No related resources

Introduction

In this case, the Court considered expanding its Establishment Clause doctrine involving school prayer (See Engel b. Vitale) and government aid to schools (see Lemon v. Kurtzman) to Christmas displays on public property. In Lynch, the Court ruled 5 to 4 that such displays do not necessarily violate the First Amendment, but the displays must observe certain conditions that make it clear the government is not endorsing any religion, presumably by including seasonal decoration, which indicate that no religious doctrine is being promulgated and the display has a secular purpose of, for example, encouraging commercial activity. The Court subsequently applied Lynch to distinguish between displays of a menorah and Christmas symbols on public grounds (County of Allegheny v. American Civil Liberties Union 492 US. 573). Any religious symbols, the Court argued, must not stigmatize nonadherents or encourage them to think they are not equal citizens. Therefore, a menorah served a secular purpose of religious toleration, while a crèche and angels were a divisive state endorsement of a religion.

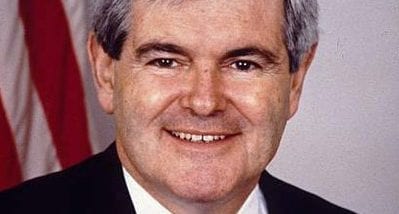

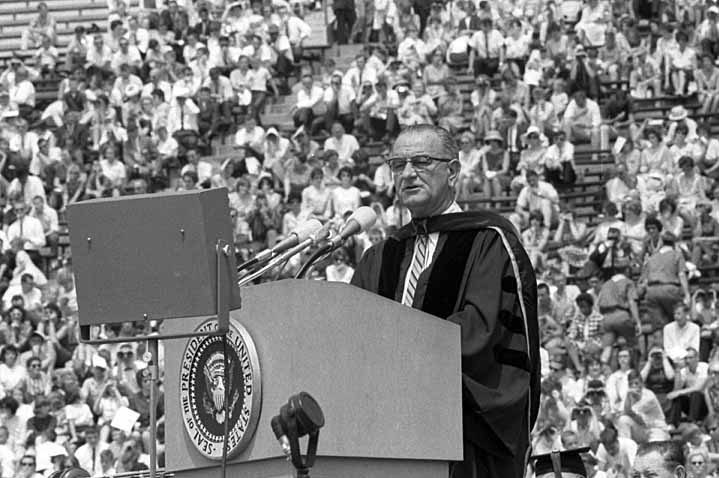

Chief Justice Warren E. Burger sets forth the facts of the case.

Source: 465 U.S. 668 (1984), https://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-supreme-court/465/668.html. We include excerpts of Chief Justice Warren E. Burger’s opinion for the Court, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s concurrence, and Justice William J. Brennan Jr.’s dissent. Footnotes added by the editors are preceded by “Ed. note.”

CHIEF JUSTICE BURGER delivered the opinion of the Court.

We granted certiorari[1] to decide whether the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment prohibits a municipality from including a crèche, or Nativity scene, in its annual Christmas display.

I

Each year, in cooperation with the downtown retail merchants’ association, the city of Pawtucket, R. I., erects a Christmas display as part of its observance of the Christmas holiday season. The display is situated in a park owned by a nonprofit organization and located in the heart of the shopping district. The display is essentially like those to be found in hundreds of towns or cities across the nation—often on public grounds—during the Christmas season. The Pawtucket display comprises many of the figures and decorations traditionally associated with Christmas, including, among other things, a Santa Claus house, reindeer pulling Santa’s sleigh, candy-striped poles, a Christmas tree, carolers, cutout figures representing such characters as a clown, an elephant, and a teddy bear, hundreds of colored lights, a large banner that reads “SEASONS GREETINGS,” and the crèche at issue here. All components of this display are owned by the city.

The crèche, which has been included in the display for 40 or more years, consists of the traditional figures, including the Infant Jesus, Mary and Joseph, angels, shepherds, kings, and animals, all ranging in height from 5 inches to 5 feet. In 1973, when the present crèche was acquired, it cost the city $1,365; it now is valued at $200. The erection and dismantling of the crèche costs the city about $20 per year; nominal expenses are incurred in lighting the crèche. No money has been expended on its maintenance for the past 10 years. . . .

II

A

This Court has explained that the purpose of the Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses of the First Amendment is “to prevent, as far as possible, the intrusion of either [the church or the state] into the precincts of the other.” Lemon v. Kurtzman , 403 U.S. 602, 614 (1971).[2] At the same time, however, the Court has recognized that “total separation is not possible in an absolute sense. Some relationship between government and religious organizations is inevitable.”[3]

In every Establishment Clause case, we must reconcile the inescapable tension between the objective of preventing unnecessary intrusion of either the church or the state upon the other, and the reality that, as the Court has so often noted, total separation of the two is not possible.

The Court has sometimes described the Religion Clauses as erecting a “wall” between church and state, see, e. g., Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S. 1, 18 . The concept of a “wall” of separation is a useful figure of speech probably deriving from views of Thomas Jefferson. The metaphor has served as a reminder that the Establishment Clause forbids an established church or anything approaching it. But the metaphor itself is not a wholly accurate description of the practical aspects of the relationship that in fact exists between church and state.

No significant segment of our society and no institution within it can exist in a vacuum or in total or absolute isolation from all the other parts, much less from government. . . . Nor does the Constitution require complete separation of church and state; it affirmatively mandates accommodation, not merely tolerance, of all religions, and forbids hostility toward any. Anything less would require the “callous indifference” we have said was never intended by the Establishment Clause. Indeed, we have observed, such hostility would bring us into “war with our national tradition as embodied in the First Amendment’s guaranty of the free exercise of religion.” McCollum, supra, at 211-212.

C

There is an unbroken history of official acknowledgment by all three branches of government of the role of religion in American life from at least 1789. Seldom in our opinions was this more affirmatively expressed than in Justice Douglas’ opinion for the Court validating a program allowing release of public school students from classes to attend off-campus religious exercises. Rejecting a claim that the program violated the Establishment Clause, the Court asserted pointedly:

“We are a religious people whose institutions presuppose a Supreme Being.” Zorach v. Clauson.

Our history is replete with official references to the value and invocation of Divine guidance in deliberations and pronouncements of the Founding Fathers and contemporary leaders. Beginning in the early colonial period long before Independence, a day of Thanksgiving was celebrated as a religious holiday to give thanks for the bounties of nature as gifts from God. . . .

III

This history may help explain why the Court consistently has declined to take a rigid, absolutist view of the Establishment Clause. We have refused “to construe the Religion Clauses with a literalness that would undermine the ultimate constitutional objective as illuminated by history.” Walz v. Tax Comm’n, 397 U.S. 664, 671 (1970). . . .

In each case, the inquiry calls for line-drawing; no fixed, per se[4] rule can be framed. The Establishment Clause like the Due Process Clauses is not a precise, detailed provision in a legal code capable of ready application. The purpose of the Establishment Clause “was to state an objective, not to write a statute.” Walz, supra, at 668. . . .

In the line-drawing process we have often found it useful to inquire whether the challenged law or conduct has a secular purpose, whether its principal or primary effect is to advance or inhibit religion, and whether it creates an excessive entanglement of government with religion.[5] But, we have repeatedly emphasized our unwillingness to be confined to any single test or criterion in this sensitive area. . . .

In this case, the focus of our inquiry must be on the crèche in the context of the Christmas season. See, e. g., Stone v. Graham, 449 U.S. 39 (1980). . . . In Stone, for example, we invalidated a state statute requiring the posting of a copy of the Ten Commandments on public classroom walls. But the Court carefully pointed out that the Commandments were posted purely as a religious admonition, not “integrated into the school curriculum, where the Bible may constitutionally be used in an appropriate study of history, civilization, ethics, comparative religion, or the like.” Similarly, in Abington, although the Court struck down the practices in two states requiring daily Bible readings in public schools, it specifically noted that nothing in the Court’s holding was intended to “indicat[e] that such study of the Bible or of religion, when presented objectively as part of a secular program of education, may not be effected with the First Amendment.” Focus exclusively on the religious component of any activity would inevitably lead to its invalidation under the Establishment Clause.

The Court has invalidated legislation or governmental action on the ground that a secular purpose was lacking, but only when it has concluded there was no question that the statute or activity was motivated wholly by religious considerations. . . .

The narrow question is whether there is a secular purpose for Pawtucket’s display of the crèche. The display is sponsored by the city to celebrate the holiday and to depict the origins of that holiday. These are legitimate secular purposes.[6] . . .

We are unable to discern a greater aid to religion deriving from inclusion of the crèche than from these benefits and endorsements previously held not violative of the Establishment Clause. What was said about the legislative prayers in Marsh and implied about the Sunday Closing Laws in McGowan is true of the city’s inclusion of the crèche: its “reason or effect merely happens to coincide or harmonize with the tenets of some . . . religions.” See McGowan, supra, at 442.

The dissent asserts some observers may perceive that the city has aligned itself with the Christian faith by including a Christian symbol in its display and that this serves to advance religion. . . . Here, whatever benefit there is to one faith or religion or to all religions, is indirect, remote, and incidental; display of the crèche is no more an advancement or endorsement of religion than the Congressional and Executive recognition of the origins of the holiday itself as “Christ’s Mass,” or the exhibition of literally hundreds of religious paintings in governmentally supported museums.

The district court found that there had been no administrative entanglement between religion and state resulting from the city’s ownership and use of the crèche. But it went on to hold that some political divisiveness was engendered by this litigation. . . .

Entanglement is a question of kind and degree. In this case, however, there is no reason to disturb the district court’s finding on the absence of administrative entanglement. . . . There is nothing here, of course, like the “comprehensive, discriminating, and continuing state surveillance” or the “enduring entanglement” present in Lemon, 403 U.S., at 619 -622.

. . . [A]part from this litigation there is no evidence of political friction or divisiveness over the crèche in the 40-year history of Pawtucket’s Christmas celebration. . . .

We are satisfied that the city has a secular purpose for including the crèche, that the city has not impermissibly advanced religion, and that including the crèche does not create excessive entanglement between religion and government.

IV

Justice Brennan describes the crèche as a “re-creation of an event that lies at the heart of Christian faith.” The crèche, like a painting, is passive; admittedly it is a reminder of the origins of Christmas. Even the traditional, purely secular displays extant at Christmas, with or without a crèche, would inevitably recall the religious nature of the Holiday. The display engenders a friendly community spirit of goodwill in keeping with the season. The crèche may well have special meaning to those whose faith includes the celebration of religious Masses, but none who sense the origins of the Christmas celebration would fail to be aware of its religious implications. That the display brings people into the central city, and serves commercial interests and benefits merchants and their employees, does not, as the dissent points out, determine the character of the display. That a prayer invoking Divine guidance in Congress is preceded and followed by debate and partisan conflict over taxes, budgets, national defense, and myriad mundane subjects, for example, has never been thought to demean or taint the sacredness of the invocation. . . .

Taken together [our] cases abundantly demonstrate the Court’s concern to protect the genuine objectives of the Establishment Clause. It is far too late in the day to impose a crabbed reading of the clause on the country. . . .

JUSTICE O’CONNOR, concurring.

I concur in the opinion of the Court. I write separately to suggest a clarification of our Establishment Clause doctrine. . . .

I

The Establishment Clause prohibits government from making adherence to a religion relevant in any way to a person’s standing in the political community. Government can run afoul of that prohibition in two principal ways. One is excessive entanglement with religious institutions, which may interfere with the independence of the institutions, give the institutions access to government or governmental powers not fully shared by nonadherents of the religion, and foster the creation of political constituencies defined along religious lines. The second and more direct infringement is government endorsement or disapproval of religion. Endorsement sends a message to nonadherents that they are outsiders, not full members of the political community, and an accompanying message to adherents that they are insiders, favored members of the political community. Disapproval sends the opposite message.

Our prior cases have used the three-part test articulated in Lemon v. Kurtzman as a guide to detecting these two forms of unconstitutional government action. It has never been entirely clear, however, how the three parts of the test relate to the principles enshrined in the Establishment Clause. Focusing on institutional entanglement and on endorsement or disapproval of religion clarifies the Lemon test as an analytical device.

II

In this case, as even the district court found, there is no institutional entanglement. Nevertheless, the respondents contend that the political divisiveness caused by Pawtucket’s display of its crèche violates the excessive-entanglement prong of the Lemon test. . . .

Although several of our cases have discussed political divisiveness under the entanglement prong of Lemon, we have never relied on divisiveness as an independent ground for holding a government practice unconstitutional. Guessing the potential for political divisiveness inherent in a government practice is simply too speculative an enterprise, in part because the existence of the litigation, as this case illustrates, itself may affect the political response to the government practice. Political divisiveness is admittedly an evil addressed by the Establishment Clause. Its existence may be evidence that institutional entanglement is excessive or that a government practice is perceived as an endorsement of religion. But the constitutional inquiry should focus ultimately on the character of the government activity that might cause such divisiveness, not on the divisiveness itself. The entanglement prong of the Lemon test is properly limited to institutional entanglement.

III

The central issue in this case is whether Pawtucket has endorsed Christianity by its display of the crèche. To answer that question, we must examine both what Pawtucket intended to communicate in displaying the crèche and what message the city’s display actually conveyed. The purpose and effect prongs of the Lemon test represent these two aspects of the meaning of the city’s action. . . .

The purpose prong of the Lemon test asks whether government’s actual purpose is to endorse or disapprove of religion. The effect prong asks whether, irrespective of government’s actual purpose, the practice under review in fact conveys a message of endorsement or disapproval. An affirmative answer to either question should render the challenged practice invalid.

A

The purpose prong of the Lemon test requires that a government activity have a secular purpose. That requirement is not satisfied, however, by the mere existence of some secular purpose, however dominated by religious purposes. . . .

Applying that formulation to this case, I would find that Pawtucket did not intend to convey any message of endorsement of Christianity or disapproval of non-Christian religions. The evident purpose of including the crèche in the larger display was not promotion of the religious content of the crèche but celebration of the public holiday through its traditional symbols. Celebration of public holidays, which have cultural significance even if they also have religious aspects, is a legitimate secular purpose. . . .

B

Focusing on the evil of government endorsement or disapproval of religion makes clear that the effect prong of the Lemon test is properly interpreted not to require invalidation of a government practice merely because it in fact causes even as a primary effect, advancement or inhibition of religion. The laws upheld in Walz v. Tax Comm’n, 397 U.S. 664 (1970) (tax exemption for religious, educational, and charitable organizations), in McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U.S. 420 (1961) (mandatory Sunday closing law), and in Zorach v. Clauson, 343 U.S. 306 (1952) (released time from school for off-campus religious instruction), had such effects, but they did not violate the Establishment Clause. What is crucial is that a government practice not have the effect of communicating a message of government endorsement or disapproval of religion. It is only practices having that effect, whether intentionally or unintentionally, that make religion relevant, in reality or public perception, to status in the political community.

Pawtucket’s display of its crèche, I believe, does not communicate a message that the government intends to endorse the Christian beliefs represented by the crèche. Although the religious and indeed sectarian significance of the crèche, as the district court found, is not neutralized by the setting, the overall holiday setting changes what viewers may fairly understand to be the purpose of the display—as a typical museum setting, though not neutralizing the religious content of a religious painting, negates any message of endorsement of that content. The display celebrates a public holiday, and no one contends that declaration of that holiday is understood to be an endorsement of religion. The holiday itself has very strong secular components and traditions. Government celebration of the holiday, which is extremely common, generally is not understood to endorse the religious content of the holiday, just as government celebration of Thanksgiving is not so understood. The crèche is a traditional symbol of the holiday that is very commonly displayed along with purely secular symbols, as it was in Pawtucket.

These features combine to make the government’s display of the crèche in this particular physical setting no more an endorsement of religion than such governmental “acknowledgements” of religion as legislative prayers of the type approved in Marsh v. Chambers 463 U.S. 783 (1983), government declaration of Thanksgiving as a public holiday, printing of “In God We Trust” on coins, and opening Court sessions with “God save the United States and this Honorable Court.” Those government acknowledgments of religion serve, in the only ways reasonably possible in our culture, the legitimate secular purposes of solemnizing public occasions, expressing confidence in the future, and encouraging the recognition of what is worthy of appreciation in society. For that reason, and because of their history and ubiquity, those practices are not understood as conveying government approval of particular religious beliefs. The display of the crèche likewise serves a secular purpose—celebration of a public holiday with traditional symbols. It cannot fairly be understood to convey a message of government endorsement of religion. It is significant in this regard that the crèche display apparently caused no political divisiveness prior to the filing of this lawsuit, although Pawtucket had incorporated the crèche in its annual Christmas display for some years. For these reasons, I conclude that Pawtucket’s display of the crèche does not have the effect of communicating endorsement of Christianity. . . .

JUSTICE BRENNAN, with whom JUSTICE MARSHALL, JUSTICE BLACKMUN, and JUSTICE STEVENS join, dissenting.

The principles announced in the compact phrases of the Religion Clauses have, as the Court today reminds us proved difficult to apply. Faced with that uncertainty, the Court properly looks for guidance to the settled test announced in Lemon v. Kurtzman, for assessing whether a challenged governmental practice involves an impermissible step toward the establishment of religion. Applying that test to this case, the Court reaches an essentially narrow result which turns largely upon the particular holiday context in which the city of Pawtucket’s nativity scene appeared. The Court’s decision implicitly leaves open questions concerning the constitutionality of the public display on public property of a crèche standing alone, or the public display of other distinctively religious symbols such as a cross. Despite the narrow contours of the Court’s opinion, our precedents in my view compel the holding that Pawtucket’s inclusion of a life-sized display depicting the biblical description of the birth of Christ as part of its annual Christmas celebration is unconstitutional. Nothing in the history of such practices or the setting in which the city’s crèche is presented obscures or diminishes the plain fact that Pawtucket’s action amounts to an impermissible governmental endorsement of a particular faith.

I

Last term, I expressed the hope that the Court’s decision in Marsh v. Chambers would prove to be only a single, aberrant departure from our settled method of analyzing Establishment Clause cases. That the Court today returns to the settled analysis of our prior cases gratifies that hope. At the same time, the Court’s less-than-vigorous application of the Lemon test suggests that its commitment to those standards may only be superficial. After reviewing the Court’s opinion, I am convinced that this case appears hard not because the principles of decision are obscure, but because the Christmas holiday seems so familiar and agreeable. Although the Court’s reluctance to disturb a community’s chosen method of celebrating such an agreeable holiday is understandable, that cannot justify the Court’s departure from controlling precedent. In my view, Pawtucket’s maintenance and display at public expense of a symbol as distinctively sectarian as a crèche simply cannot be squared with our prior cases. And it is plainly contrary to the purposes and values of the Establishment Clause to pretend, as the Court does, that the otherwise secular setting of Pawtucket’s nativity scene dilutes in some fashion the crèche’s singular religiosity, or that the city’s annual display reflects nothing more than an “acknowledgment” of our shared national heritage. Neither the character of the Christmas holiday itself, nor our heritage of religious expression supports this result. Indeed, our remarkable and precious religious diversity as a nation, which the Establishment Clause seeks to protect, runs directly counter to today’s decision. . . .

A

. . .

Applying the three-part [Lemon] test to Pawtucket’s crèche, I am persuaded that the city’s inclusion of the crèche in its Christmas display simply does not reflect a “clearly secular . . . purpose.” Nyquist, supra, at 773. Unlike the typical case in which the record reveals some contemporaneous expression of a clear purpose to advance religion or, conversely, a clear secular purpose, here we have no explicit statement of purpose by Pawtucket’s municipal government accompanying its decision to purchase, display, and maintain the crèche. Governmental purpose may nevertheless be inferred. . . . In the present case, the city claims that its purposes were exclusively secular. Pawtucket sought, according to this view, only to participate in the celebration of a national holiday and to attract people to the downtown area in order to promote pre-Christmas retail sales and to help engender the spirit of goodwill and neighborliness commonly associated with the Christmas season.

Despite these assertions, two compelling aspects of this case indicate that our generally prudent “reluctance to attribute unconstitutional motives” to a governmental body, Mueller v. Allen, 463 U.S. 388, 394 (1983), should be overcome. First, as was true in Larkin v. Grendel’s Den, Inc., 459 U.S. 116, 123-124 (1982), all of Pawtucket’s “valid secular objectives can be readily accomplished by other means.” Plainly, the city’s interest in celebrating the holiday and in promoting both retail sales and goodwill are fully served by the elaborate display of Santa Claus, reindeer, and wishing wells that are already a part of Pawtucket’s annual Christmas display. More importantly, the nativity scene, unlike every other element of the Hodgson Park display, reflects a sectarian exclusivity that the avowed purposes of celebrating the holiday season and promoting retail commerce simply do not encompass. To be found constitutional, Pawtucket’s seasonal celebration must at least be nondenominational and not serve to promote religion. The inclusion of a distinctively religious element like the crèche, however, demonstrates that a narrower sectarian purpose lay behind the decision to include a nativity scene. . . . Plainly, the city and its leaders understood that the inclusion of the crèche in its display would serve the wholly religious purpose of “keep[ing] ‘Christ in Christmas.’” 525 F. Supp. 1150, 1173 (RI 1981). From this record, therefore, it is impossible to say . . . that a wholly secular goal predominates.

The “primary effect” of including a nativity scene in the city’s display is, as the District Court found, to place the government’s imprimatur of approval on the particular religious beliefs exemplified by the crèche. Those who believe in the message of the nativity receive the unique and exclusive benefit of public recognition and approval of their views. For many, the city’s decision to include the crèche as part of its extensive and costly efforts to celebrate Christmas can only mean that the prestige of the government has been conferred on the beliefs associated with the crèche, thereby providing “a significant symbolic benefit to religion. . . .” Larkin v. Grendel’s Den, Inc., supra, at 125-126. The effect on minority religious groups, as well as on those who may reject all religion, is to convey the message that their views are not similarly worthy of public recognition nor entitled to public support. It was precisely this sort of religious chauvinism that the Establishment Clause was intended forever to prohibit. . . . Our decision in Widmar v. Vincent[7] rests upon the same principle. There the Court noted that a state university policy of “equal access” for both secular and religious groups would “not confer any imprimatur of state approval” on the religious groups permitted to use the facilities because “a broad spectrum of groups” would be served and there was no evidence that religious groups would dominate the forum. Here, by contrast, Pawtucket itself owns the crèche and instead of extending similar attention to a “broad spectrum” of religious and secular groups, it has singled out Christianity for special treatment.

Finally, it is evident that Pawtucket’s inclusion of a crèche as part of its annual Christmas display does pose a significant threat of fostering “excessive entanglement.” As the Court notes, the district court found no administrative entanglement in this case, primarily because the city had been able to administer the annual display without extensive consultation with religious officials. Of course, there is no reason to disturb that finding, but it is worth noting that after today’s decision, administrative entanglements may well develop. Jews and other non-Christian groups, prompted perhaps by the mayor’s remark that he will include a Menorah in future displays, can be expected to press government for inclusion of their symbols, and faced with such requests, government will have to become involved in accommodating the various demands. More importantly, although no political divisiveness was apparent in Pawtucket prior to the filing of respondents’ lawsuit, that act, as the district court found, unleashed powerful emotional reactions which divided the city along religious lines. The fact that calm had prevailed prior to this suit does not immediately suggest the absence of any division on the point for, as the district court observed, the quiescence of those opposed to the crèche may have reflected nothing more than their sense of futility in opposing the majority. Of course, the Court is correct to note that we have never held that the potential for divisiveness alone is sufficient to invalidate a challenged governmental practice; we have, nevertheless, repeatedly emphasized that “too close a proximity” between religious and civil authorities, Schempp, 374 U.S., at 259 (Brennan, J., concurring), may represent a “warning signal” that the values embodied in the Establishment Clause are at risk. Furthermore, the Court should not blind itself to the fact that because communities differ in religious composition, the controversy over whether local governments may adopt religious symbols will continue to fester. In many communities, non-Christian groups can be expected to combat practices similar to Pawtucket’s; this will be so especially in areas where there are substantial non-Christian minorities.

In sum, considering the District Court’s careful findings of fact under the three-part analysis called for by our prior cases, I have no difficulty concluding that Pawtucket’s display of the crèche is unconstitutional.

B

The Court advances two principal arguments to support its conclusion that the Pawtucket crèche satisfies the Lemon test. Neither is persuasive.

First. The Court, by focusing on the holiday “context” in which the nativity scene appeared, seeks to explain away the clear religious import of the crèche and the findings of the district court that most observers understood the crèche as both a symbol of Christian beliefs and a symbol of the city’s support for those beliefs. Thus, although the Court concedes that the city’s inclusion of the nativity scene plainly serves “to depict the origins” of Christmas as a “significant historical religious event,” and that the crèche “is identified with one religious faith,” we are nevertheless expected to believe that Pawtucket’s use of the crèche does not signal the city’s support for the sectarian symbolism that the nativity scene evokes. The effect of the crèche, of course, must be gauged not only by its inherent religious significance but also by the overall setting in which it appears. But it blinks reality to claim, as the Court does, that by including such a distinctively religious object as the crèche in its Christmas display, Pawtucket has done no more than make use of a “traditional” symbol of the holiday, and has thereby purged the crèche of its religious content and conferred only an “incidental and indirect” benefit on religion.

The Court’s struggle to ignore the clear religious effect of the crèche seems to me misguided for several reasons. In the first place, the city has positioned the crèche in a central and highly visible location within the Hodgson Park display. . . .

Moreover, the city has done nothing to disclaim government approval of the religious significance of the crèche, to suggest that the crèche represents only one religious symbol among many others that might be included in a seasonal display truly aimed at providing a wide catalog of ethnic and religious celebrations, or to disassociate itself from the religious content of the crèche. . . .

Third, we have consistently acknowledged that an otherwise secular setting alone does not suffice to justify a governmental practice that has the effect of aiding religion. . . .

Finally, and most importantly, even in the context of Pawtucket’s seasonal celebration, the crèche retains a specifically Christian religious meaning. . . . To be so excluded on religious grounds by one’s elected government is an insult and an injury that, until today, could not be countenanced by the Establishment Clause.

Second. The Court also attempts to justify the crèche by entertaining a beguilingly simple, yet faulty syllogism. The Court begins by noting that government may recognize Christmas Day as a public holiday; the Court then asserts that the crèche is nothing more than a traditional element of Christmas celebrations; and it concludes that the inclusion of a crèche as part of a government’s annual Christmas celebration is constitutionally permissible. . . . To say that government may recognize the holiday’s traditional, secular elements of gift-giving, public festivities, and community spirit, does not mean that government may indiscriminately embrace the distinctively sectarian aspects of the holiday. . . . As is demonstrated below, the Court’s logic is fundamentally flawed both because it obscures the reason why public designation of Christmas Day as a holiday is constitutionally acceptable, and blurs the distinction between the secular aspects of Christmas and its distinctively religious character, as exemplified by the crèche.

When government decides to recognize Christmas Day as a public holiday, it does no more than accommodate the calendar of public activities to the plain fact that many Americans will expect on that day to spend time visiting with their families, attending religious services, and perhaps enjoying some respite from preholiday activities. The Free Exercise Clause, of course, does not necessarily compel the government to provide this accommodation, but neither is the Establishment Clause offended by such a step. Because it is clear that the celebration of Christmas has both secular and sectarian elements, it may well be that by taking note of the holiday, the government is simply seeking to serve the same kinds of wholly secular goals—for instance, promoting goodwill and a common day of rest—that were found to justify Sunday Closing Laws. If public officials go further and participate in the secular celebration of Christmas—by, for example, decorating public places with such secular images as wreaths, garlands, or Santa Claus figures—they move closer to the limits of their constitutional power but nevertheless remain within the boundaries set by the Establishment Clause. But when those officials participate in or appear to endorse the distinctively religious elements of this otherwise secular event, they encroach upon First Amendment freedoms. For it is at that point that the government brings to the forefront the theological content of the holiday, and places the prestige, power, and financial support of a civil authority in the service of a particular faith.

The inclusion of a crèche in Pawtucket’s otherwise secular celebration of Christmas clearly violates these principles. . . .

II

Although the Court’s relaxed application of the Lemon test to Pawtucket’s crèche is regrettable, it is at least understandable and properly limited to the particular facts of this case. The Court’s opinion, however, also sounds a broader and more troubling theme. Invoking the celebration of Thanksgiving as a public holiday, the legend “In God We Trust” on our coins, and the proclamation “God save the United States and this Honorable Court” at the opening of judicial sessions, the Court asserts, without explanation, that Pawtucket’s inclusion of a crèche in its annual Christmas display poses no more of a threat to Establishment Clause values than these other official “acknowledgments” of religion.

Intuition tells us that some official “acknowledgment” is inevitable in a religious society if government is not to adopt a stilted indifference to the religious life of the people. It is equally true, however, that if government is to remain scrupulously neutral in matters of religious conscience, as our Constitution requires, then it must avoid those overly broad acknowledgements of religious practices that may imply governmental favoritism toward one set of religious beliefs. This does not mean, of course, that public officials may not take account, when necessary, of the separate existence and significance of the religious institutions and practices in the society they govern. Should government choose to incorporate some arguably religious element into its public ceremonies, that acknowledgment must be impartial; it must not tend to promote one faith or handicap another; and it should not sponsor religion generally over nonreligion. . . .

Despite this body of case law, the Court has never comprehensively addressed the extent to which government may acknowledge religion by, for example, incorporating religious references into public ceremonies and proclamations, and I do not presume to offer a comprehensive approach. Nevertheless, it appears from our prior decisions that at least three principles—tracing the narrow channels which government acknowledgments must follow to satisfy the Establishment Clause—may be identified. First, although the government may not be compelled to do so by the Free Exercise Clause, it may, consistently with the Establishment Clause, act to accommodate to some extent the opportunities of individuals to practice their religion. . . . And for me that principle would justify government’s decision to declare December 25 a public holiday.

Second, our cases recognize that while a particular governmental practice may have derived from religious motivations and retain certain religious connotations, it is nonetheless permissible for the government to pursue the practice when it is continued today solely for secular reasons. . . . [T]he mere fact that a governmental practice coincides to some extent with certain religious beliefs does not render it unconstitutional. Thanksgiving Day, in my view, fits easily within this principle, for despite its religious antecedents, the current practice of celebrating Thanksgiving is unquestionably secular and patriotic. We all may gather with our families on that day to give thanks both for personal and national good fortune, but we are free, given the secular character of the holiday, to address that gratitude either to a divine beneficence or to such mundane sources as good luck or the country’s abundant natural wealth.

Finally, we have noted that government cannot be completely prohibited from recognizing in its public actions the religious beliefs and practices of the American people as an aspect of our national history and culture. While I remain uncertain about these questions, I would suggest that such practices as the designation of “In God We Trust” as our national motto, or the references to God contained in the Pledge of Allegiance to the flag can best be understood, in Dean Rostow’s apt phrase, as a form a “ceremonial deism,” protected from Establishment Clause scrutiny chiefly because they have lost through rote repetition any significant religious content. Moreover, these references are uniquely suited to serve such wholly secular purposes as solemnizing public occasions, or inspiring commitment to meet some national challenge in a manner that simply could not be fully served in our culture if government were limited to purely nonreligious phrases. The practices by which the government has long acknowledged religion are therefore probably necessary to serve certain secular functions, and that necessity, coupled with their long history, gives those practices an essentially secular meaning.

The crèche fits none of these categories. Inclusion of the crèche is not necessary to accommodate individual religious expression. This is plainly not a case in which individual residents of Pawtucket have claimed the right to place a crèche as part of a wholly private display on public land. Nor is the inclusion of the crèche necessary to serve wholly secular goals; it is clear that the city’s secular purposes of celebrating the Christmas holiday and promoting retail commerce can be fully served without the crèche. And the crèche, because of its unique association with Christianity, is clearly more sectarian than those references to God that we accept in ceremonial phrases or in other contexts that assure neutrality. The religious works on display at the National Gallery, presidential references to God during an Inaugural Address, or the national motto present no risk of establishing religion. To be sure, our understanding of these expressions may begin in contemplation of some religious element, but it does not end there. Their message is dominantly secular. In contrast, the message of the crèche begins and ends with reverence for a particular image of the divine.

By insisting that such a distinctively sectarian message is merely an unobjectionable part of our “religious heritage,” the Court takes a long step backwards to the days when Justice [David J.] Brewer could arrogantly declare for the Court that “this is a Christian nation.” Church of Holy Trinity v. United States (1892). Those days, I had thought, were forever put behind us by the Court’s decision in Engel v. Vitale,[8] in which we rejected a similar argument advanced by the state of New York that its regent’s prayer was simply an acceptable part of our “spiritual heritage.”

III

The American historical experience concerning the public celebration of Christmas, if carefully examined, provides no support for the Court’s decision. . . .

Indeed, the Court’s approach suggests a fundamental misapprehension of the proper uses of history in constitutional interpretation. Certainly, our decisions reflect the fact that an awareness of historical practice often can provide a useful guide in interpreting the abstract language of the Establishment Clause. But historical acceptance of a particular practice alone is never sufficient to justify a challenged governmental action, since, as the Court has rightly observed, “no one acquires a vested or protected right in violation of the Constitution by long use, even when that span of time covers our entire national existence and indeed predates it.” Walz, supra, at 678. Attention to the details of history should not blind us to the cardinal purposes of the Establishment Clause, nor limit our central inquiry in these cases—whether the challenged practices “threaten those consequences which the Framers deeply feared.” Abington School Dist. v. Schempp, 374 U.S., at 236 (Brennan, J., concurring). In recognition of this fact, the Court has, until today, consistently limited its historical inquiry to the particular practice under review. . . .

. . . [T]he Court wholly fails to discuss the history of the public celebration of Christmas or the use of publicly displayed nativity scenes. The Court, instead, simply asserts, without any historical analysis or support whatsoever, that the now familiar celebration of Christmas springs from an unbroken history of acknowledgment “by the people, by the Executive Branch, by the Congress, and the courts for 2 centuries . . . .” The Court’s complete failure to offer any explanation of its assertion is perhaps understandable, however, because the historical record points in precisely the opposite direction. Two features of this history are worth noting. First, at the time of the adoption of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, there was no settled pattern of celebrating Christmas, either as a purely religious holiday or as a public event. Second, the historical evidence, such as it is, offers no uniform pattern of widespread acceptance of the holiday and indeed suggests that the development of Christmas as a public holiday is a comparatively recent phenomenon.

The intent of the Framers with respect to the public display of nativity scenes is virtually impossible to discern primarily because the widespread celebration of Christmas did not emerge in its present form until well into the 19th century. Carrying a well-defined Puritan hostility to the celebration of Christ’s birth with them to the New World, the founders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony pursued a vigilant policy of opposition to any public celebration of the holiday. To the Puritans, the celebration of Christmas represented a “Popish” practice lacking any foundation in scripture. . . .

Furthermore, unlike the religious tax exemptions upheld in Walz, the public display of nativity scenes as part of governmental celebrations of Christmas does not come to us supported by an unbroken history of widespread acceptance. It was not until 1836 that a state first granted legal recognition to Christmas as a public holiday. This was followed in the period between 1845 and 1865, by 28 jurisdictions which included Christmas Day as a legal holiday. Congress did not follow the states’ lead until 1870 when it established December 25, along with the Fourth of July, New Year’s Day, and Thanksgiving, as a legal holiday in the District of Columbia. This pattern of legal recognition tells us only that public acceptance of the holiday was gradual and that the practice—in stark contrast to the record presented in either Walz or Marsh—did not take on the character of a widely recognized holiday until the middle of the 19th century. . . .

In sum, there is no evidence whatsoever that the Framers would have expressly approved a federal celebration of the Christmas holiday including public displays of a nativity scene; accordingly, the Court’s repeated invocation of the decision in Marsh[9] is not only baffling, it is utterly irrelevant. Nor is there any suggestion that publicly financed and supported displays of Christmas crèches are supported by a record of widespread, undeviating acceptance that extends throughout our history. Therefore, our prior decisions which relied upon concrete, specific historical evidence to support a particular practice simply have no bearing on the question presented in this case. Contrary to today’s careless decision, those prior cases have all recognized that the “illumination” provided by history must always be focused on the particular practice at issue in a given case. Without that guiding principle and the intellectual discipline it imposes, the Court is at sea, free to select random elements of America’s varied history solely to suit the views of five members of this Court.

IV

Under our constitutional scheme, the role of safeguarding our “religious heritage” and of promoting religious beliefs is reserved as the exclusive prerogative of our nation’s churches, religious institutions, and spiritual leaders. Because the Framers of the Establishment Clause understood that “religion is too personal, too sacred, too holy to permit its `unhallowed perversion’ by civil [authorities],” Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S., at 432 , the clause demands that government play no role in this effort. . . .

- 1. Ed. note: A Latin word meaning “to be informed” or “we wish to be informed,” certiorari is an order of a higher court to review a lower court decision. “Certiorari” was the first word of such orders when they were written in Latin.

- 2. Ed. note: Widmar v. Vincent

- 3. Ed. note: Widmar v. Vincent

- 4. Ed. note: intrinsic

- 5. Ed. note: This is the so-called Lemon test. See Widmar v. Vincent.

- 6. The city contends that the purposes of the display are “exclusively secular.” We hold only that Pawtucket has a secular purpose for its display, which is all that Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602 (1971), requires. Were the test that the government must have “exclusively secular” objectives, much of the conduct and legislation this Court has approved in the past would have been invalidated.

- 7. Ed. note: Wallace v. Jeffree

- 8. Ed. note: Lemon v. Kurtzman

- 9. Ed. note: In Marsh v. Chambers, 463 U.S. 783 (1983), https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/463/783, the Court held 6 to 3 that publicly funded chaplains were constitutional because of the unique historical background of the practice.

Wallace v. Jaffree

June 04, 1985

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.