No related resources

Introduction

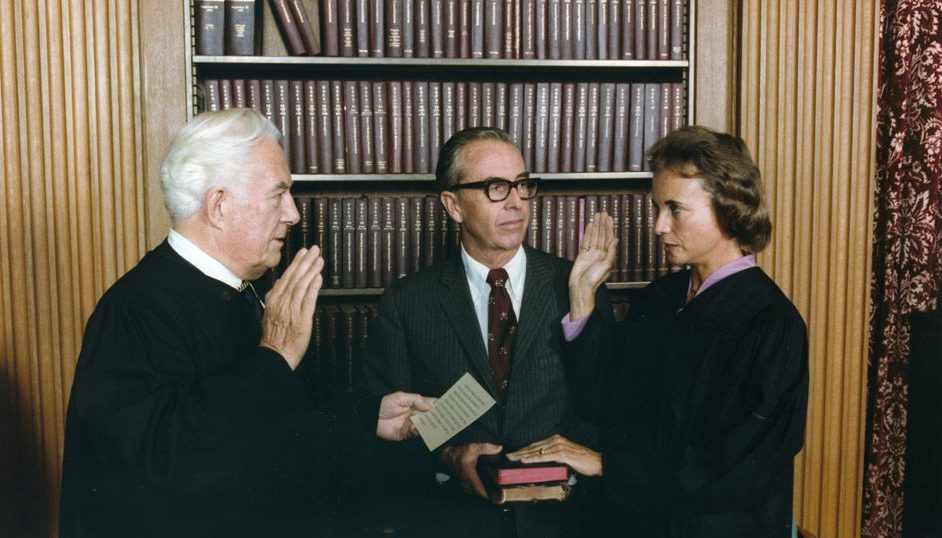

Sandra Day O’Connor (1930– ), the first female U.S. Supreme Court justice, delivered this speech on the one-hundredth anniversary of New York University’s decision to admit women to its law school. This speech illuminates how she viewed her role as the Court’s first female justice and what influence she thought being a woman should have in judicial decision making. O’Connor graduated third in her class at Stanford Law in 1952 but struggled to find a position other than legal secretary. She went on to serve as a state senator, state judge, and finally Supreme Court justice. In this lecture she outlined the struggles women faced to achieve success as lawyers and judges and then documented their statutory and constitutional successes in eliminating sex-based discrimination. But she then turned to critique the “New Feminism,” which had resurrected old stereotypes about women that had historically been used to discriminate against them. She seemed particularly disturbed by the suggestion that women would reach different legal conclusions simply because of their sex. When addressing the question “Do women judges decide cases differently by virtue of being women?” she said, “I would echo the answer of my colleague, Justice Jeanne Coyne of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma, who responded that ‘a wise old man and a wise old woman reach the same conclusion.’”

The title of Justice O’Connor’s talk comes from Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. Portia is an intelligent woman who must pretend to be a man in order to participate in a trial as a lawyer.

Source: Sandra Day O’Connor, Portia’s Progress, 66 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1546 (1991) http://www.law.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/ECM_PRO_059255.pd

I am very happy to be celebrating with you the One-Hundredth Anniversary of Women Graduates from New York University School of Law. New York University showed great foresight by admitting women law students before the turn of the century. It was one of the first major law schools to do so. Columbia Law School did not admit women until 1927; Harvard Law School did not admit women until 1950. In fact, New York University flouted the wishes of Columbia Law School committee member George Templeton Strong, who had written in his diary: “Application from three infatuated Young Women to the [Columbia] Law School. No woman shall degrade herself by practicing law in New York especially if I can save her.”

New York women wouldn’t be saved, however. The first woman to sit on the federal bench was a New Yorker, as was the first woman admitted to practice before the Supreme Court. A New York woman wrote the state’s first workmen’s compensation law, and a New York woman wrote the “Little Wagner” act that permitted New York City employees to bargain collectively without violating antitrust laws. And a New York woman worked on every major civil rights case that came before the United States Supreme Court in the 1950s and 1960s. You all can be very proud of this tradition. But being an early woman lawyer was not an easy accomplishment, even for New Yorkers.

Most of the women legal pioneers faced a profession and a society that espoused what has been called “The Cult of Domesticity,” a view that women were by nature different from men. Women were said to be fitted for motherhood and home life, compassionate, selfless, gentle, moral, and pure. Their minds were attuned to art and religion, not logic. Men, on the other hand, were fitted by nature for competition and intellectual discovery in the world, battle-hardened, shrewd, authoritative, and tough-minded.

Women were thought to be ill-qualified for adversarial litigation because it required sharp logic and shrewd negotiation, as well as exposure to the unjust and immoral. In 1875, the Wisconsin Supreme Court told Lavinia Goodell that she could not be admitted to the state bar. The Chief Justice declared that the practice of law was unfit for the female character. To expose women to the brutal, repulsive, and obscene events of courtroom life, he said, would shock man’s reverence for womanhood and relax the public’s sense of decency. . . .

In my own time and in my own life, I have witnessed the revolution in the legal profession that has resulted in women representing nearly 30 percent of attorneys in this country and 40 percent of law school graduates. Projections based on data from the Census Bureau and Department of Labor indicate that forty years hence half the country’s attorneys will be women.1 I myself, after graduating near the top of my class at Stanford Law School, was unable to obtain a position at any national law firm, except as a legal secretary. Yet I have since had the privilege of serving as a state senator, a state judge, and a Supreme Court justice.

Women today are not only well-represented in law firms, but are gradually attaining other positions of legal power, representing 7.4 percent of federal judges, 25 percent of United States attorneys, 14 percent of state attorneys, 18 percent of state legislators,17 percent of state and local executives, 9 percent of county governing boards, 14 percent of mayors and city council members, 6 percent of United States congresspersons, and of course, just over 11 percent of United States Supreme Court justices. Until the percentages come closer to 50 percent, however, we cannot say we have succeeded.

Still, the progress in my own time has been astounding.

That progress is due in large part to the explosion of the myth of the “True Woman” through the efforts of real women and the insights of real men. Released from these prejudices, women have proved they can do a “man’s” job. . . .

[In its jurisprudence], the Court has [come to look] with a somewhat jaundiced eye at the loose-fitting generalizations, myths, and archaic stereotypes that previously kept women at home. Instead, the Court has often asked employers to look to whether the particular person involved, male or female, is capable of doing the job, not whether women in general are more or less capable than men.

Just when the Court and Congress have adopted a less sanguine view of gender-based classifications, however, the new presence of women in the law has prompted many feminist commentators to ask whether women have made a difference to the profession, whether women have different styles, aptitudes, or liabilities. Ironically, the move to ask again the question whether women are different merely by virtue of being women recalls the old myths we have struggled to put behind us. Undaunted by the historical resonances, however, more and more writers have suggested that women practice law differently than men. One author has even concluded that my opinions differ in a peculiarly feminine way from those of my colleagues.

The gender differences currently cited are surprisingly similar to stereotypes from years past. Women attorneys are more likely to seek to mediate disputes than litigate them. Women attorneys are more likely to focus on resolving a client’s problem than on vindicating a position. Women attorneys are more likely to sacrifice career advancement for family obligations. Women attorneys are more concerned with public service or fostering community than with individual achievement. Women judges are more likely to emphasize context and deemphasize general principles. Women judges are more compassionate. And so forth.

This “New Feminism” is interesting, but troubling, precisely because it so nearly echoes the Victorian myth of the “True Woman” that kept women out of law for so long. It is a little chilling to compare these suggestions to Clarence Darrow’s assertion that women are too kind and warmhearted to be shining lights at the bar.

One difference between men and women lawyers certainly remains, however. Women professionals still have primary responsibility for children and housekeeping, spending roughly twice as much time on these cares as do their professional husbands. As a result, women lawyers have special difficulties managing both a household and a career.

These concerns of how to blend law and family we share with women lawyers of over one hundred years ago, who, like us, debated whether a woman could have both a family and a profession. The prevailing view then, as Mrs. Marion Todd put it in an 1888 letter to the Women Lawyers’ Equity Club, was that a husband was simply “too great a responsibility.”

Today, while many women juggle both profession and home admirably, it is nonetheless true that time spent at home is time that cannot be billed to clients or used to make contacts at social or professional organizations. As a result, women still may face what has been called a “mommy track” or a “glass ceiling” in the legal profession—a delayed or blocked ascent to partnership or management status due to family responsibilities. Women who do not wish to be left behind sometimes are faced with a hard choice. Some give up family life in order to attain their career aspirations. Many talented young women lawyers decide that the demands of a career require delaying family responsibilities at the very time in their lives when bearing children is physically easiest. I myself chose to try to have and enjoy my family and to resume my career path somewhat later.

The choices that women must make in this respect are different from the choices that men must make. Men need not take time off from work to have a family—not even the bare minimum amount of time needed to deliver a child. It is in recognizing and responding to this fundamental difference that the Court has had its most difficult challenges. The dilemma is this: if society does not recognize the fact that only women can bear children, then “equal treatment” ends up being unequal. On the other hand, if society recognizes pregnancy as requiring special solicitude, it is a slippery slope back to the “protectionist” legislation that historically barred women from the workplace. . . .

The question of when equality requires accommodating differences is one with which the Court will continue to struggle. I think in recent cases the Court has acknowledged, along with the “New Feminism,” that sometimes to treat men and women exactly the same is to treat them differently, at least with respect to pregnancy. Women do have the gift of bearing children, a gift that needs to be accommodated in the working world. However, in allowing for this difference, we must always remember that we risk a return to the myth of the “True Woman” that blocked the career paths of many generations of women.

I would hope that your generation of attorneys will find new ways to balance family and professional responsibilities between men and women, recognizing gender differences in a way that promotes equality and frees both women and men from traditional role limitations. You must reopen the velvet curtain between work and home that was drawn closed in the Victorian era. Not only women, but men too, have missed out through the division of work and home. As more women enjoy the challenges of a legal career, more men have blessings to garner from taking extra time to nurture and teach their children.

If we are to continue to find ways to repair the existing difference between professional women and men with regard to family responsibilities, however, we must not allow the “New Feminism” complete sway. For example, asking whether women attorneys speak with a “different voice” than men do is a question that is both dangerous and unanswerable. It again sets up the polarity between the feminine virtues of homemaking and the masculine virtues of breadwinning. It threatens, indeed, to establish new categories of “women’s work” to which women are confined and from which men are excluded.

Instead, my sense is that as women continue to take on a full role in the professions, learning from those professional experiences, as from their experiences as homemakers, the virtues derived from both kinds of learning will meld. The “different voices” will teach each other. I myself have been thankful for the opportunity to experience a rich and fulfilling career as well as a close and supportive family life. I know the lessons I have learned in each have aided me in the other. As a result, I can revel both in the growth of my granddaughter and in the legal subtleties of the free exercise clause.

Do women judges decide cases differently by virtue of being women? I would echo the answer of my colleague, Justice Jeanne Coyne of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma, who responded that “a wise old man and a wise old woman reach the same conclusion.” This should be our aspiration: that, whatever our gender or background, we all may become wise—wise through our different struggles and different victories, wise through work and play, profession and family.

- 1. In 2020, about 38 percent of attorneys in the United States were women.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.