No study questions

No related resources

My Lord,

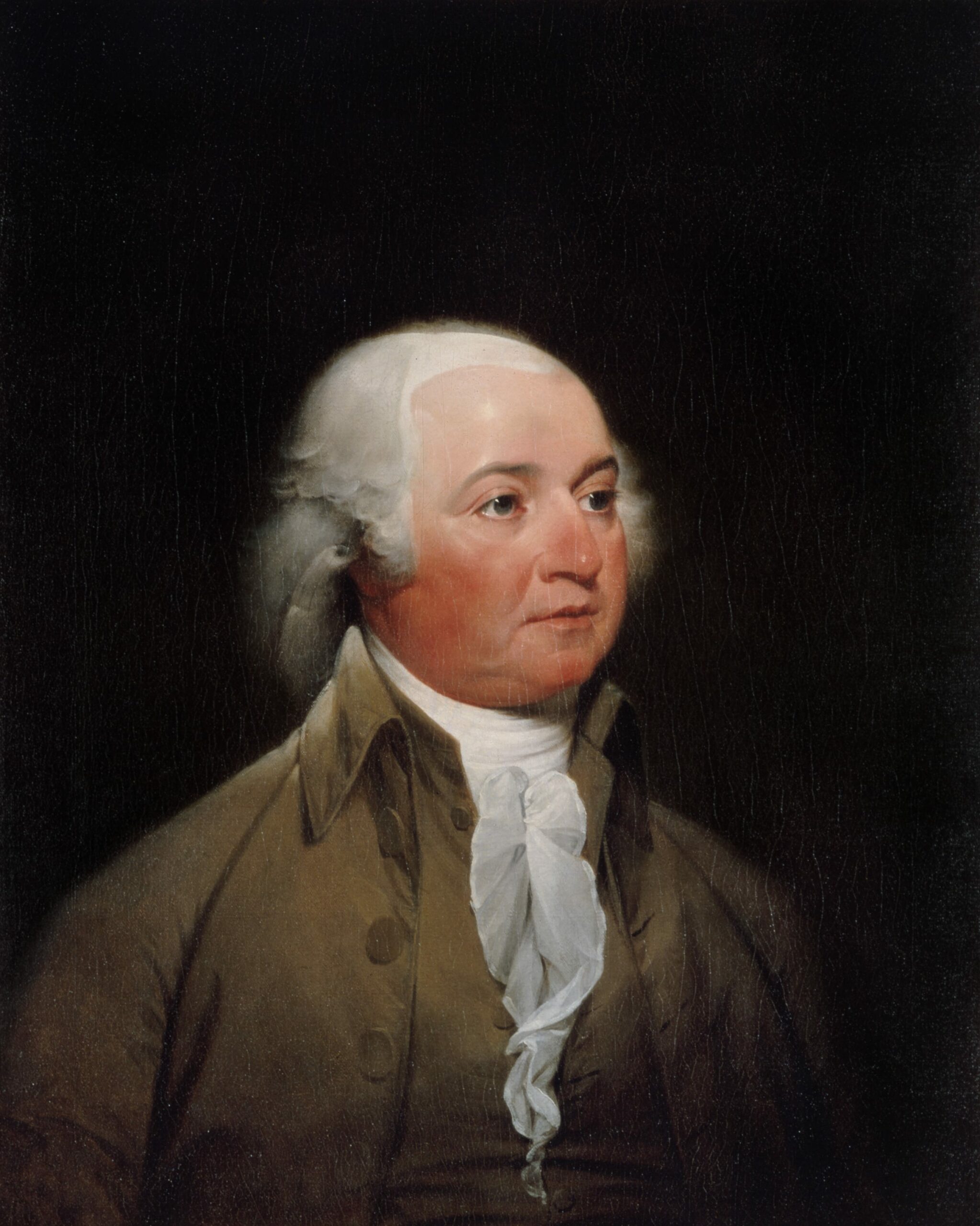

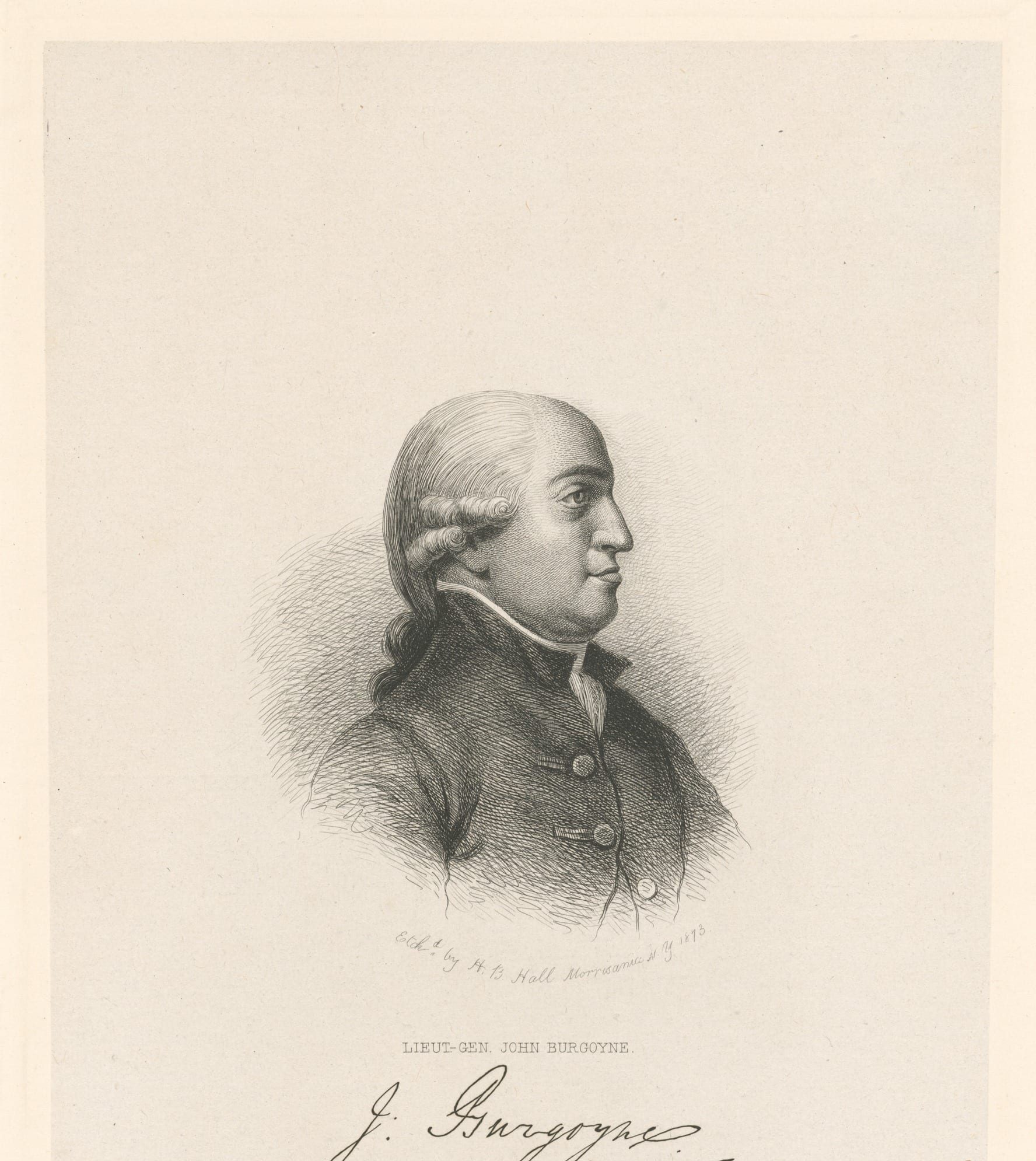

The last time I had the honor of being in your Lordship’s company, you observed that you were utterly at a loss to what facts many parts of the Declaration of Independence published by the Philadelphia Congress referred, and that you wished they had been more particularly mentioned, that you might better judge of the grievances, alledged as special causes of the separation of the Colonies from the other parts of the Empire. This hint from your Lordship induced me to attempt a few Strictures upon the Declaration. Upon my first reading it, I thought there would have been more policy in leaving the World altogether ignorant of the motives to this Rebellion, than in offering such false and frivolous reasons in support of it; and I flatter myself, that before I have finished this letter, your Lordship will be of the same mind. But I beg leave first to make a few remarks upon its rise and progress.

I have often heard men, (who I believe were free of any party influence) express their wishes, that the claims of the Colonies to an exemption from the authority of Parliament in imposing Taxes had been conceded; because they had no doubts that America would have submitted in all other cases; and so this unhappy Rebellion, which has already proved fatal to many hundreds of Subjects of the Empire, and probably will to many thousands more, might have been prevented.

The Acts for imposing Duties and Taxes may have accelerated the Rebellion, and if this could have been foreseen, perhaps, it might have been good policy to have omitted or deferred them; but I am of the opinion, that if no Taxes or Duties had been laid upon the Colonies, other pretences would have been found for exception to the authority of Parliament. The body of the people in the Colonies, I know, were easy and quiet. They felt no burdens. They were attached, indeed, in every Colony to their own particular Constitutions, but the Supremacy of Parliament over the whole gave them no concern. They had been happy under it for an hundred years past: They feared no imaginary evils for an hundred years to come. But there were men in each of the principal Colonies, who had Independence in view, before any of those Taxes were laid, or proposed, which have since been the ostensible cause of resisting the execution of the Acts of Parliament. Those men have conducted the Rebellion in the several stages of it, until they have removed the constitutional powers of Government in each Colony, and have assumed to themselves, with others, a supreme authority over the whole…

It does not, however, appear, that there was any regular plan formed for attaining to Independence, any further than that every fresh incident which could be made to serve the purpose, by alienating the affections of the Colonies from the kingdom, should be improved accordingly. One of these incidents happened in the year 1764. This was the act of Parliament for granting certain duties on goods in the British Colonies, for the support of Government, etc. At the same time a proposal was made in Parliament, to lay a stamp duty upon certain writings in the Colonies; but this was deferred until the next Session, that the agents of the Colonies might notify the several Assemblies in order to their proposing any way, to them more eligible, for raising a sum for the same purpose with that intended by a stamp duty. The Colony of Massachusetts was more affected by the Act for granting duties, than any other Colony. More molasses, the principal article from which any duty could arise, was distilled into spirits in that Colony than in all the rest. The Assembly of the Massachusetts, therefore, was the first that took any publick notice of the Act, and the first which ever took exception to the right of Parliament to impose Duties on Taxes on the Colonies, whilst they had no representatives in the House of Commons. This they did in a letter to their Agent in the summer of 1764, which they took care to print and publish before it was possible for him to receive it. And in this letter they recommend to him a pamphlet, wrote by one of their members, in which there are proposals for admitting representatives from the Colonies to sit in the House of Commons.

I have this special reason, my Lord, for taking notice of this Act of the Massachusetts’ Assembly; that though an American representation is thrown out as an expedient which might obviate the objections to Taxes upon the Colonies, yet it was only intended to amuse the authority in England; and as soon as it was known to have its advocates here, it was renounced by the Colonies, and even by the Assembly of the Colony which first proposed it, as utterly impracticable. In every stage of the Revolt, the same disposition has always appeared. No precise, unequivocal terms of submission to the authority of Parliament in any case, have even been offered by any Assembly. A concession has only produced further demand, and I verily believe if every thing had been granted short of absolute Independence, they would not have been contented; for this was the object from the beginning. One of the most noted among the American clergy, prophesied eight years ago, that within eight years from that time, the Colonies would be formed into three distinct independent Republics, Northern, Middle, and Southern. I could give your Lordship many irrefragable proofs of this determined design, but I reserve them for a future letter, the subject of which shall be the rise and progress of the Rebellion in each of the Colonies…

It will cause greater prolixity to analyze the various parts of this Declaration, than to recite the whole. I will, therefore, present it to your Lordship’s view in distinct paragraphs, with my remarks, in order as the paragraphs are published:

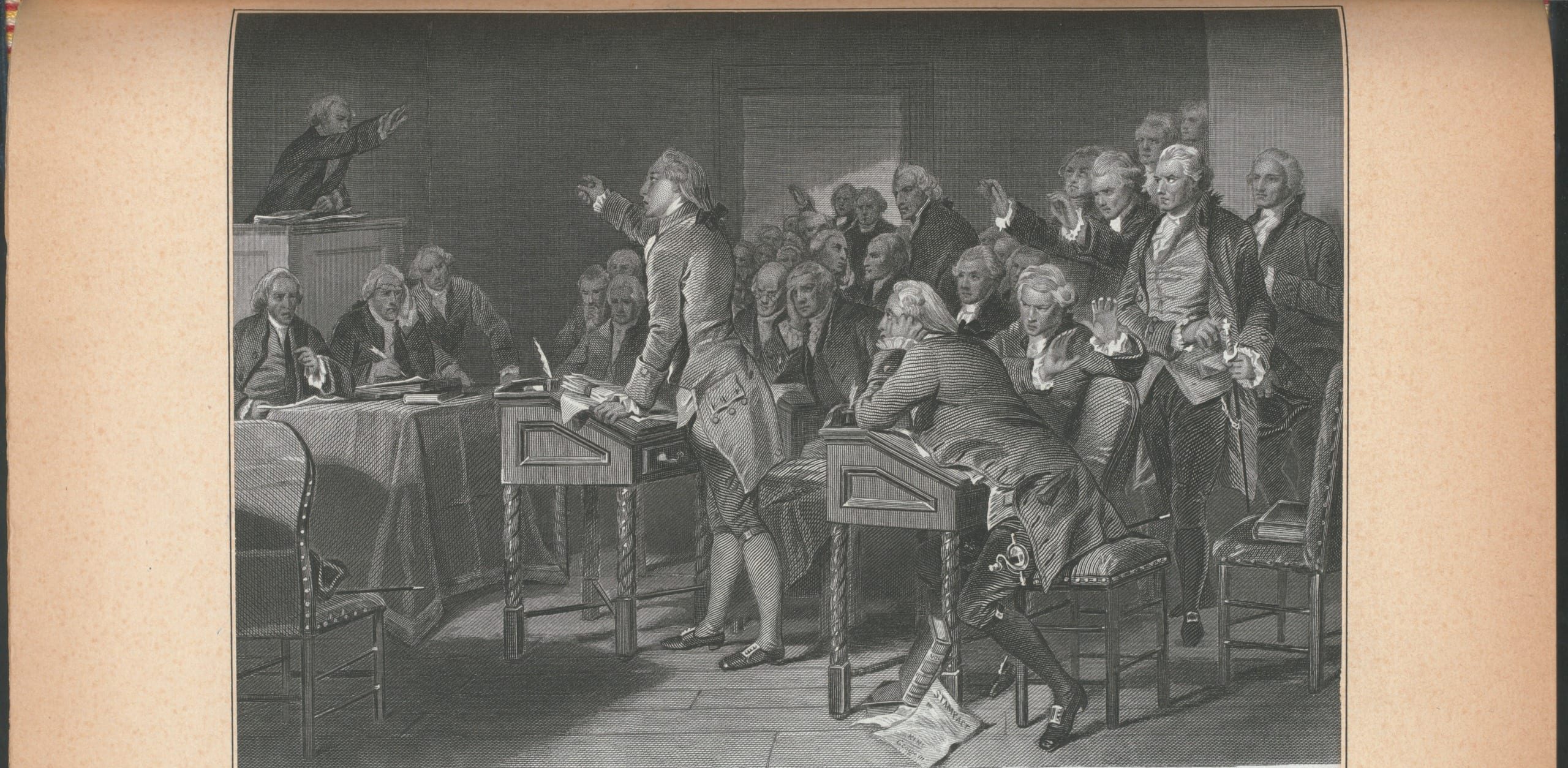

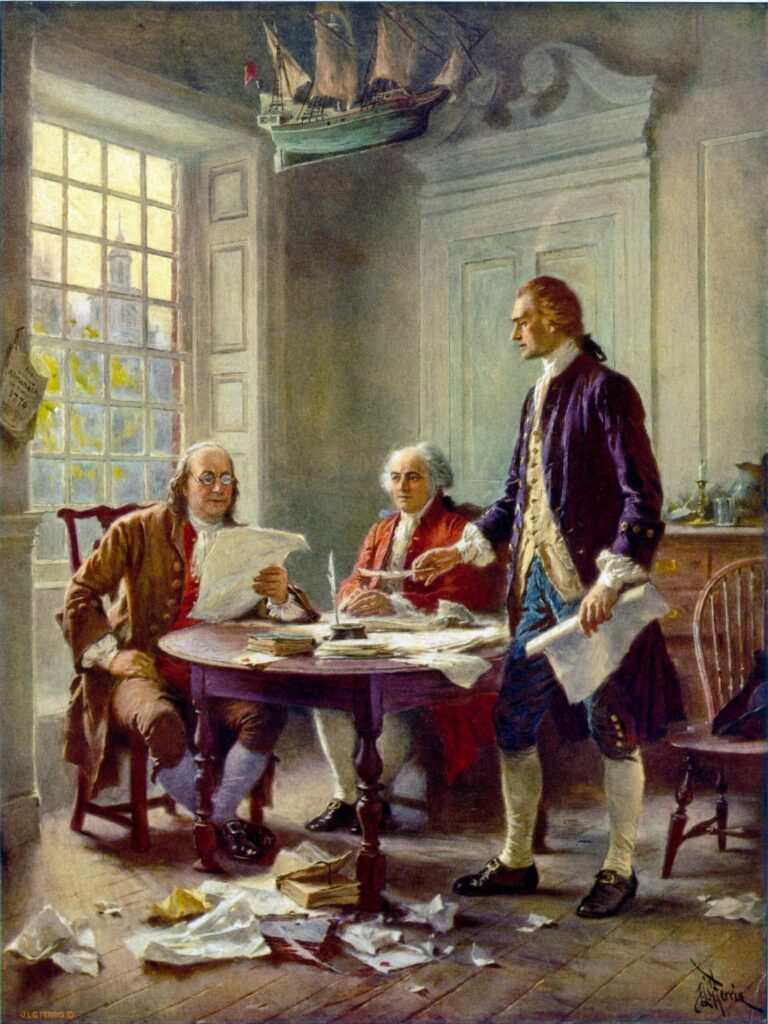

In Congress, July 4, 1776

A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America in General Congress assembled.

When in the course of human events it becomes necessary for One People to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the Powers of the Earth, the separate and equal station to which the laws of nature and of nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation…

They begin, my Lord, with a false hypothesis. That the Colonies are one distinct people, and the kingdom another, connected by political bands. The Colonies, politically considered, never were a distinct people from the kingdom. There never has been but one political band, and that was just the same before the first Colonists emigrated as it has been ever since, the Supreme Legislative Authority, which hath essential rights, and is indispensably bound to keep all parts of the Empire entire, until there may be a separation consistent with the general good of the Empire, of which good, from the nature of government, this authority must be the sole judge…

The first order, He has refused his assent to laws the most wholesome and necessary for the public good; is of so general a nature, that it is not possible to conjecture to what laws or to what Colonies it refers. I remember no laws which any Colony has been restrained from from passing, so as to cause any complaint of grievance, except those for issuing a fraudulent paper-currency, and making it a legal tender; but this is a restraint which for many years past has been laid on Assemblies by an act of Parliament, since which such laws cannot have been offered to the King for his allowance. I therefore believe this to be a general charge, without any particulars to support it; fit enough to be placed at the head of a list if imaginary grievances.

The laws of England are or ought to be the laws of its Colonies. To prevent a deviation further than the local circumstances of any Colony may make necessary, all Colony laws are to be laid before the King; and if disallowed, they then become of no force. Rhode-Island, and Connecticut, claim by Charters, an exemption from this rule, and as their laws are never presented to the King, they are out of the question. Now if the King is to approve of all laws, or which is the same thing, of all which the people judge for the public good, for we are to presume they pass no other, this reserve in all Charters and Commissions is futile. This charge is still more inexcusable, because I am well informed, this disallowance of Colony laws has been much more frequent in preceding reigns, than in the present.

He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their public records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures.

To the same Colony [Massachusetts Bay] this also has respect; Your Lordship must remember the riotous, violent opposition to Government in the Town of Boston, which alarmed the whole Kingdom, in the year 1768. Four regiments of the King’s forces were ordered to that Town, to be aiding to the Civil Magistrate in restoring and preserving peace and order. The House of Representatives, which was then sitting in the Town, remonstrated to the Governor against posting Troops there, as being an invasion of their rights. He thought proper to adjourn them to Cambridge, where the House had frequently sat at their over desire, when they had been alarmed with fear of the small pox in Boston; the place therefore was not unusual. The public rooms of the College, were convenient for the Assembly to sit in, and the private houses of the Inhabitants for the Members to lodge in; it therefore was not uncomfortable. It was within four miles of the Town of Boston, and less distant than any other Town fit for the purpose.

When this step, taken by Governor, was known in England, it was approved, and conditional instructions were given to continue the Assembly at Cambridge. The House of Representatives raised the most frivolous objections against the authority of the Governor to remove the Assembly from Boston, but proceeded, nevertheless, to the business of the Session as they used to do. In the next Session, without any new cause, the Assembly refused to do any business unless removed to Boston. This was making themselves judges of the place, and by the same reason, of the time of holding the Assembly, instead of the Governor, who thereupon was instructed not to remove them to Boston, so long as they continued to deny his authority to carry them at any other place.

They fatigued the Governor by adjourning from day to day, refusing to do business one Session after another, while he gave his constant attendance to no purpose; and this they make the King’s fatiguing them to compel them comply with his measures.

A brief narrative of this unimportant dispute between an American Governor and his Assembly, needs as apology to your Lordship; how ridiculous then do those men make themselves, who offer it to the world as a ground to justify Rebellion?

He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly for opposing with manly firmness his Invasions on the Rights of the People.

Contentions between Governors and their Assemblies have caused dissolutions of such Assemblies, I suppose, in all the Colonies; in former as well as later times. I recollect but one instance of the dissolution of an Assembly by special order from the King, and that was in Massachusetts Bay. In 1768, the House of Representatives passed a vote or resolve, in prosecution of the plan of Independence incompatible with the subordination of the Colonies to the supreme authority of the Empire; and directed their Speaker to send a copy of it in circular letters to the Assemblies of the other Colonies, inviting them to avow the principles of the resolve, and to join in supporing them. No Government can long subsist, which admits of combinations of the subordinate powers against the supreme. This proceeding was therefore, justly deemed highly unwarrantable; and indeed it was the beginning of that unlawful confederacy, which has gone on until it has caused at least a temporary Revolt of all the Colonies which joined in it.

The Governor was instructed to require the House of Representatives, in their next Session to rescind or disavow this resolve, and it they refused, to dissolve them, as the only way to prevent their prosecuting the plan of Rebellion. They delayed a definitive answer, and he indulged them, until they had finished all the business of the Province, and then appeared this manly firmness in a rude answer and a peremptory refusal to comply with the King’s command. Thus, my Lord, the regular use of the prerogative in suppressing a begun Revolt, is urged as a a grievance to justify the Revolt.

He has refused for a long time after such dissolutions to cause others to be erected whereby the legislative powers, incapable of annihilation, have returned to the people at large for their exercise; the state remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasions from without and convulsions within.

This is connected with the last preceding article, and must relate to the same Colony only; for no other ever presumed, until the year 1774, when the general dissolution of the established government in all the Colonies was taking place, to convene an Assembly, without the Governor, by the meer act of the People.

In less than three months, after the Governor had dissolved the Assembly of Massachusetts Bay, the town of Boston, the first mover in all affairs of this nature, applied to him to call another Assembly. The Governor though he was the judge of the proper time for calling an Assembly, and refused. The town, without delay, chose their former members, whom they called a Committee, instead of Representatives; and they sent circular letters to all the other towns in the Province inviting them to choose Committees also; and all these Committees met in what they called a Convention, and chose the Speaker of the last house their Chairman. Here was a House of Representatives in every thing but name; and they were proceeding upon the business in the town of Boston, but were interrupted by the arrival of two or three regiments, and a spirited message from the Governor, and in two or three days returned to their homes.

This vacation of three months was the long time the people waited before they exercised their unalienable powers; the Invasions from without were the arrival or expectation of three or four regiments sent by the King to aid the Civil Magistrate in preserving the peace; and the Convulsions within were the tumults, riots and acts of violence which this Convention was called, not to suppress but to encourage…

He has kept among us, in times of peace, standing armies, without the consent of our legislatures.

This is too nurgatory to deserve any remark. He has kept no armies among them without the consent of the Supreme Legislature. It is begging the question to suppose that this authority was not sufficient without the aid of their own Legislatures.

He has affected to render the Military independent of, and superior to, the Civil Power.

When the subordinate Civil Powers of the Empire became Aiders of the people in acts of Rebellion, the King, as well he might, has employed the Military Power to reduce those rebellious Civil Powers to their constitutional subjection to the Supreme Civil Power. In no other sense has he ever affected to render the Military independent of, and superior to, the Civil Power.

He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our Constitution and unacknowledged by our Laws; giving his assent to their pretended Acts of Legislation.

This is a strange way of defining the part which the Kings of England take in conjunction with the Lords and Commons in passing Acts of Parliament. But why is our present Sovereign to be distinguished from all his predecessors since Charles the Second? Even the Republic which they affect to copy after, and Oliver, their favorite, because an Usurper, combined against them also. And then, how can a jurisdiction submitted to for more than a century be foreign to their constitution? And is it not the grossest prevarication to say this jurisdiction is unacknowledged by their laws, when all Acts of Parliament which respect them, have at all times been their rule of law in all their judicial proceedings? If this is not enough: their own subordinate legislatures have repeatedly in addresses, and resolves, in the most express terms acknowledged the supremacy of Parliament; and so late as 1764, before the conductors of this Rebellion had settled their plan, the House of Representatives of the leading Colony made a public declaration in an address to their Governor, that, although they humbly apprehended they might propose their objections, to the late Act of Parliament for granting certain duties in the British Colonies and Plantations in America, yet they at the same time acknowledged that it was their duty to yield obedience to it while it continued unrepealed.

If the jurisdiction of Parliament is foreign to their Constitution, what need of specifying instances, in which they have been subjected to it? Every Act must be an usurpation and injury. They must then be mentioned, my Lord, to shew, hypothetically, that even if Parliament had jurisdiction, such Acts would be a partial and injurious use of it. I will consider them, to know whether they are so or not.

For quartering large bodies of armed troops among us.

When troops were employed in America, in the last reign, to protect the Colonies against French invasion, it was necessary to provide against mutiny and desertion, and to secure proper quarters. Temporary Acts of Parliament were passed for that purpose, and submitted to the Colonies. Upon the peace, raised ideas took place in the Colonies, of their own importance, and caused a reluctance against Parliamentary authority, and an opposition to the Acts for quartering troops, not because the provision made was in itself unjust or unequal, but because they were Acts of a Parliament whose authority was denied. The provision was as similar to that in England as the state of the Colonies would admit…

For protecting them by a mock trial from punishment, for any murder which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States.

It is beyond human wisdom to form a system of laws so perfect as to be adapted to all cases. It is happy for a state, that there can be an interposition of legislative power in those cases, where an adherence to established rules would cause injustice. To try men before a biased and pre-determined Jury would be a mock trial. To prevent this, the Act of Parliament, complained of, was passed. Surely, if in any case Parliament may interpose and alter the general rule of law, it may in this. America has not been distinguished from other parts of the Empire. Indeed the removal of trials for the sake of unprejudiced and disinterested Juries, is altogether consistent with the spirit of out laws, and the practice of courts in changing the venue from one country to another.

For cutting off our trade with all parts of the world.

Certainly, my Lord, this could not be a cause of Revolt. The Colonies had revolted from the Supreme Authority, to which, by their constitutions, they were subject, before the Act was passed. A Congress had assumed an authority over the whole, and had rebelliously prohibited all commerce with the rest of the Empire. This act, therefore, will be considered by the candid world, as a proof of the reluctance in government against what is the dernier resort in every state, and as a milder measure to bring the Colonies to a re-union with all the rest of the Empire.

For imposing taxes on us without our consent.

How often has your Lordship heard it said, that the Americans are willing to submit to the authority of Parliament in all cases except that of taxes? Here we have a declaration made to the world of the causes which have impelled to a separation. We are to presume that it contains all which they that publish it are able to say in support of a separation, and that if any one cause was distinguished from another, special notice would be taken of it. That of taxes seems to have been in danger of being forgot. It comes in late, and in as slight a manner as is possible. And, I know, my Lord, that these men, in the early days of their opposition to Parliament, have acknowledged that they pitched upon this subject of taxes, because it was most alarming to the people, every man perceiving immediately that he is personally affected by it; and it has, therefore, in all communities, always been a subject more dangerous to government than any other, to make innovation in; but as their friends in England had fell in with the idea that Parliament could have no right to tax them because not represented, they thought it best it should be believed they were willing to submit to other acts of legislation until this point of taxes could be gained; owning at the same time, that they could find no fundamentals in the English Constitution which made representation more necessary in acts for taxes, than acts for any other purpose; and that the world must have a mean opinion of their understanding, if they should rebel rather than pay a duty of three-pence per pound on tea, and yet be content to submit to an act which restrained them from making a nail to shoe their own horses. Some of them, my Lord, imagine they are as well acquainted with the nature of government, and with the constitution and history of England, as many of their partisans in the kingdom; and they will sometimes laugh at the doctrine of fundamentals from which even Parliament itself can never deviate; and they say it has been often held and denied merely to serve the cause of party; and that it must be so until these unalterable fundamentals shall be ascertained; that the great Patriots in the reign of King Charles the Second, Lord Russell, Hampden, Maynard, etc. whose memories they reverence, declared their opinions, that there were no bounds to the power of Parliament by any fundamentals whatever, and that even the hereditary succession to the Crown might be, as it since has been, altered by the Act of Parliament; whereas they who call themselves Patriots in the present day held it to be a fundamental, that there can be no taxation without representation, and that Parliament cannot alter it.

But as this doctrine was held by their friends, and was of service to their cause until they were prepared for a total Independence, they appeared to approve it: As they have now no further occasion for it, they take no more notice of an act for imposing taxes than of many other acts; for a distinction in the authority of Parliament in any particular case cannot serve their claim to a general exemption, which they are now preparing to assert…

He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his protection and waging War against us.

He has plundered our Seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our Towns, and destroyed the Lives of our People.

He is at this time, transporting large Armies of foreign mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation an tyranny, already begun with circumstances of cruelty and perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the head of a civilized Nation.

He has constrained our Fellow Citizens, taken captive on the high Seas, to bear arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their Friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their hands.

He has excited domestik insurrections amongst us and has endeavored to bring on the Inhabitants of our frontiers the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

These, my Lord, would be weighty charges from a loyal and dutiful people against an unprovoked Sovereign: They are more than the people of England pretended to bring against King James the Second, in order to justify the Revolution. Never was there an instance of more consummate effrontery. The Acts of a justly incensed Sovereign for suppressing a most unnatural, unprovoked Rebellion, are here assigned as the causes of this Rebellion. It is immaterial whether they are true or false. They are all short of the penalty of the laws which had been violated. Before the date of nay one of them, the Colonists has as effectually renounced their allegiance by their deeds as they have since done by their words. They had displaced the civil and military officers appointed by the King’s authority and set up others in the stead. They had new modeled their civil governments, and appointed a general government, independent of the King, over the whole. They had taken up arms, and made a public declaration of their resolution to defend themselves, against the forces employed to support his legal authority over them. To subjects, who had forfeited their lives by acts of Rebellion, every act of the Sovereign against them, which falls short of the forfeiture, is an act of favour. A most ungrateful return has been made for this favour. It has been improved to strengthen and confirm the Rebellion against him…

A Prince, whose character is thus marked, by every act which defines the tyrant. is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

Indignant resentment must seize the breast of every loyal subject. A tyrant, in modern language, means, not merely an absolute and arbitrary, but a cruel, merciless Sovereign. Have these men given an instance of any one Act in which the King has exceeded the just Powers of the Crown as limited by the English Constitution? Has he ever departed from known established laws, and substituted his own will as the rule of his actions? Has there ever been a Prince by whom subjects in rebellion, have been treated with less severity, or with longer forbearance?…

Gratitude, I am sensible, is seldom to be found in a community, but so sudden a revolt from the rest of the Empire, which had incurred so immense a debt, and with which it remains burdened, for the protection and defence of the Colonies, and at their most importunate request, is an instance of ingratitude no where to be paralleled.

Suffer me, my Lord, before I close this letter, to observe that though the professed reason for publishing the Declaration was a decent respect to the opinions of mankind, yet the real design was to reconcile the people of America to that Independence, which always before, they had been made to believe was not intended. This design has too well succeeded. The people have not observed the fallacy in reasoning from the whole to part; nor the absurdity of making the governed to be governors. From a disposition to receive willingly complaints against Rulers, facts misrepresented have passed without examining. Discerning men have concealed their sentiments, because under the present free government in America, no man yet, by writing or speaking, contradict any part of this Declaration, without being deemed an enemy to his country, and exposed to the rage and fury of the populace.

London, October 15th, 1776

Excerpts from Founding Documents

December 31, 1776

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.