Introduction

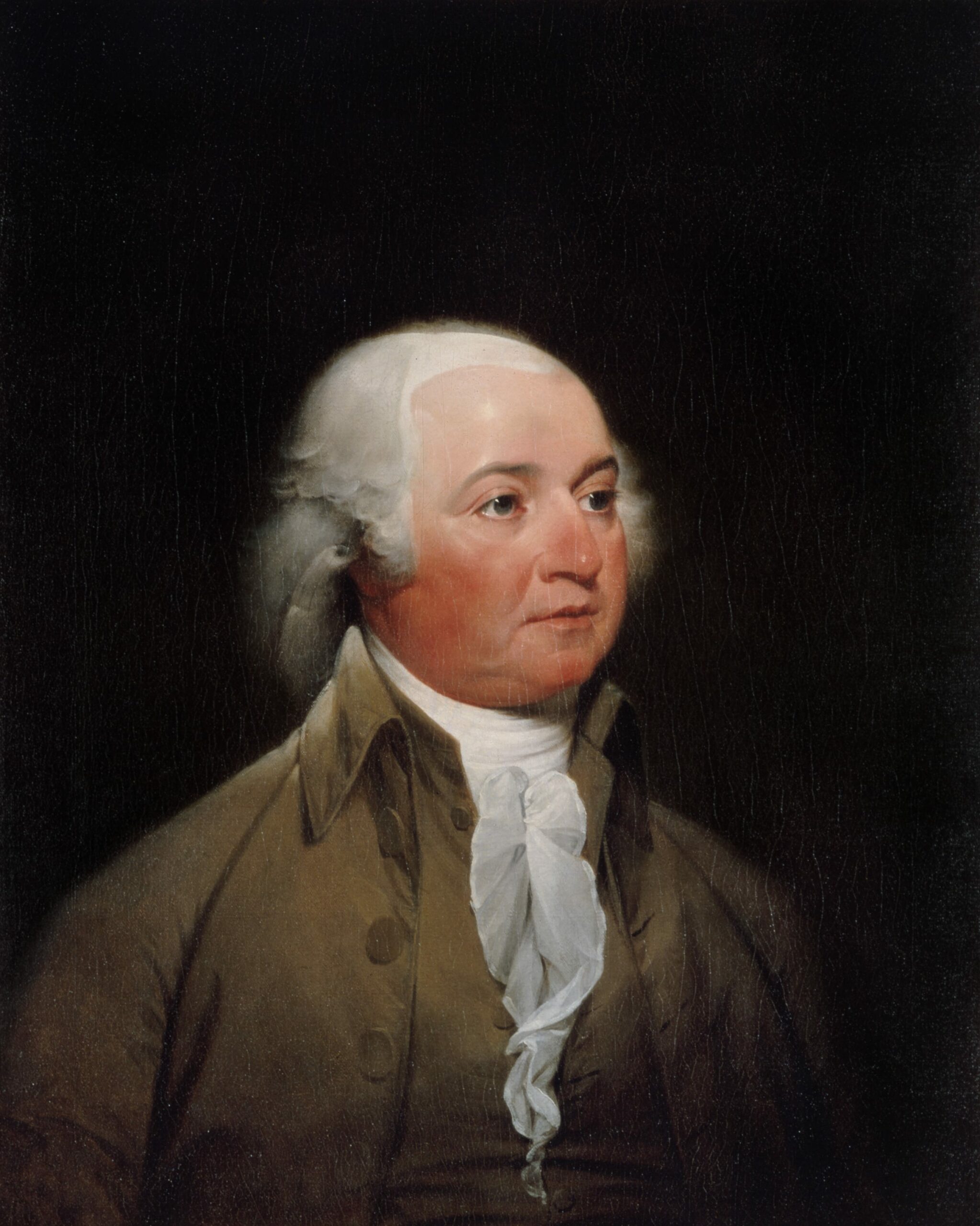

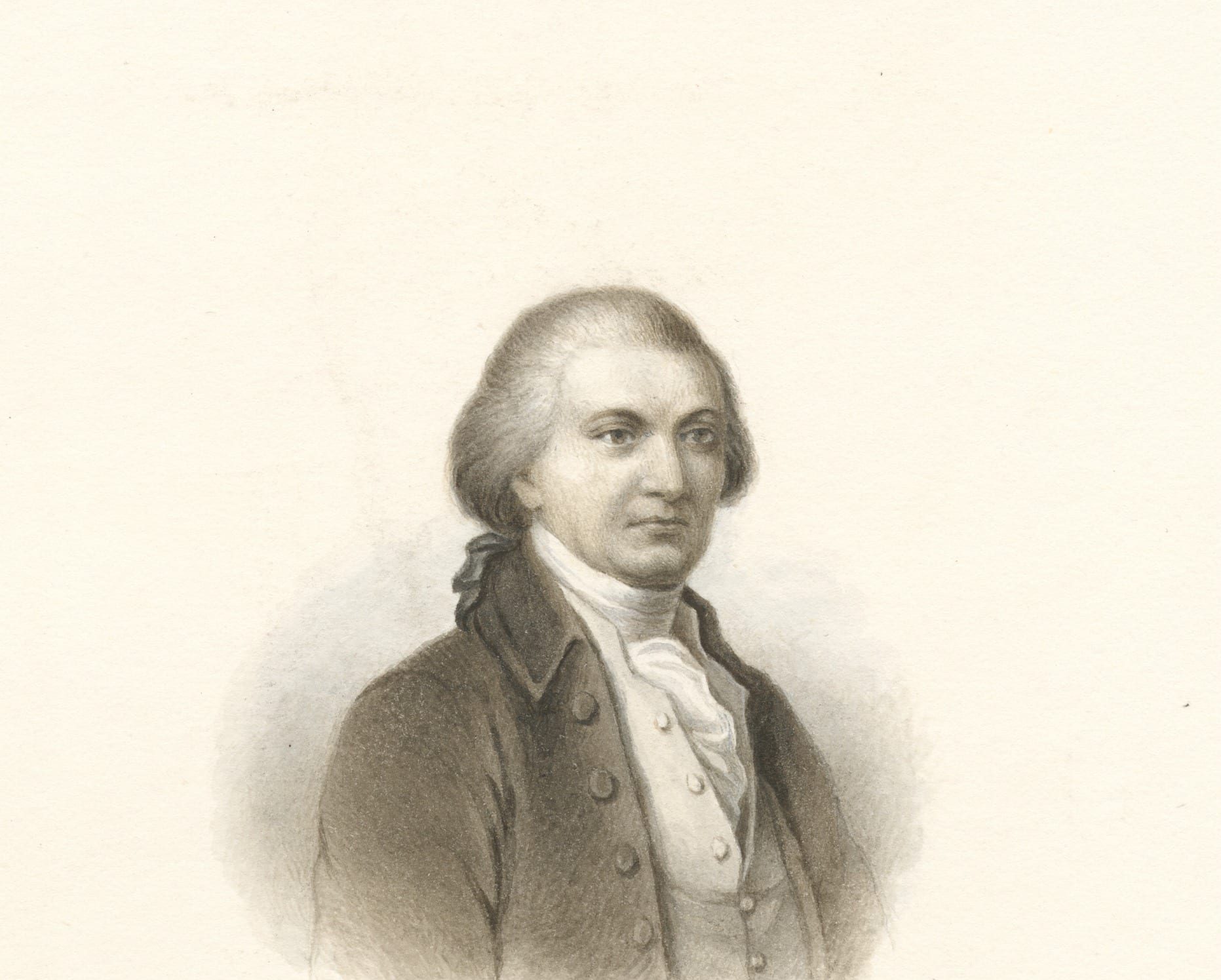

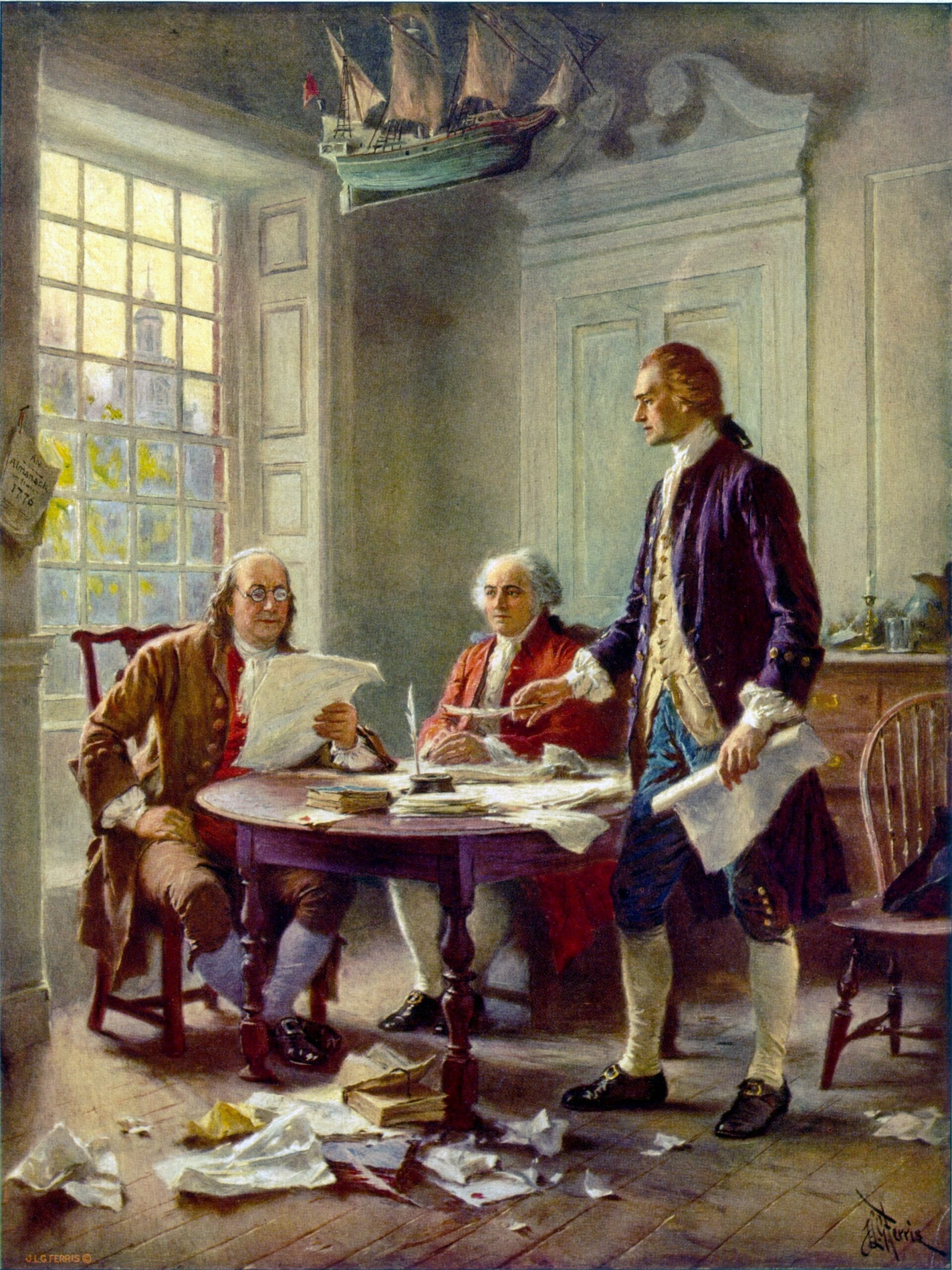

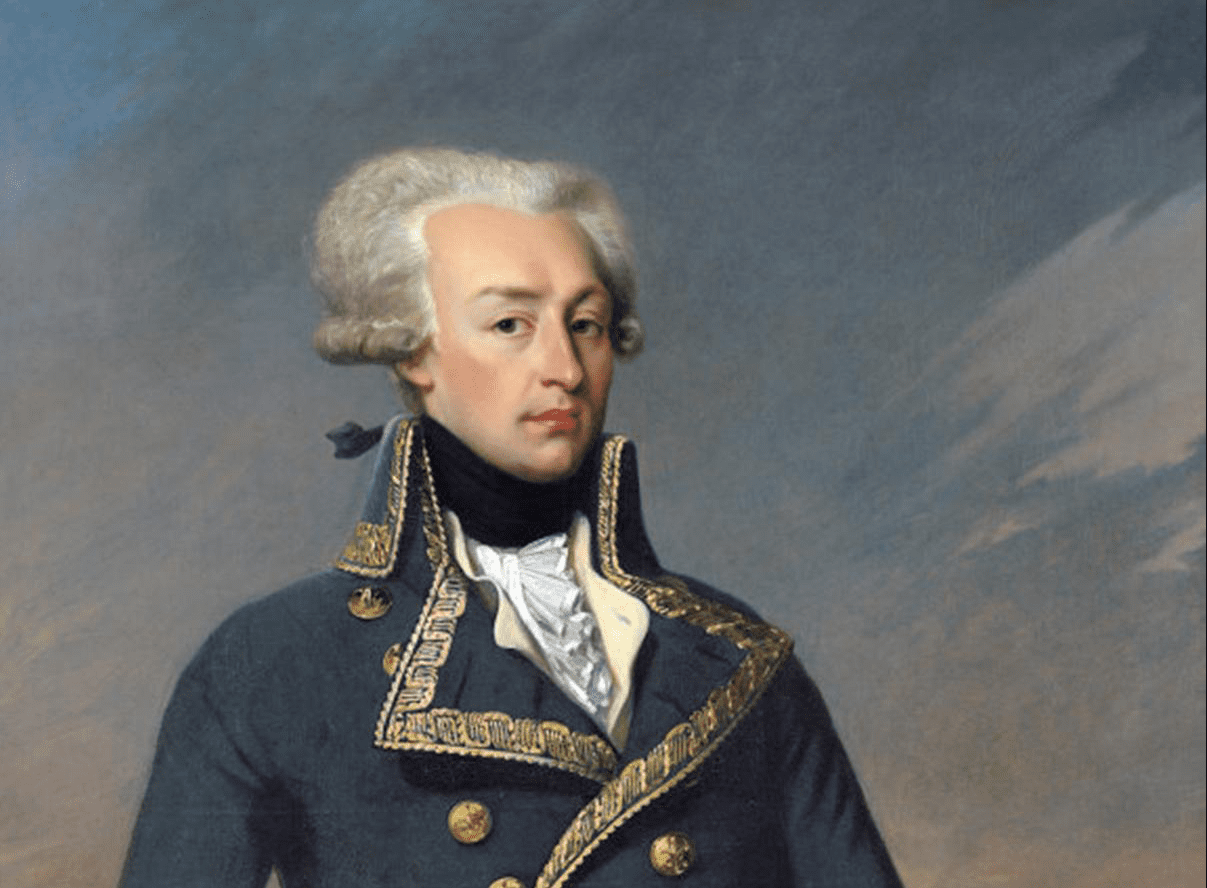

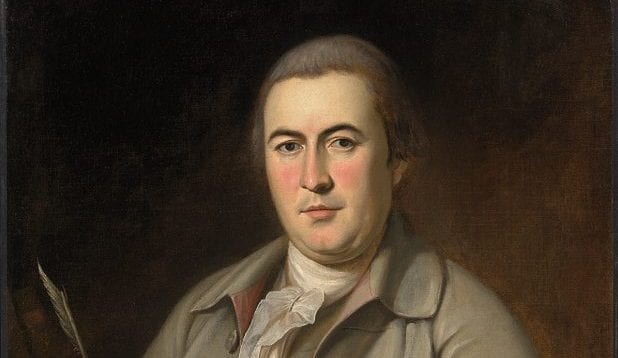

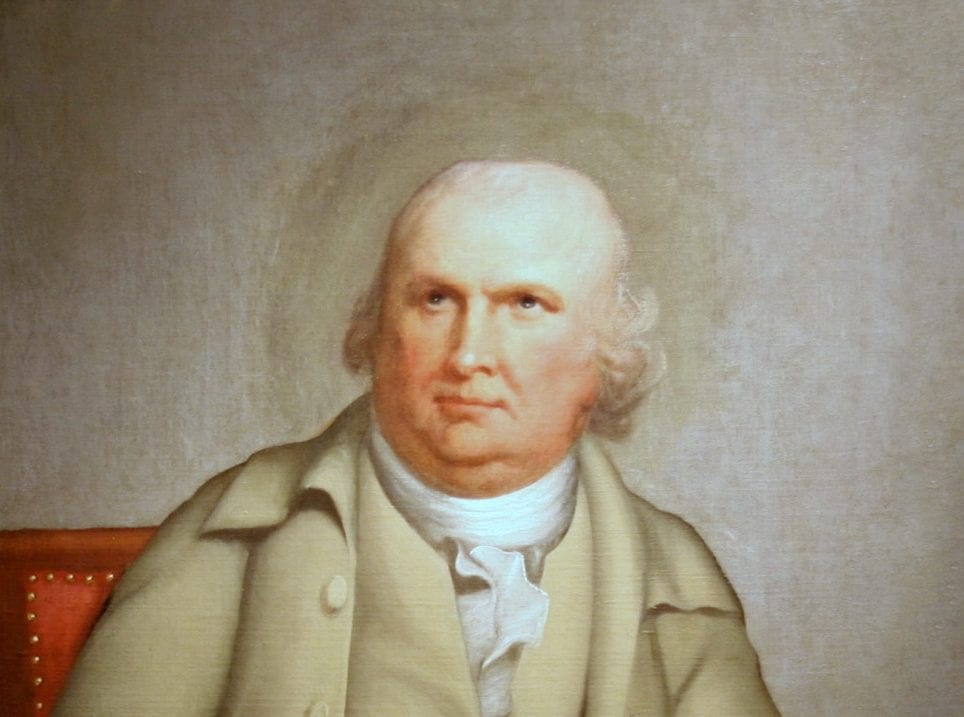

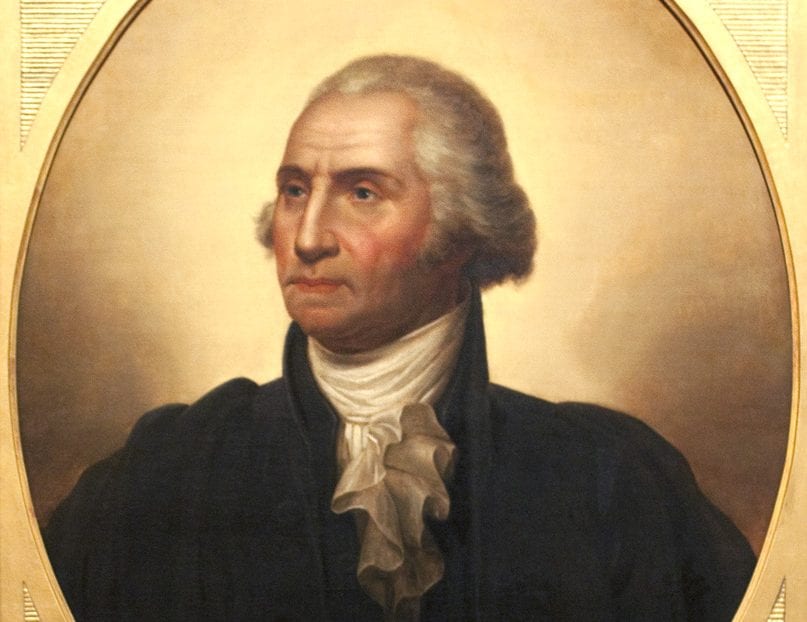

James Duane (1733–1797) was a delegate to the First Continental Congress, a signer of the Articles of Confederation, and a member of the Congress of the Confederation from 1781 until 1783. That year he sent some material related to Indian affairs to his friend George Washington, asking for his thoughts.

In his reply to Duane, the future president outlined his plan for peaceful relations with the Indians. He counseled against New York’s plan to remove the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) from their territory. Instead he advised the new nation to draw a clear boundary between whites and Indians similar to the line established in the Royal Proclamation of 1763. Rather than giving in to settlers and land speculators, he proposed that the general government police the boundary, permitting to cross it only traders licensed by the government. When it became necessary, he proposed that land be purchased fairly from the Indians rather than taking it by force of arms.

When he became president, Washington put these suggested policies into effect through measures such as the Trade and Intercourse Act of 1790. He negotiated treaties with powerful tribes like the Haudenosaunee and the Cherokee to establish the boundaries of the United States. He favored a policy of civilizing Indians, teaching them to be farmers in situ rather than removing them.

“From George Washington to James Duane, 7 September 1783,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-11798.

Sir

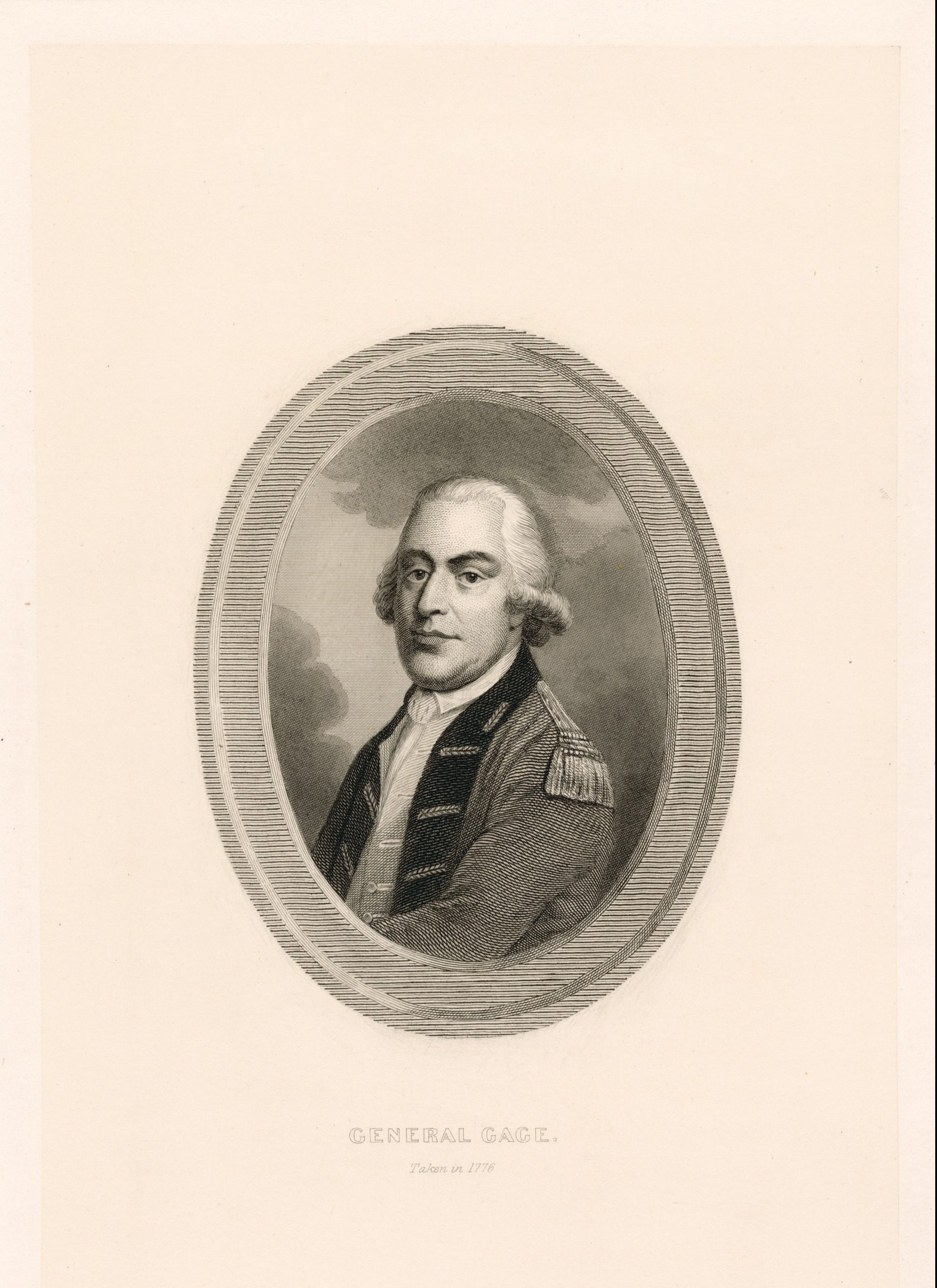

I have carefully perused the papers which you put into my hands relating to Indian affairs. My sentiments with respect to the proper line of conduct to be observed toward these people coincides precisely with those delivered by General Schuyler1 so far as he has gone in his letter of the 29th July to Congress (which, with the other papers is herewith returned)—and for the reasons he has there assigned; a repetition of them therefore by me would be unnecessary. But independent of the arguments made use of by him the following considerations have no small weight in my mind.

To suffer a wide extended country to be overrun with land jobbers—speculators and monopolizers or even with scattered settlers is, in my opinion, inconsistent with that wisdom and policy which our true interest dictates, or that an enlightened people ought to adopt; and besides, is pregnant of disputes, both with the savages and among ourselves, the evils of which are easier to be conceived than described; and for what? but to aggrandize a few avaricious men to the prejudice of many and the embarrassment of government. For the people engaged in these pursuits without contributing in the smallest degree to the support of government, or considering themselves as amenable to its laws, will involve it by their unrestrained conduct in inextricable perplexities, and more than probable in a great deal of bloodshed.

My ideas therefore of the line of conduct proper to be observed not only toward the Indians, but for the government of the citizens of America in their settlement of the western country (which is intimately connected therewith) are simply these.

First and as a preliminary, that all prisoners of whatever age or sex, among the Indians shall be delivered up.

That the Indians should be informed that after a contest of eight years for sovereignty of the country Great Britain has ceded all the lands of the United States within the limits described by the———part of the Provisional Treaty.2

That as they (the Indians) maugre3 all the advice and admonition which could be given them at the commencement, and during the prosecution of the war could not be restrained from acts of hostility, but were determined to join their arms to those of Great Britain and to share their fortune; so, consequently, with a less generous people than Americans they would be made to share the same fate, and be compelled to retire along with them beyond the Lakes. But as we prefer peace to a state of warfare, as we consider them as a deluded people; as we persuade ourselves that they are convinced, from experience, of their error in taking up the hatchet against us, and that their true interest and safety must now depend upon our friendship. As the country is large enough to contain us all; and as we are disposed to be kind to them and to partake of their trade, we will from these considerations and from motives of compassion, draw a veil over what is past and establish a boundary line between them and us beyond which we will endeavor to restrain our people from hunting or settling, and within which they shall not come, but for the purposes of trading, treating, or other business unexceptionable in its nature.

In establishing this line, in the first instance, care should be taken neither to yield nor to grasp at too much. But to endeavor to impress the Indians with an idea of the generosity of our disposition to accommodate them, and with the necessity we are under, of providing for our warriors, our young people who are growing up, and strangers who are coming from other countries to live among us. And if they should make a point of it, or appear dissatisfied at the line we may find it necessary to establish, compensation should be made them for their claims within it.

It is needless for me to express more explicitly because the tendency of my observations evinces it is my opinion that if the legislature of the state of New York should insist upon expelling the Six Nations4 from all the country they inhabited previous to the war, within their territory (as General Schuyler seems to be apprehensive of) that it will end in another Indian war. I have every reason to believe from my inquiries, and the information I have received, that they will not suffer their country (if it was our policy to take it before we could settle it) to be wrested from them without another struggle. That they would compromise for a part of it I have very little doubt, and that it would be the cheapest way of coming at it, I have no doubt at all. The same observations, I am persuaded, will hold good with respect to Virginia, or any other state which has powerful tribes of Indians on their frontiers; and the reason of my mentioning New York is because General Schuyler has expressed his opinion of the temper of its legislature; and because I have been more in the way of learning the sentiments of the Six Nations than of any other tribes of Indians on this subject.

The limits being sufficiently extensive (in the New Country)5 to comply with all the engagements of government and to admit such emigrations as may be supposed to happen within a given time not only from the several states of the Union but from foreign countries, and moreover of such magnitude as to form a distinct and proper government; a proclamation, in my opinion, should issue, making it felony (if there is power for the purpose and if not imposing some very heavy restraint) for any person to survey or settle beyond the line; and the officers commanding the frontier garrison should have pointed and peremptory orders to see that the proclamation is carried into effect.6

Measures of this sort would not only obtain peace from the Indians, but would, in my opinion, be the surest means of preserving it. It would dispose of the land to the best advantage, people the country progressively, and check land jobbing and monopolizing (which is now going forward with great avidity) while the door would be open, and the terms known for everyone to obtain what is reasonable and proper for himself upon legal and constitutional ground.

Every advantage that could be expected or even wished for would result from such a mode of procedure: our settlements would be compact, government well established, and our barrier formidable, not only for ourselves but against our neighbors, and the Indians as has been observed in General Schuyler’s letter will ever retreat as our settlements advance upon them and they will be as ready to sell, as we are to buy. That it is the cheapest as well as the least distressing way of dealing with them, none who are acquainted with the nature of Indian warfare, and has ever been at the trouble of estimating the expense of one, and comparing it with the cost of purchasing their lands, will hesitate to acknowledge.

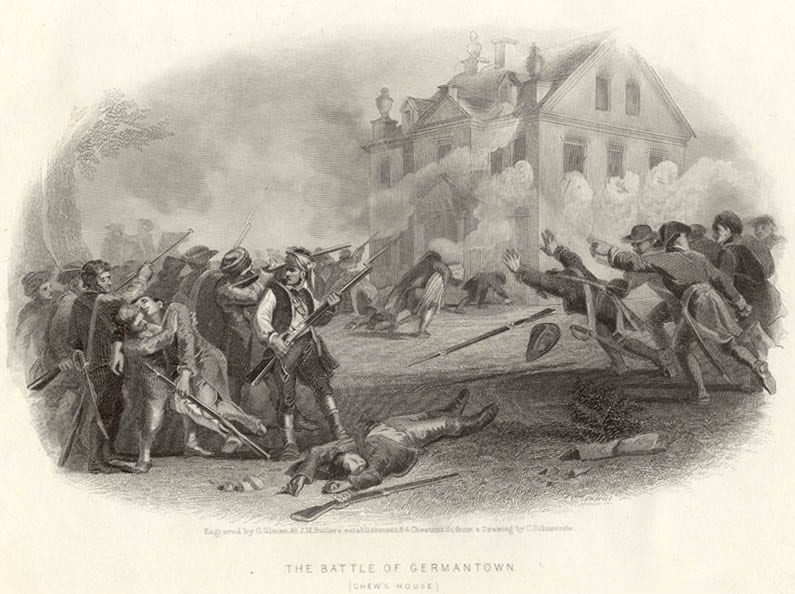

Unless some such measures as I have been taking the liberty of suggesting are speedily adopted one of two capital evils, in my opinion, will inevitably result, and is near at hand; either that the settling, or rather overspreading the western country will take place by a parcel of banditti, who will bid defiance to all authority while they are skimming and disposing of the cream of the country at the expense of many suffering officers and soldiers who have fought and bled to obtain it, and are now waiting the decision of Congress to point them to the promised reward of their past dangers and toils; or a renewal of hostilities with the Indians, brought about more than probably, by this very means.

How far agents for Indian affairs are indispensably necessary I shall not take upon me to decide; but if any should be appointed, their powers in my opinion should be circumscribed, accurately defined, and themselves rigidly punished for every infraction of them. A recurrence to the conduct of these people under the British administration of Indian affairs will manifest the propriety of this caution, as it will there be found, that self-interest was the principle by which their agents were actuated; and to promote this by accumulating lands and passing large quantities of goods through their hands, the Indians were made to speak any language they pleased by their representation; were pacific or hostile as their purposes were most likely to be promoted by the one or the other. No purchase under any pretense whatever should be made by any other authority than that of the sovereign power, or the legislature of the state in which such lands may happen to be. Nor should the agents be permitted directly or indirectly to trade; but to have a fixed, and ample salary allowed them as a full compensation for their trouble.

Whether in practice the measure may answer as well as it appears in theory to me, I will not undertake to say; but I think, if the Indian trade was carried on, on government acc[oun]t, and with no greater advance than what would be necessary to defray the expense and risk, and bring in a small profit, that it would supply the Indians upon much better terms than they usually are; engross their trade, and fix them strongly in our interest; and would be a much better mode of treating them than that of giving presents; where a few only are benefitted by them. I confess there is a difficulty in getting a man, or set of men, in whose abilities and integrity there can be a perfect reliance; without which, the scheme is liable to such abuse as to defeat the salutary ends which are proposed from it. At any rate, no person should be suffered to trade with the Indians without first obtaining a license, and giving security to conform to such rules and regulations as shall be prescribed; as was the case before the war.

In giving my sentiments in the month of May last (at the request of a committee of Congress) on a peace establishment,7 I took the liberty of suggesting the propriety, which in my opinion there appeared, of paying particular attention to the French and other settlers at Detroit and other parts within the limits of the western country; the perusal of a late pamphlet entitled “Observations on the Commerce of the American States with Europe and the West Indies”8 impresses the necessity of it more forcibly than ever on my mind. The author of that piece strongly recommends a liberal change in the government of Canada, and though he is too sanguine in his expectations of the benefits arising from it, there can be no doubt of the good policy of the measure. It behooves us therefore to counteract them, by anticipation. These people [Native Americans] have a disposition toward us susceptible of favorable impressions; but as no arts will be left unattempted by the British to withdraw them from our interest, the present moment should be employed by us to fix them in it, or we may lose them forever; and with them, the advantages or disadvantages consequent of the choice they may make. From the best information and maps of that country, it would appear that from the mouth of the Great Miami River which empties into the Ohio to its confluence with the Mad River, thence by a line to the Miami Fort and Village on the other Miami River which empties into Lake Erie, and thence by a line to include the settlement of Detroit would, with Lake Erie to the northward, Pennsylvania to the eastward, and the Ohio to the southward form a government sufficiently extensive to fulfill all the public engagements, and to receive moreover a large population by emigrants, and to confine the settlement of the new states within these bounds would, in my opinion, be infinitely better even supposing no disputes were to happen with the Indians and that it was not necessary to guard against those other evils which have been enumerated than to suffer the same number of people to roam over a country of at least 500,000 square miles contributing nothing to the support, but much perhaps to the embarrassment of the federal government. . . .

At first view, it may seem a little extraneous, when I am called upon to give an opinion upon the terms of a peace proper to be made with the Indians, that I should go into the formation of new states; but the settlement of the western country and making a peace with the Indians are so analogous that there can be no definition of the one without involving considerations of the other. For I repeat it, again, and I am clear in my opinion, that policy and economy point very strongly to the expediency of being upon good terms with the Indians, and the propriety of purchasing their lands in preference to attempting to drive them by force of arms out of their country; which as we have already experienced is like driving the wild beasts of the forest which will return [to] us soon as the pursuit is at an end and fall perhaps on those that are left there; when the gradual extension of our settlements will as certainly cause the savage as the wolf to retire; both being beasts of prey though they differ in shape. In a word, there is nothing to be obtained by an Indian war but the soil they live on, and this can be had by purchase at less expense, and without that bloodshed, and those distresses which helpless women and children are made partakers of in all kinds of disputes with them. . . .

- 1. Philip Schuyler (1733–1804) of New York

- 2. The Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolutionary War was signed September 3, 1783. Washington referred to the preliminary version of the treaty negotiated in 1782.

- 3. In spite of.

- 4. The Iroquois, or Haudenosaunee, most of whom sided with the British during the Revolutionary War.

- 5. Land outside the original thirteen colonies awarded to the United States in the Treaty of Paris.

- 6. Compare these policies with those announced by King George III in 1763 (Document 5).

- 7. The military force maintained in peacetime.

- 8. John Holroyd, Earl of Sheffield, Observations on the Commerce of the American States with Europe and the West Indies . . . (Philadelphia: R. Bell, 1783).

Farewell Orders to the Armies of the United States

November 02, 1783

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.