the other States all their obligations under the common compact. I always thought this assumption was founded upon broad, correct, and statesman-like principles. I think so yet. . . . And now, after the severe chastisements of war, if the general sense of the whole country shall come back to the acknowledgment of the original assumption, that it is for the best interests of all the States to be so united, as I trust it will; the States still being “separate as the billows but one as the sea;” I can perceive no reason why, under such restoration, we as a whole, with “peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations and entangling alliances with none,”5 may not enter upon a new career, exciting increased wonder in the old world, by grander achievements hereafter to be made, than any heretofore attained, by the peaceful and harmonious workings of our American institutions of self-government. . . .

- 1. President Johnson had said that the mails were running in his First Annual Address.

- 2. 1 Corinthians 13:13.

- 3. Stephens paraphrases Luke 12:48: “For unto whomsoever much is given, of him shall be much required.”

- 4. the fundamental system of laws or principles that defines the way a nation is governed

- 5. a phrase from Thomas Jefferson’s First Inaugural Address

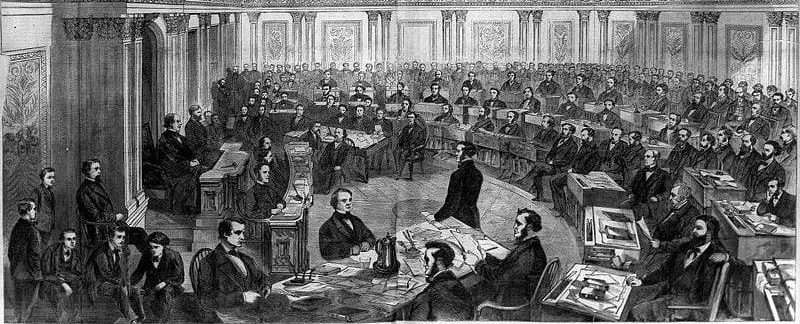

Congressional Debate on the 14th Amendment

February 28, 1866

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.