Next Document

Plan of Union

September 28, 1774

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

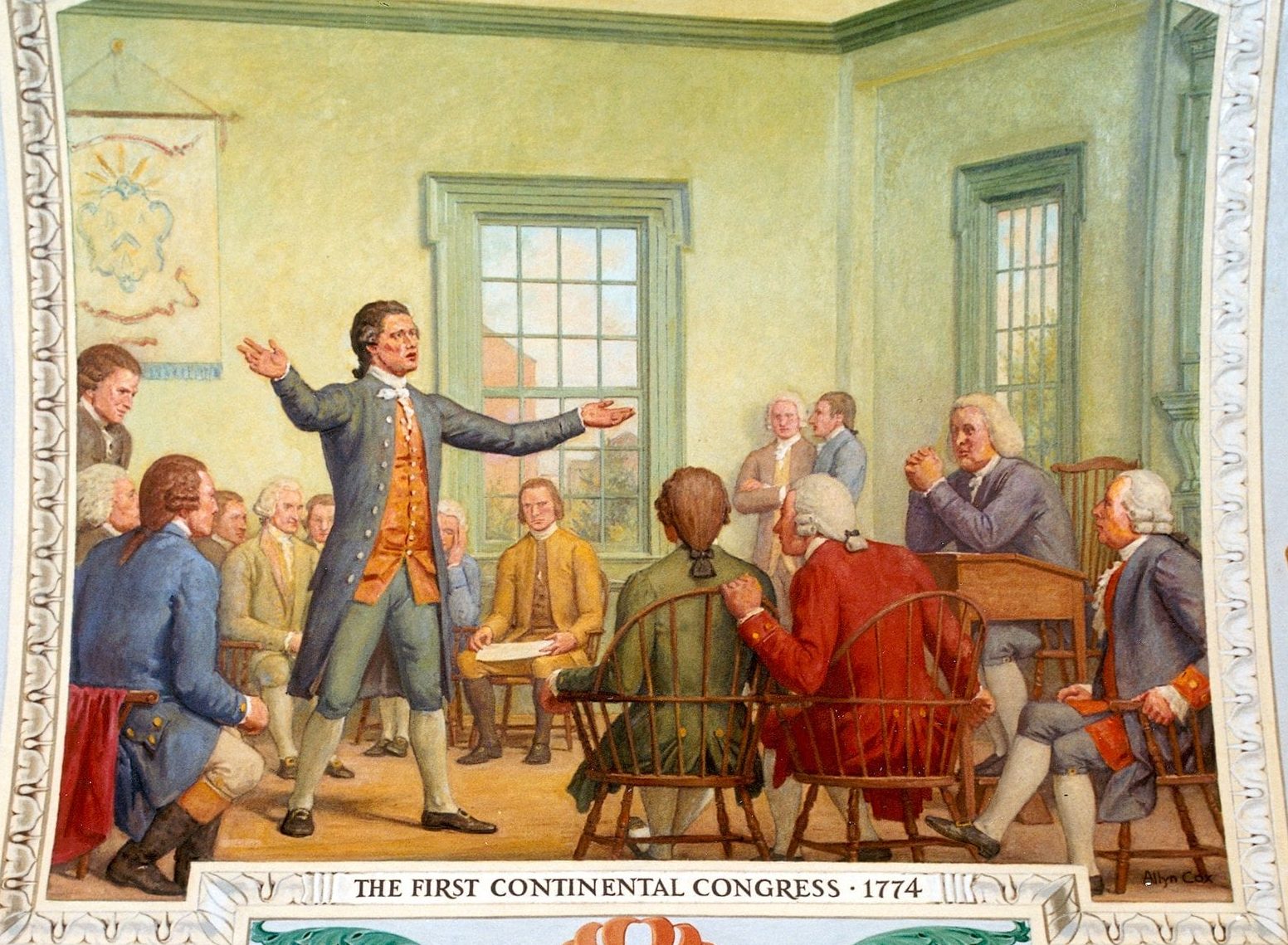

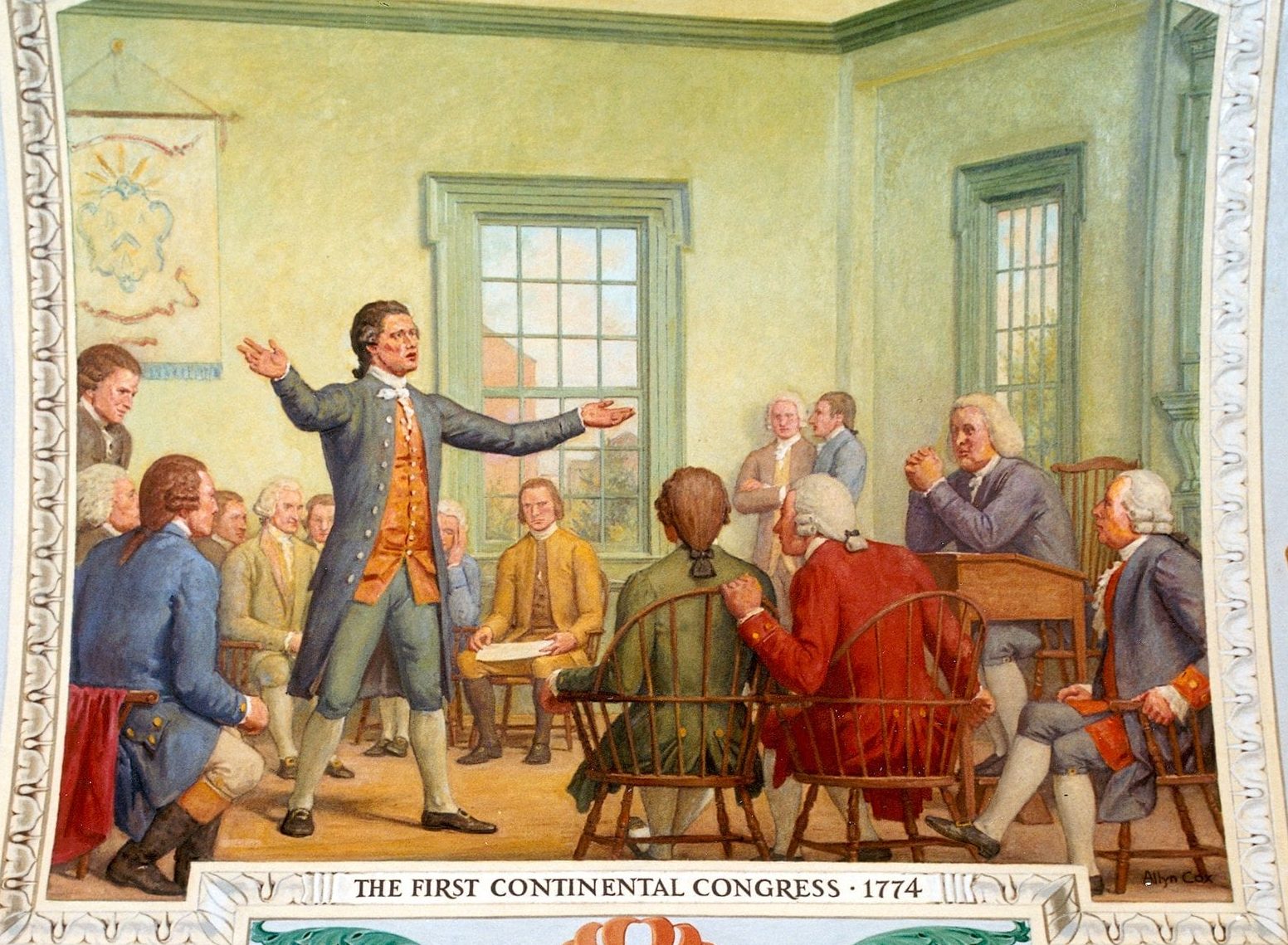

One manifestation of Americans’ outrage over the Coercive Acts was the convening in Philadelphia of the First Continental Congress, which met from September 5 to October 26, 1774. Although the Coercive Acts were aimed primarily at Massachusetts (which the hardline administration [1770–1782] of Lord North [1732–1792] sought to punish for the Boston Tea Party), colonists throughout America understood that if these laws could deny basic English liberties there, then these rights could be denied anywhere. As a result, the delegates to Congress came from everywhere except Georgia, which needed the help of the British army to fight Creek Indians on its frontier. Virginia’s delegation included Patrick Henry (1736–1799) and George Washington (1732–1799). New York’s included John Jay (1745–1829). Samuel Adams (1722–1803) and his second cousin John Adams (1735–1826) sat among the representatives of Massachusetts. In total, fifty-six men from twelve colonies gathered to debate and decide what to do next.

Philadelphians extended an enthusiastic welcome with a celebration on September 16. This account of the festivities, which took place in the City Tavern and the Pennsylvania State House (later known as Independence Hall), makes clear that, although united against the Coercive Acts, it might not be easy for Congress to help bring about the “happy reconciliation between Great Britain and her colonies” to which they raised their wine glasses. Just about every sympathetic British politician was a Whig—and Lord North, a Tory, enjoyed widespread support within Parliament.

On Friday last[1] the honorable delegates, now met in General Congress, were elegantly entertained by the gentlemen of this city. Having met at the City Tavern about 3 o’clock, they were conducted from thence to the State House by the managers of the entertainment, where they were received by a very large company composed of the clergy, such genteel strangers as happened to be in town, and a number of respectable citizens, making in the whole near 500. After dinner the following toasts were drank, accompanied by music and a discharge of cannon.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.