Introduction

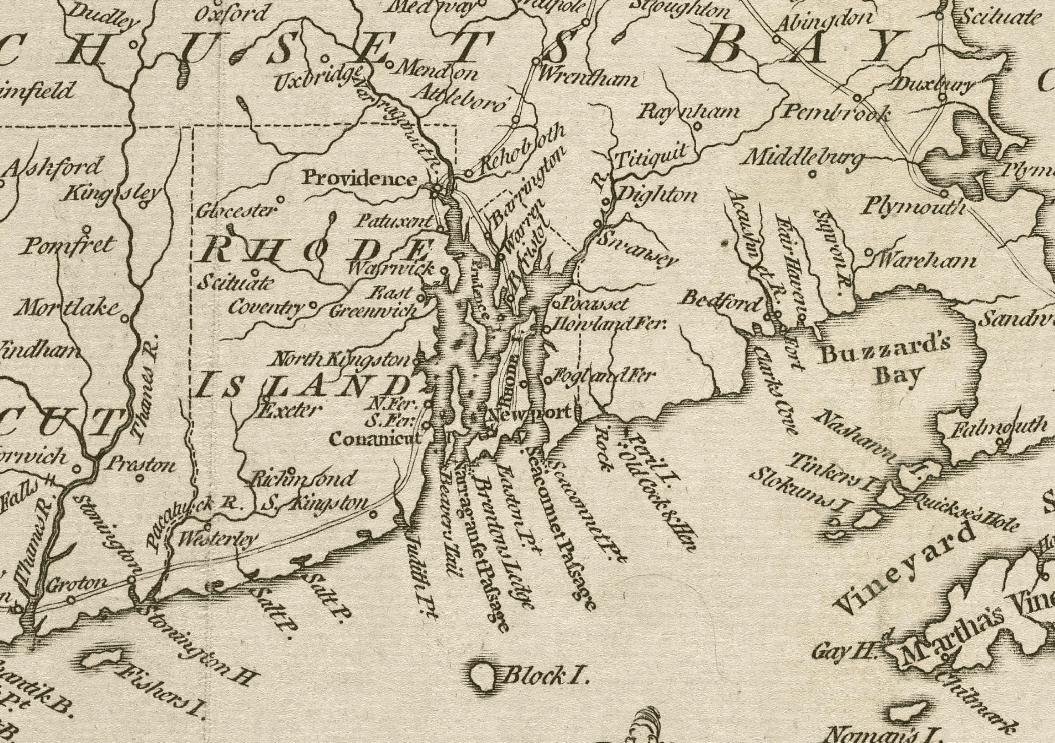

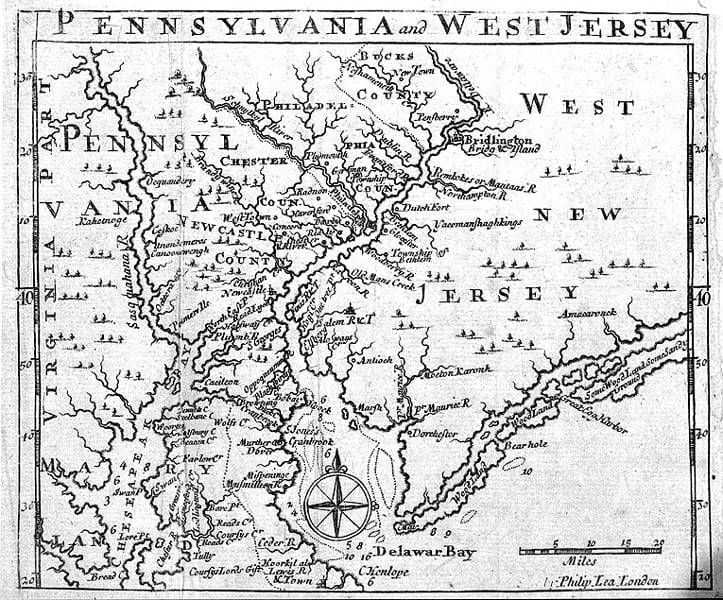

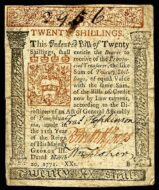

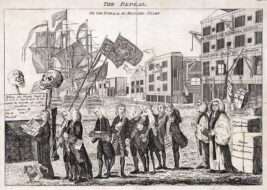

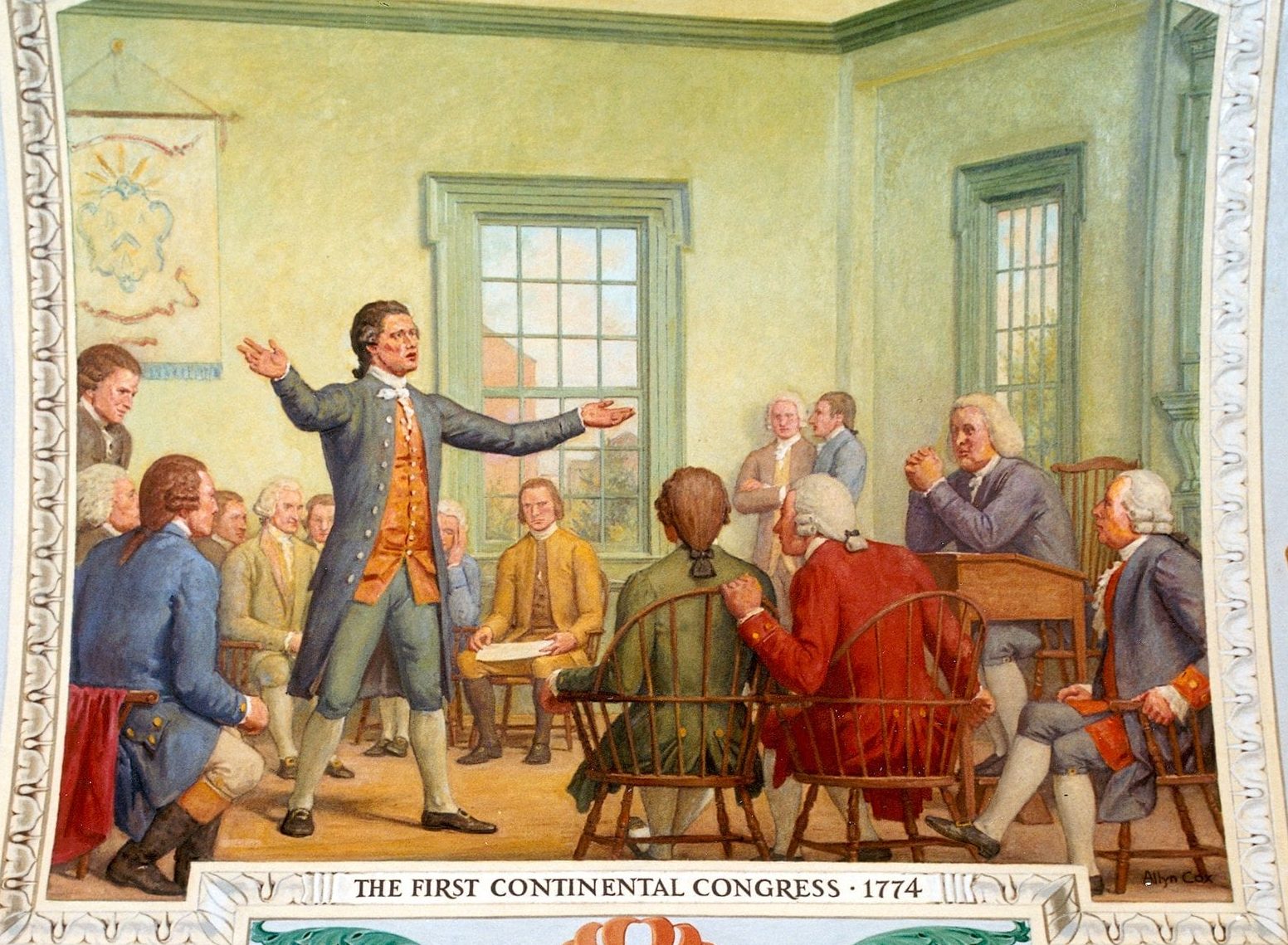

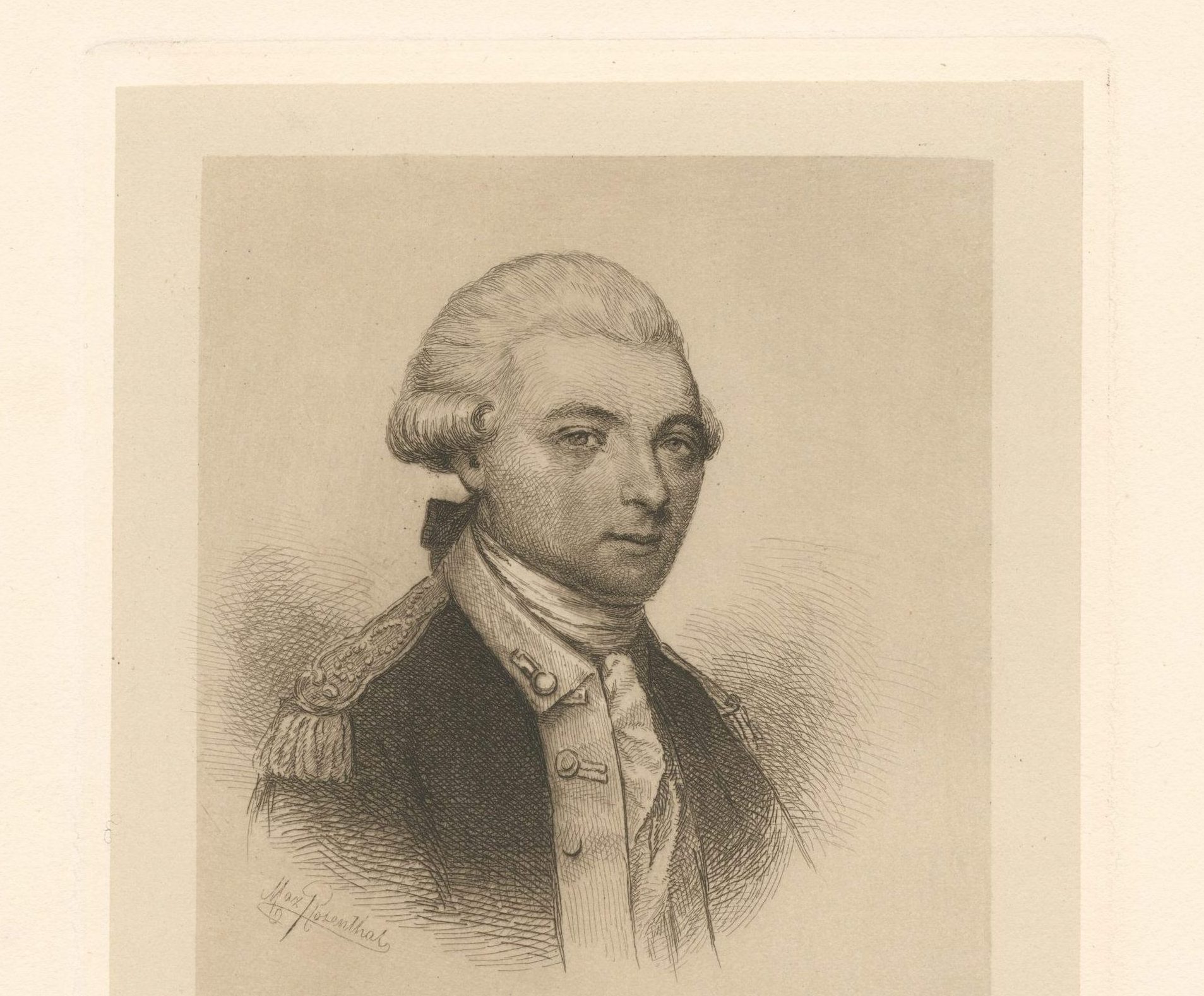

The Continental Congress’s October 1774 passage of the Association (The Association Enacted by the First Continental Congress), which promised to end trade with Great Britain, sparked outrage among moderate colonists wishing for reconciliation with the mother country. Among them was the Reverend Samuel Seabury (1729–1796), an Anglican priest who in the 1760s and early 1770s had supported a controversial proposal to bring a British bishop to America to preside over its churches. Now, writing under the pseudonym “A. W. Farmer” (“A Westchester Farmer”), this New York clergyman lashed out against the Association in a November pamphlet, Free Thoughts on the Proceedings of the Continental Congress. This prompted young Alexander Hamilton (1755/57–1804), a student at King’s College (now Columbia University), to pick up his pen in response. Hamilton’s efforts resulted in the 35-page Full Vindication of the Measures of Congress, signed “A Friend to America” and published on December 15. Less than ten days later, Seabury published this rejoinder.

In 1776, Seabury cast his lot with the Loyalists. He took refuge in British-occupied New York City and in 1778 became chaplain to the King’s American Regiment. After the war Seabury returned to his native Connecticut; in 1784 he became the state’s first Anglican bishop.

Source: A. W. Farmer, A View of the Controversy between Great-Britain and her Colonies (New York: James Rivington, 1774), 17–21, 32–33.

… You, sir, affect to consider the gentlemen that went from this province to the Congress as the representatives of the province. You know in your conscience that they were not chosen by a hundredth part of the people. You know also, that their appointment was in a way unsupported by any law, usage, or custom of the province. You know also, that the people of this province had already delegated their power to the members of their Assembly, and therefore had no right to choose delegates, to contravene the authority of the Assembly, by introducing a foreign power of legislation. Yet you consider those delegates, in a point of light equal to our legal representatives; for you say, that “our representatives in General Assembly cannot take any wiser or better course to settle our differences, than our representatives in the Continental Congress have taken.” Then I affirm, that our representatives ought to go to school for seven years, before they are returned to serve again. No wiser or better course? Then they must take just the course that the Congress have taken; for a worse, or more foolish [course], they cannot take, should they try. If they act any way different from the Congress, they must act better and wiser….

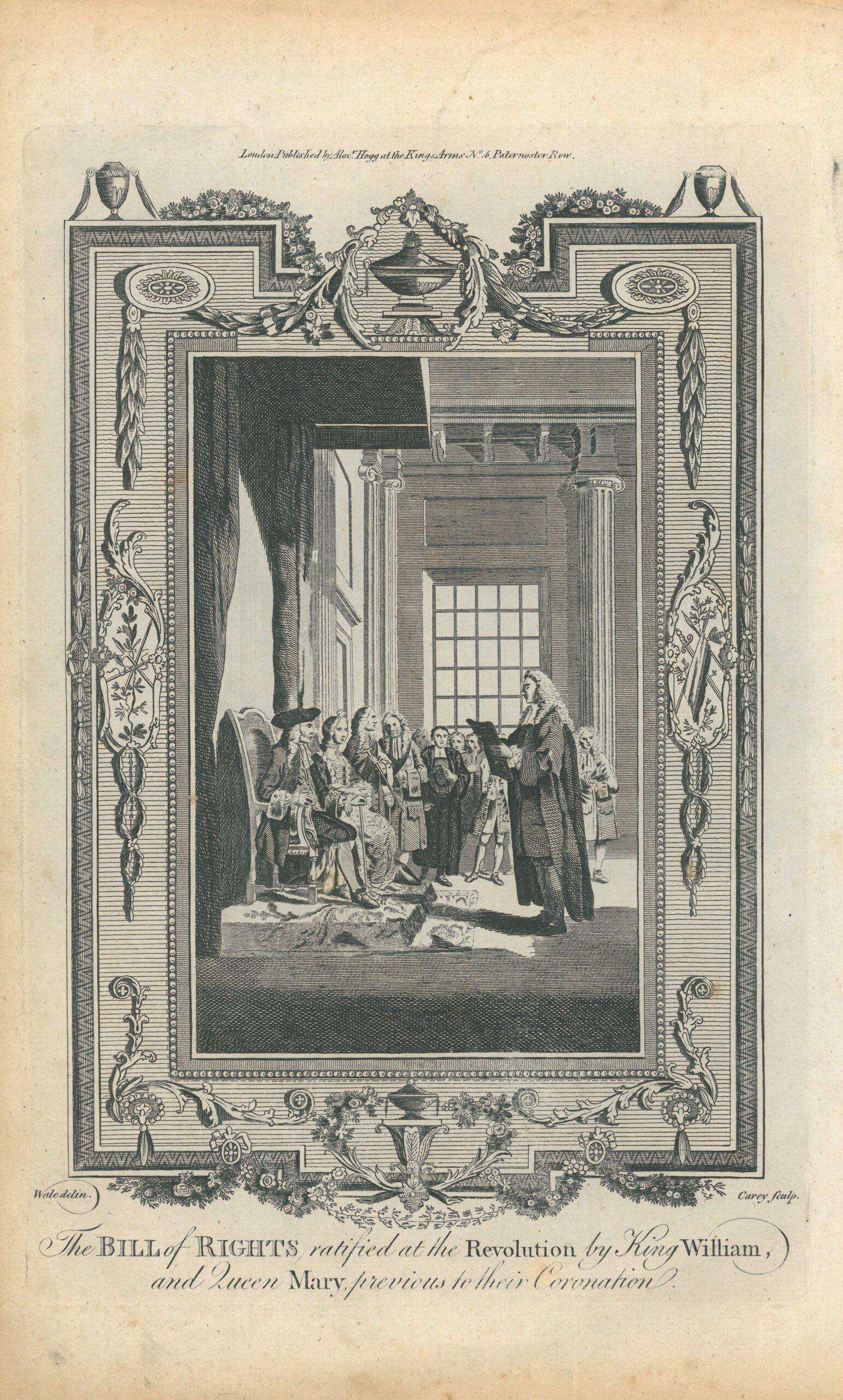

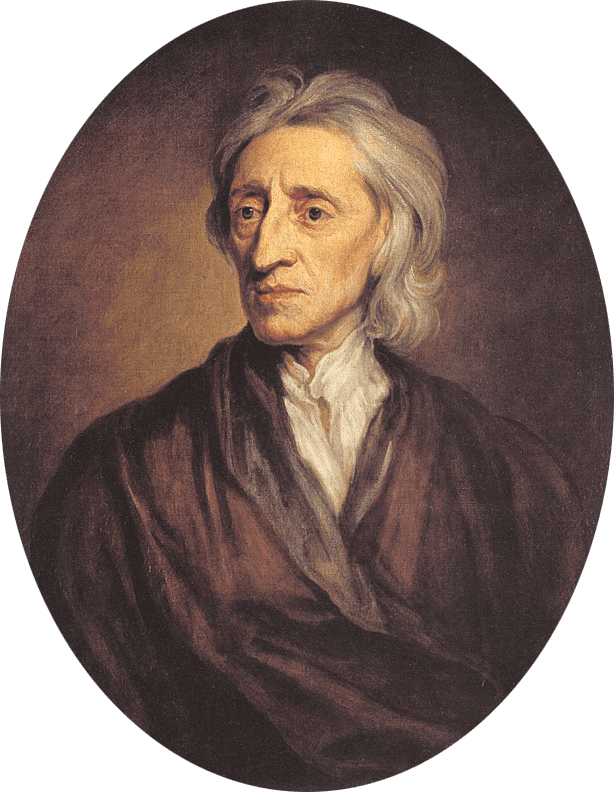

… You, sir, argue through your whole pamphlet, upon an assumed point…. That the British government—the King, Lords, and Commons, have laid a regular plan to enslave America; and that they are now deliberately putting it in execution. This point has never been proved, though it has been asserted over, and over, and over again. If you say, that they have declared their right of making laws, to bind us in all cases whatsoever, I answer; that the declarative act[1] here referred to, means no more than to assert the supreme authority of Great Britain over all her dominions. If you say, that they have exercised this power in a wanton, oppressive manner, it is a point, that I am not enough acquainted with the minutiae of government to determine. It may be true. The colonies are undoubtedly alarmed on account of their liberties. Artful men have availed themselves of the opportunity, and have excited such scenes of contention between the parent state and the colonies, as afford none but dreadful prospects. Republicans[2] smile at the confusion that they themselves have, in a great measure made, and are exerting all their influence, by sedition and rebellion, to shake the British empire to its very basis, that they may have an opportunity of erecting their beloved commonwealth on its ruins. If greater security to our rights and liberties be necessary than the present form and administration of the government can give us, let us endeavor to obtain it; but let our endeavors be regulated by prudence and probability of success. In this attempt all good men will join, both in England and America. All, who love their country, and wish the prosperity of the British empire, will be glad to see it accomplished.

… Every man who wishes well, either to America or Great Britain, must wish to see a hearty and firm union subsisting between them, and between every part of the British empire. The first object of his desire will be to heal the unnatural breach that now subsists, and to accomplish a speedy reconciliation. All parties declare the utmost willingness to live in union with Great Britain. They profess the utmost loyalty to the king; the warmest affection to their fellow subjects in England, Ireland, and the West Indies; and their readiness to do everything to promote their welfare that can reasonably be expected from them. Even those republicans, who wish the destruction of every species and appearance of monarchy in the world, find it necessary to put on a fair face, and make the same declaration.

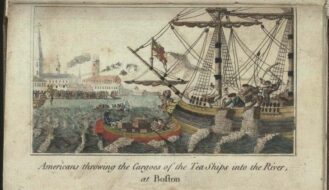

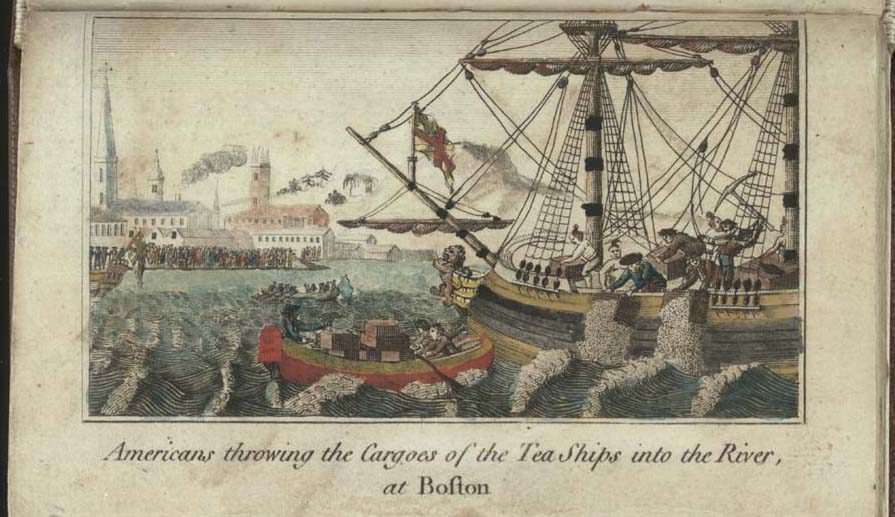

What steps, sir, I beseech you, has the Congress taken to accomplish these good purposes? Have they fixed any determined point for us to aim at? They have, and the point marked out by them, is absolute independence [from] Great Britain—a perfect discharge from all subordination to the supreme authority of the British empire. Have they proposed any method of cementing our union with the mother country? Yes, but a queer one, …to break off all dealings and intercourse with her. Have they done anything to show their love and affection to their fellow subjects in England, Ireland, and the West Indies? Undoubtedly they have—they have endeavored to starve them all to death. Is this “Equity”? Is this “Wisdom”? Then murder is equity, and folly, wisdom.

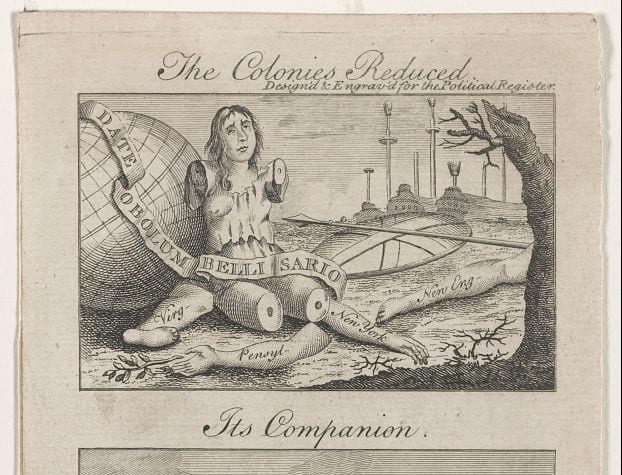

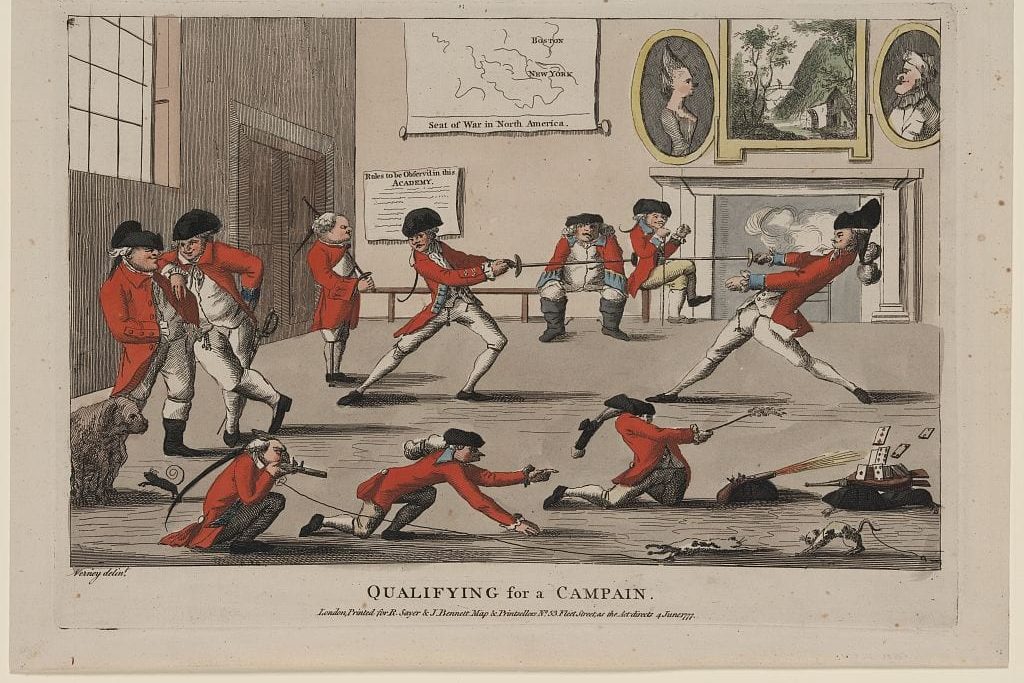

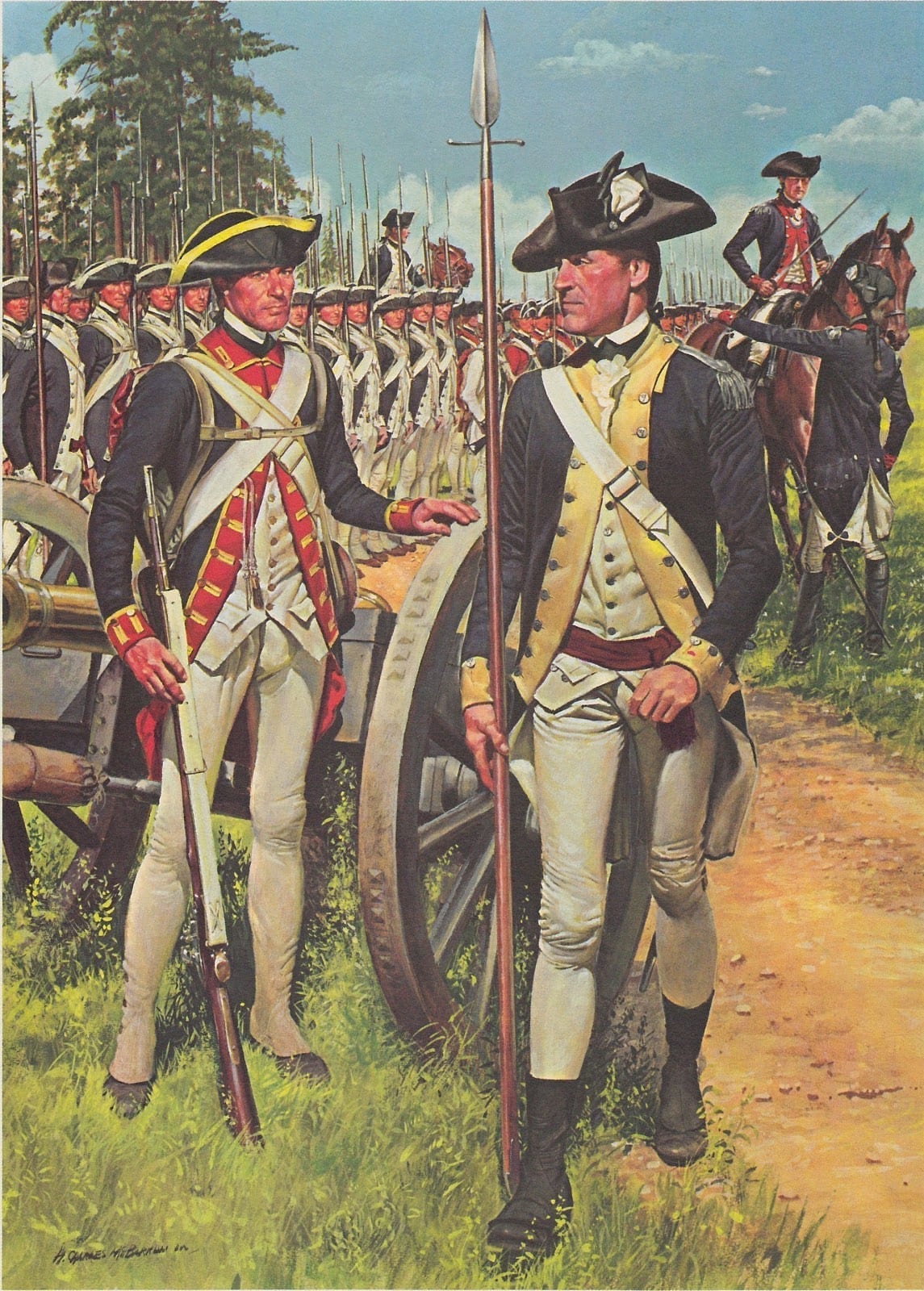

… Do you think, sir, that Great Britain is like an old, wrinkled, withered, worn-out hag, whom every jackanapes[3] that truants along the streets may insult with impunity? You will find her a vigorous matron, just approaching a green old age; and with spirit and strength sufficient to chastise her undutiful and rebellious children. Your measures have as yet produced none of the effects you looked for. Great Britain is not as yet intimidated. She has already a considerable fleet and army in America. More ships and troops are expected in the spring. Every appearance indicates a design in her to support her claim with vigor. You may call it infatuation, madness, frantic extravagance, to hazard so small a number of troops as she can spare, against the thousands of New England. Should the dreadful contest once begin—But God forbid! Save, heavenly Father! O save my country from perdition![4]

Consider, sir, is it right to risk the valuable blessings of property, liberty, and life, to the single chance of war? Of the worst kind of war—a civil war? A civil war founded on rebellion? Without ever attempting the peaceable mode of accommodation? Without ever asking a redress of our complaints, from the only power on earth who can redress them? When disputes happen between nations independent of each other, they first attempt to settle them by their ambassadors; they seldom run hastily to war, until they have tried what can be done by treaty and mediation. I would make many more concessions to a parent, than were justly due to him, rather than engage with him in a duel. But we are rushing into a war with our parent state, without offering the least concession; without even deigning to propose an accommodation. You, sir, have employed your pen, and exerted your abilities, invindicating,[5] and recommending measures which you know must, if persisted in, have a direct tendency to produce and accelerate this dreadful event. The Congress also foresaw the horrid tragedy that must be acted in America, should their measures be generally adopted. Why else did they advise us “to extend our views to mournful events,” and be in all “respects prepared for every contingency?”

May God forgive them, but may he confound their devices: and may he give you repentance and a better mind!…

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.