In the universe of God there are no accidents. From the fall of a sparrow to the fall of an empire or the sweep of a planet, all is according to Divine Providence, whose laws are everlasting. No accident gave to his country the patriot we now honor. No accident snatched this patriot, so suddenly and so cruelly, from his sub-lime duties. Death is as little an accident as life. Never, perhaps, in history has this Providence been more conspicuous than in that recent procession of events, where the final triumph is wrapped in the gloom of tragedy. It is our present duty to find the moral of this stupendous drama.

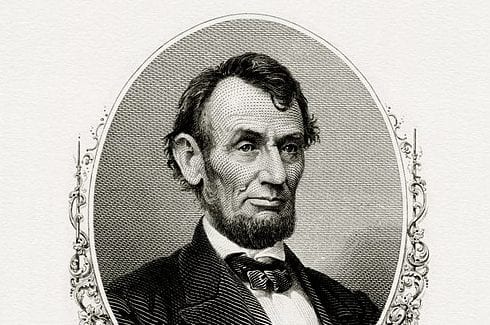

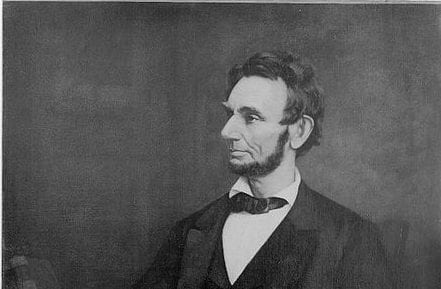

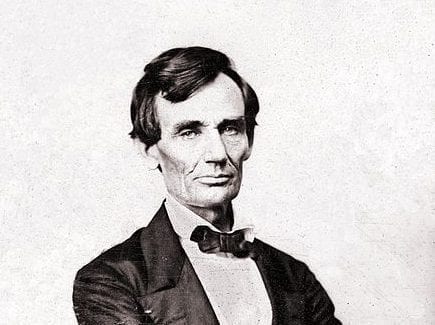

For the second time in our annals, the country is summoned by the President to unite, on an appointed day, in commemorating the life and character of the dead. The first was on the death of George Washington, when, as now, a day was set apart for simultaneous eulogy throughout the land, and cities, towns, and villages all vied in tribute, Since this early observance for the Father of his Country more than half a century has passed, and now it is repeated in memory of Abraham Lincoln.

Thus are Washington and Lincoln associated in the grandeur of their obsequies. But this is not accidental. It is from the nature of things, and because the part Lincoln was called to perform resembled in character the part performed by Washington. The work left undone by Washington was continued by Lincoln. Kindred, in service, kindred in patriotism, each is surrounded in death by kindred homage. One sleeps in the East, the other sleeps in the West; and thus, in death, as in life, one is the complement of the other.

The two might be compared after the manner of Plutarch; but it must suffice for the present to glance only at points of resemblance and of contrast, so as to recall the parts they respectively performed.

Each was head of the Republic during a period of surpassing trial; and each thought only of the public good, simply, purely, constantly, so that single-hearted devotion to country will always find a synonym in their names. Each was national chief during a time of successful war. Each was representative of his country at a great epoch of history. Here, perhaps, resemblance ends and contrast begins. Unlike in origin, conversation, and character, they were unlike also in the ideas they served, except as each was servant of his country. The war conducted by Washington was unlike the war conducted by Lincoln, as the peace which crowned the arms of the one was unlike the peace which began to smile upon the other. The two wars did not differ in scale of operations and in tramp of mustered hosts more than in the ideas involved. The first was for National Independence; the second was to make the Republic one and indivisible, on the indestructible foundation of Liberty and Equality. The first cut the connection with the mother country, and opened the way to the duties and advantages of Popular Government; the second will have failed, unless it consummates all the original promises of the Declaration our fathers took upon their lips when they became a Nation. In the relation of cause and effect the first was natural precursor and herald of the second. National Independence became the first epoch in our history, whose mighty import was exhibited when Lafayette boasted to the First Consul of France, that, though its battles were but skirmishes, they decided the fate of the world.

The Declaration of our fathers, entitled simply “The Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of America,” is known familiarly as the Declaration of Independence, because the remarkable words with which it concludes made independence the final idea, to which all else was tributary. Thus did the representatives of the United States of America in General Congress assembled solemnly publish and declare “that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States; that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown; and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved;…and for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.” To sustain this mutual pledge Washington drew his sword and led the national armies, until at last, by the Treaty of Peace in 1783, Independence was acknowledged.

Had the Declaration been confined to this pledge, it would have been less grand. Much as it might have been to us, it would have been less of a warning and trumpet-note to the world. There were two other pledges it made. One was proclaimed in the designation “United States of America,” which it adopted as the national name; and the other was proclaimed in those great words, fit for the baptismal vows of a Republic,–“We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” By the sword of Washington Independence was secured; but the Unity of the Republic and the principles of the Declaration were left exposed to question. From that early day, through various chances, they were assailed and openly dishonored, until at last the Republic was constrained to take up arms in their defence. And yet, since enmity to the Union proceeded entirely from enmity to the great ideas of the Declaration, history must record that the question of the Union itself was absorbed in the grander conflict to uphold the primal truths our fathers had solemnly proclaimed.

Such are the two great wars where these two chiefs bore each his part. Washington fought for National Independence, and triumphed, making his country an example of mankind. Lincoln drew a reluctant sword to save those great ideas, essential to the life and character of the Republic, which unhappily the sword of Washington failed to put beyond the reach of assault.

By no accident did these two great men become representatives of their country at these two different epochs, so alike in peril, and yet so unlike in the principles involved. Washington was the natural representative of National Independence. He might also have represented National Unity, had this principle been challenged to bloody battle during his life; for nothing was nearer his heart than the consolidation of our Union, which in his letter to Congress transmitting the Constitution, he declares to be “the greatest interest of every true American.” Then again, in a remarkable letter to John Jay, he plainly says that he does “not conceive we can exist long as a nation without having lodged somewhere a power which will pervade the whole Union in as energetic a manner as the authority of the State governments extends over the several States.” But another person was needed, of different birth and simpler life, to represent the ideas now impugned.

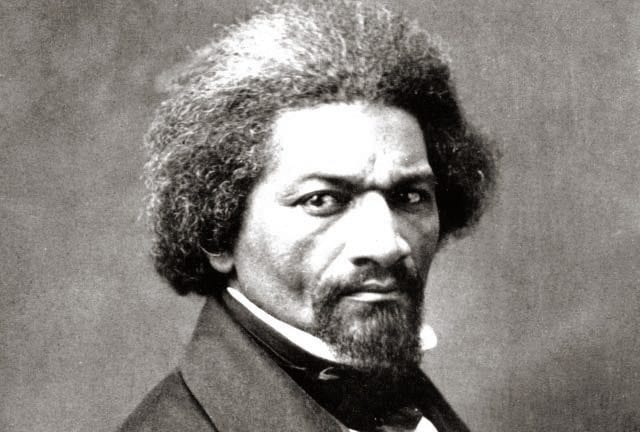

Washington was of ancient family, traced in English heraldry. Some of his ancestors sleep in close companionship with the noble name of Spencer. By inheritance and marriage he was rich in lands, and, let it be said in respectful sorrow, rich also in slaves, so far as slaves breed riches rather than curses. At the age of fourteen he refused a commission as midshipman in the British Navy. At the age of nineteen he was Adjutant General, with the rank of major. At the age of twenty-one he was selected by the British Governor of Virginia as Commissioner to the French posts. At the age of twenty-two he was at the head of a regiment, and was thanked by the House of Burgesses. Early in life he became an observer of forma and ceremony. Always strictly just, according to prevailing principles, and at his death ordering the emancipation of his slaves, he was more a general and statesman than philanthropist; nor did he seem inspired, beyond the duties of patriotism, to active sympathy with Human Rights. In the ample record of what he wrote or said there is no word of adhesion to the great ideas of the Declaration. Such an origin, such an early life, such opportunities, such a condition, such a character, were all in contrast with the origin, early life, opportunities, condition, and character of him we commemorate to-day.

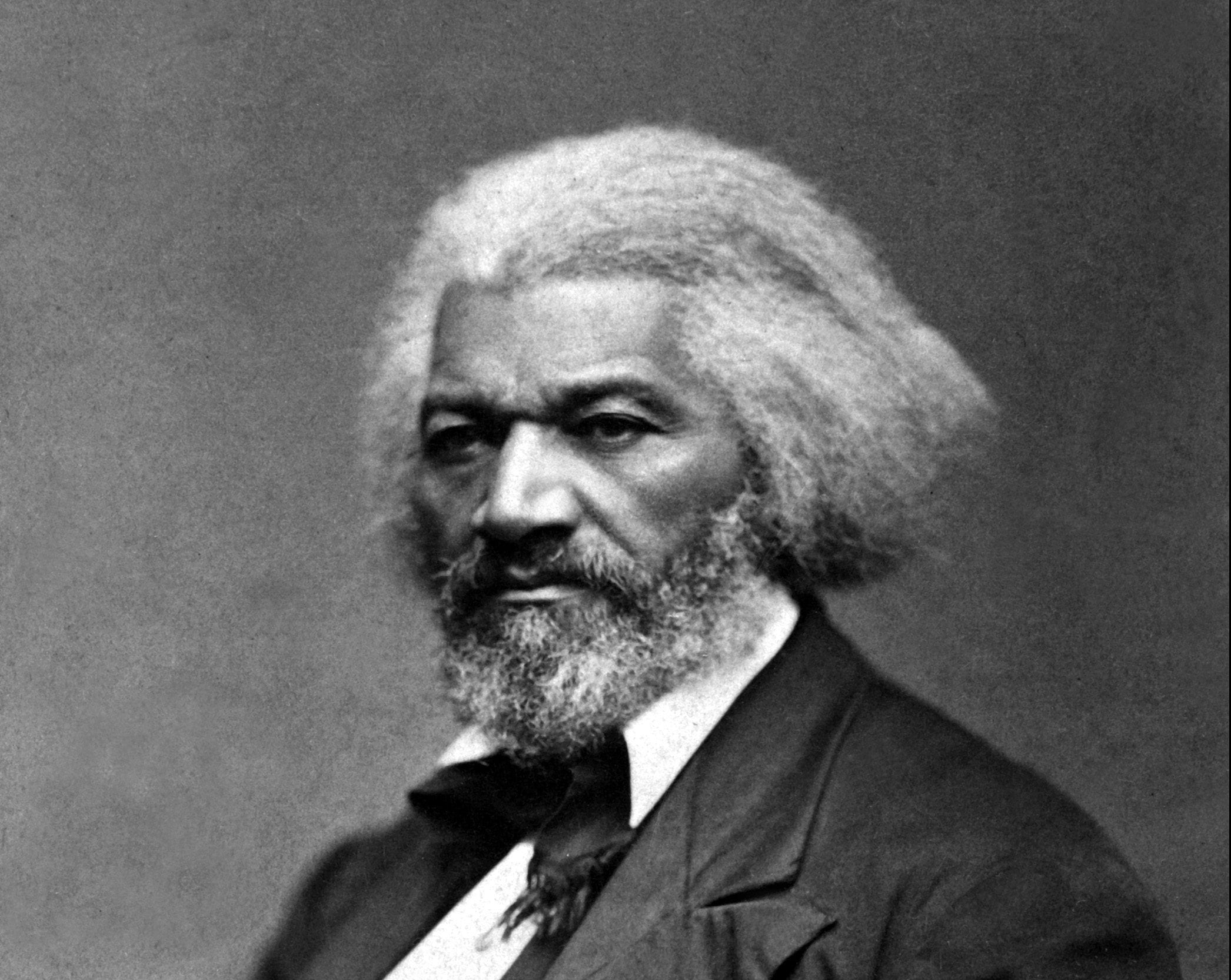

Abraham Lincoln was born, and, until he became President, always lived in a part of the country which at the period of the Declaration of Independence was a savage wilderness. Strange, but happy, Providence, that a voice from that savage wilderness, now fertile in men, was inspired to uphold the pledges and promises of the Declaration! The Unity of the Republic, on the indestructible foundation of Liberty and Equality, was vindicated by the citizen of a community which had no existence when the Republic was formed.

His family may be traced to Quaker stock in Pennsylvania, but it removed first to Virginia, and then, as early as 1780, to the wilds of Kentucky, which at that time was only an outlying territory of Virginia. His grandfather and father both lived in peril from Indians, and the former perished by their knife. The future President was born in a log-house. His mother could read, and perhaps write. His father could do neither, except so far as to sign his name rudely, like a noble of Charlemagne. Trial, privation, and labor entered into his early life. Only at seven years of age, for a very brief period, could he enjoy school, carrying with him Dilworth’s Spelling-Book, one of the three volumes that formed the family library. Shortly afterwards his father turned his back upon that Slavery which disfigured Kentucky, and placing his poor effects upon a raft which his son had helped him construct, set his face towards Indiana, already guarded against Slavery by the famous Northwestern Ordinance. In this painful journey the son, who was only eight years old, bore his share of the burdens. On reaching the chosen home in a land of Liberty, the son aided his father in building the cabin, composed of logs fastened together by notches, and filled in with mud, where for twelve years afterwards he grew in character and knowledge, as in stature, learning to write as well as read, and especially enjoying Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, Aesop’s Fables, Weems’s Life of Washington, and the Life of Henry Clay. At the age of ten he lost his mother. At the age of nineteen he became a hired hand, at $10 dollars a month, on a flatboat laden with stores for the plantations on the Mississippi, and in this way floated on that lordly river to New Orleans, little dreaming that only a few years later iron-clad navies would at his command float on that same proud stream. Here also was he learner. From the slaves he saw on the banks he took a lesson of Liberty, which gained new charms by comparison with Slavery.

In 1830 the father removed to Illinois, transporting his goods in a wagon drawn by oxen, and the future President, then twenty-one years of age, drove the team. Another cabin was built in primitive rudeness, and the future President split the rails for the fence to inclose the lot. These rails have become classical in our history, and the name of rail-splitter has been more than the degree of a college,–not that the splitting of rails is any way meritorious, but because the people are proud to trace aspiring talent back to humble beginnings, and they found in this tribute new opportunity to vindicate the dignity of free labor, and repel the insolent pretensions of Slavery.

His youth was now spent, and at the age of twenty-one he left his father’s house to begin the world. A small bundle, a laughing face, and an honest heart,—these were his simple possessions, together with that unconscious character and intelligence which his country afterwards learned prize. In the long history of worth depressed there is no instance of such contrast between the depression and the triumph,—unless, perhaps, his successor as President may share with him this distinction. No academy, no university, no Alma Mater of science or learning had nourished him. No government had taken him by the hand and given him the gift of opportunity. No inheritance of land or money had fallen to him. No friend stood by his side. He was alone in poverty: and yet not all alone. There was God above, who watches all, and does not desert the lowly. Plain in person, life, and manners, and knowing absolutely nothing of form or ceremony, for six months with a village schoolmaster as his only teacher, he grew up in companionship with the people, with Nature, with trees, with the fruitful corn, and with the stars. While yet a child, his father had borne him away from a soil wasted by Slavery, and he was now citizen of a Free State, where Free Labor had been placed under safeguard of irreversible compact and fundamental law. And thus he took leave of youth, happy at least that he could go forth under the day-star of Liberty.

The early hardships were prolonged into manhood. He labored on a farm as hired hand, and then a second time in a flatboat measured the winding Mississippi to its mouth. At the call of the Governor of Illinois for troops against Black Hawk, the Indian chief, he sprang forward with patriotic ardor, most prompt to enlist at the recruiting station in his neighborhood. The choice of his associates made him captain. After the war he became surveyor, and to his death retained a practical and scientific knowledge of this business. Here again was a parallel with Washington. In 1834 he was elected to the Legislature of Illinois, and three years later was admitted to the practice of the law. He was now twenty-eight years old, and, under the benignant influence of republican institutions, he had already entered upon the double career of lawyer and legislator, with the gates of the mysterious Future slowly opening before him.

How well he served in these two characters I need not stop to tell. It is enough, if I exhibit the stages of advance, that you may understand how he became representative of his country at so grand a moment of history. It is needless to say that his opportunities of study as a lawyer were small, but he was industrious in each individual case, and thus daily added to his stores of professional experience. Faithful in all things, most conscientious in conduct at the bar, so that he could not be unfair to the other side, and admirably sensitive to the behests of justice, so that he could not argue on the wrong side, he acquired a name for honesty, which, beginning with the community where he lived, became proverbial throughout his State,—while his genial, mirthful, overflowing nature, apt at anecdote and story, made him, where personally known, a favorite companion. His opinions on public questions were formed early, under the example and teaching of Henry Clay, and he never departed from them, though constantly tempted, or pressed by local majorities, in the name of a false democracy. It is interesting to know that thus early he espoused those two ideas which entered so largely into the terrible responsibilities of his last years,—I mean the Unity of the Republic, and the supreme value of Liberty. He did not believe that a State, in its own mad will, had a right to break up this Union. As reader of Congressional speeches, and student of what was said by the political teachers of that day, he was no stranger to those marvelous efforts of Daniel Webster, when, in reply to the treasonable pretensions of Nullification, the great orator of Massachusetts asserted the indestructibility of the Union, and the folly of those who assail it. On the subject of Slavery, he had the experience of his own family and the warnings of his own conscience. Naturally, one of his earliest acts in the Legislature of Illinois was a protest in the name of Liberty.

At a later day, he was in Congress for a single term, beginning in December, 1847, being the only Whig Representative from Illinois. His speeches during this brief period have the characteristics of his later productions. They are argumentative, logical, and spirited, with quaint humor and sinewy sententiousness. His votes were constant against Slavery. For the Wilmot Proviso he voted, according to his own statement, “in one way and another, about forty times.” His vote is recorded against the pretence that slaves are property under the Constitution. From Congress he passed again to his profession. The day was at hand, when all his powers, enlarged by experience and quickened to highest activity, would be needed to repel that haughty domination already overshadowing the Republic.

The next field of conflict was in his own State, with no less an antagonist than Stephen A. Douglas, at that time in alliance with the Slave Power. The too famous Kansas and Nebraska Bill, introduced by the latter into the Senate, assumed to set aside the venerable safeguard of Freedom in the territory west of Missouri, under pretence of allowing the inhabitants “to vote Slavery up or to vote it down,” and this barbarous privilege was called by the fancy name of Popular Sovereignty. The champion of Liberty did not hesitate to denounce this most baleful measure in a series of popular addresses, where truth, sentiment, humor, and argument all blended. As the conflict continued, he was brought forward for the Senate against the able author of this measure. The debate that ensued is one of the most memorable in our political history, whether we consider the principles involved or the way it was conducted.

It commenced with a close, well-woven speech from the Republican candidate, showing insight into the actual condition of things, in which were these memorable words: “’A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this Government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved, I do not expect the house to fall, but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other.” Here was the true starting-point. Only a few days before his death, in reply to my inquiry, if at the time he had any doubt about this declaration, he said, “Not in the least. It was clearly true, and time has justified me.” With like plainness he exposed the Douglas pretence of Popular Sovereignty as meaning simply, “that, if any one man choose to enslave another, no third man shall be allowed to object,” and he announced his belief in “the existence of a conspiracy to perpetuate and nationalize Slavery,” of which the Kansas and Nebraska Bill and the Dred Scott decision were essential parts. Such was the character of this debate at the beginning, and so it continued on the lips of our champion to the end.

The inevitable topic to which he returned with most frequency, and to which he clung with all the grasp of his soul, was the practical character of the Declaration of Independence in announcing the Liberty and Equality of all Men. No idle words were there, but substantial truth, binding on the conscience of mankind. I know not if this grand pertinacity has been noticed before; but I deem it my duty to say, that to my mind it is by far the most important feature of that controversy, and one of the most interesting incidents in the biography of the speaker. Nothing previous to his nomination for the Presidency is comparable to it. Plainly his whole subsequent career took impulse and complexion from that championship. And here, too, is our first debt of gratitude. The words he then uttered live after him, and nobody can hear of that championship without feeling a new motive to fidelity in in the cause of Liberty and Equality.

As early as 1854, in a speech at Peoria against the Kansas and Nebraska Bill, after denouncing Slavery as a “monstrous injustice,” which enables the enemies of free institutions to taunt us as hypocrites, and causes the real friends of Freedom to doubt our sincerity, he complains especially that “it forces so many really good men amongst ourselves into an open war with the very fundamental principles of civil liberty, criticizing the Declaration of Independence.” Thus, according to him, was criticism of the Declaration of Independence the climax of infidelity as citizen.

Mr. Douglas opened the debate, on his side, at Chicago, July 9, 1858, by a speech, where he said, among other things, “I am opposed to negro equality. I repeat, that this nation is a white people….I am opposed to taking any step that recognizes the negro man or the Indian as the equal of the white man. I am opposed to giving him a voice in the administration of the Government.” Thus was the case stated on the side of Slavery.

To this speech the Republican candidate replied the next evening, and he did not forget his championship of the Declaration. Quoting the great words, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” he proceeds to say:–

“This is the electric cord in that Declaration that links the hearts of patriotic and liberty-loving men together, that will link those patriotic hearts as long as the love of freedom exists in the minds of men throughout the world.—I should like to know if taking this old Declaration of Independence, which declares that all men are equal, upon principle, and making exceptions to it, where will it stop? If one man says it does not mean the negro, why not another say it does not mean some other man? If that Declaration is not the truth, let us get the statute-book in which we find it and tear it out. Who is so bold as to do it? If it is not true, let us tear in out [Cries of “No, no!”] Let us stick to it, then; let us stand firmly by it, then.”

Noble words, worthy of perpetual memory! And he finished his speech with a farewell truly apostolic:–

“I leave you, hoping that the lamp of Liberty will burn in your bosoms until there shall no longer be a doubt that all men are created free and equal.”

He has left us now, and for the last time, and I catch the closing benediction of that speech, already sounding through the ages, like a choral harmony.

The debate continued from place to place. At Bloomington, July 16th, Mr. Douglas denied again that colored persons could be citizens, and then broke forth upon the champion:—

“I will not quarrel with Mr. Lincoln for his views on that subject. I have no doubt he is conscientious in them. I have not the slightest idea but that he conscientiously believes that a negro ought to enjoy and exercise all the rights and privileges given to white men; but I do not agree with him….I believe that this government of ours was founded on the white basis. I believe that it was established by white men. . . . I do not believe that it was the design or intention of the signers of the Declaration of Independence or the framers of the Constitution to include negroes, Indians, or other inferior races, with white men, as citizens. . . . He wants them to vote. I am opposed to it. If they had a vote, I reckon they would all vote for him in preference to me, entertaining the views I do.”

Then again at Springfield, the next day, Mr. Douglas repeated his denial that the colored man was embraced by the Declaration of Indeendence, and thus argued for the exclusion:—

“Remember that at the time the Declaration was put forth, every one of the Thirteen Colonies were slaveholding colonies,—every man who signed that Declaration represented slaveholding constituents. Did those signers mean by that act to charge themselves and all their constituents with having violated the law of God in holding the negro in an inferior condition to the white man? And yet, if they included negroes in that term, they were bound, as conscientious men, that day and that hour, not only to have abolished Slavery throughout the land, but to have conferred political rights and privileges on the negro, and elevated him to an equality with the white man. . . . The Declaration of Independence only included the white people of the United States.”

On the same evening, at Springfield, the Republican candidate, while admitting that negroes are not “our equals in color,” thus again spoke for the comprehensive humanity of the Declaration:—

“I adhere to the Declaration of Independence. If Judge Douglas and his friends are not willing to stand by it, let them come up and amend it. Let them make it read, that all men are created equal except negroes. Let us have it decided, whether the Declaration of Independence, in this blessed year of 1858, shall be thus amended. In his construction of the Declaration last year, he said it only meant that Americans in America were equal to Englishman in England. Then, when I pointed out to him that by that rule he excludes the Germans, the Irish, the Portuguese, and all the other people who have come amongst us since the Revolution, he reconstructs his construction. In his last speech he tells us it meant Europeans. I press him a little further, and ask if it meant to include the Russians in Asia. Or does he mean to exclude that vast population from the principles of our Declaration of Independence? I expect erelong he will introduce another amendment to his definition. He is not at all particular. . . . It may draw white men down, but it must not lift negroes up.”

Words like these are gratefully remembered. They make the Declaration, what the Fathers intended, no mean proclamation of oligarchic egotism, but a charter and freehold for all mankind. At Ottawa, August 21st, Mr. Douglas, still excluding the colored men from the Declaration, exclaimed:—

“I believe this Government was made on the white basis. I believe it was made by white men, for the benefit of white men and their posterity forever.”

Again the Republican champion took up the strain.

“Henry Clay once said of a class of men who would repress all tendencies to Liberty and ultimate Emancipation, that they must, if they would do this, go back to the era of our Independence, and muzzle the cannon which thunders its annual joyous return,—they must blow out the moral lights around us,—they must penetrate the human soul, and eradicate there the love of Liberty; and then, and not till then, could they perpetuate Slavery in this country. To my thinking, Judge Douglas is, by his example and vast influence, doing that very thing in this community, when he says that the negro has nothing in the Declaration of Independence.”

At Jonesboro, September 15th, Mr. Douglas once more assailed the rights of the colored race.

“I am aware that all the Abolition lecturers that you find travelling about through the country are in the habit of reading the Declaration of Independence to prove that all men were created equal, and endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Mr. Lincoln is very much in the habit of following in the track of Lovejoy in this particular, by reading that part of the Declaration of Independence to prove that the negro was endowed by the Almighty with the inalienable right of equality with white men. Now I say to you, my fellow-citizens, that, in my opinion, the signers of the Declaration had no reference to the negro whatever, when they declared all men to be created equal.”

At Galesburg, October 7th, the future president again upheld the Declaration:–

“The Judge has alluded to the Declaration of Independence, and insisted that negroes are not included in that Declaration, and that it is a slander upon the framers of that instrument to suppose that negroes were meant therein; and he asks you, Is it possible to believe that Mr. Jefferson, who penned the immortal paper, could have supposed himself applying the language of that instrument to the negro race, and yet held a portion of that race in slavery? Would he not at once have freed them? I only have to remark upon this part of the Judge’s speech, that I believe the entire records of the world, from the date of the Declaration of Independence up to within three years ago, may be searched in vain for one single affirmation from one single man, that the negro was not included in the Declaration. And I will remind Judge Douglas and this audience, that, while Mr. Jefferson was the owner of slaves, as undoubtedly he was, in speaking upon this very subject, he used the strong language, that ’he trembled for his country when he remembered that God was just.’”

And at Alton, October 15th, he renewed this same testimony.

“I assert that Judge Douglas and all his friends may search the whole records of the country, and it will be a matter of great astonishment to me, if they shall be able to find that one human being three years ago had ever uttered the astounding sentiment that the term ’all men’ in the Declaration did not include the negro. Do not let me be misunderstood. I know that more than three years ago there were men, who, finding this assertion constantly in the way of their schemes to bring about the ascendency and perpetuation of Slavery, denied the truth of it. I know that Mr. Calhoun, and all the politicians of his school, denied the truth of the Declaration. I know that it ran along in the mouth of some Southern men for a period of years, ending at last in that shameful, though rather forcible, declaration of Pettit, of Indiana, upon the floor of the United States Senate, that the Declaration of Independence was, in that respect, ’a self-evident lie,’ rather than a self-evident truth. But I say, with a perfect knowledge of all this hawking at the Declaration without directly attacking it, that three years ago there never lived a man who had ventured to assail it in the sneaking way of pretending to believe it, and then asserting it did not include the negro.”

In another speech, during the same political contest, the champion spoke immortal words. After setting forth the sublime opening of the Declaration by our fathers, he said:—

“This was their majestic interpretation of the economy of the universe. This was their lofty and wise and noble understanding of the justice of the Creator to His creatures,—yes, Gentlemen, to all His creatures, to the whole great family of man.”

Lifted by the cause in which he was engaged, he appealed to his fellow-countrymen in tones of pathetic eloquence:—

“Think nothing of me, take no thought for the political fate of any man whomsoever, but come back to the truths that are in the Declaration of Independence. You may do anything with me you choose, if you will but heed these sacred principles. You may not only defeat me for the Senate, but you may take me and put me to death. While pretending no indifference to earthly honors, I do claim to be actuated in this contest by something higher than an anxiety for office. I charge you to drop every paltry and insignificant thought for any man’s success. It is nothing. I am nothing. Judge Douglas is nothing. But do not destroy that immortal emblem of humanity, the Declaration of Independence.”

Thus, at that early day, before war had overshadowed the land, was he ready for the sacrifice. “Take me and put me to death,” said he, “but do not destroy that immortal emblem of humanity, the Declaration of Independence.” He has been put to death by the enemies of the Declaration; but, though dead, he will continue to guard that great title-deed of the human race.

The debate ended. An immense vote was cast. There were 126,084 votes for the Republican candidates, 121,940 for the Douglas candidates, and 5,091 for the Lecompton candidates, another class of Democrats; but the supporters of Mr. Douglas had a majority of eight on joint ballot in the Legislature, and he was reelected to the Senate.

Again returned to his profession, the future President did not forget the Declaration of Independence. To the Republicans of Boston, who had invited him to unite with them in celebrating the birthday of Thomas Jefferson, he sent an answer, under date of April 6, 1859, which is a gem in political literature, and here also he asserts the supremacy of those truths for which he had battled so well. In him the West spoke to the East, pleading for Human Rights, as declared by our fathers.

“But, soberly, it is now no child’s play to save the principles of Jefferson from total overthrow in this nation.

“One would state with great confidence that he could convince any sane child that the simpler propositions of Euclid are true; but, nevertheless, he would fail utterly with one who should deny the definitions and axioms. The principles of Jefferson are the definitions and axioms of free society and yet they are denied and evaded with no small show of success. One dashingly calls them ’glittering generalities’; another bluntly calls them ’self-evident lies’; and others insidiously argue that they apply only to ’superior races.’

“These expressions, differing in form, are identical in object and effect,—the supplanting the principles of free government, and restoring those of classification, caste, and legitimacy. They would delight a convocation of crowned heads plotting against the people. They are the vanguard, the miners and sappers of returning despotism. We must repulse them, or they will subjugate us.

“This is a world of compensations; and he who would be no slave must consent to have no slave. Those who deny freedom to others deserve it not for themselves, and, under a just God, cannot long retain it.

“All honor to Jefferson,—the man who, in the concrete pressure of a struggle for national independence by a single people, had the coolness, forecast, and capacity to introduce into a merely revolutionary document an abstract truth, applicable to all men and all times, and so to embalm it there that to-day, and in all coming days, it shall be a rebuke and a stumbling-block to the harbingers of reappearing tyranny and oppression!”

Next winter the Western champion appeared at New York, and in a remarkable address at the Cooper Institute, February 27, 1860, vindicated the policy of the Fathers and the principles of the Republican party. Showing with curious skill and minuteness the original understanding on the power of Congress over Slavery in the Territories, he demonstrated that the Republican party was not in any just sense sectional; and then exposed the perils from the pretensions of slave-masters, who, not content with requiring that “we must arrest and return their slaves with greedy pleasure,” insisted that the Constitution must be so interpreted as to uphold the idea of property in man. The whole address was subdued and argumentative, while each sentence was like a driven nail, with a concluding rally that was a bugle-call to the lovers of right. “Let us have faith,” said he, “that right makes might, and in that faith let us to the end dare to do our duty as we understand.”

A few months later, this champion of the Right, who would not see the colored man shut out from the promises of the Declaration, and insisted upon the exclusion of Slavery from the Territories, after summoning his countrymen to their duty, was nominated by a great political party as candidate for President. Local considerations, securing to him the support of certain States beyond any other candidate, exercised a final influence in determining this selection; but it is easy to see how, from position, character, and origin, he was at that moment especially the representative of his country. The Unity of the Republic was menaced: he was from that vast controlling Northwest which would never renounce its communications with the sea, whether by the Mississippi or by eastern avenues. The birthday Declaration of the Republic was dishonored in the denial of its primal truths: he was already known as a volunteer in its defence. Republican institutions were in jeopardy: he was the child of humble life, through whom republican institutions would stand confessed. These things, so obvious now in the light of history, were less apparent then in the turmoil of party. But that Providence in whose hands are the destinies of nations, which had found out Washington to conduct his country through the War of Independence, now found out Lincoln to wage the new battle for the Unity of the Republic on the foundations of Liberty and Equality.

The election took place. Of the popular votes, Abraham Lincoln received 1,866,452, represented by 180 electoral ballots; Stephen A. Dougals received 1,375,157, represented by 12 electoral ballots; John C. Breckinridge received 847,953, represented by 72 electoral ballots; and John Bell received 590,631, represented by 39 electoral ballots. By this vote Abraham Lincoln became President. The triumph at the ballot-box was flashed by telegraph over the whole country, form north to south, from east to west. It was answered by defiance from the Slave-Masters, speaking in the name of State Rights and for the sake of Slavery. The declared will of the American people, registered at the ballot-box, was set at nought. The conspiracy of years blazed into day. The National Government, which Alexander H. Stephens characterized as “the best and freest government, the most equal in its rights, the most just in its decisions, the most lenient in its measures, and the most aspiring in its principles to elevate the race of men, that the sun of heaven ever shone upon,” and which Jefferson Davis himself pronounced “the best government which has ever been instituted by man,”—that National Government, thus painted even by its enemies, was spurned. South Carolina jumped forward first in crime; and before the elected President turned his face from the beautiful Western prairies to enter upon his dangerous duties, State after State had undertaken to abandon its place in the Union, Senator after Senator had dropped from his seat, fort after fort had been seized, and the mutterings of war had begun to fill the air, while the actual President, besotted by Slavery, tranquilly witnessed the gigantic treason, as he sat at ease in the Executive Mansion—and did nothing.

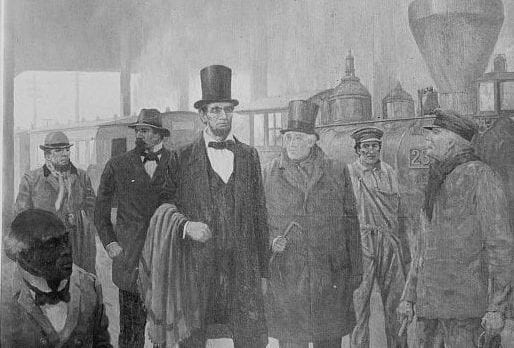

It was time for another to come upon the scene. You cannot forget how he left his village home, never to return, except under the escort of Death. In words of farewell to neighbors thronging about him, he dedicated himself to his country and solemnly invoked the aid of Divine Providence. “I know not,” he said, “how soon I shall see you again”; and then, with prophetic voice, announced that a duty devolved upon him “greater than that which has devolved upon any other man since the days of Washington,” and asked his friends to pray that he might receive that Divine assistance, without which he could not succeed, but with which success was certain. To power and fame others have gone forth with gladness and with song: he went forth prayerfully as to a sacrifice.

Nor can you forget how at each resting-place on the road he renewed his vows, and when at Independence Hall his soul broke forth in homage to the vital truths there declared. Of all that he said on the journey to the national Capital, after farewell to his neighbors, there is nothing so prophetic as these unpremeditated words:—

“All the Political sentiments I entertain have been drawn, so far as I have been able to draw them, from the sentiments which originated in, and were given to the world from, this Hall. I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence.—Now, my friends, can this country be saved upon that basis? If it can, I shall consider myself one of the happiest men in the world, if I can help to save it. If it cannot be saved upon that principle, it will be truly awful. But if this country cannot be saved without giving up that principle, I was about to say I would rather be assassinated on the spot.”

Then, after adding that he had not expected to say a word, he repeated the consecration of his life, exclaiming, “I have said nothing but what I am willing to live by, and if it be the pleasure of Almighty God, to die by.”

He was about to raise the national banner over the old Hall. But before this service, he took up the strain he loved so well, saying: “It is on such an occasion as this that we can reason together, reaffirm our devotion to the country and the principles of the Declaration of Independence.”

Thus constantly did he bear testimony. Surely this grand fidelity will be ever counted among his chief glories. I know nothing in history more touching, especially when we consider that this devotion caused his sacrifice. “Were there as many devils in Worms as there are tiles upon the roofs, I would enter,” said Luther. Our reformer was less defiant, but hardly less determined. Three times had he announced that for the great truths of the Declaration he was willing to die; three times had he offered himself to this martyrdom.

Slavery was already pursuing his life. An attempt was made to throw his train from the track, while a secreted hand-grenade further betrayed the diabolical purpose. Baltimore, directly on his way, was the seat of a murderous plot. Avoiding the conspirators, he came from Philadelphia to Washington unexpectedly in—the night,—and thus, for the moment cheating Assassination of its victim, entered the National Capital.

From this time forward his career broadens into the history of his country and of the age. You all know it. Therefore a few glimpses will be enough, that I may exhibit its moral rather than its story.

The Inaugural Address, the formation of his Cabinet, his earliest acts, his daily conversation, all attested to the spirit of moderation with which he approached his perilous position. At the same time he declared openly, that, in contemplation of universal law and of the Constitution, the Union of these States is perpetual,—that no State, upon its own mere motion, can lawfully get out of the Union,—that resolves and ordinances to that effect are legally void,—that acts of violence within any State are insurrectionary or revolutionary,—and that, to the extent of his ability, he should take care, according to express injunction of the Constitution, that the laws of the Union be faithfully executed in all the States. While thus positive in upholding the National Unity, he was resolved that on his part there should be no act of offence,—and that there should be no bloodshed or violence, unless forced upon the country,—that it was his duty to hold, occupy, and possess the property and places belonging to the Government,—but, beyond what was necessary for this object, there should be no exercise of force, and the people everywhere should be left in that perfect security most favorable to calm thought and reflection.

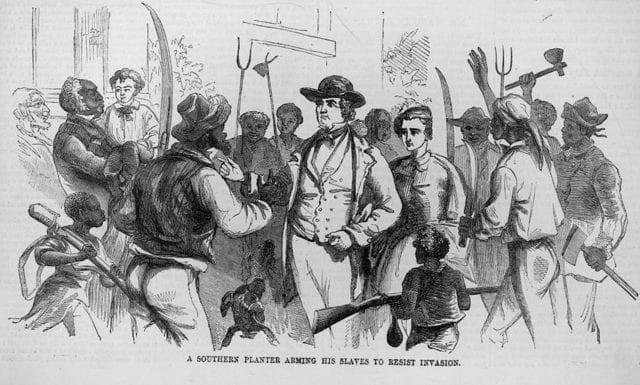

But the madness of Slavery knew no bound. It was determined from the beginning that the Union should be broken, and no moderation could change this wicked purpose. A pretended power was organized, in the form of a Confederacy, with Slavery as the declared corner-stone. You know what ensued. Fort Sumter was attacked, and, after a fiery storm of shot and shell for thirty-four hours, the national flag fell. This was 13th April, 1861. War had begun.

War is always a scourge, and it can never be regarded without sadness. It is one of the mysteries of Providence, that it is still allowed to vex mankind. Few deprecated it more than the President. From Quaker blood and from reflection, he was essentially a man of peace. In one of his speeches during his short service in Congress, he arraigned military glory as “that rainbow that rises in showers of blood,—that serpent’s eye that charms but to destroy”; and when charged with the terrible responsibility of Government, he was none the less earnest for peace. He was not willing to see his beloved country torn by bloody battle, with fellow-citizens striking at each other. But after the criminal assault on Fort Sumter there was no alternative. The Republic was in peril, and every man, from President to citizen, was summoned to the defence. Nor was this all. An attempt was made to invest Slavery with national independence, and the President, who disliked both Slavery and War, described his own condition, when, addressing a member of the Society of Friends, he said, “Your people have had, and are having, very great trials. On principle and faith opposed to both war and oppression, they can only practically oppose oppression by war.” In these few words the whole case is stated,—inasmuch as, whatever might be the pretension of State Rights, the war became necessary to put down the hideous ambition of Slavery.

The Slave-Masters put in execution a conspiracy long contrived, for which they had prepared the way,—first, by teaching that any State might at its own will break from the Union, and, secondly, by teaching that colored persons were so far inferior as not to be embraced in the promises of the Declaration of Independence, but were justly held as slaves. The Mephistopheles of Slavery, Mr. Calhoun, inculcated for years both these pretensions. But the pretension of State Rights was merely a cover for Slavery.

Therefore, in determining that the Slave-Masters should be encountered, two things were resolved: first, that this Republic is one and indivisible; and, secondly, that no hideous power, with Slavery blazoned on its front, shall be created on our soil. Here was affirmation and denial: first, affirmation of the National Unity; and, secondly, denial of any independent foothold to Rebel Slavery. Accepting the challenge at Fort Sumter, the President became the voice of the Nation, which, with stern resolve, insisted that the Rebellion should be overcome by war. The people were in earnest, and would not brook hesitation. If ever in history war was necessary, if ever in history war was holy, it was the war then and there begun for the arrest and overthrow of Rebel Slavery.

The case between the two sides is stated first in the words of Jefferson Davis, and then in the words of Abraham Lincoln. The representative of Slavery said:—

“The time for compromise has now passed, and the South is determined to maintain her position, and make all who oppose her smell Southern powder and feel Southern steel, if coercion is persisted in.—Our separation from the old Union is now complete. No compromise, no reconstruction, is now to be entertained.”

Abraham Lincoln said:–

In my view of the present aspect of affairs, there need be no bloodshed or war. I am not in favor of such a course; and I may say in advance that there will be no bloodshed, unless it be forced upon the Government, and then it will be compelled to act in self-defence.”

And so issue was joined.

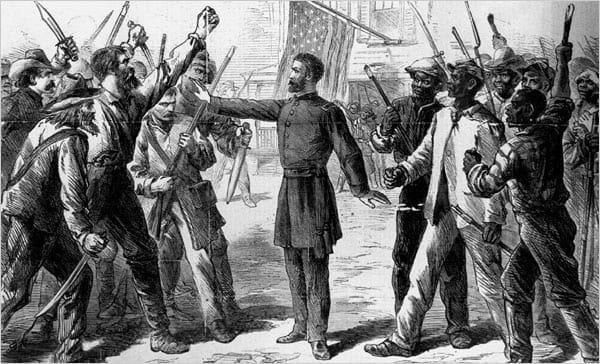

It was plain from the first cannon-shot that the Rebellion was nothing but Slavery in arms; but such was the power of Slavery, even in the Free States, that months elapsed before the giant criminal was directly assailed. Generals in the field were tender towards it, as if it were a church, or a work of the fine arts. Only under the teaching of disaster was the country moved. The first step in Congress followed the defeat at Bull Run. Still the President hesitated. Disasters thickened and graves opened, until at last the country saw that by justice only could we hope for Divine favor, and the President, who leaned so closely upon the popular heart, pronounced that great word by which slaves were set free. Let it be named forever to his glory, that even tardily he grasped the thunderbolt under which the Rebellion staggered to its fall; that, following up the blow, he enlisted colored citizens as soldiers, and declared his final purpose never to retract or modify the Emancipation Proclamation, nor to return into Slavery any person free by the terms of that instrument, or by any Act of Congress,—saying, grandly, “If the people should, by whatever mode or means, make it an Executive duty to reenslave such persons, another, and not I, must be their instrument to perform it.”

It was sometimes said that the Proclamation was of doubtful constitutionality. If this criticism did not proceed from sympathy with Slavery, it evidently proceeded from prevailing superstition with regard to this idol. Future jurists will read with astonishment that such a flagrant wrong could be considered at any time as having any rights which a court was bound to respect, and especially that rebels in arms could be considered as having any title to the services of people whose allegiance was primarily due to the United States. But, turning from these conclusions, it seems obvious that Slavery, standing exclusively on local law, without support in natural law, must have fallen with the local government, both legally and constitutionally: legally, inasmuch as it ceased to have any valid legal support; and constitutionally, inasmuch as it came at once within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Constitution, where Liberty is the supreme law. The President did not act upon these principles, but, speaking with the voice of authority, said, “Let the slaves be free.” What Court and Congress hesitated to declare he proclaimed, and thus enrolled himself among the world’s Emancipators.

From the Proclamation of Emancipation, placing its author so far above human approach that human envy cannot reach him, I carry you for one moment to our Foreign Relations. The convulsion here was felt in the most distant places,—as at the great earthquake of Lisbon, when that capital seemed about to be submerged, there was commotion of the waters in our Northern lakes. All Europe was stirred. There, too, was the Slavery question in another form. In an unhappy moment, under an ill-considered allegation of “necessity,”—which Milton tells us was the plea by which the Fiend “excused his devilish deeds,”—England accorded to Rebel Slavery the rights of belligerence on the ocean, and then proceeded to open her ports, to surrender her workshops, and to let loose her merchant ships in aid of this wickedness: forgetting all relations of alliance and amity with the United States, forgetting all distinctions of right and wrong, and forgetting, also, that a New Power founded on Slavery was a moral monster, with which a just nation could have nothing to do. To appreciate the character of this concession, we must comprehend clearly the whole, vast, unprecedented crime of the Rebellion, taking its complexion from Slavery. Undoubtedly it was criminal to assail the Unity of this Republic, and thus destroy its peace and impair its example in the world; but the attempt to build a New Power on Slavery as a corner-stone, and with no other declared object of separate existence, was more than criminal,—or rather it was a crime of that untold, unspeakable guilt, which no language can depict and no judgment can be too swift to condemn. The associates in this terrible apostasy might rebuke each other in the words of an old dramatist:—

“Thou must do, then,

What no malevolent star will dare to look on,

It is so wicked; for which men will curse thee

For being the instrument, and the blest angels

Forsake me at my need for being the author;

For’t is a deed of night, of night, Francisco!

In which the memory of all good actions

We can pretend to shall be buried quick;

Or, if we be remembered, it shall be

To fright posterity by our example,

That have outgone all precedents of villains

That were before us.”

Recognizing such a power, entering into semi-alliance with such a power, investing such a power with rights, opening ports to such a power, surrendering workshops to such a power, building ships for such a power, driving a busy commerce with such a power,—all this, or any part of this, is positive and plain complicity with the original guilt, and must be judged as we judge any other complicity with Slavery. To say that it was a necessity is only to repeat the perpetual plea by which slave-masters and slave-traders from the earliest moment have sought to vindicate their crime. A generous Englishman, the ornament of letters, from whom we learn in memorable lines “what constitutes a State,” has denounced all complicity with Slavery in words which strike directly at this plea of necessity. “Let sugar be as dear as it may,” wrote Sir William Jones to the freeholders of Middlesex, “it is better to eat none,—to eat honey, if sweetness only be palatable,—better to eat aloes or coloquintida, than violate a primary law of Nature impressed on every heart not imbruted by avarice, than rob one human creature of these eternal rights of which no law upon earth can justly deprive him.”

England led in concession of belligerent rights to Rebel Slavery. No event of the Bebellion compares with this, in encouragement to transcendent crime, or in prejudice to the United States. Out of English ports and English workshops Rebel Slavery drew its supplies. In English ship-yards the cruisers of Rebel Slavery were built and equipped. From English foundries and arsenals Rebel Slavery was armed. And all this was made easy, when her Majesty’s Government, under pretence of an impossible neutrality, lifted Rebel Slavery to equality with the National Government, and gave to it belligerent power on the ocean. The early legend was verified. King Arthur was without sword, when suddenly one appeared, thrust out from a lake. “Lo!” said Merlin the enchanter, “yonder is that sword I spake of: it belongeth to the Lady of the Lake, and if she will, thou mayest take it; but if she will not, it will not be in thy power to take it.” And the Lady of the Lake yielded the sword, so says the legend, even as England yielded the sword to Rebel Slavery.

The President saw the painful consequence of this concession, and especially that it was the first step towards acknowledgment of Rebel Slavery as an Independent Power. Clearly, if it were proper for a foreign power to acknowledge Belligerence, it might, at a later stage, be proper to acknowledge Independence; and any objection vital to Independence would, if applicable, be equally vital to Belligerence. Solemn resolutions of Congress on this question were communicated to foreign powers; but the unanswerable argument against any possible recognition of a New Power founded on Slavery, whether Independent or Belligerent, was stated by the President in a paper which I hold in my hand, and which has never before seen the light. It is a copy of a resolution drawn by himself, which he consigned to me, in his own autograph, for transmission to one of our valued friends abroad, as an expression of opinion on the great question involved, and a guide to public duty.

“Whereas, while heretofore states and nations have tolerated Slavery recently, for the first [time] in the world, an attempt has been made to construct a New Nation upon the basis of Human Slavery, and with the primary and fundamental object to maintain, enlarge, and perpetuate the same: Therefore

Resolved, That no such embryo state should ever be recognized by or admitted into the family of Christian and civilized nations, and that all Christian and civilized men everywhere should by all lawful means resist to the utmost such recognition or admission.”

You will see how distinctly any recognition of Rebel Slavery as an Independent Power is branded, and how “all Christian and civilized men everywhere” are summoned to “resist to the utmost such recognition”; and precisely for the same reason such “Christian and civilized men everywhere” should have resisted to the utmost any recognition of Rebel Slavery as a Belligerent Power. Had this benign spirit entered into the counsels of England when Slavery first took arms, this great historic nation would have shrunk at all hazard from that fatal concession, in itself a plain contribution to Slavery, and opening the way to infinite contributions, without which the criminal pretender must have speedily succumbed. There would have been no plea of “necessity.” But Divine Providence willed it otherwise. Perhaps it was essential to the full revelation of its boundless capacities, that the Republic should stand forth alone, in sublime solitude, warring for Human Rights, and thus become an example to mankind.

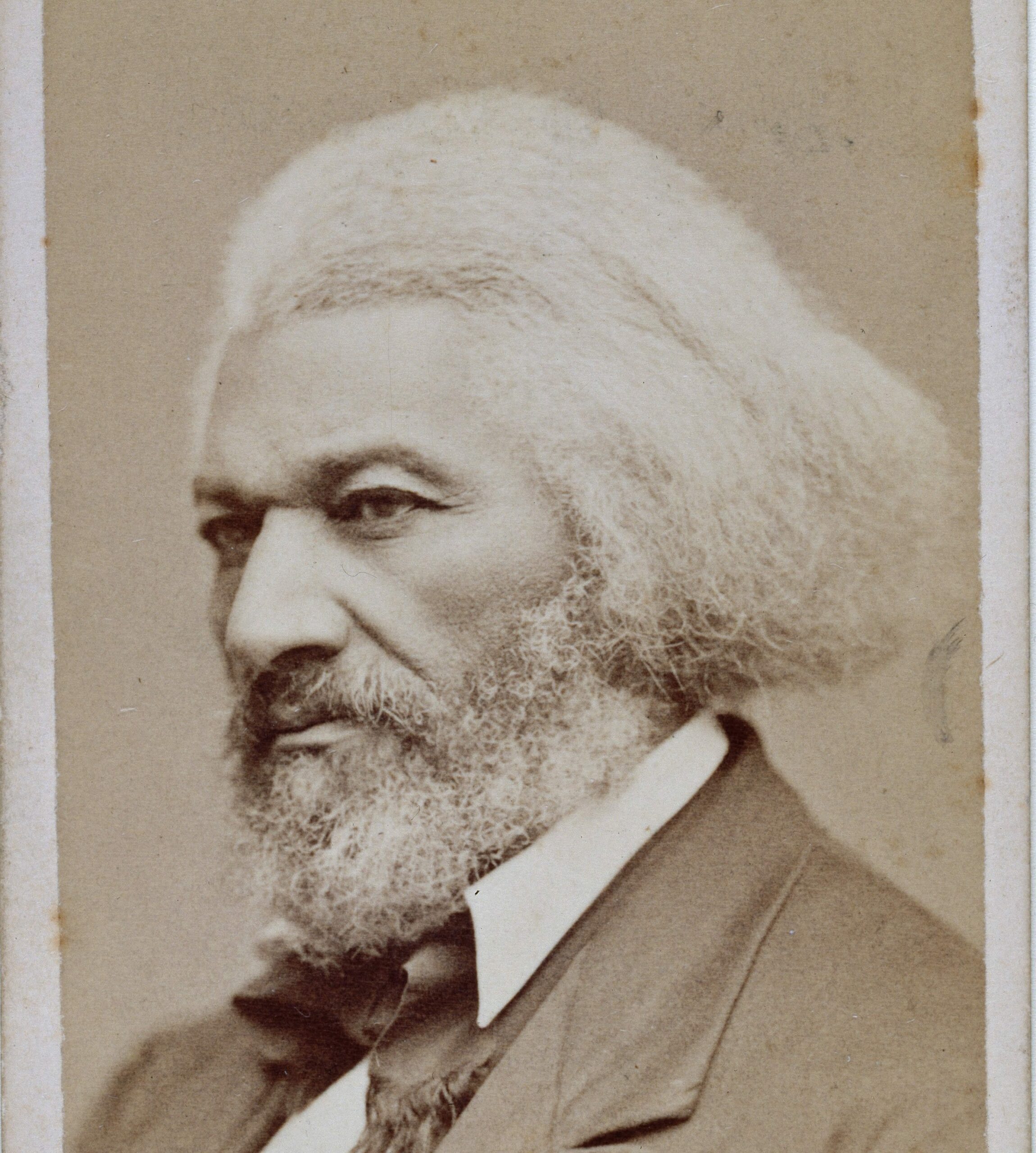

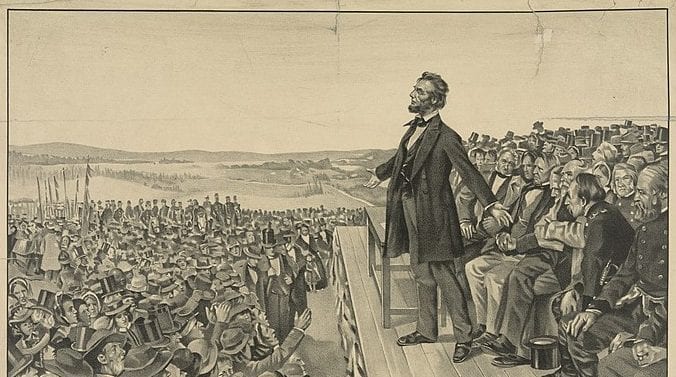

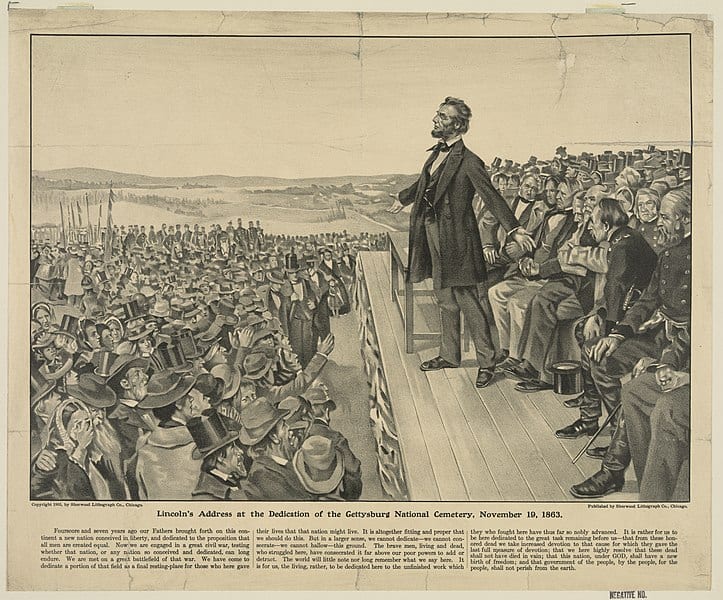

Meanwhile the war continued with proverbial vicissitudes of this arbitrament. Battles were fought and lost. Other battles were fought and won. Rebel Slavery stood face to face in deadly conflict with the Declaration of Independence, when the President, with unconscious power, dealt another blow, second only to the Proclamation of Emancipation. This was at the blood-soaked field of Gettysburg, where the armies of the Republic encountered the armies of Slavery, and, after a conflict of three days, drove them back with destructive slaughter,—as at that decisive battle of Tours, on which hung the destinies of Christianity in Western Europe, the invading Mahometans, after prolonged conflict, were driven back by Charles “the Hammer.” No battle of the present war was more important. Few battles in history compare with it. A few months later, there was another meeting on that same field. It was of grateful fellow-citizens, gathered from all parts of the Union to dedicate it to the memory of those who had fallen there. Eminent men of our own country and from foreign lands united in the service. There, too, was your classic orator, whose finished address was a model of literary excellence. The President spoke very briefly; but his few words will live as long as Time. Since Simonides wrote the epitaph for those who died at Thermopylae, nothing equal has ever been breathed over the fallen dead. Thus he began: “Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth upon this continent a New Nation, conceived in Liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” How grandly, and yet simply, is the New Nation announced, with the Equality of All Men as its frontlet! The truths of the Declaration, so often proclaimed by him, and for which he was willing to die, are inscribed on the altar of the slain, while the country is summoned to their support, that our duty may not be left undone.

It is for us, the living, rather to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us; that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion; that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain; that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of Freedom; and that government of the people, by the people, and for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

That speech, uttered at the field of Gettysburg, and now sanctified by the martyrdom of its author, is a monumental act. In the modesty of his nature, he said: “The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here; but it can never forget what they did here.” He was mistaken. The world noted at once what he said, and will never cease to remember it. The battle itself was less important than the speech. Ideas are more than battles.

Among events assuring to him the general confidence against all party clamor and prejudice, this speech cannot be placed too high. To some who doubted his earnestness it was touching proof of their error. Others who followed with indifference were warmed with grateful sympathy. Many felt its exquisite genius, as well as lofty character. There were none to criticize.

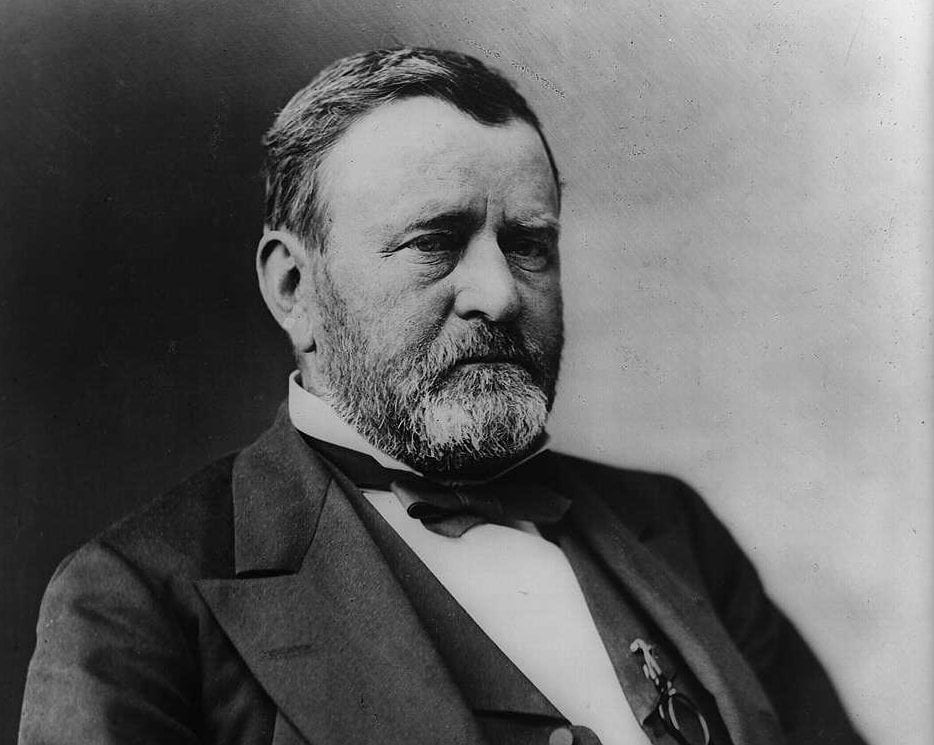

His reelection was not only a personal triumph, but a triumph of the Republic. For himself personally, it was much to find his administration ratified; but for republican ideas it was of incalculable value that at such a time the plume of the soldier had not prevailed. In the midst of war, the people at the ballot-box deliberately selected the civilian. Ye who doubt the destinies of the Republic, who fear the ambition of a military chief, or suspect the popular will, do not forget that at this moment, when the noise of battle filled the whole land, the country quietly appointed for its ruler this man of peace.

The Inaugural Address which signalized his entry for a second time upon his great duties was briefer than any in our history; but it has already gone further, and it will live longer, than any other. It was a continuation of the Gettysburg speech, with the same sublimity and gentleness. Its concluding words were like an angelic benediction.

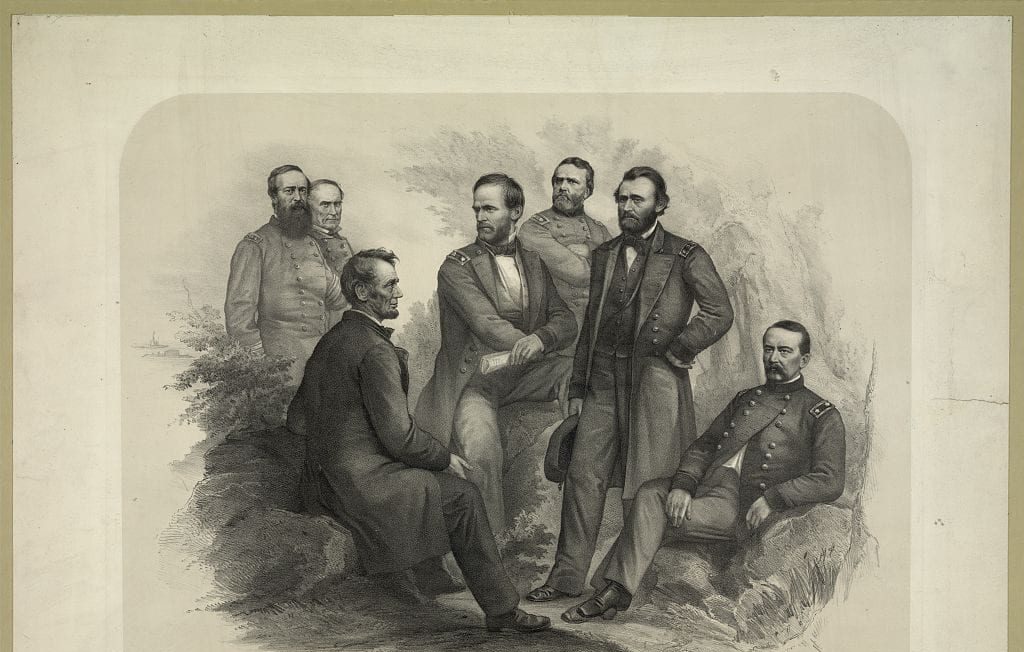

And now there was surfeit of battle and of victory. Calmly he saw the land of Slavery enveloped by the national forces,—saw the great coil bent by his generals about it,—saw the mighty garrote, as it tightened against the neck of the Rebellion. Good news came from all quarters. Everywhere the army was doing its duty. One was conquering in Tennessee; another was watching at Richmond. The navy echoed back the thunders of the army. Place after place was falling,—Savannah, Charleston, Fort Fisher, Wilmington. The President left the National Capital to be near the Lieutenant-General. Then came the capture of Petersburg and Richmond, with the flight of Jefferson Davis and his Cabinet. Without pomp or military escort, the President entered the Capital of the Rebellion, and walked its streets, from which slavery had fled forever. Then came the surrender of Lee; that of Johnston was at hand. The military power of Rebel Slavery was broken like a Prince-Rupert’s drop, and everywhere within its confines the barbarous government tumbled in crash and ruin. The country was in ecstasy. All this he beheld without elation, while his soul was brooding on thoughts of peace and clemency. On the morning of Friday, 14th April, his youthful son, who had been on the staff of the Lieutenant-General, returned to resume his interrupted studies. The father was happy in the sound of his footsteps, and felt the augury of peace. During the same day the Lieutenant-General returned. In the intimacy of his family the President said, “This day the war is over.” In the evening he sought relaxation, and you know the rest. Alas! The war was not over. The minions of Slavery were dogging him with unabated animosity, and that night he became a martyr.

The country rose at once in agony of grief, and everywhere strong men wept. City, town, and village were darkened by the general obsequies. Every street was draped. Only ensigns of woe were seen. He had become, as it were, the inmate of every house, and the families of the land were in mourning. Not in the Executive mansion only, but in uncounted homes, was his vacant chair. Never before such universal sorrow. Already the voice of lamentation is returning from Europe, where candor towards him had begun even before his tragical death. A short time ago he was unknown, except in his own State. A short time ago he visited New York as a stranger, and was shown about its streets by youthful companions. Five years later he was borne through those streets with funeral pomp such as the world never witnessed before. Space and speed were forgotten in the offering of hearts. As the surpassing pageant, with more than “sceptred pall,” moved on iron highways, over Counties and States, from ocean-side to prairie, the whole afflicted people bowed their uncovered heads.

At the first moment it was hard to comprehend this blow, and many cried in despair. But the rule of God has been too visible of late to allow doubt of His constant presence. Did not our martyr in his last address remind us that the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether? And who will say that his death was not a judgment of the Lord? Perhaps it was needed to lift the country into a more perfect justice and to inspire a sublime faith. Perhaps it was sent in love, to set a sacred, irreversible seal upon the good he had done, and to put Emancipation beyond all mortal question. Perhaps it was the sacrificial consecration of those primal truths embodied in the birthday Declaration of the Republic, which he had so often vindicated, and for which he had announced his willingness to die.

He is gone, and he has been mourned sincerely. Only private sorrow would recall the dead. He is now removed beyond earthly vicissitudes. Life and death are both past. He had been happy in life: he was not less happy in death. In death, as in life, he was still under the guardianship of that Divine Providence, which, taking him early by the hand, led him from obscurity to power and fame. The blow was sudden but not unprepared for. Only on the Sunday preceding, as he was coming from the front on board the steamer, with a quarto Shakespeare in his hands, he read aloud the well-remembered words of his favorite “Macbeth”:—

“Duncan is in his grave;

After life’s fitful fever, he sleeps well.

Treason has done his worst; nor steel, nor poison,

Malice domestic, foreign levy, nothing,

Can touch him further.”

Impressed by their beauty, or by some presentment unuttered, he read them aloud a second time. As the friends about listened to his reading, they little thought how in a few days what was said of the murdered Duncan would be said of him. “Nothing can touch him further.” He is saved from the trials that were gathering. He had fought the good fight of Emancipation. He had borne the brunt of war with embattled hosts, and conquered. He had made the name of Republic a triumph and a joy in foreign lands. Now that the strife of blood was ended, it remained to be seen how he could confront those machinations which are only prolongation of the war, and the more dangerous because more subtle,—where recent Rebels, with professions of Union on the lips, but still denying the birthday Declaration of the Republic, vainly seek to organize peace on another Oligarchy of the skin. From all these trials he was saved. But his testimony lives, and will live forever, speaking by his life, quickened by the undying echoes of his tomb. Invisible to mortal sight, and now above all human weakness, he is still champion, as in his early conflict, summoning his countrymen back to the truths in the Declaration of Independence. Dead, he speaks with more than living voice. But the author of Emancipation cannot die. His immortality on earth has begun. Country and age are already enshrined in his example, as if he were the great poet gathered to his fathers.

Back to the living hath he turned him,

And all of the death has passed away;

The age that thought him dead and mourned him

Itself now lives but in his lay.

If the President were on earth, he would protest against any monotony of panegyric. He never exaggerated. He was always cautious in praise, as in censure. In endeavor to estimate his character, we shall be nearer him in proportion as we cultivate the same spirit.

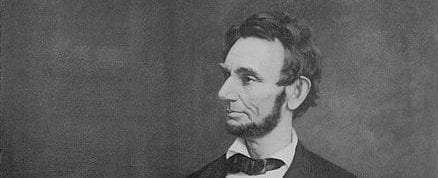

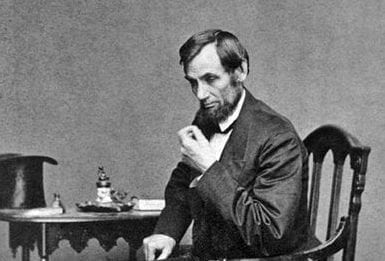

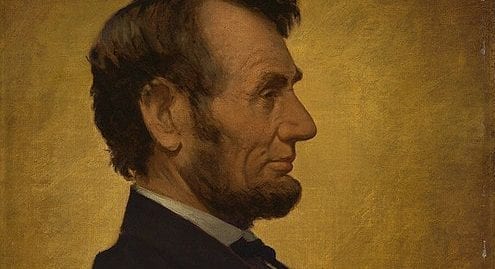

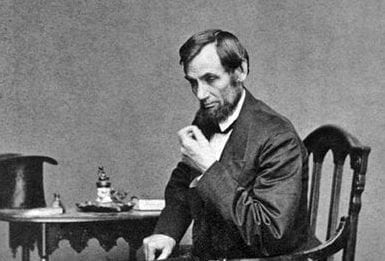

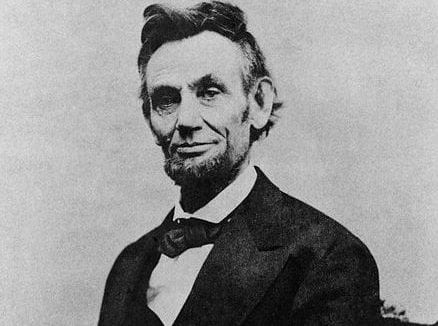

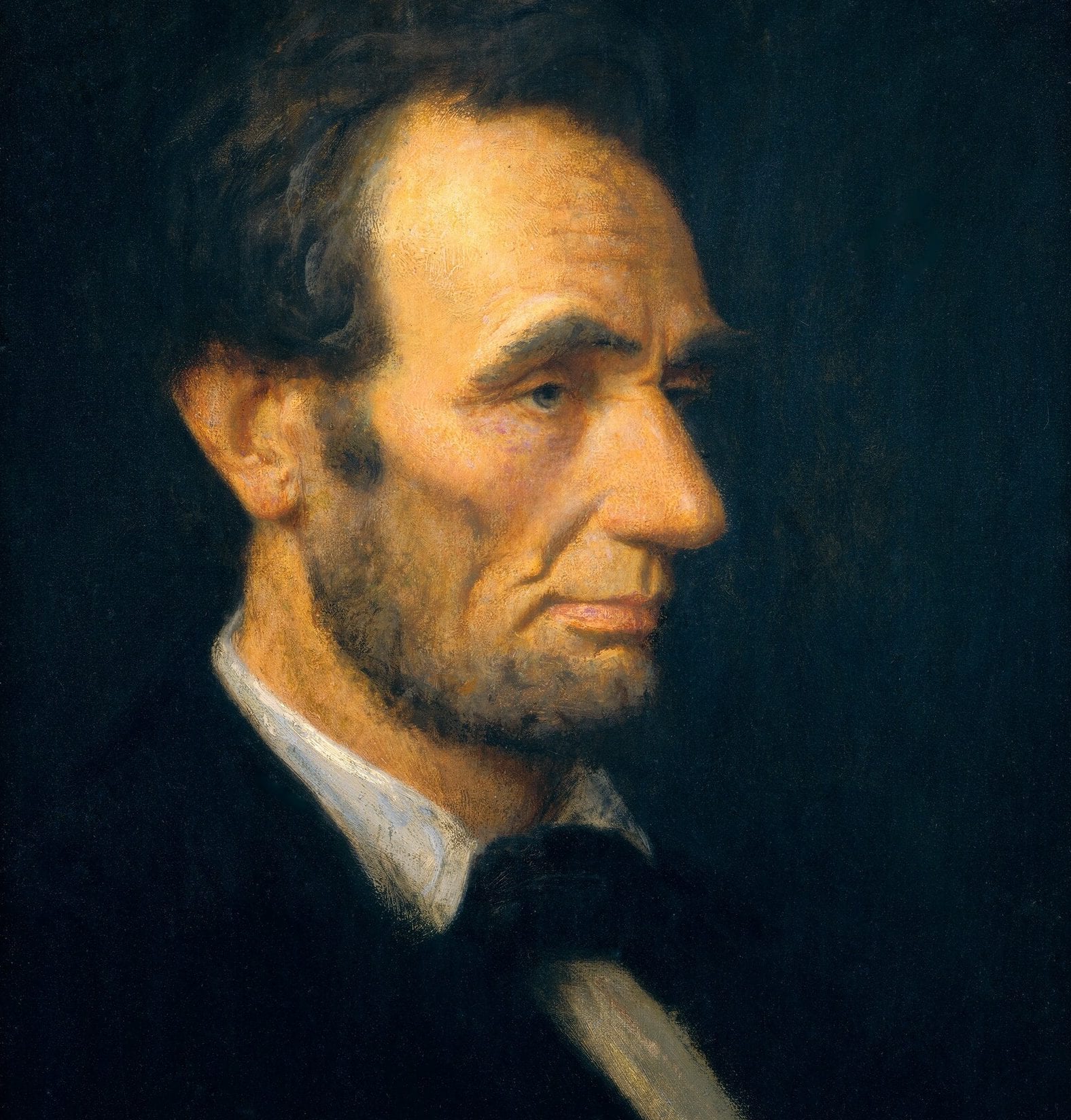

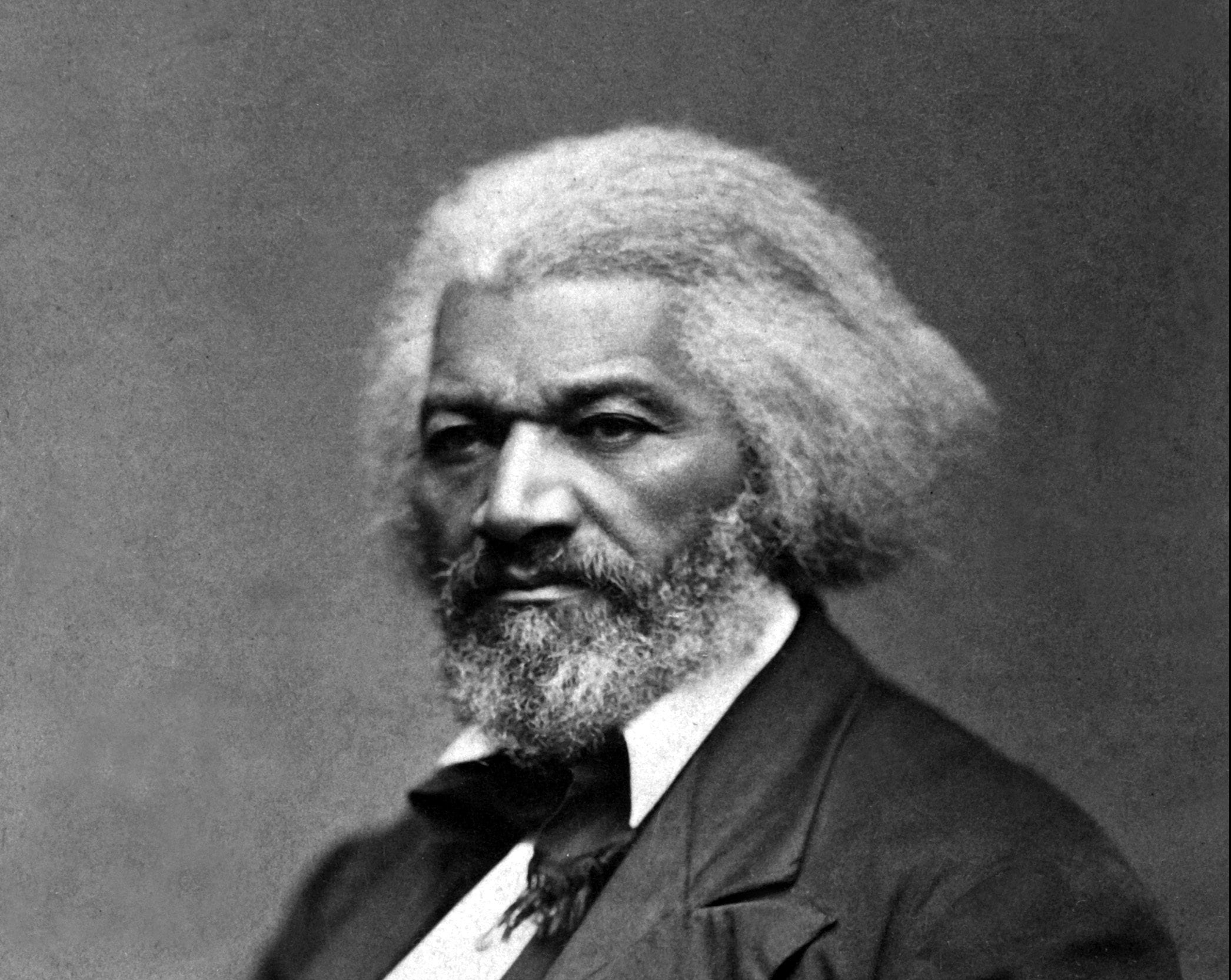

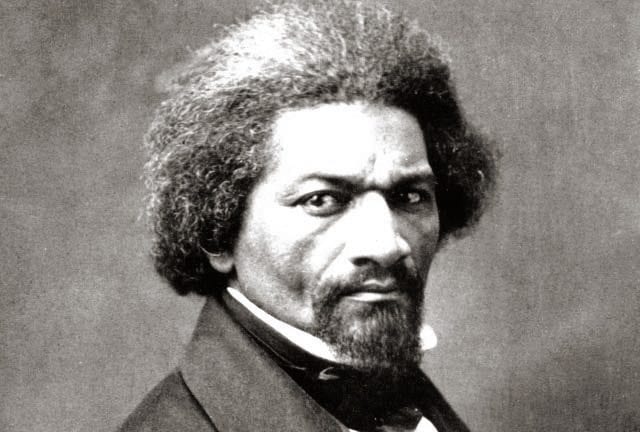

In person he was tall and bony, with little resemblance to any historic portrait, unless he might seem in one respect to justify the epithet given to an early English king. As he stood, his form was angular, with something of that straightness in lines so peculiar in the figure of Dante by Flaxman. His countenance had more of rugged strength than his person, and, while in repose, inclined to sadness; yet it lighted easily. Perhaps the quality that struck most at first was his constant simplicity of manner and conversation, without form or ceremony beyond that among neighbors. His handwriting had the same simplicity. It was clear as that of Washington, but less florid. Each had been surveyor, and was perhaps indebted to this experience. But the son of the Western pioneer was more simple in nature, and the man appeared in the autograph. An integrity which has become a proverb belonged to the same quality. The most perfect honesty must be the most perfect simplicity. Words by which an ancient Roman was described picture him,—”Vita innocentissimus, proposito sanctissimus.” He was naturally humane, inclined to pardon, and never remembered hard things against himself. He was always good to the poor, and in dealings with them was full of those “kind little words which are of the same blood as great and holy deeds.” On the Saturday before his death I saw him shake hands with more than five thousand soldier patients in the tent-hospitals at City Point, and he told me afterwards that his arm was not tired. Such a character awakened the instinctive sympathy of the people. They saw his fellow-feeling, and felt the kinship. With him as President, the idea of Republican Institutions, where no place is too high for the humblest, was perpetually apparent; so that his simple presence was like a Proclamation of the Equality of all men.

While social in nature and enjoying the flow of conversation, he was often reticent. Modesty was natural to such a character. Without affectation, so was he without pretension or jealousy. No person, civil or military, complains that he appropriated to himself any honor belonging to another. To each and all he gave the credit that was due. And this same spirit appeared in smaller things. In a sally of Congressional debate, he exclaimed, that a fiery slave-master of Georgia, who had just spoken, was “an eloquent man, and a man of learning, so far as he could judge, not being learned himself.” (Congress. Globe, Appendix, 1st Session, 30th Congress, p. 1042)

His humor, like his integrity, has become a proverb. Sometimes he insisted that he had no invention, but only memory. Good things heard he did not forget, and he was never without a familiar story. When he spoke, the recent West seemed to vie with the ancient East in apologue and fable. His ideas moved, as the beasts entered Noah’s ark, in pairs. His illustrations had a homely felicity, and seemed not less important to him than the argument, which he always enforced with a certain emphasis of manner and voice. This same humor was often displayed where there was no story, and with a point that might recall Franklin. I know not how the indifference to Slavery exhibited by so many could be exposed more effectively than when he said of a political antagonist thus offending, “I suppose the institution of Slavery really looks small to him. He is so put up by nature, that a lash upon his back would hurt him, but a lash upon anybody else’s back does not hurt him.” And then again there is a bit of reply to Mr. Douglas, most characteristic not only for humor, but as showing how little at that time he was looking to the great place he reached so soon afterwards. “Senator Douglas,” said he, “is of world-wide renown. All the anxious politicians of his party, or who have been of his party for years past, have been looking upon him as certainly, at no distant day, to be the President of the United States. They have seen in his round, jolly, fruitful face post-offices, land-offices, marshalships and cabinet appointments, chargéships and foreign missions, bursting and sprouting out in wonderful exuberance, ready to be laid hold of by their greedy hands. . . . On the contrary, nobody has ever expected me to be President. In my poor, lean, lank, face nobody has ever seen that any cabbages were sprouting out. These are disadvantages, all taken together, that the Republicans labor under. We have to fight this battle upon principle, and upon principle alone.” Here is a glimpse of himself, as honorable as curious. In a different vein, he said, while President, “The United States Government must not undertake to run the churches.” Here wisdom and humor vie with each other.

He was original in mind as in character. His style was his own, having no model, but springing directly from himself. Failing often in correctness, it is sometimes unique in beauty and sentiment. There are passages which will live always. It is no exaggeration to say, that, in weight and pith, suffused in a certain poetical color, they call to mind Bacon’s Essays. Such passages make an epoch in State Papers. No presidential message or speech from a throne ever had anything of such touching reality. They are harbingers of the great era of Humanity. While uttered from the heights of power, the reveal a simple, unaffected trust in Almighty God, and speak to the people as equal to equal.

He was placed by Providence at the head of his country during an unprecedented crisis, when the fountains of the great deep were broken up, and men turned for protection to military power. Multitudinous armies were mustered. Great navies were created. Of all these he was constitutional commander-in-chief. As the war proceeded, prerogatives enlarged and others sprang into being, until the sway of a Republican President became imperatorial, imperial. But not for one moment did the modesty of his nature desert him. His constant thought was his country, and how to serve it. He saw the certain greatness of the Republic, and was pleased in looking forward to that early day, when, according to assured calculation, its millions of people will count by the hundred; but he saw in this prodigious sway nothing but the good of man. Personal ambition at the expense of patriotism was as far removed from the simple purity of his nature as poison from a strawberry. And thus, with equal courage in the darkest hours, he continued on, heeding as little the warnings of danger as the temptations of power. “It would not do for a President,” he said, “to have guards with drawn sabres at his door, as if he fancied he were, or were trying to be, or were assuming to be, an Emperor.” In the same homeliness he spoke of his morning return to daily duty as “opening shop.” Though commissioning officers in multitudes beyond any other person of authentic history, he never learned the mystery of shoulder-straps or of buttons in the military and naval uniforms, except that he noticed three stars on the shoulders of the Lieutenant-General.

When he became President, he was without any considerable experience in public affairs; nor was he much versed in history, whose lessons would have been valuable. Becoming more familiar with the place, his facility increased. He had “learned the ropes,” so he said. But his habits of business were irregular, and never those of dispatch. He did not see at once the just proportions of things, and allowed himself to be too much occupied by details. Even in small affairs, as well as great, there was in him a certain resistance to be overcome. There were moments when this delay caused impatience, and important questions seemed to suffer. But when the blow fell, there was nothing but gratitude, and all confessed the singleness with which he sought the public good. A conviction prevailed, that, though slow to reach his conclusion, he was inflexible in maintaining it. Pompey boasted that by the stamp of his foot he could raise an army. The President did this by a word, and more: according to his own saying, he “put his foot down,” and saved a principle.

This firmness in the right, as he saw it, was an anchor which held always. Emancipation, once adopted, was safe against recall or change. From time to time his determination was repeated in terms which awakened a throb in every liberty-loving bosom,—as when, in the summer before the Presidential election, in his letter “To whom it may concern,” he announced “the abandonment of Slavery” as an essential condition for peace, and thus again proclaimed Emancipation,—or when, on another occasion, he said, in simple words, “And the promise, being made, must be kept,”—and then again exclaimed, loftily, in words good to repeat, “If the people should, by whatever mode or means, make it an Executive duty to reenslave such persons, another, and not I, must be their instrument to perform it.” All this was beautiful and grand. Sodom was burning, but there was no disposition to look back.

In statement of moral truth and exposure of wrong he was at times singularly cogent. There was fire as well as light in his words. Nobody more clearly exhibited Slavery in is enormity. On one occasion, he branded it as a “monstrous injustice”; on another, he pictured the slave-masters as “wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces”; and then, on still another, he said, with fine simplicity of diction, “If Slavery is not wrong, then nothing is wrong.” Would you find condemnation more complete, you must go to John Brown, or to those famous words of John Wesley, where the great Methodist held up slavery as the “execrable sum of all villanies.” Another mind, more submissive to the truth he recognized, and less disposed to take counsel of to-morrow, would have hesitated less in carrying this judgment forward to its natural conclusion. Perhaps, his courage to apply truth was not always equal to his clearness in seeing it. Perhaps, the heights that he gained in conscience were not always sustained in conduct. And have we not been told that the soul can gain heights it cannot keep? Thus, while condemning Slavery, he still waited, till many feared that with him judgment would “lose the name of action.” Even while exalting Human Equality, assailed and derided by one of our ablest debaters, and insisting, with admirable constancy, that all, without distinction of color, are within the birthday promises of the Republic, he yet allowed himself to be pressed by his adversary to an illogical limitation of this self-evident truth, so that colored persons might be excluded from political rights. But he was willing at all times to learn, and not ashamed to change. Before death he expressed a desire that suffrage should be accorded to colored persons in certain cases; yet here again he failed to apply the great Declaration for which he so often contended. If suffrage be accorded to colored persons only in certain cases, then, of course, it can be accorded to whites only in the same cases,—or Equality ceases to exist.

It was his own frank confession that he had not controlled events, but they had controlled him. At the important stages of the war, he followed rather than led. The people, under God, were masters. Let it not be forgotten that the national triumphs, and even Emancipation itself, sprang from the great heart of the American people. Individual services have been important, but there is no man who has been necessary.