Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

No related resources

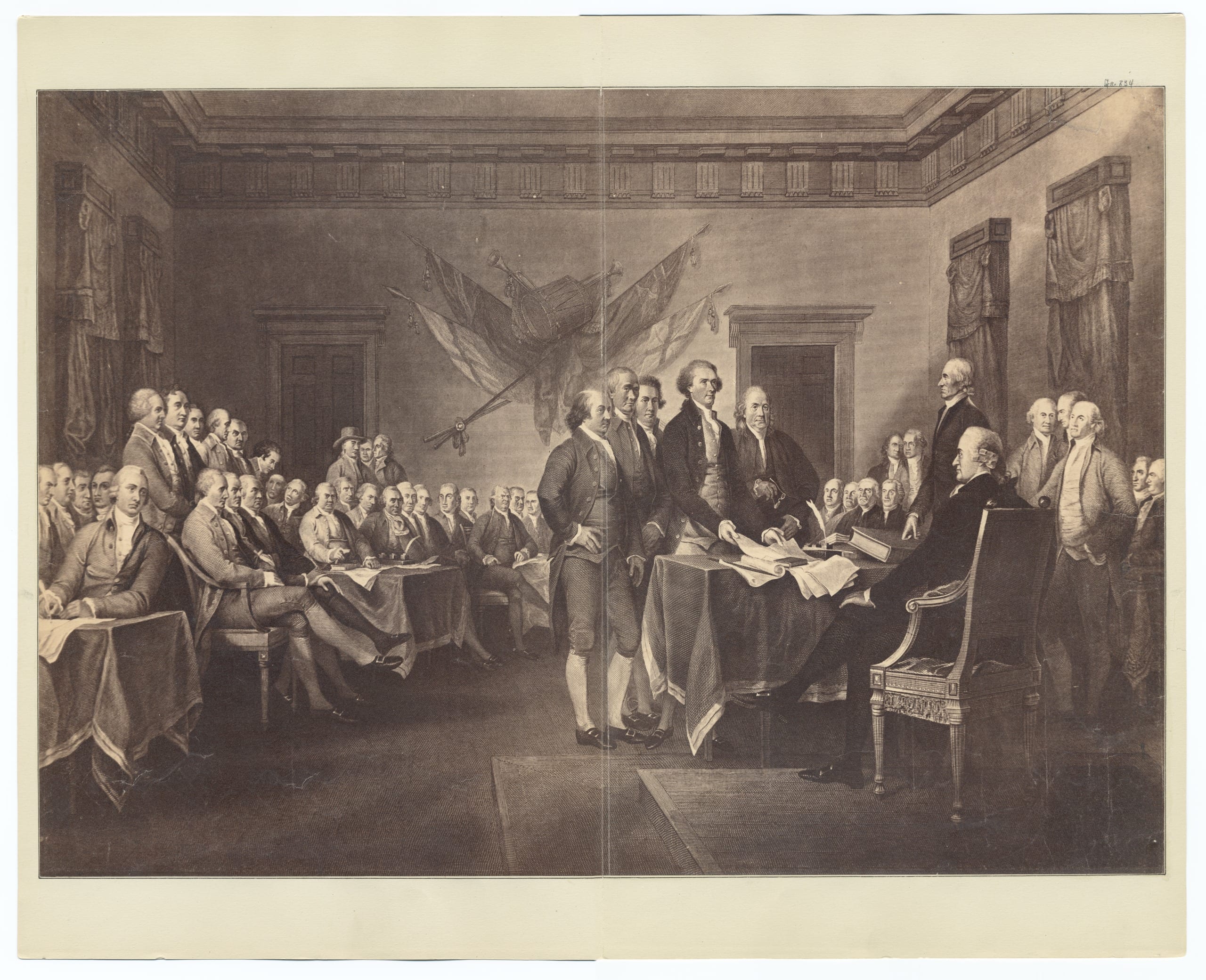

News of the Continental Congress’s July 2 approval of Richard Henry Lee’s resolution to separate from Great Britain—together with its July 4 passage of the Declaration of Independence—traveled by sail and on horseback. As a result, it took about two weeks for people in and around Boston to learn that the crisis within the British empire had been transformed (at least in the eyes of American Patriots) into a war between Great Britain and the sovereign United States. This newspaper account of their reactions highlights events organized by elected officials to celebrate independence as well as more spontaneous displays of the people’s support for Congress’s decisions.

WATERTOWN, JULY 22….

Thursday last,[1] pursuant to the orders of the honorable council, was proclaimed, from the balcony of the State House in Boston, the DECLARATION of the AMERICAN CONGRESS, absolving the United Colonies from their allegiance to the British crown, and declaring them FREE and INDEPENDENT STATES. There were present on the occasion, in the council chamber, the committee of council, a number of the honorable House of Representatives, the magistrates, ministers, selectmen, and other gentlemen of Boston and the neighboring towns; also the committee of officers of the Continental regiments stationed in Boston, and other officers. Two of those regiments were under arms in King Street, formed into three lines on the north side of the street, and in thirteen divisions; and a detachment from the Massachusetts Regiment of Artillery, with two pieces of cannon, was on their right wing. At one o’clock the Declaration was proclaimed by the sheriff of the county of Suffolk,[2] which was received with great joy expressed by three huzzahs from the concourse of people assembled on the occasion. After which, on a signal given, thirteen pieces of cannon were fired at the fort on Fort Hill, the forts at Dorchester Neck, the Castle, the Nantasket, and Point Alderton, likewise discharged their cannon. Then the detachment of artillery fired their cannon thirteen times, which was followed by the two regiments giving their fire from the thirteen divisions in succession. These firings corresponded to the number of the American states united. The ceremony was closed with a proper collation[3] to the gentlemen in the council chamber; during which the following toasts were given by the president of the council,[4] and heartily pledged by the company:

The bells of the town were rung on the occasion; and undissembled[5] festivity cheered and brightened every face.

On the same day a number of the members of the council (who were prevented attending the ceremony at Boston, on account of the small pox being there), together with those of the hon[orable] House of Representatives who were in town, and a number of other gentlemen, assembled at the council chamber in this town, where the said Declaration was also proclaimed by the secretary, from one of the windows; after which, the gentlemen present partook of a decent collation prepared on the occasion, and drank a number of constitutional toasts, and then retired.

We hear that on Thursday last every king’s arms[6] in Boston, and every sign with any resemblance of it, whether lion and crown, pestle and mortar and crown, heart and crown, etc., together with every sign that belonged to a Tory was taken down, and made a general conflagration of in King Street.

The king’s arms, in this town, was on Saturday last,[7] also defaced.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.