Slavery and Its Consequences—A New Core Document Collection

Slavery and its Consequences was recently released in Teaching American History’s Core Document Collection. We talked with the volume’s editor, David Tucker, to learn what he hopes the collection contributes to the CDC series and to our understanding of the contested history of racial justice in America.

Now a Senior Fellow at Ashbrook and General Editor of the Core Document series, Tucker earned his Ph.D. in American history at Claremont Graduate School, afterwards working both in the Pentagon and overseas for the US government. He also taught for fifteen years at the Naval Postgraduate School, while authoring books and articles on American history and US military policy. These include Enlightened Republicanism (Lexington Books, 2007), a study of Thomas Jefferson’s only book-length work, Notes on the State of Virginia; the second edition of United States Special Operations Forces (Columbia University Press, 2020); and a concise and provocative history of irregular warfare and Euro-American imperialism, Revolution and Resistance: Moral Revolution, Military Might, and the End of Empire (Johns Hopkins, 2016). Tucker, who teaches in our programs, has also edited several CDC volumes, including Westward Expansion (co-edited with Patrick J. Garrity), Documents and Debates in American History and Government, Vol. 2, 1865-2009, and Religion in American History and Politics (with Sarah Morgan Smith and Ellen Tucker).

You call this collection Slavery and its Consequences. It’s the first volume in the series that examines the consequences of a now defunct American practice. Why is such a volume needed?

Nothing else in American history has had such wide-ranging consequences. It caused the Civil War, which changed America profoundly. Questions relating to race in America still dominate our politics. In large measure, we are still dealing with issues that arose after emancipation and were not resolved during Reconstruction. The Fourteenth Amendment was passed to deal with the issues of emancipation and that amendment over time changed the character of American citizenship, making it national, and changing citizens’ relation with the Federal government.

Would you explain the principle that guided your document selections?

I chose documents to emphasize not the suffering slavery caused—which was considerable, obviously—but the perseverance of African Americans in the face of suffering. Those enslaved never completely submitted. It is striking how often slaves took advantage of even the smallest opportunity to negotiate with masters and extract concessions. There was all sorts of resistance and it continued after emancipation when African Americans were treated unjustly.

Slavery did not destroy African Americans’ hopes and potential. As soon as they were freed, African Americans got to work building their lives, taking up trades, farming, and building schools and churches for themselves and their children. They made remarkable efforts to gain education. They also began acquiring property. The proportion of African Americans owning farms increased in the forty years after 1870, while it decreased among whites. This happened even as Jim Crow laws were enacted to hinder African Americans’ opportunities, and despite acts of violence and terror that robbed some of what they earned. This story is a monument to the strength of the human spirit, and it needs emphasis.

I also wanted to show that slavery did not harm only African Americans. By far, African Americans suffered the most; yet everyone in America was harmed. As the documents show, this was a theme of African American argument against slavery. After slavery, it continued to be an argument against racism. Slavery corrupted the morals of Americans; it also undermined freedom. Before the Civil War, for example, the slave power was eroding civil liberties, restricting the mail, muzzling Congressmen who tried to present anti-slavery petitions, etc.

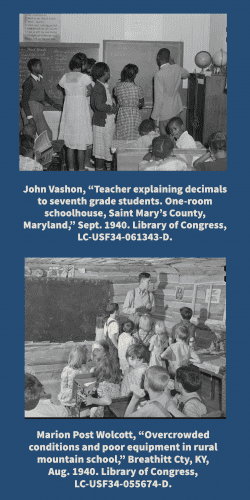

After the Civil War, racist appeals encouraged whites to accept conditions they should not have accepted. Many Southerners put up with terrible schooling for decades because they were persuaded to fear integrated schools. From the viewpoint of an economist, the labor system under Jim Crow was irrational. Despite the potential of African Americans to do a range of jobs, Jim Crow restricted them to sweeping floors, hoeing cotton, and other menial tasks. This retarded economic growth in the South.

You argue in your introduction that compromises at the Constitutional Convention favoring slaveholders were not meant to encourage slavery. Yet racial justice theorists claim the founders deliberately chose slavery to develop the country’s resources.

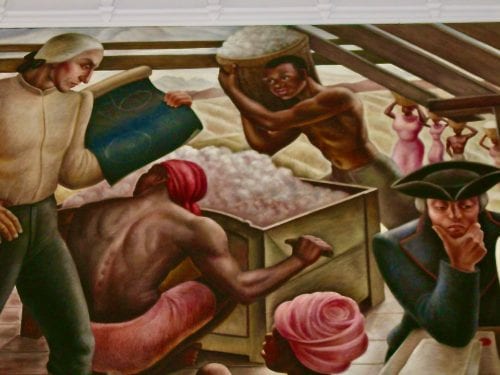

I think that’s false. Slavery came to America through accidents and opportunism; it persisted over objections. Black slave labor was introduced to the colonies in the early 17th century as one source of labor; indentured servants were another. But when economic conditions improved in Britain and the number of indentured servants declined, Southerners turned to slave labor. Some planned from the beginning to use slaves; South Carolina’s first settlers came from Barbados, where there was a well-established slave labor system producing sugar. The South Carolinians used slave labor to cultivate rice and cotton. Northern settlers bought fewer slaves, and opposition to slavery grew in the North. The first document in the collection is a protest against slavery dated 1668, written by Francis Pastorius of Pennsylvania.

Excerpts in this collection from James Madison’s notes of the debates at the Constitutional Convention show delegates speaking against slavery. No one argued that slavery should be encouraged. However, the South Carolinians insisted that their constituents had invested heavily in slavery and would not ratify the Constitution if it undermined the slave system. The delegates made compromises with the slaveholding states in order to get the Constitution adopted.

No one at the time thought the Federal government should have the power to dictate social or economic arrangements in the states, so using the Constitution to abolish slavery wasn’t an option. It is one of the consequences of slavery that we now accept the power of the federal government in so many aspects of American life.

Soon after adoption of the Constitution, Ely Whitney invented the cotton gin, making cotton a hugely profitable export crop. The interest in slavery grew and spread, north as well as south, because northerners spun cotton into cloth and carried it in their ships to England. At the same time, a theory—“polygenesis”—arose: the belief that instead of deriving from a common ancestor, different races of human beings arose in different parts of the world, with some races superior to others. Because this theory contradicted the Biblical account, it wasn’t widely popular, but it was a challenge to the Declaration’s claim that all men were created equal. Eventually John C. Calhoun of South Carolina stood up in the Senate and called the rule of European Americans over African Americans a “positive good.” No one had ever argued this before.

It’s now fashionable to claim that the principles of the Declaration were a lie when they were written. Did Americans believe these principles in 1776?

Yes, they did. First, you have to understand what the statement “All men are created equal” meant. Lincoln said it meant that human beings have rights that other human beings must respect. It didn’t mean we are all born with equal physical or intellectual gifts; we don’t have rights to equal wealth. But no man has the right to live off the sweat of another man’s brow, as Lincoln said. Any system that allows that, whether American slavery or European monarchy, is wrong. In this sense, Americans in 1776 certainly believed in human equality. Their revolution made no sense if the Declaration were untrue. The Declaration said that government required the consent of the governed. But the British Parliament ruled over them without their consent, treating them as slaves, as they themselves wrote.

It’s false to say that because Americans did not abolish slavery in 1776, they could not really have believed in human equality. Jefferson wrote a law to end slavery in Virginia. It wasn’t enacted, but he had no reason to do that if he didn’t believe in the principles of the Declaration. Some northern states did abolish slavery or set gradual emancipation in motion. Many Americans at the time saw no practical way to abolish slavery, except through gradual emancipation, followed by colonization in Africa or somewhere outside the United States. The enslaved population was large, uneducated, and without property. Many people, even those who wanted to end slavery, thought that the freed people wouldn’t be able to provide for themselves. Would whites allow them to be citizens? Could they live side by side with those who had enslaved them?

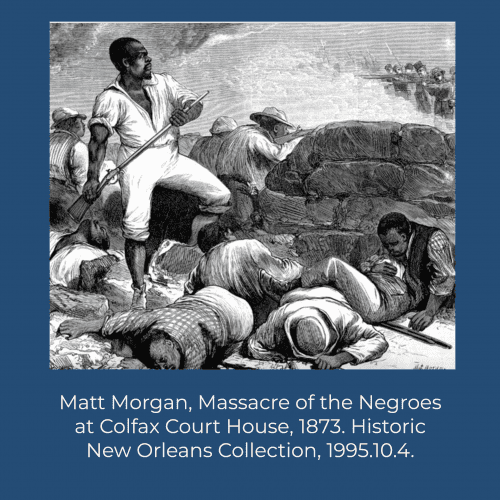

Events after emancipation showed those fears were not groundless. There was violence against African Americans and their white allies throughout Reconstruction. For example, the volume includes a document describing the 1872 Colfax Massacre in Louisiana. After Reconstruction the violence and discrimination continued.

Anyone who tries to diminish the importance of the Declaration of Independence is undermining the fight against racism. Without 1776, no other date in the history of slavery in America would matter. Each date would be just another day in the long story of humans’ inhumanity to other humans. Prior to 1776, no government had announced a commitment to human equality and justice for all. It shouldn’t surprise us that justice for all didn’t immediately become universal and hasn’t yet. But ultimately, we should defend the principles of the Declaration because they are true, and they constitute the only basis for just government.

You do not use the term “systemic racism” in discussing the persistent consequences of slavery in America. Why not?

I want to understand what happened. The term “systemic racism” disguises what happened. Systemic racism didn’t segregate the federal workforce; Woodrow Wilson did that. What in his upbringing and outlook, or in the political circumstances, led him to it? Not long before, Theodore Roosevelt had invited Booker T. Washington to dinner at the White House. Again, why did Truman desegregate the military in 1948, although FDR had been unwilling to?

If there is a constant cause, there should be a constant effect. Yet what we see throughout American history with regard to African Americans is variation. For example, Jim Crow laws were not enacted throughout the South immediately after emancipation, or as soon as Reconstruction ended. Laws segregating public transport were enacted in some places sooner, in others later, in some places not at all. You cannot explain the variation in the story by pointing to a cause as general as “systemic racism.” Not even all racists thought the same. Some wanted to allow African Americans to be a part of a more dynamic, less agrarian southern economy, for example.

Many high school teachers of American history say that their African American students dislike the subject. The textbooks used in the earlier grades show African Americans first as enslaved and later as oppressed. Then, at the end of the course, they show Martin Luther King giving a speech at the Lincoln Memorial, the laws changing, and all the problems solved. Such textbooks suggest African Americans waited until the 1960s to stand up for their rights.

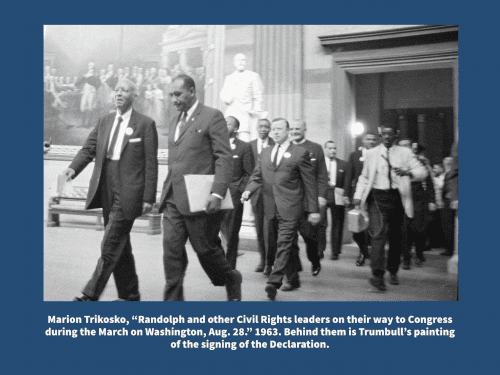

No wonder they hate history! The documents tell a different story. The second document in the collection is an anti-slavery petition written in 1777 by black residents of Massachusetts. On the cover of the collection, we have a photo of A. Philip Randolph striding into the Capitol on the day of the 1963 March on Washington. His leadership of the 1963 march is often forgotten, yet he had prepared the ground for it by threatening a March on Washington in 1942 when Roosevelt didn’t do enough to open defense industry jobs to blacks. FDR asked Randolph to call off the march. Randolph wouldn’t until FDR agreed to open up more defense jobs. How many other people made FDR back down? It’s a great story, a very American story. Success in the Civil Rights movement resulted from a long, long process of argument and activism. King was able to do what he did because so much had been done before him.

You write, “The contemporary debate over identity, race and justice, so pregnant with consequences for Americans, is itself a consequence of slavery.” Can we hope for an American future no longer marred by the consequences of slavery? How might this come about?

We should never give up that hope, because it’s the hope for a just world, perhaps the most profound and age-old human longing. But we have to temper that hope. The epigraph to the volume’s introduction quotes James Madison, who wrote that people pursue justice until they get it or lose their liberty. History suggests that the way to overcome the consequences of slavery is to enforce equality before the law for everyone. But if you make the goal the end of racism, then you are talking about rooting out evil and stupidity from the human soul. That’s something like what the abolitionists wanted. Lincoln clearly saw in them a demand for justice that would have required a tyrannical power no less destructive of liberty than slavery was. He fought both slavery and the abolitionists. Those who rage against racism today resemble the abolitionists of Lincoln’s day. They endanger freedom for the same reason.

You cannot predict when a prophet will emerge—someone with the vision and charismatic power of Fannie Lou Hamer or King, or with the eloquence and political understanding of Lincoln. I think it would take that kind of leadership to shift our current focus away from identity politics and restore a sense of our common ground as Americans. So, yes, we must hope—and read primary documents, to learn how to distinguish the true prophets from the false.