The Civil Rights Act of 1866: A First Attempt to Protect the Rights of African Americans

Today we are pleased to feature a post by Stacy Moses, a teacher at Sandia Preparatory School in Albuquerque, NM. Moses completed her Master of Arts in American History and Government degree in 2017, submitting the thesis, “Not Even Grant Could Save the Country: Reconstruction, the Resistance of the South, and the Expansion of Federal Power.”

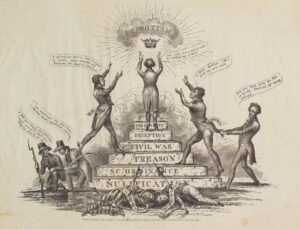

Almost immediately after the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified, and slavery was abolished nationwide, Southerners responded with the Black Codes, with organizations like the Ku Klux Klan and with the attempt to “redeem” the Southern governments—that is, to restore them to the status quo antebellum. The Civil Rights Act of 1866—enacted 155 years ago on April 9—was the first attempt of the national government to respond to and rectify the problems caused by these Redeemers. It would prove insufficient and be followed by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, designed to establish the constitutionality of federal protection of citizenship rights. These efforts competed not only with Southern designs to maintain the former racial hierarchy, but also Northern ambivalence about African American citizenship rights and the mid-19th century understanding of state vs. federal power.

Both as commander of forces under Johnson, and later, as President, Ulysses Grant was willing to use all constitutional means at his disposal to secure equal rights and support Reconstruction governments in the South. For a while, his enforcement of Reconstruction policy was successful.

Unfortunately, although maintenance of Black social and political rights might have been a priority for Lincoln and Grant, the general population of the Union—both North and South—did not, on the whole, share their goals of equality. As historian C. Vann Woodward pointed out in The Strange Career of Jim Crow, “when its victory was complete and the time came, the North was not in the best possible position to instruct the South, either by precedent and example or by force of conviction, on the implementation of what eventually became one of the professed war aims of the Union cause—racial equality.” In fact, according to Woodward, segregation as a practice germinated in the cities, especially in the North, and was fully established in the free states before moving to the South. Woodward’s account is supported by the observations of Alexis de Toqueville, who early in the 19th Century confessed surprise that racial intolerance was most prevalent in the states that had never allowed slavery. Although Radical Republicans passed laws to ensure protection of the freedmen’s rights, those staffing the Freedmen’s Bureau did not zealously enforce these laws. Nor did the Reconstruction governments—the presidentially appointed governors and their staffs, put in place immediately after the war—support their enforcement. Discriminatory practices continued throughout the South, with the Reconstruction governments’, and Johnson’s, tacit consent.

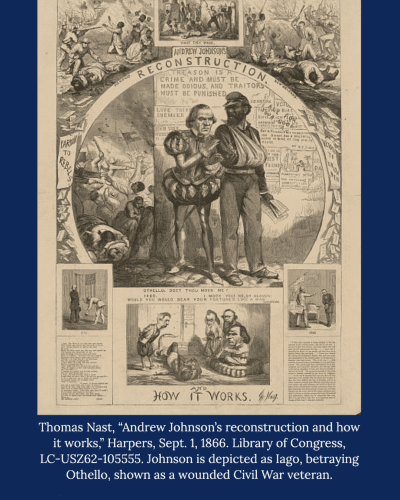

When Lincoln planned for Reconstruction, he foresaw that the central challenge involved balancing the rights of Black Southerners, Black Northerners, White Republicans who might or might not be in favor of true equality, and the myriad interests of his party members in Congress, both moderate and radical. As the War drew to a close, Lincoln became more and more concerned with upholding the rights of the Black Southerners. His last public speech signaled that he thought freedmen should eventually gain the suffrage. Without the vote, freedmen would have no way of protecting themselves. When Johnson assumed the Presidency, most Radical Republicans thought he would support this view. They were surprised by Johnson’s benevolent attitude toward the former Confederates. Tensions between the President and Congress became more and more evident. Even the moderate wing of Congress became frustrated with Johnson’s unwillingness to press for black suffrage and his easy terms for readmission of the Southern states to the Union.

When Lincoln planned for Reconstruction, he foresaw that the central challenge involved balancing the rights of Black Southerners, Black Northerners, White Republicans who might or might not be in favor of true equality, and the myriad interests of his party members in Congress, both moderate and radical. As the War drew to a close, Lincoln became more and more concerned with upholding the rights of the Black Southerners. His last public speech signaled that he thought freedmen should eventually gain the suffrage. Without the vote, freedmen would have no way of protecting themselves. When Johnson assumed the Presidency, most Radical Republicans thought he would support this view. They were surprised by Johnson’s benevolent attitude toward the former Confederates. Tensions between the President and Congress became more and more evident. Even the moderate wing of Congress became frustrated with Johnson’s unwillingness to press for black suffrage and his easy terms for readmission of the Southern states to the Union.

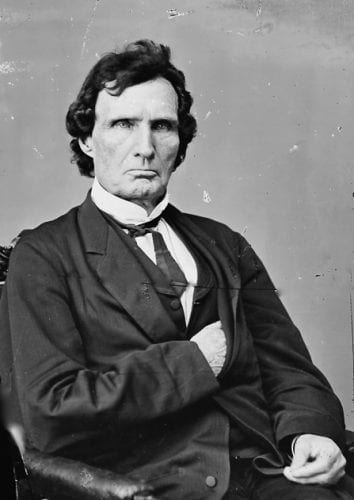

Congress, LC-DIG-cwpbh-04464 .

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 was the second of two bills proposed by Senator Lyman Trumbull of Illinois. The first bill was intended to provide the resources and power needed to support the newly-formed Freedmen’s Bureau. It extended funding for the Bureau and gave it authority to uphold black civil rights. Because the Freedmen’s Bureau was intended to be a short-lived agency, Senator Trumbull also proposed a second bill to give civil rights for the freedmen permanent recognition. That bill identified “All persons born in the United States (except Indians) as national citizens,” entitled to the protection of all rights belonging to citizens. Freedmen would now be protected by existing employment laws; contracts they signed would be legally binding; and, when accused of a crime, they would be entitled to due process, like other free-born persons. The bill was also intended to correct Chief Justice Roger Taney’s definition of citizenship in his opinion in Dred Scott; the bill said birthright citizenship belonged to (almost) all races. Additionally, the Civil Rights Bill gave Bureau officials power to enforce federal law within the states and to punish those who violated the civil rights of both black and white citizens.

According to Eric Foner, the Civil Rights Bill was the “first attempt to give meaning to the Thirteenth Amendment, to define in legislative terms the essence of freedom.” It was intended to undermine the Black Codes that several Southern states had put in place. More than that, it heralded a new and strikingly different relationship between the states and the national government, planting more power at the federal level to try cases involving denials of individual rights.

What the bill did not do was remove all power from the states. It did not provide for the political rights of blacks, and it did not go very far to secure land for the freedmen. It did, however, affect race relations in the North, almost to the same degree as it did in the South.

President Johnson denounced the bill as an encroachment of the national government into state jurisdictions. He called it federal usurpation—especially since, he said, the states themselves had provisions protecting citizens and aliens. He condemned the use of an extra-governmental force (official agents, who according to the bill, were to be appointed by commissioners appointed by the federal circuit courts), to sustain and protect the former slaves in their exercise of rights. In a move that surprised even President Johnson’s supporters, and in what Foner called the “most disastrous miscalculation of his political career” he vetoed both of the bills Trumbull had proposed. Congress overrode the vetoes of both bills, but it was a harbinger of things to come. Johnson would veto virtually every subsequent bill having to do with Reconstruction, and every veto would be overridden by Congress.

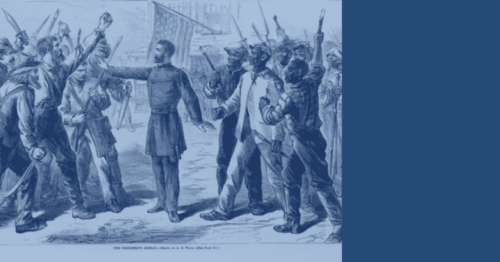

Federal intervention had some effect during the early days of Reconstruction, because of the military force under General Grant, General Phil Sheridan and General Edward Ord, especially. One Bureau agent working in the region encompassing Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas and Mississippi reported in the fall of 1867 that violence against African Americans had virtually ceased.

Still, to shore up the protection of citizenship rights, Ohio Congressman John Bingham proposed what would later become the Fourteenth Amendment. Bingham’s proposal, in the view of many, implied a great expansion of Federal power. In the key portion of its final wording, the amendment said:

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

However, in February of 1866, when Congress began to debate an amendment to protect citizenship rights, members questioned whether the amendment should protect the rights of all Americans, or only those in the formerly rebellious states that violated the rights of their citizens? Also, should the protections apply to white as well as black citizens? Others asked what the phrase “equal protection” meant, and whether Congressional legislation should override state legislation in all cases, or only in a select few? The expansion of federal power was evidently an issue with which the legislators had some discomfort, likely stemming, at least in part, from their Northern constituencies.

In May 1866, when debate on the Amendment continued, Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania called it essential to protecting the rights of citizens at the state level. Stevens, joined by M. Russell Thayer, also of Pennsylvania, and James Garfield of Ohio, argued that the Civil Rights Act was likely to be vetoed by President Johnson and could be repealed after all the Southern states were readmitted to the Union. John Bingham of Ohio argued that the Fourteenth Amendment would not remove any existing power from a state, but would instead give the national government the power to protect citizens if and when a state violated anyone’s rights. The amendment would finally make the Bill of Rights fully operative, overriding state laws that contradicted it. Jacob Howard of Michigan pointed out that if citizens’ rights weren’t being violated by the states, there would be no need for the Fourteenth Amendment. The Amendment passed in June and was ratified in July of 1868, Congress having made ratification of the 14th Amendment a requirement for the former Confederate states to regain their representation in Congress.

As Johnson completed what would have been Lincoln’s second term, white, Democrat governments of the South undermined the initial strides the Republicans made to secure citizenship for the former slaves. Meanwhile, the border states, not subject to the Reconstruction Acts, made no effort at all toward enfranchising African-Americans. Since the right of suffrage is also not guaranteed by any part of the Constitution, Congress saw the necessity of the Fifteenth Amendment, which gave suffrage to all male citizens. Again, Congress made ratification of the amendment a condition of representation in Congress for states readmitted to the Union.

Theoretically, the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments affected the legal status of African Americans in the North as well as the South, because they extended Federal authority over all citizens. However, Supreme Court decisions of the late 19th Century held that these amendments protected citizens only from denial of their rights by federal authority. As the 19th Century ended, the prospect of Civil Rights protections for Blacks became ever more elusive.