Introduction

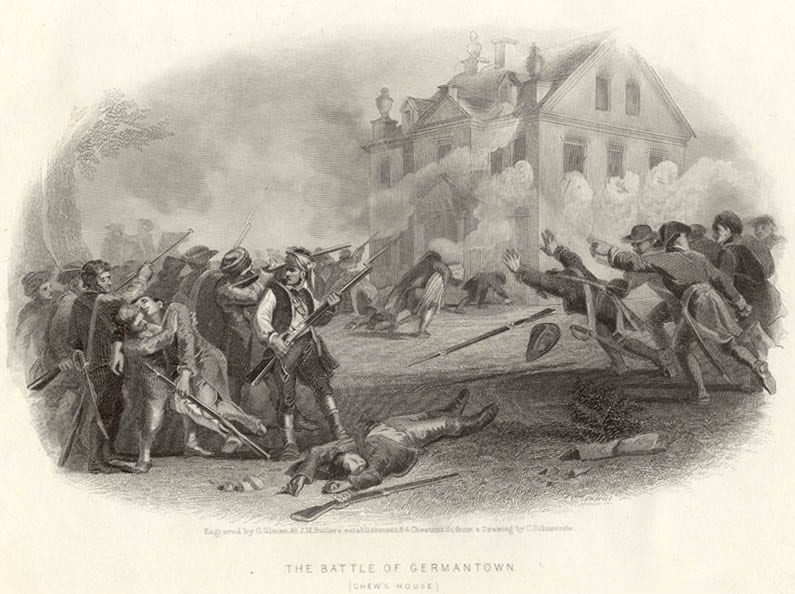

By early 1781 it had become clear that Britain’s southern campaign had produced only mixed results. Initial successes in Georgia and South Carolina were answered in October 1780 by Patriot militiamen at Kings Mountain, just south of the North Carolina border, and then again in January 1781 at the Battle of Cowpens, deep in the South Carolina backcountry, where Continentals under the command of Brigadier General Daniel Morgan (1736–1802) vanquished British and Loyalist troops serving under Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton (1754–1833). In March at Guilford Court House in North Carolina, Lieutenant General Charles Cornwallis (1738–1805) won a “victory” that left one-quarter of his Redcoats wounded, missing, or dead. Back in London, Whig war critic Charles James Fox (1749–1806) roared in the House of Commons that “another such victory would ruin the British army!”

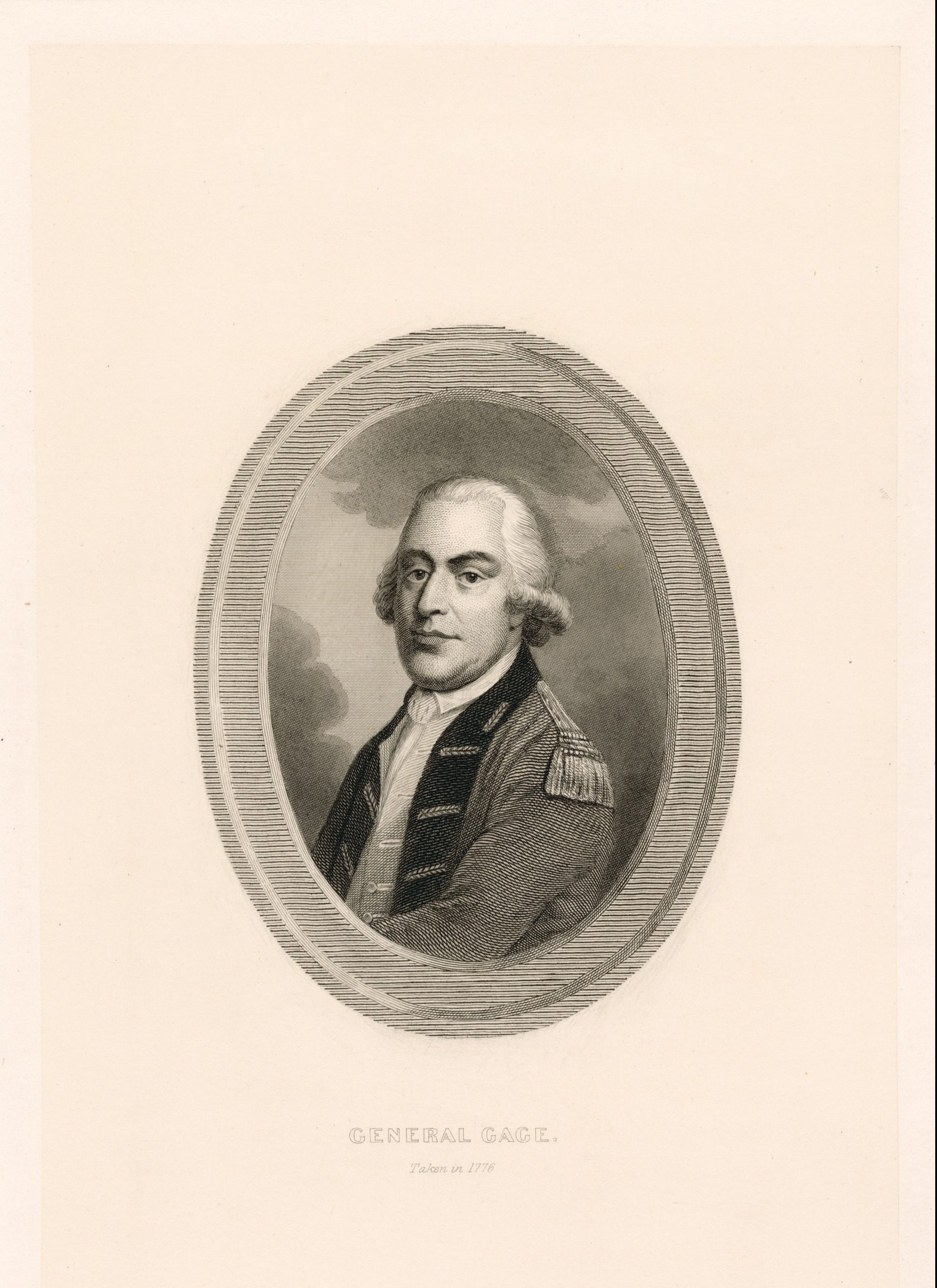

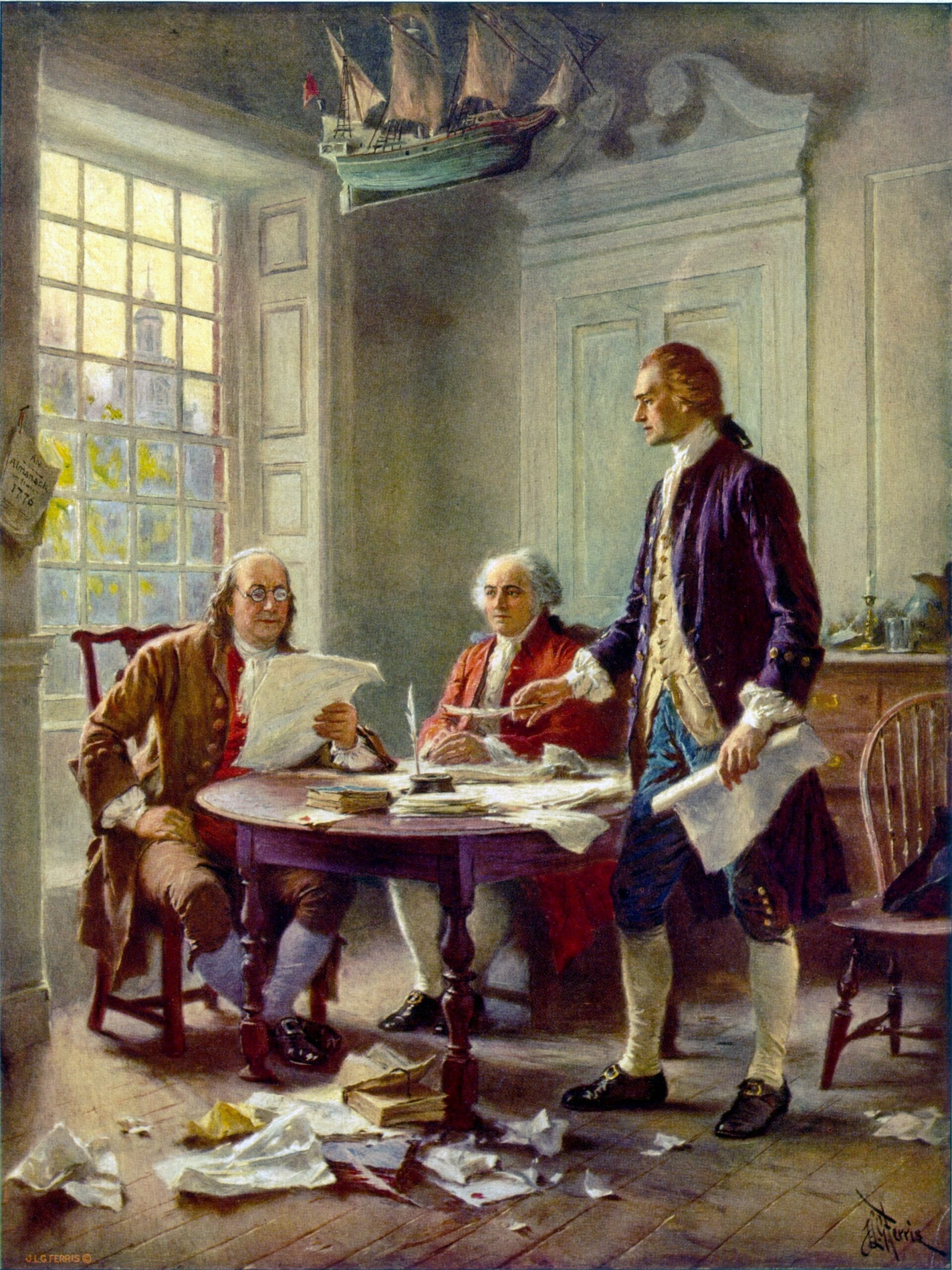

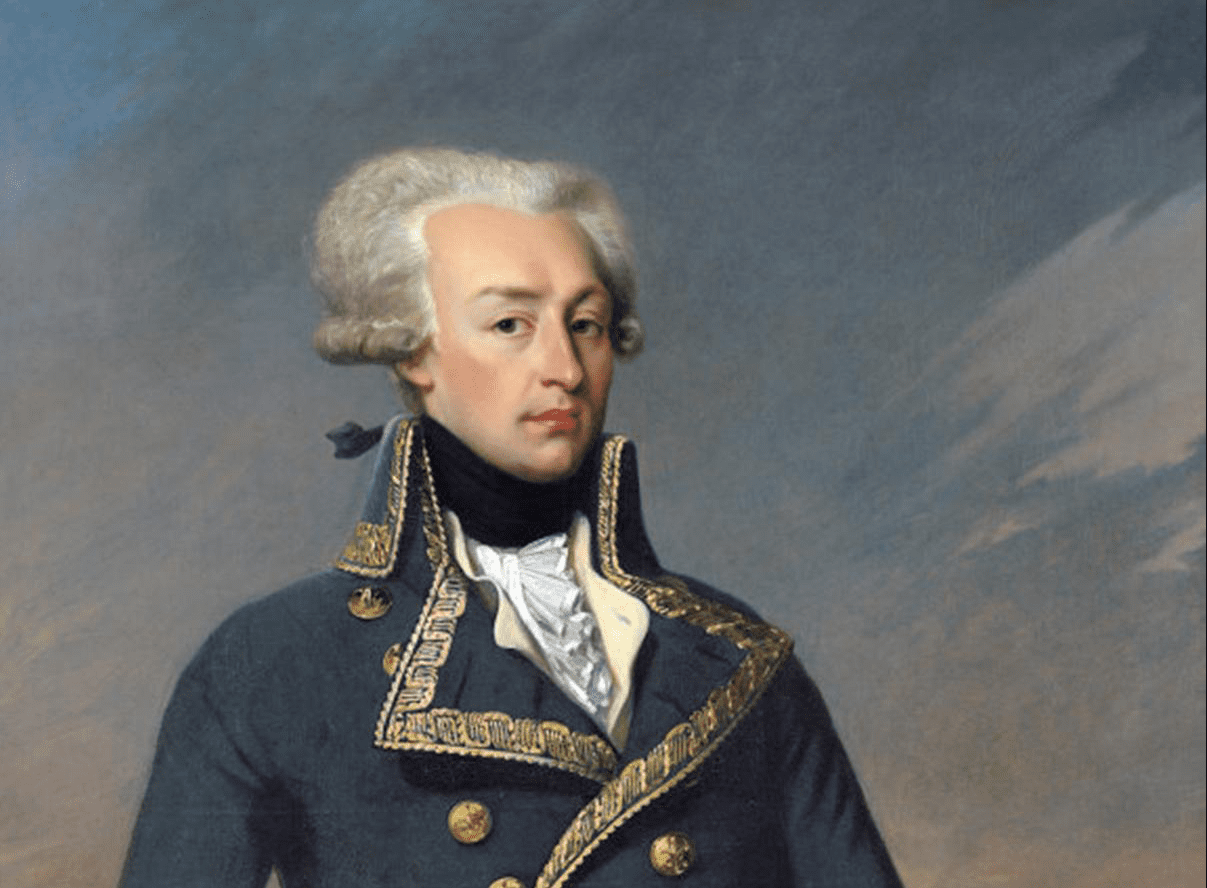

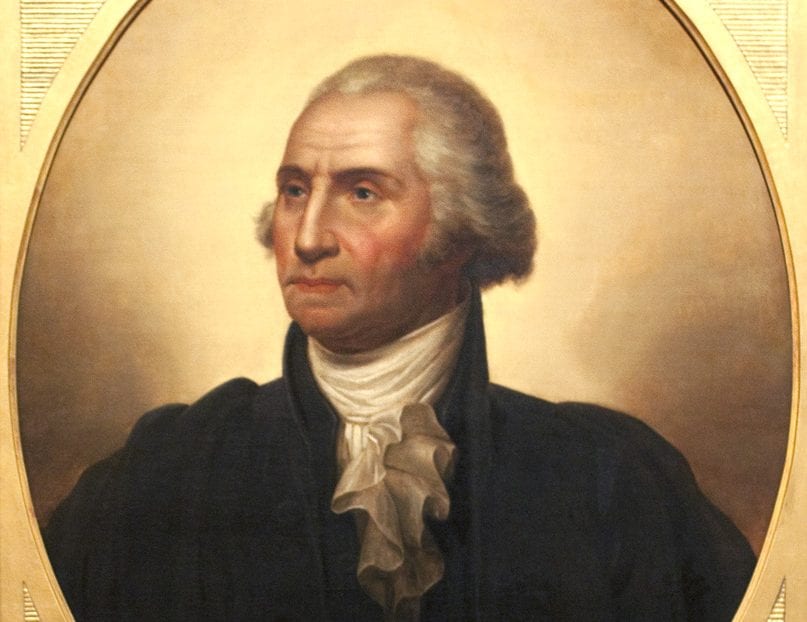

Cornwallis drove north into Virginia, raiding farms and skirmishing intermittently with Continentals commanded by the Marquis de Lafayette (1757–1834) until General Henry Clinton (1730–1795), British commander-in-chief for North America, ordered Cornwallis to fortify a port as a base for naval operations. Lafayette felt bewildered when Cornwallis withdrew to Yorktown on the Virginia Peninsula, exposing his army to possible capture. When George Washington (1732–1799) received news that a French fleet under Admiral de Grasse (1722–1788) had set sail for the Chesapeake, he and French Lieutenant General Rochambeau (1725–1807) decided to march their armies from the vicinity of New York City all the way to Virginia. Leaving behind a small rear detachment to conceal their departure, their combined forces joined Lafayette at Yorktown in mid-September. Cornwallis soon discovered that he was outnumbered and also surrounded—both on land and at sea. After a three-week siege, Cornwallis accepted the inevitable and agreed to capitulate.

Dr. James Thacher (1754–1844), a Massachusetts physician who served as a surgeon in the Continental Army, recorded in his diary a thorough account of the surrender ceremony, but three details seem to have escaped his notice. First, when humiliated British troops filed between the columns of French and American soldiers, they turned their heads toward the French to avert the eyes of the Americans. Noting this, Lafayette ordered his fifes and drums to play “Yankee Doodle.” The tune, originally embraced by Redcoats to mock their American counterparts, now caused them to turn their heads to acknowledge the ragtag army that had helped secure their defeat.

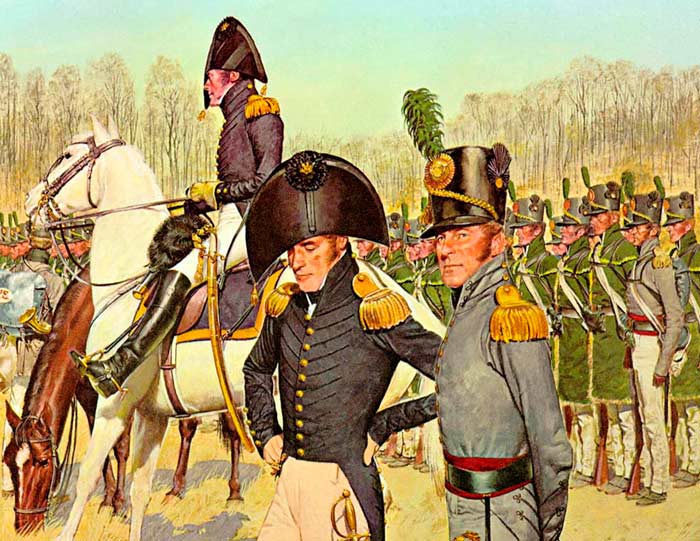

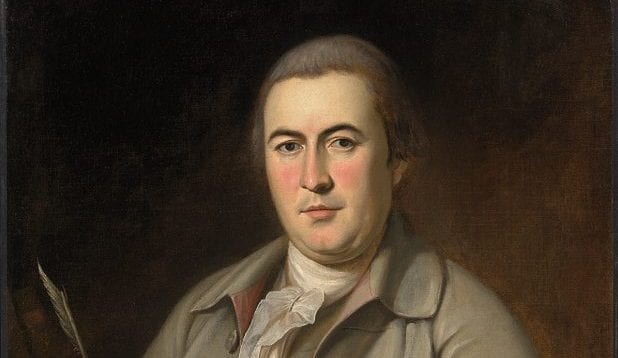

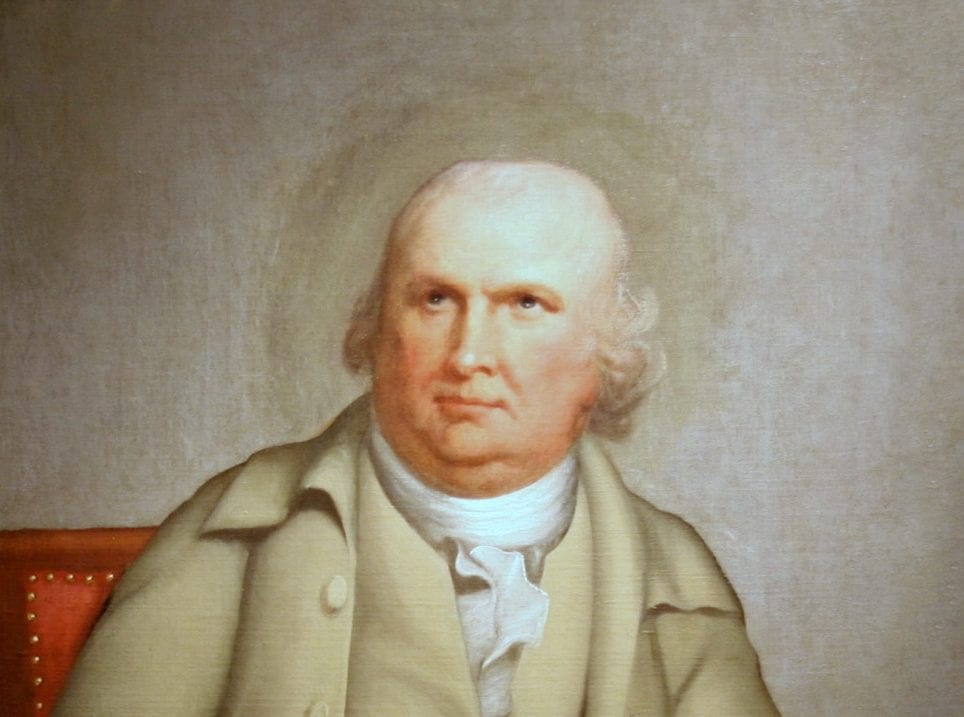

Second, while Thacher noted Cornwallis’s conspicuous absence from the ceremony, he failed to witness the subtle but symbolically important maneuvers of the ranking British, French, and American officers. Cornwallis’s second in command, Brigadier General Charles O’Hara (1740–1802), first attempted to surrender his sword to Rochambeau. Understanding this as an insult to an American army fighting for the recognition of its nation’s independence, Rochambeau pointed toward Washington. But the Continental commander-in-chief also refused O’Hara’s sword, directing instead that it be given to Major General Benjamin Lincoln (1733–1810), his own second in command. When Lincoln accepted O’Hara’s sword, young America reinforced its equality among nations on the world’s stage.

A third detail is more difficult to substantiate. As Redcoats threw down their weapons, the British military band reportedly played a tune called “The World Turned Upside Down.”

Source: James Thacher, A Military Journal during the American Revolutionary War, from 1775 to 1783…. (Boston: Richardson and Lord, 1823), 345–48. https://archive.org/details/militaryjournal00thac/page/344

This is to us a most glorious day, but to the English one of bitter chagrin and disappointment. Preparations are now making to receive as captives, that vindictive, haughty commander, and that victorious army, who by their robberies and murders have so long been a scourge to our brethren of the southern states. Being on horseback, I anticipate a full share of satisfaction in viewing the various movements in the interesting scene.

The stipulated terms of capitulation are similar to those granted to General Lincoln at Charleston the last year.[1] The captive troops are to march out with shouldered arms, colors cased, and drums beating a British or German march, and to ground their arms at a place assigned for the purpose. The officers are allowed their side arms and private property, and the generals and such officers as desire it, are to go on parole to England or New York. The marines and seamen of the king’s ships are prisoners of war to the navy of France, and the land forces to the United States. All military and artillery stores to be delivered up unimpaired. The royal prisoners to be sent into the interior of Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania in regiments, to have rations allowed them equal to the American soldiers, and to have their officers near them. Lord Cornwallis to man and dispatch the Bonetta sloop of war with dispatches to Sir Henry Clinton at New York without being searched, the vessel to be returned and the hands accounted for.

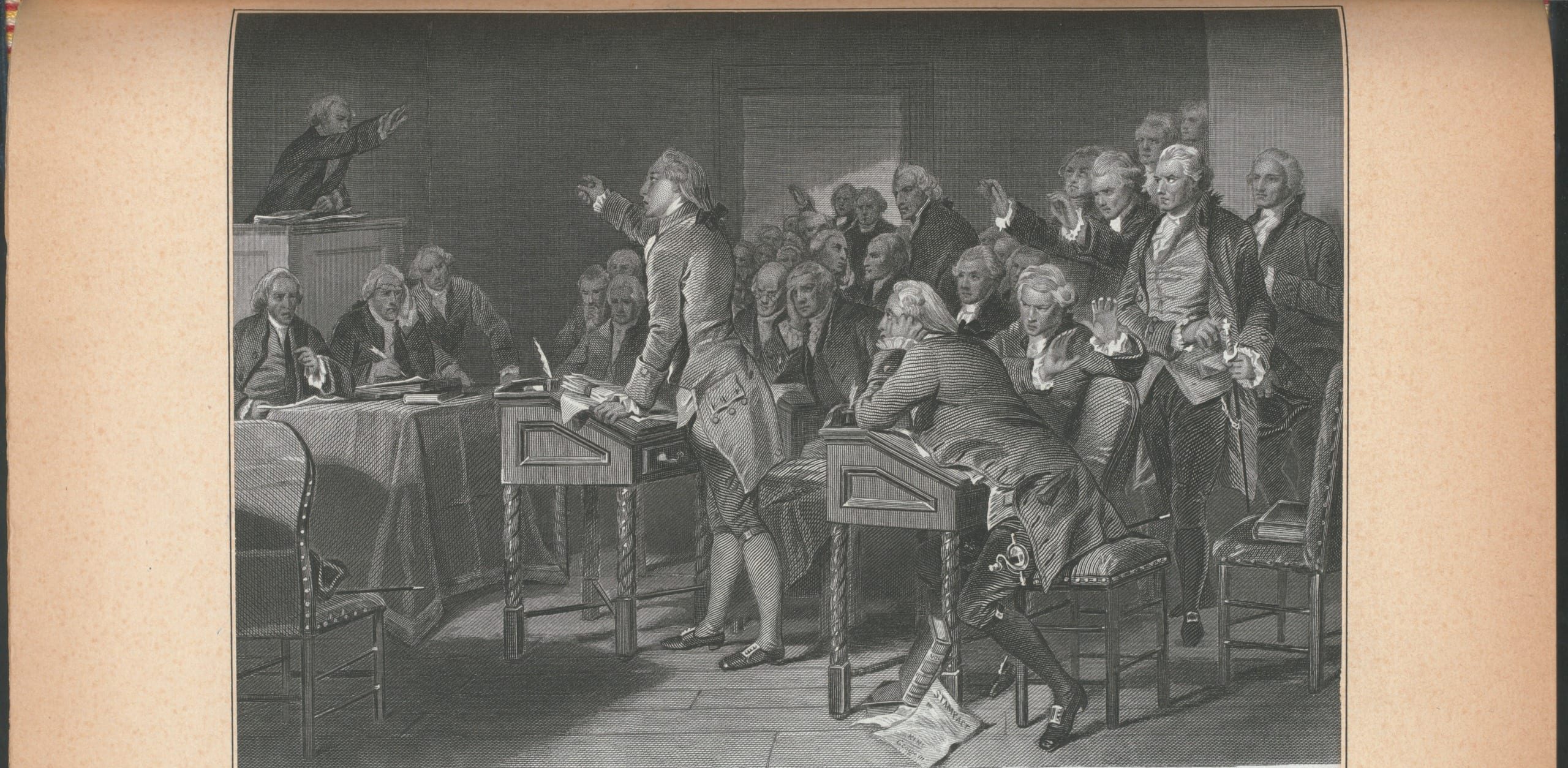

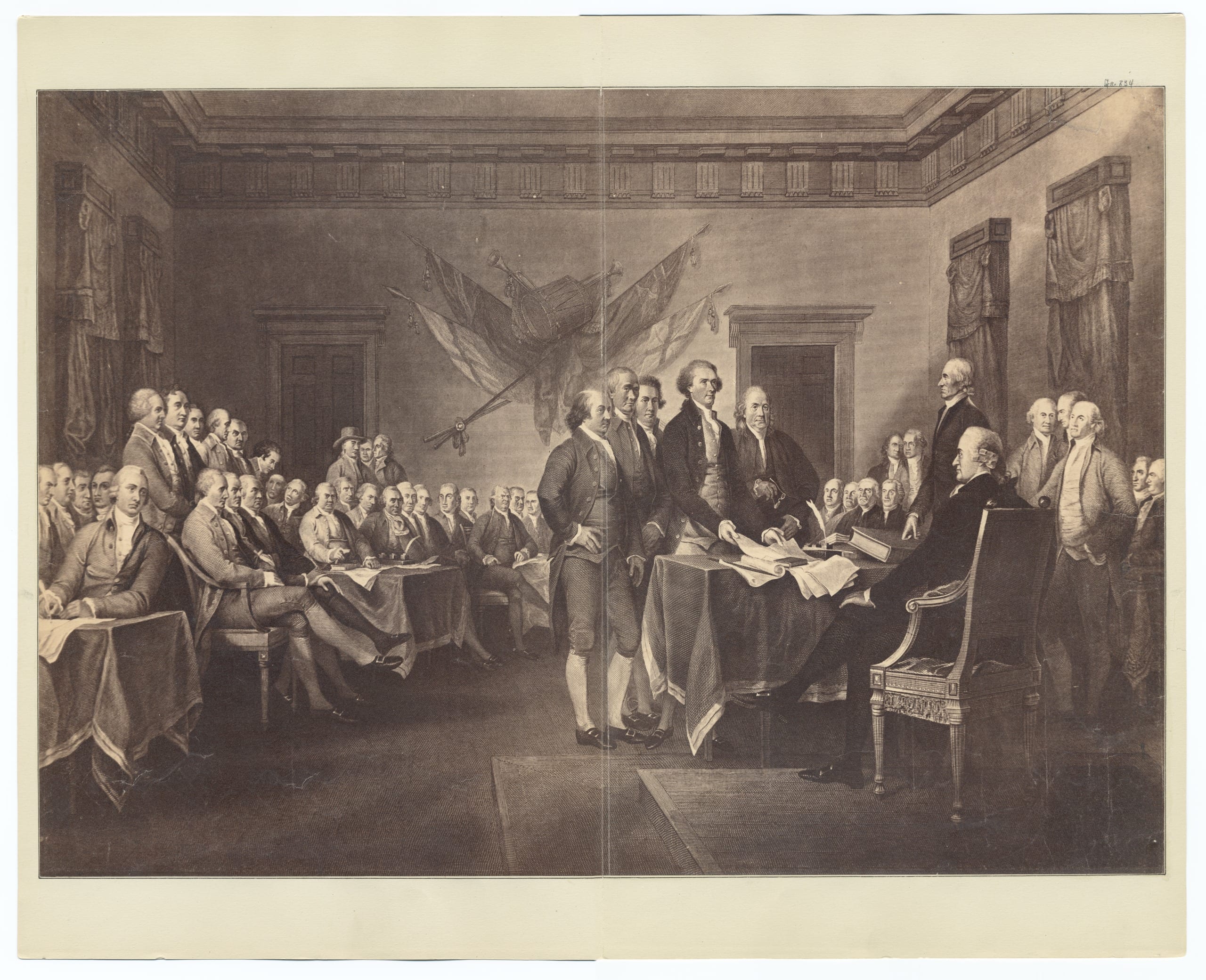

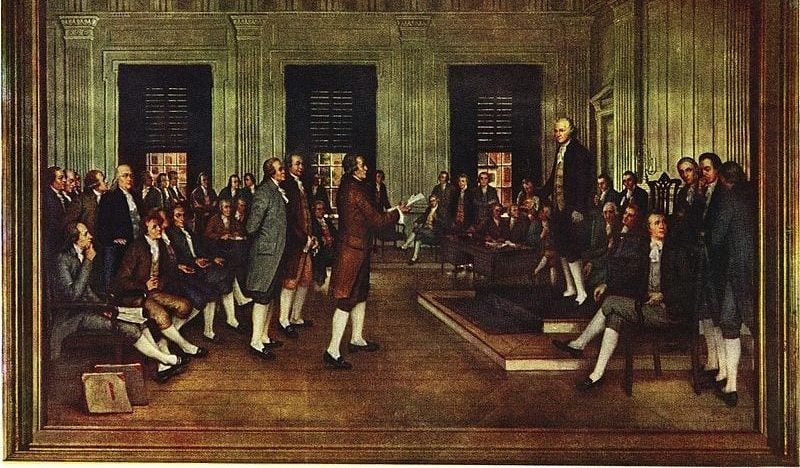

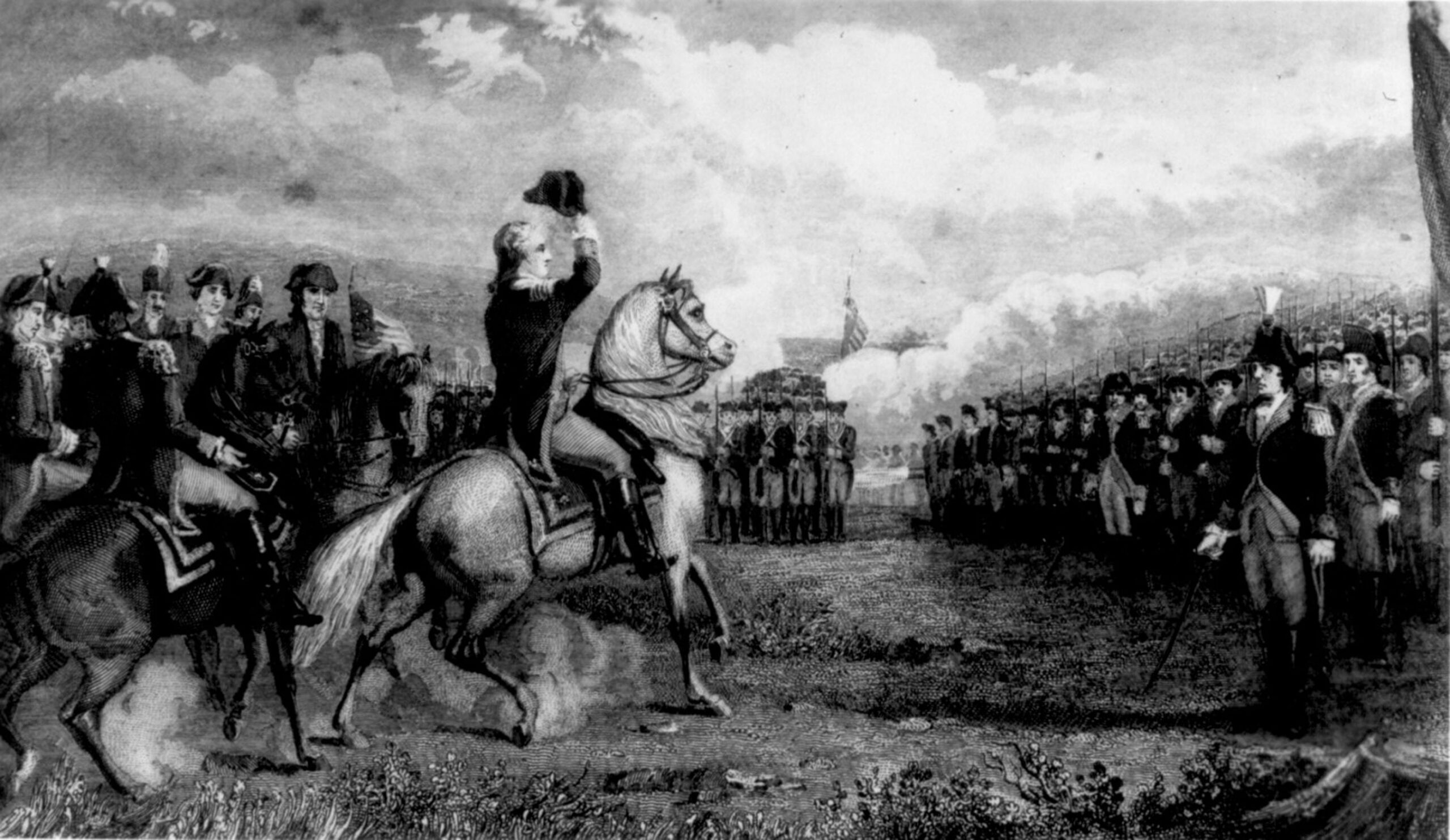

At about twelve o’clock, the combined army was arranged and drawn up in two lines extending more than a mile in length. The Americans were drawn up in a line on the right side of the road, and the French occupied the left. At the head of the former the great American commander, mounted on his noble courser,[2] took his station, attended by his aides. At the head of the latter was posted the excellent Count Rochambeau and his suite. The French troops, in complete uniform, displayed a martial and noble appearance, their band of music, of which the timbrel[3] formed a part, is a delightful novelty, and produced while marching to the ground a most enchanting effect. The Americans, though not all in uniform nor their dress so neat, yet exhibited an erect soldierly air, and every countenance beamed with satisfaction and joy. The concourse of spectators from the country was prodigious, in point of numbers probably equal to the military, but universal silence and order prevailed.

It was about two o’clock when the captive army advanced through the line formed for their reception. Every eye was prepared to gaze on Lord Cornwallis, the object of peculiar interest and solicitude; but he disappointed our anxious expectations; pretending indisposition, he made General O’Hara his substitute as the leader of his army. This officer was followed by the conquered troops in a slow and solemn step, with shouldered arms, colors cased, and drums beating a British march. Having arrived at the head of the line, General O’Hara, elegantly mounted, advanced to his excellency, the commander-in-chief, taking off his hat, and apologized for the non-appearance of Earl Cornwallis. With his usual dignity and politeness his excellency pointed to Major General Lincoln for directions, by whom the British army was conducted into a spacious field where it was intended they should ground their arms.

The royal troops, while marching through the line formed by the allied army, exhibited a decent and neat appearance, as respects arms and clothing, for their commander opened his store and directed every soldier to be furnished with a new suit complete, prior to the capitulation. But in their line of march we remarked a disorderly and un-soldierly conduct; their step was irregular and their ranks frequently broken.

But it was in the field when they came to the last act of the drama, that the spirit and pride of the British soldier was put to the severest test—here their mortification could not be concealed. Some of the platoon officers appeared to be exceedingly chagrined when giving the word “ground arms,” and I am a witness that they performed this duty in a very un-officer-like manner, and that many of the soldiers manifested a sullen temper, throwing their arms on the pile with violence, as if determined to render them useless. This irregularity, however, was checked by the authority of General Lincoln. After having grounded their arms and divested themselves of their accouterments, the captive troops were conducted back to Yorktown and guarded by our troops until they could be removed to the place of their destination.

The British troops that were stationed at Gloucester surrendered at the same time, and in the same manner to the command of the Duke de Lauzun.[4]

This must be a very interesting and gratifying transaction to General Lincoln, who having himself been obliged to surrender an army to a haughty foe the last year, has now assigned him the pleasing duty of giving laws to a conquered army in return, and of reflecting that the terms which were imposed on him are adopted as a basis of the surrender in the present instance. It is a very gratifying circumstance that every degree of harmony, confidence, and friendly intercourse subsisted between the American and French troops during the campaign, no contest except an emulous spirit to excel in exploits and enterprise against the common enemy, and a desire to be celebrated in the annals of history for an ardent love of great and heroic actions.

We are not to be surprised that the pride of the British officers is humbled on this occasion, as they have always entertained an exalted opinion of their own military prowess, and affected to view the Americans as a contemptible, undisciplined rabble. But there is no display of magnanimity when a great commander shrinks from the inevitable misfortunes of war, and when it is considered that Lord Cornwallis has frequently appeared in splendid triumph at the head of his army by which he is almost adored, we conceive it incumbent on him cheerfully to participate in their misfortunes and degradations, however humiliating; but it is said he gives himself up entirely to vexation and despair.

- 1. General Henry Clinton (1730–1795), British commander-in-chief for North America, had denied Major General Benjamin Lincoln the traditional honors of war when, on May 12, 1780, Lincoln surrendered after the Siege of Charleston. Allowing the defeated army to surrender with flags flying was seen as a gesture of respect and an acknowledgment of its valor.

- 2. A swift, strong horse—in this case, Washington’s horse, “Nelson” (1763–1790).

- 3. A tambourine or similar percussion instrument.

- 4. Armand Louis de Gontaut (1747–1793), Duc de Lauzun, was a brigadier general in the French army.

Cornwallis to Clinton

October 20, 1781

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.