No related resources

Introduction

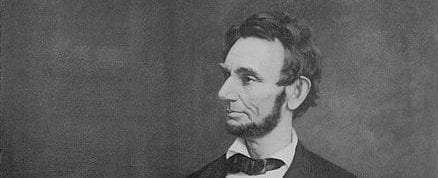

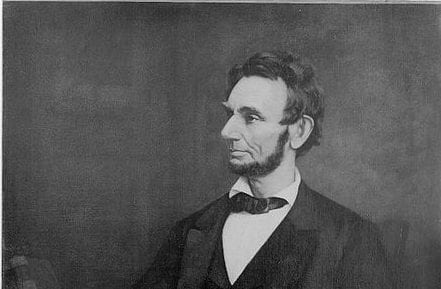

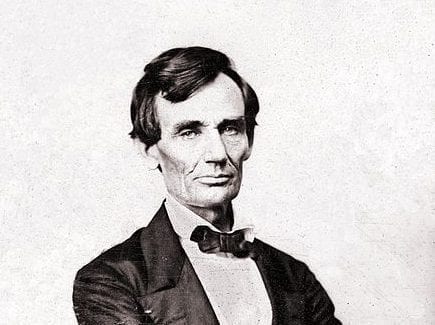

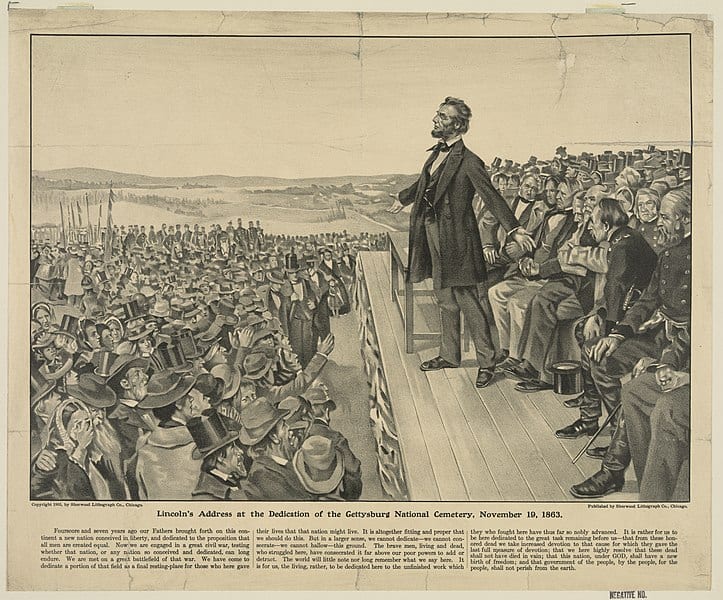

In this letter to newspaper editor Albert Hodges, Lincoln explains his actions with respect to slavery and the Constitution. Lincoln specifically justifies the Emancipation Proclamation on grounds of military necessity, not his moral opposition to slavery. As he did in a special message of July 4, 1861 (Message to Congress in Special Session (1861)), Lincoln points to the oath of office as a source of authority to preserve the nation.

Unlike Thomas Jefferson, who did not defend the Louisiana Purchase as constitutional, Lincoln reads the Constitution to be different during times of emergency. Lincoln’s letter to Hodges should be compared to Jefferson’s letter to Colvin (Letter to John B. Colvin (1810)). Whereas Lincoln grounds the source of his authority in the president’s oath of office, Jefferson refrains from making a constitutional argument to support his answer to Colvin that there are occasions when an officer in high trust must go beyond the law. Later presidents will appeal to both examples (Nixon, Interview on the Huston Plan (1977)).

Source: Abraham Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln papers: Series 1. General Correspondence. 1833 to 1916: Abraham Lincoln to Albert G. Hodges, April 4, 1864. Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, https://goo.gl/dpkx2e.

My dear Sir: You ask me to put in writing the substance of what I verbally said the other day, in your presence, to Governor Bramlette and Senator Dixon.[1] It was about as follows:

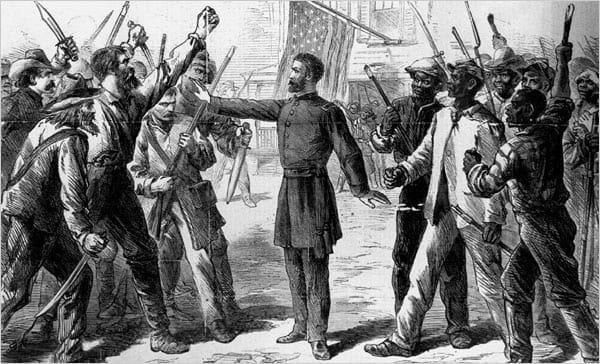

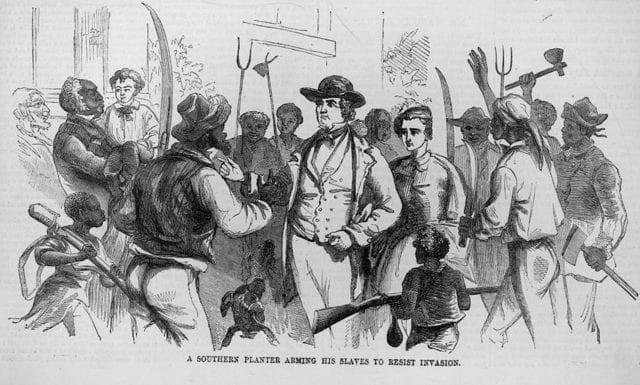

“I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I can not remember when I did not so think, and feel. And yet I have never understood that the Presidency conferred upon me an unrestricted right to act officially upon this judgement and feeling. It was in the oath I took that I would, to the best of my ability, preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States. I could not take the office without taking the oath. Nor was it my view that I might take an oath to get power, and break the oath in using the power. I understood, too, that in ordinary civil administration this oath even forbade me to practically indulge my primary abstract judgement on the moral question of slavery. I had publicly declared this many times, and in many ways. And I aver that, to this day, I have done no official act in mere deference to my primary abstract judgement on the moral question of slavery. I did understand however, that my oath to preserve the Constitution to the best of my ability, imposed upon me the duty of preserving, by every indispensable means, that government – that nation – of which that constitution was the organic law. Was it possible to lose the nation, and yet preserve the Constitution? By general law life and limb must be protected; yet often a limb must be amputated to save a life; but a life is never wisely given to save a limb. I felt that measures, otherwise unconstitutional, might become lawful, by becoming indispensable to the preservation of the Constitution, through the preservation of the nation. Right or wrong, I assumed this ground, and now avow it. I could not feel that, to the best of my ability, I had even tried to preserve the Constitution, if, to save slavery, or any minor matter, I should permit the wreck of government, country, and Constitution all together. When, early in the war, Gen. Fremont[2] attempted military emancipation, I forbade it, because I did not then think it an indispensable necessity. When a little later, Gen. Cameron,[3] then Secretary of War, suggested the arming of the blacks, I objected, because I did not yet think it an indispensable necessity. When, still later, Gen. Hunter[4] attempted military emancipation, I again forbade it, because I did not yet think the indispensable necessity had come. When, in March, and May, and July 1862 I made earnest, and successive appeals to the border states to favor compensated emancipation, I believed that the indispensable necessity for military emancipation, and arming the blacks would come, unless averted by that measure. They declined the proposition; and I was, in my best judgment, driven to the alternative of either surrendering the Union, and with it, the Constitution, or of laying [a] strong hand upon the colored element. I chose the latter. In choosing it, I hoped for greater gain than loss; but of this, I was not entirely confident. More than a year of trial now shows no loss by it in our foreign relations, none in our home popular sentiment, none in our white military force, – no loss by it any how or anywhere. On the contrary, it shows a gain of quite a hundred and thirty thousand soldiers, seamen, and laborers. These are palpable facts, about which, as facts, there can be no caviling. We have the men; and we could not have had them without the measure.

“And now let any Union man who complains of the measure, test himself by writing down in one line that he is for subduing the rebellion by force of arms; and in the next, that he is for taking these hundred and thirty thousand men from the Union side, and placing them where they would be but for the measure he condemns. If he cannot face his case so stated, it is only because he cannot face the truth.”

I add a word which was not in the verbal conversation. In telling this tale I attempt no compliment to my own sagacity. I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me. Now, at the end of three years’ struggle the nation’s condition is not what either party, or any man devised, or expected. God alone can claim it. Whither it is tending seems plain. If God now wills the removal of a great wrong, and wills also that we of the North as well as you of the South, shall pay fairly for our complicity in that wrong, impartial history will find therein new cause to attest and revere the justice and goodness of God.

Yours truly,

A. Lincoln

- 1. Governor Thomas E. Bramlette, (1817 – 1875) served as the governor of Kentucky from 1863 – 1867. A Union Democrat, he supported the war and President Lincoln until the army began recruiting black men to serve. Archibald Dixon (1802 – 1876) served as senator from Kentucky from 1852 – 1855, and remained active in the state’s politics through the Civil War era, advocating for policies that were both pro-slavery and pro-Union.

- 2. John Charles Fremont (1813 – 1890) served as a Union general in the West; Lincoln not only superceded his emancipation order, he relieved Fremont of command as a result of it.

- 3. Simon Cameron (1799 – 1889) served as United States Secretary of War under Lincoln at the start of the Civil War, a post at which he failed abysmally; he was forced to resign under a cloud of corruption charges that resulted in a congressional censure.

- 4. David Hunter (1802 – 1886), an outspoken abolitionist, served as a Union general. In May 1862, as commander of the Department of the South, he issued General Order No. 11, emancipating the slaves in Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida.

Address at a Sanitary Fair

April 18, 1864

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.