No related resources

Introduction

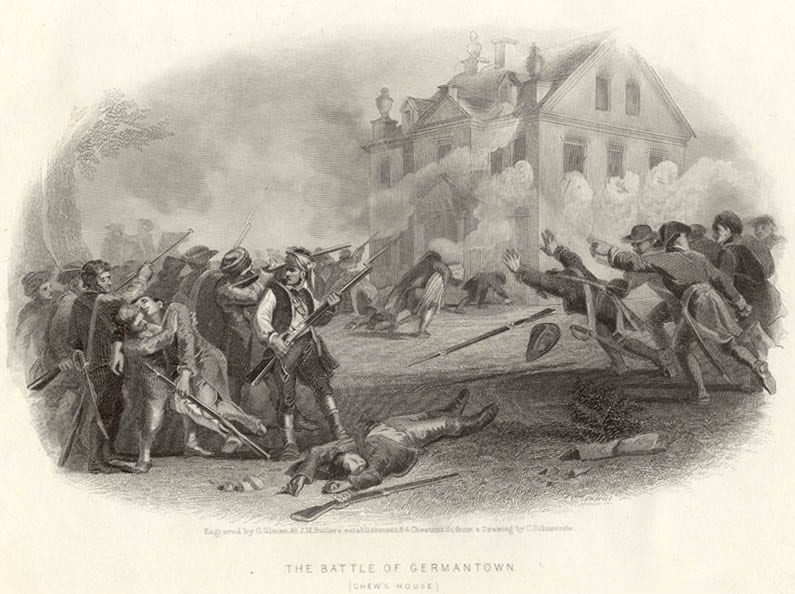

George Washington’s failure to prevent the British army from seizing Philadelphia guided his decision to make Valley Forge the site of the Continental Army’s 1777–1778 winter encampment. Less than twenty miles from the captured capital, it was close enough to curtail British movement in the Pennsylvania countryside but distant enough to diminish the chances his army would fall victim to a surprise attack. Its ridgelines and streams made it easily defensible, and its relative remoteness from settled areas saved any one group of civilians from the burden of living beside an army that, on arrival, had about 12,000 men. The neat rows of log huts ordered built by Washington contained nearly as many people as Charleston—the fourth largest city in the United States.

Although fifth in size, Valley Forge ranked first in terms of hunger. While an excellent harvest satisfied the appetites of most Americans, the Continental Army’s poor logistics meant that soldiers learned to content themselves, as Private Joseph Plumb Martin (1760–1850) wryly remembered, with meals consisting of “a leg of nothing and no turnips.”

Not long after his arrival at Valley Forge, this seventeen-year-old soldier found himself assigned to the quartermaster, who made him a member of a foraging party based twenty miles to the west of the encampment. Here it was his duty to engage in what he described as the “plundering” of civilians’ corn, livestock, and other provisions so that soldiers back at Valley Forge could spend fewer nights eating flour and water baked into “firecake.” For Martin, who first enlisted in 1776 as a 15-year-old from Milford, Connecticut, interacting with Pennsylvanians and serving at the start of the supply chain made this a plum assignment. “We fared much better than I had ever done in the army before,” he later recollected, for “we had very good provisions all winter and generally enough of them.”

During the course of the war Martin rose to the rank of sergeant. He fought at numerous battles, including Monmouth and Yorktown, before his discharge from the army in 1783. He later helped establish the town of Prospect, Maine, where he married, had five children, wrote his Revolutionary War memoir, and lived until the age of 89.

Source: [Joseph Plumb Martin,] A Narrative of Some of the Adventures, Dangers, and Sufferings of a Revolutionary Soldier…. (Hallowell, Maine, 1830), 75–83.

The army… marched for the Valley Forge in order to take up our winter quarters. We were now in a truly forlorn condition—no clothing, no provisions, and as disheartened as need be. We arrived, however, at our destination a few days before Christmas. Our prospect was indeed dreary. In our miserable condition, to go into the wild woods and build us habitations to stay (not to live) in, in such a weak, starved, and naked condition, was appalling in the highest degree, especially to New Englanders, unaccustomed to such kind of hardships at home. However, there was no remedy—no alternative but this or dispersion. But dispersion, I believe, was not thought of—at least, I did not think of it. We had engaged in the defense of our injured country and were willing, nay, we were determined to persevere as long as such hardships were not altogether intolerable…. But we were now absolutely in danger of perishing, and that too, in the midst of a plentiful country. We then had but little, and often nothing to eat for days together; but now we had nothing and saw no likelihood of any betterment of our condition. Had there fallen deep snows (and it was the time of year to expect them) or even heavy and long rainstorms, the whole army must inevitably have perished. Or had the enemy, strong and well provided as he then was, thought fit to pursue us, our poor emaciated carcasses must have “strewed the plain.” But a kind and holy Providence took more notice and better care of us than did the country in whose service we were wearing away our lives by piecemeal.

We arrived at the Valley Forge in the evening. It was dark; there was no water to be found, and I was perishing with thirst, I searched for water till I was weary, and came to my tent without finding any. Fatigue and thirst, joined with hunger, almost made me desperate. I felt at that instant as if I would have taken victuals or drink from the best friend I had on earth by force. I am not writing fiction, all are sober realities. Just after I arrived at my tent, two soldiers, whom I did not know, passed by. They had some water in their canteens which they told me they had found a good distance off, but could not direct me to the place as it was very dark. I tried to beg a draught of water from them but they were as rigid as Arabs. At length I persuaded them to sell me a drink for three pence, Pennsylvania currency, which was every cent of property I could then call my own; so great was the necessity I was then reduced to.

I lay here two nights and one day, and had not a morsel of anything to eat all the time, save half of a small pumpkin, which I cooked by placing it upon a rock, the skin side uppermost, and making a fire upon it. By the time it was heat through I devoured it with as keen an appetite as I should a pie made of it at some other time.

The second evening after our arrival here I was warned to be ready for a two days command. I never heard a summons to duty with so much disgust before or since, as I did that. How I could endure two days more fatigue without nourishment of some sort I could not tell, for I heard nothing said about “provisions.” However, in the morning at roll call I was obliged to comply. I went to the parade where I found a considerable number, ordered upon the same business, whatever it was. We were ordered to go to the quartermaster general and receive from him our final orders. We accordingly repaired to his quarters, which was about three miles from camp; here we understood that our destiny was to go into the country on a foraging expedition, which was nothing more nor less than to procure provisions from the inhabitants for the men in the army and forage for the poor perishing cattle belonging to it, at the point of the bayonet. We stayed at the quartermaster general’s quarters till some time in the afternoon, during which time a beef creature was butchered for us. I well remember the fine stuff it was; it was quite transparent. I thought at the time what an excellent lantern it would make. I was, notwithstanding, very glad to get some of it, bad as it looked…. We were then divided into several parties and sent off upon our expedition.

Our party consisted of a lieutenant, a sergeant, a corporal and eighteen privates. We marched till night when we halted and took up our quarters at a large farmhouse. The lieutenant, attended by his waiter, took up his quarters for the night in the hall with the people of the house, we were put into the kitchen; we had a snug room and a comfortable fire, and we began to think about cooking some of our fat beef. One of the men proposed to the landlady to sell her a shirt for some sauce. She very readily took the shirt, which was worth a dollar at least. She might have given us a mess of sauce, for I think she would not have suffered poverty by so doing, as she seemed to have a plenty of all things. After we had received the sauce, we went to work to cook our suppers. By the time it was eatable the family had gone to rest. We saw where the woman went into the cellar, and, she having left us a candle, we took it into our heads that little good cider would not make our supper relish any the worse; so some of the men took the water pail and drew it full of excellent cider, which did not fail to raise our spirits considerably. Before we lay down the man who sold the shirt, having observed that the landlady had flung it into a closet, took a notion to repossess it again. We marched off early in the morning before the people of the house were stirring, consequently did not know or see the woman’s chagrin at having been overreached by the soldiers.

This day we arrived at Milltown, or Downingtown, a small village halfway between Philadelphia and Lancaster, which was to be our quarters for the winter. It was dark when we had finished our day’s march. There was a commissary and a wagon master general to regulate the conduct of the wagoners and direct their motions. The next day after our arrival at this place we were put into a small house in which was only one room, in the center of the village. We were immediately furnished with rations of good and wholesome beef and flour, built us up some births to sleep in, and filled them with straw, and felt as happy as any other pigs that were no better off than ourselves….

The first expedition I undertook in my new vocation, was a foraging cruise. I was ordered off into the country in a party consisting of a corporal and six men. What our success was I do not now remember; but I well remember the transactions of the party in the latter part of the journey. We were returning to our quarters on Christmas afternoon, when we met three ladies, one a young married woman with an infant in her arms, the other two were maidens… [or at least] they passed for such. They were all comely, particularly one of them; she was handsome. They immediately fell into familiar discourse with us—were very inquisitive like the rest of the sex—asked us a thousand questions respecting our business, where we had been and where going, etc. After we had satisfied their curiosity, or at least had endeavored to do so, they told us that they (that is, the two youngest) lived a little way on our road in a house which they described, desired us to call in and rest ourselves a few minutes, and said they would return as soon as they had seen their sister and babe safe[ly] home.

As for myself, I was very unwell, occasioned by a violent cold I had recently taken, and I was very glad to stop a short time to rest my bones. Accordingly, we stopped at the house described by the young ladies, and in a few minutes they returned as full of chat as they were when we met them in the road. After a little more information respecting our business, they proposed to us to visit one of their neighbors, against whom it seemed they had a grudge, and upon whom they wished to wreak their vengeance through our agency. To oblige the ladies we undertook to obey their injunctions. They very readily agreed to be our guides as the way lay across fields and pastures full of bushes. The distance was about half a mile…. The girls went with us until we came in sight of the house. We concluded we could do no less than fulfill our engagements with them, so we went into the house, the people of which, appeared to be genuine Pennsylvania farmers, and very fine folks.

We all now began to relent, and after telling them our business, we concluded that if they would give us a canteen (which held about a quart) full of whiskey and some bread and cheese, we would depart without any further exactions. To get rid of us, doubtless, the man of the house gave us our canteen of whiskey, and the good woman gave us a fine loaf of wheaten flour bread and the whole of a small cheese, and we raised the siege and departed. I was several times afterwards at this house, and was always well treated. I believe the people did not recollect me, and I was glad they did not, for when I saw them I had always a twinge or two of conscience for thus dissembling with them at the instigation of persons who certainly were no better than they should be, or they would not have employed strangers to glut their vengeance upon innocent people; innocent at least as it respected us. But after all, it turned much in their favor. It was in our power to take cattle or horses, hay, or any other produce from them; but we felt that we had done wrong in listening to the tattle of malicious neighbors, and for that cause we refrained from meddling with any property of theirs ever after. So that good came to them out of intended evil.

After we had received our bread, cheese, and whiskey, we struck across the fields into the highway again. It was now nearly sunset, and as soon as we had got into the road, the youngest of the girls, and handsomest and chattiest, overtook us again, riding on horseback with a gallant.[1] As soon as she came up with us, “O here is my little captain again,” said she. (It appeared it was our corporal that attracted her attention.) “I am glad to see you again.” The young man, her sweetheart, did not seem to wish her to be quite so familiar with her “little captain,” and urged on his horse as fast as possible. But female policy is generally too subtle for the male’s, and she exhibited a proof of it, for they had scarcely passed us when she slid from the horse upon her feet, into the road, with a shriek as though some frightful accident had happened to her. There was nothing handy to serve as a horseblock, so the “little captain” must take her in his arms and set her upon her horse again, much, I suppose, to their mutual satisfaction—but not so to her gallant, who, as I thought, looked rather grum….[2]

I shall not relate all the minute transactions which passed while I was on this foraging party, as it would swell my narrative to too large a size. I will, however, give the reader a brief account of some of my movements that I may not leave him entirely ignorant how I spent my time. We fared much better than I had ever done in the army before, or ever did afterwards. We had very good provisions all winter and generally enough of them. Some of us were constantly in the country with the wagons; we went out by turns and had no one to control us. Our lieutenant scarcely ever saw us or we him; our sergeant never went out with us once, all the time we were there, nor our corporal but once, and that was when he was the “little captain.” When we were in the country we were pretty sure to fare well, for the inhabitants were remarkably kind to us. We had no guards to keep; our only duty was to help load the wagons with hay, corn, meal, or whatever they were to take off, and when they were thus loaded, to keep them company till they arrived at the commissary’s, at Milltown. From thence the articles, whatever they were, were carried to camp in other vehicles, under other guards.

I do not remember that during the time I was employed in this business, which was from Christmas to the latter part of April, ever to have met with the least resistance from the inhabitants, take what we would from their barns, mills, corncribs, or stalls; but when we came to their stables, then look out for the women. Take what horse you would, it was one or the other’s “pony” and they had no other to ride to church; and when we had got possession of a horse we were sure to have half a dozen or more women pressing upon us, until by some means or other, if possible, they would slip the bridle from the horse’s head, and then we might catch him again if we could. They would take no more notice of a charged bayonet than a blind horse would of a cocked pistol. It would answer no purpose to threaten to kill them with the bayonet or musket; they knew as well as we did that we would not put our threats in execution, and when they had thus liberated a horse (which happened but seldom) they would laugh at us and ask us why we did not do as we threatened, kill them, and then they would generally ask us into their houses and treat us with as much kindness as though nothing had happened.

The women of Pennsylvania, taken in general, are certainly very worthy characters; it is but justice, as far as I am concerned, for me to say, that I was always well treated both by them and the men, especially the Friends or Quakers, in every part of the state through which I passed, and that was the greater part of what was then inhabited. But the southern ladies had a queer idea of the Yankees (as they always called the New Englanders). They seemed to think that they were a people quite different from themselves, as indeed they were in many respects. I could mention many things and ways in which they differed, but it is of no consequence; they were clever and that is sufficient. I will, however, mention one little incident, just to show what their conceptions were of us.

I happened once to be with some wagons, one of which was detached from the party. I went with this team as its guard; we stopped at a house, the mistress of which and the wagoner were acquainted. (These foraging teams all belonged in the neighborhood of our quarters.) She had a pretty little female child about four years old. The teamster was praising the child, extolling its gentleness and quietness, when the mother observed that it had been quite cross and crying all day. “I have been threatening,” said she, “to give her to the Yankees.” “Take care,” said the wagoner, “how you speak of the Yankees, I have one of them here with me.” “La!” said the woman, “is he a Yankee? I thought he was a Pennsylvanian. I don’t see any difference between him and other people.”

I have before said that I should not narrate all the little affairs which transpired while I was on this foraging party. But if I pass them all over in silence the reader may perhaps think that I had nothing to do all winter, or at least, that I did nothing, when in truth it was quite the reverse. Our duty was hard, but generally not altogether unpleasant. I had to travel far and near, in cold and in storms, by day and by night, and at all times to run the risk of abuse, if not of injury, from the inhabitants, when plundering them of their property (for I could not, while in the very act of taking their cattle, hay, corn, and grain from them against their wills, consider it a whit better than plundering—sheer privateering). But I will give them the credit of never receiving the least abuse or injury from an individual during the whole time I was employed in this business. I doubt whether the people of New England would have borne it as patiently, their “steady habits”[3] to the contrary notwithstanding.

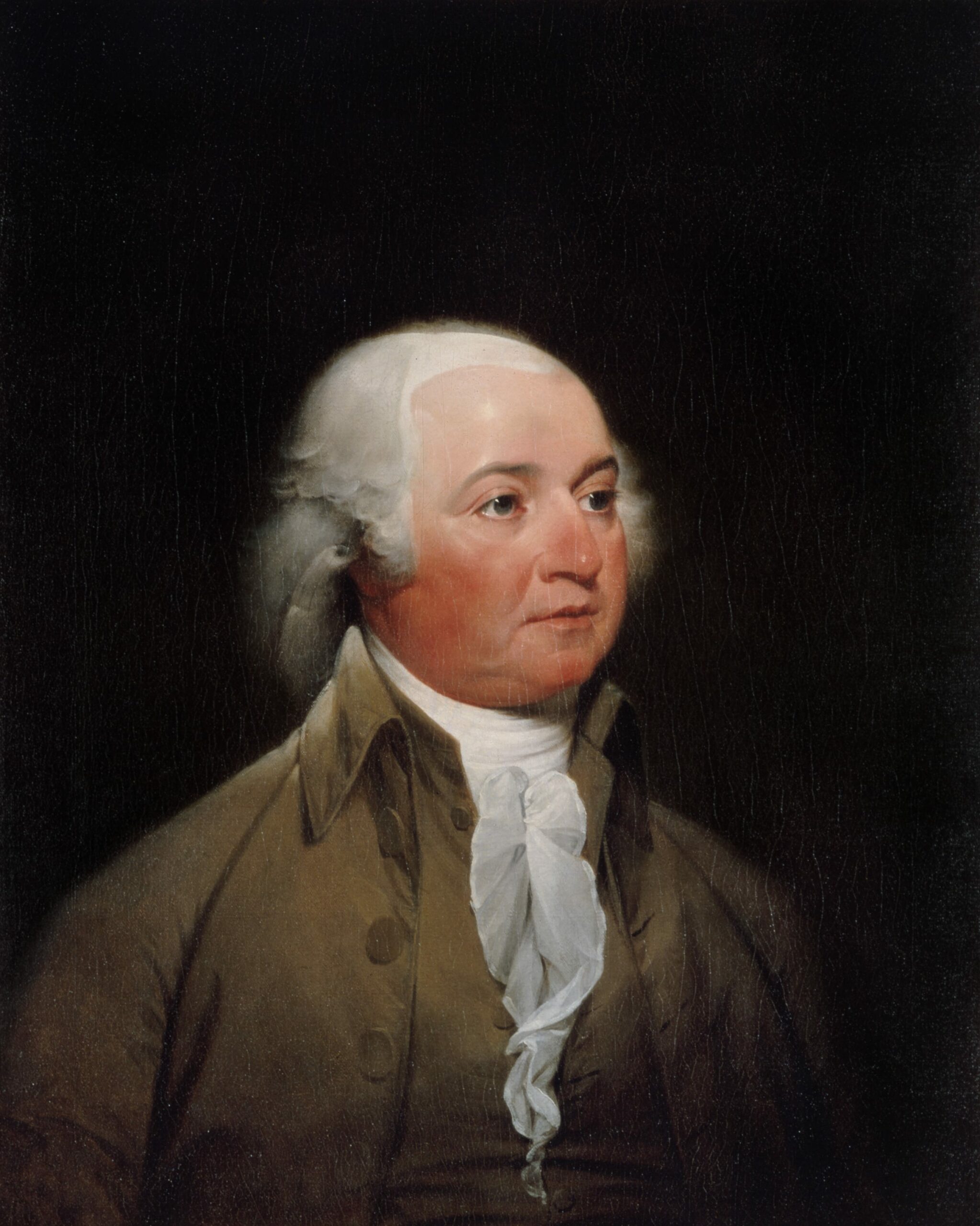

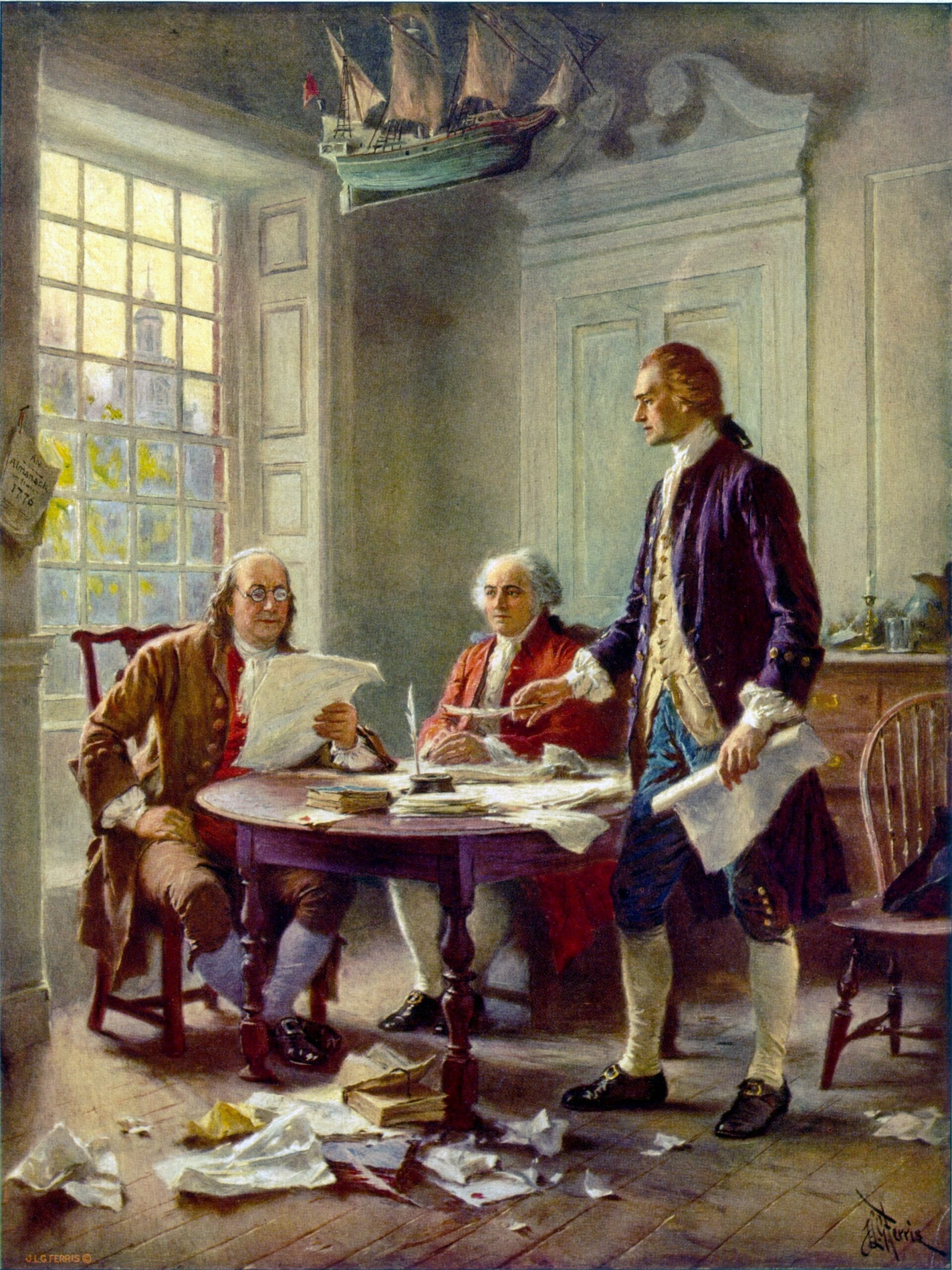

Letter from John Laurens to Henry Laurens (1778)

January 14, 1778

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.