Introduction

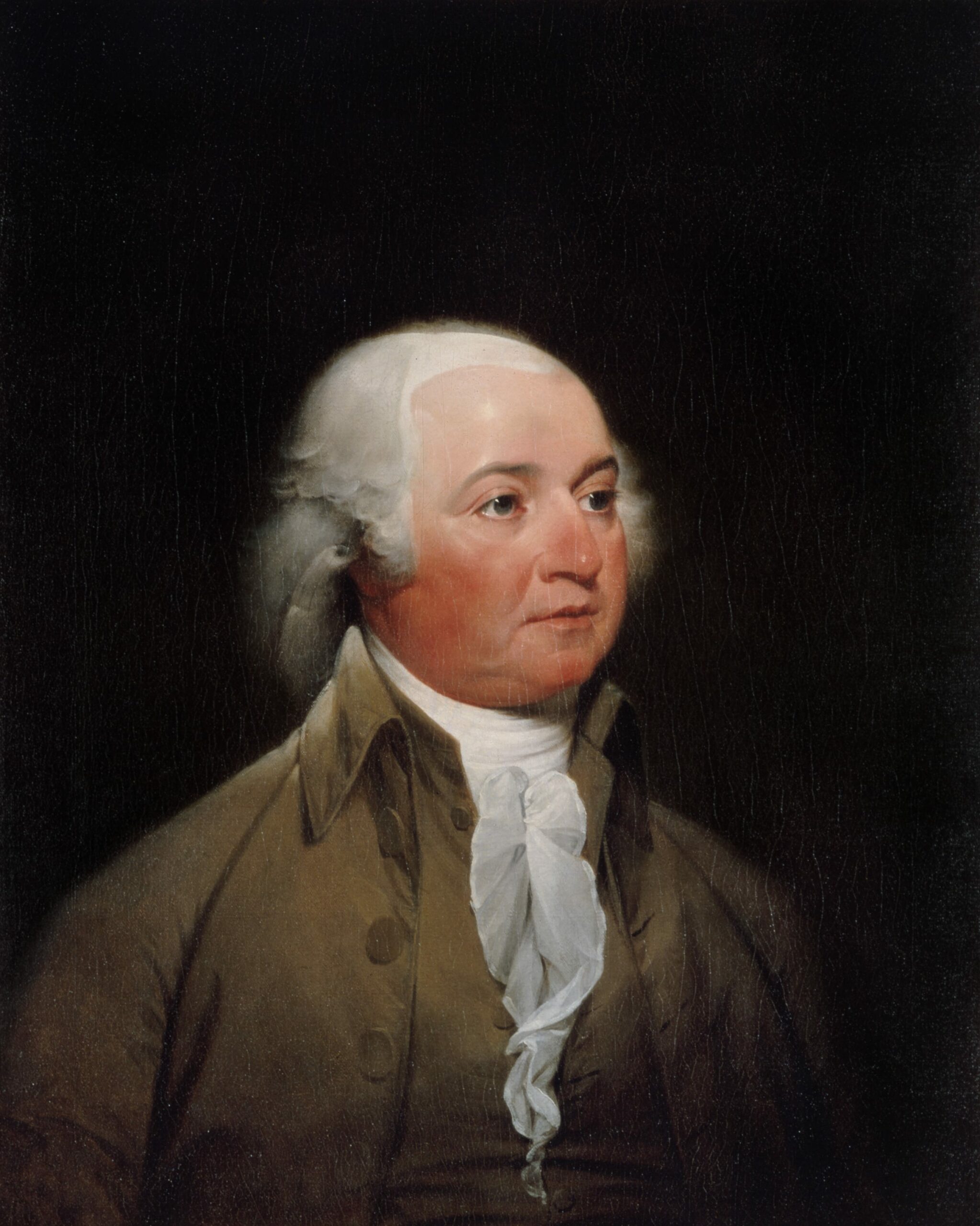

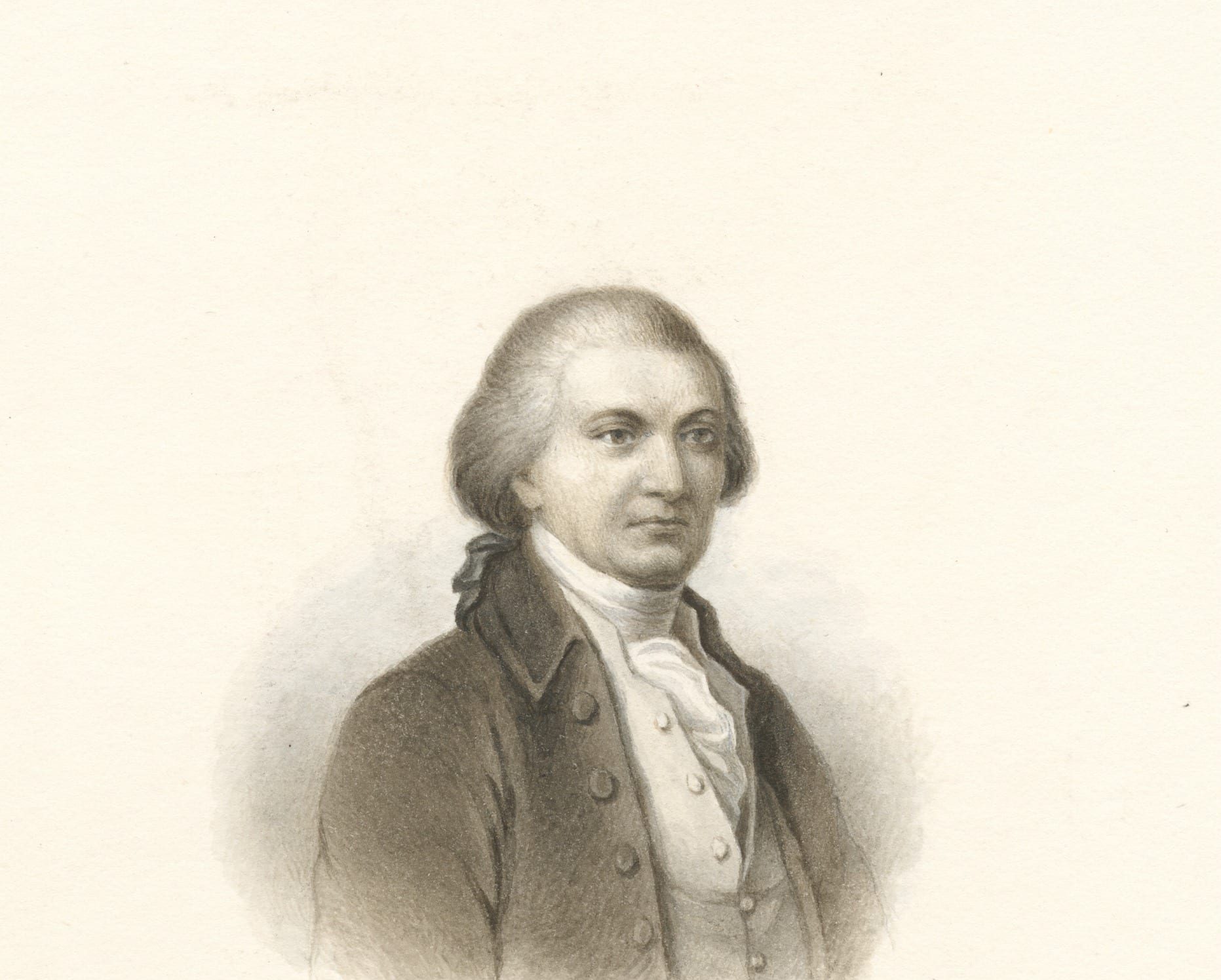

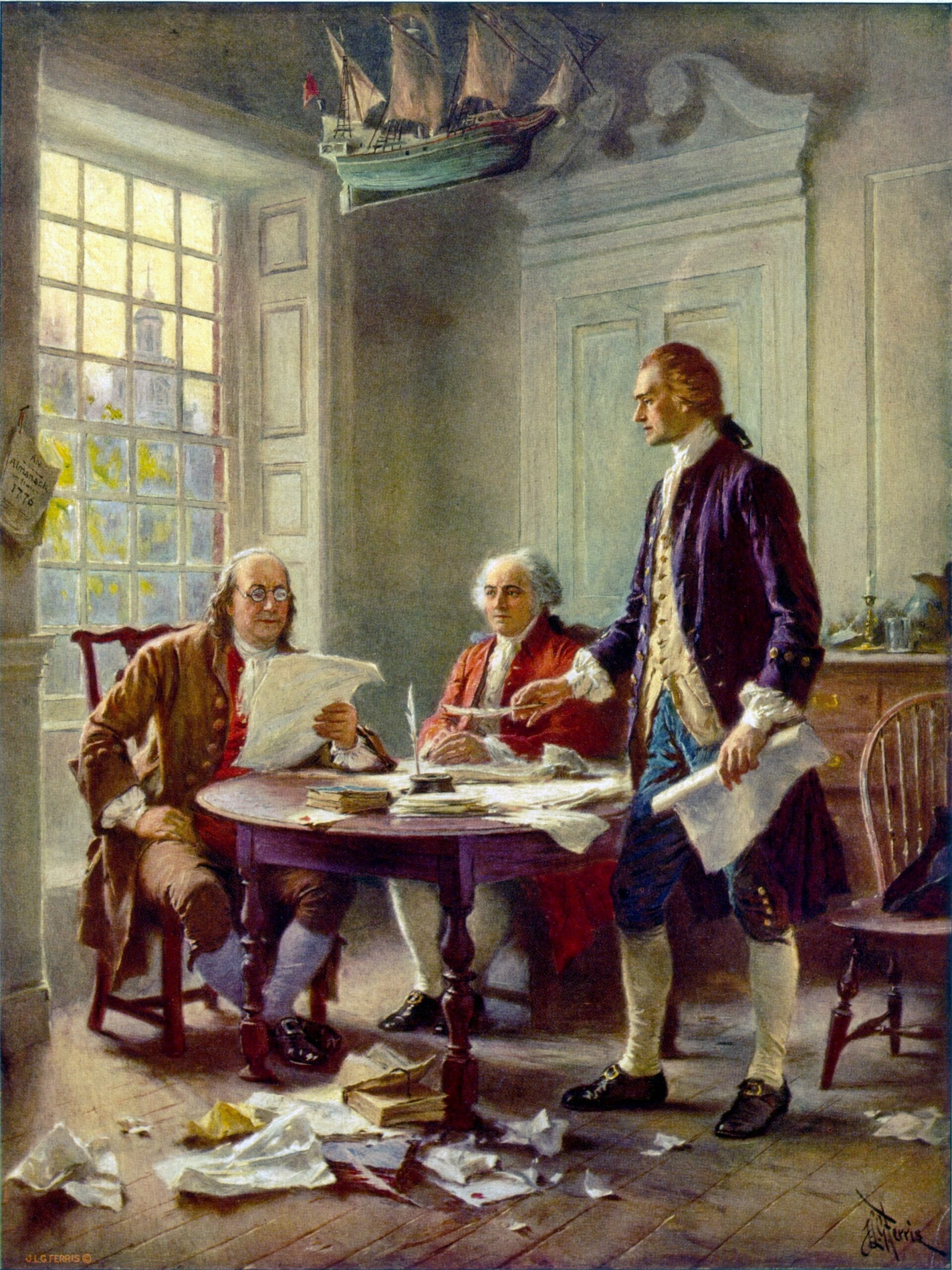

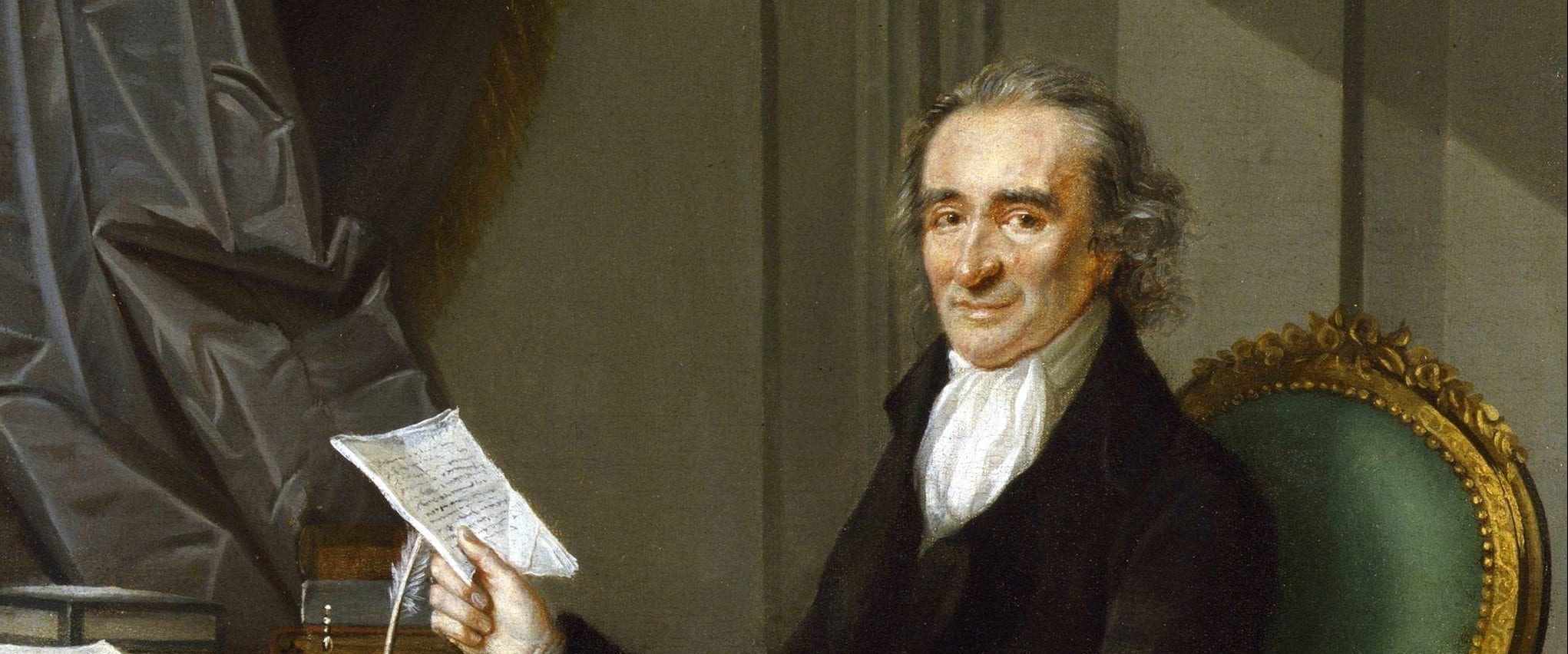

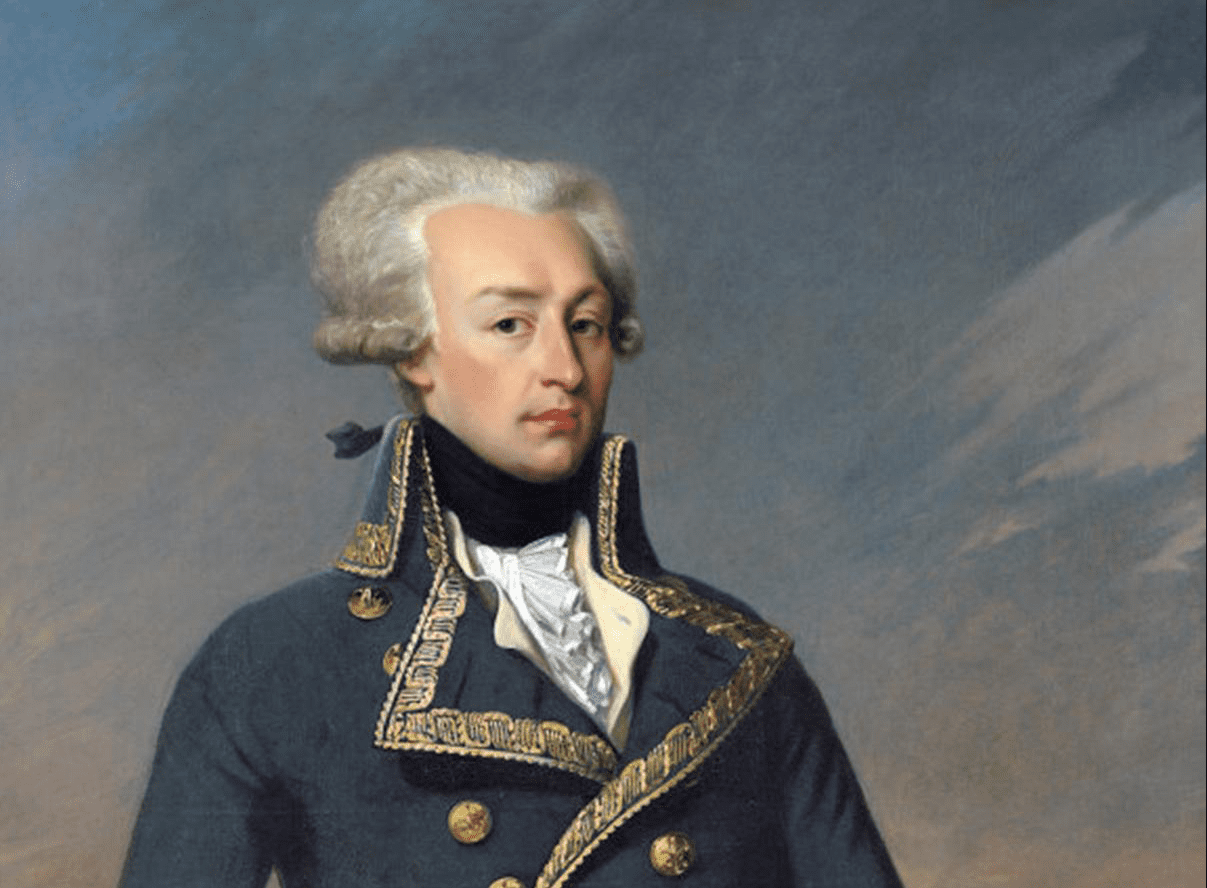

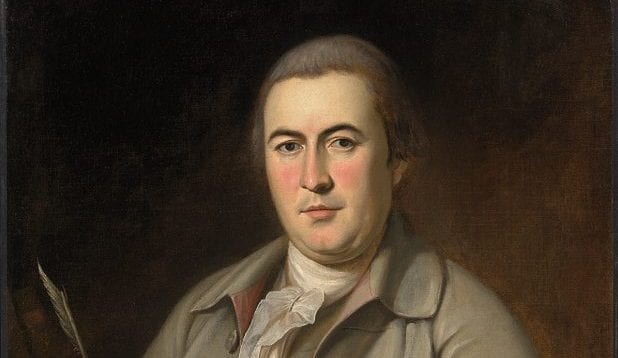

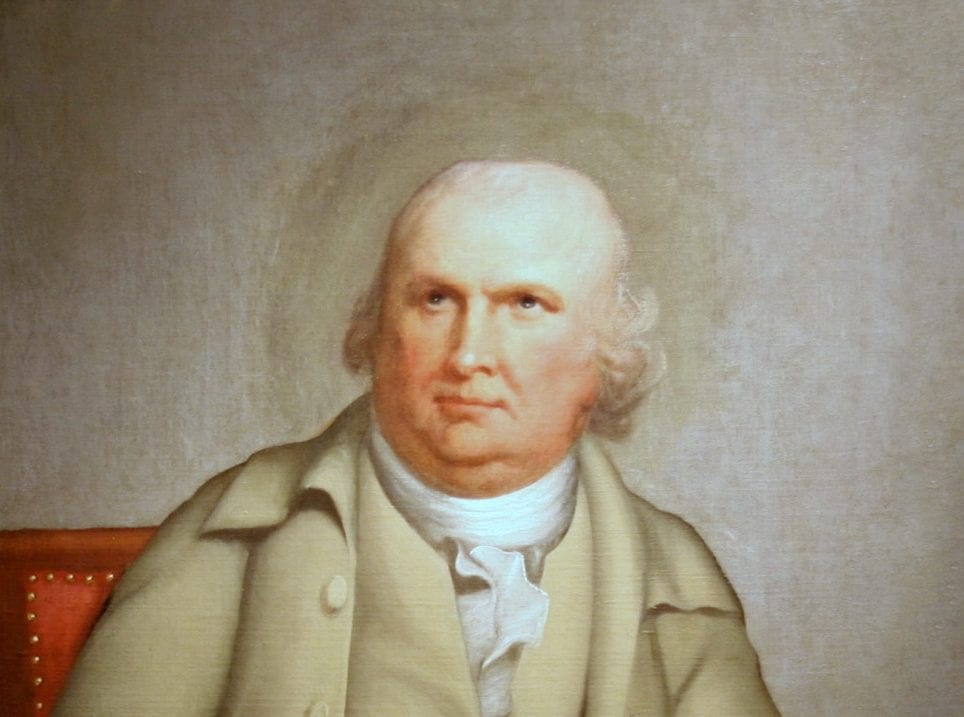

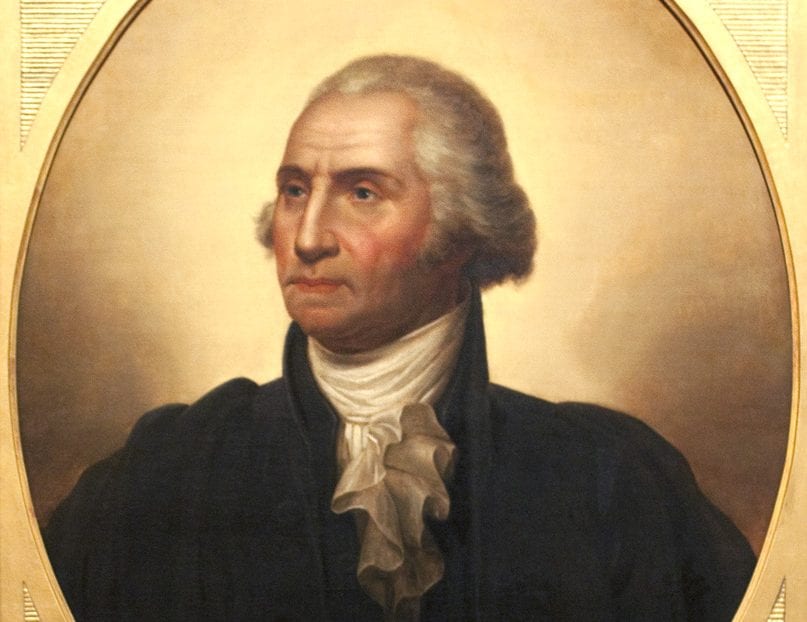

While Thomas Jefferson was the author of some 20,000 letters and kept lengthy records of financial transactions and weather conditions, he published only one book during his lifetime, Notes on the State of Virginia. The essays in this book were written in response to a request from a member of the French diplomatic corps in Philadelphia in 1780 seeking information about the thirteen American states. Jefferson, serving as the governor of Virginia at this time, submitted a response on behalf of his state. The collection of essays was expanded and revised over time and published in book form in 1785.

In this essay, on public income and expenses, Jefferson condemned the wastefulness of war and noted the dangers presented by a standing army, stances that were consistent themes throughout the years of his public service. While Jefferson preferred a nation of virtuous farmers, his countrymen were addicted to commerce, and therefore some naval power was required to protect American trade. Jefferson believed that America’s geographic exceptionalism allowed it to defend its interests in a manner distinctly different from the Old World. With its unique geographic position America could maintain a smaller navy with immediate access to ports for repairs and resupply while its enemies, with vastly superior fleets, operated at a disadvantage in having to cross thousands of miles of ocean and having to rely on supplies from the New World.

Jefferson was constantly seeking options short of war or alternatives to traditional methods of projecting force—options appropriate for a political order set apart, literally and figuratively, from the rest of the world. An added benefit of America’s geographic isolation was that its small fleet, operating strictly in a defensive manner, would be incapable of serving as a tool for imperialism, a practice Jefferson abhorred. This essay anticipated many of the foreign and defense policies Jefferson implemented as the nation’s third president.

—Stephen F. Knott

Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, Query 22 (London: John Stockdale, 1785), available at https://teachingamericanhistory.org/bc2z.

… To this estimate of our abilities, let me add a word as to the application of them, if, when cleared of the present contest, and of the debts with which that will charge us, we come to measure force hereafter with any European power. Such events are devoutly to be deprecated. Young as we are, and with such a country before us to fill with people and with happiness, we should point in that direction the whole generative force of nature, wasting none of it in efforts of mutual destruction. It should be our endeavor to cultivate the peace and friendship of every nation, even of that which has injured us most, when we shall have carried our point against her. Our interest will be to throw open the doors of commerce, and to knock off all its shackles, giving perfect freedom to all persons for the vent of whatever they may choose to bring into our ports, and asking the same in theirs. Never was so much false arithmetic employed on any subject, as that which has been employed to persuade nations that it is their interest to go to war. Were the money which it has cost to gain, at the close of a long war, a little town, or a little territory, the right to cut wood here, or to catch fish there, expended in improving what they already possess, in making roads, opening rivers, building ports, improving the arts, and finding employment for their idle poor, it would render them much stronger, much wealthier and happier. This I hope will be our wisdom. And, perhaps, to remove as much as possible the occasions of making war, it might be better for us to abandon the ocean altogether, that being the element whereon we shall be principally exposed to jostle with other nations: to leave to others to bring what we shall want, and to carry what we can spare. This would make us invulnerable to Europe, by offering none of our property to their prize, and would turn all our citizens to the cultivation of the earth; and, I repeat it again, cultivators of the earth are the most virtuous and independent citizens. It might be time enough to seek employment for them at sea, when the land no longer offers it. But the actual habits of our countrymen attach them to commerce. They will exercise it for themselves. Wars then must sometimes be our lot; and all the wise can do, will be to avoid that half of them which would be produced by our own follies, and our own acts of injustice; and to make for the other half the best preparations we can. Of what nature should these be? A land army would be useless for offense, and not the best nor safest instrument of defense. For either of these purposes, the sea is the field on which we should meet an European enemy. On that element it is necessary we should possess some power. To aim at such a navy as the greater nations of Europe possess, would be a foolish and wicked waste of the energies of our countrymen. It would be to pull on our own heads that load of military expense, which makes the European laborer go supperless to bed, and moistens his bread with the sweat of his brows. It will be enough if we enable ourselves to prevent insults from those nations of Europe which are weak on the sea, because circumstances exist, which render even the stronger ones weak as to us. Providence has placed their richest and most defenseless possessions at our door; has obliged their most precious commerce to pass as it were in review before us. To protect this, or to assail us, a small part only of their naval force will ever be risked across the Atlantic. The dangers to which the elements expose them here are too well known, and the greater dangers to which they would be exposed at home, were any general calamity to involve their whole fleet. They can attack us by detachment only; and it will suffice to make ourselves equal to what they may detach. Even a smaller force than they may detach will be rendered equal or superior by the quickness with which any check may be repaired with us, while losses with them will be irreparable till too late. A small naval force then is sufficient for us, and a small one is necessary. What this should be, I will not undertake to say. I will only say, it should by no means be so great as we are able to make it. Suppose the million of dollars, or 300,000 pounds, which Virginia could annually spare without distress, to be applied to the creating a navy. A single year’s contribution would build, equip, man, and send to sea a force which should carry 300 guns. The rest of the confederacy, exerting themselves in the same proportion, would equip in the same time 1,500 guns more. So that one year’s contributions would set up a navy of 1,800 guns. The British ships of the line average 76 guns; their frigates 38. Eighteen hundred guns then would form a fleet of 30 ships, 18 of which might be of the line, and 12 frigates. Allowing 8 men, the British average, for every gun, their annual expense, including subsistence, clothing, pay, and ordinary repairs, would be about 1,280 dollars for every gun, or 2,304,000 dollars for the whole. I state this only as one year’s possible exertion, without deciding whether more or less than a year’s exertion should be thus applied….