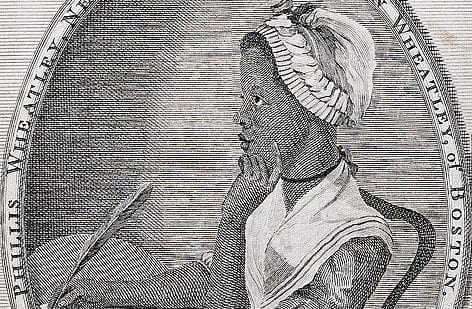

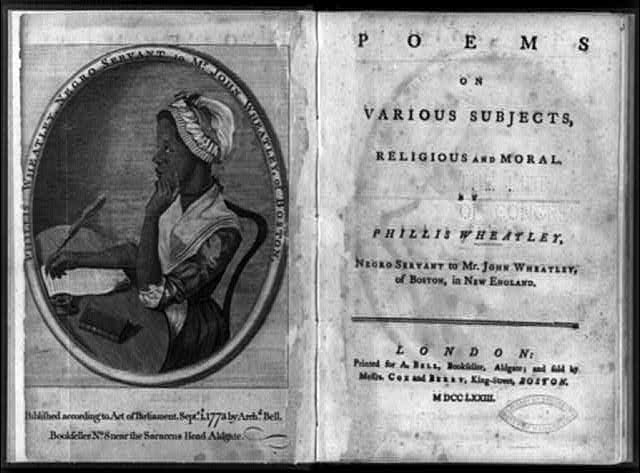

Source: Phillis Wheatley, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (London, 1773), 18, 22–24; The Pennsylvania Magazine: or, American Monthly Museum, 2 (April 1776), 193. We have modernized spelling and capitalization.

On being brought from Africa to America

’TWAS mercy brought me from my pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there’s a God, that there’s a Savior too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

“Their color is a diabolic die.”

Remember, Christians, Negroes, black as Cain,

May be refined, and join the angelic train.

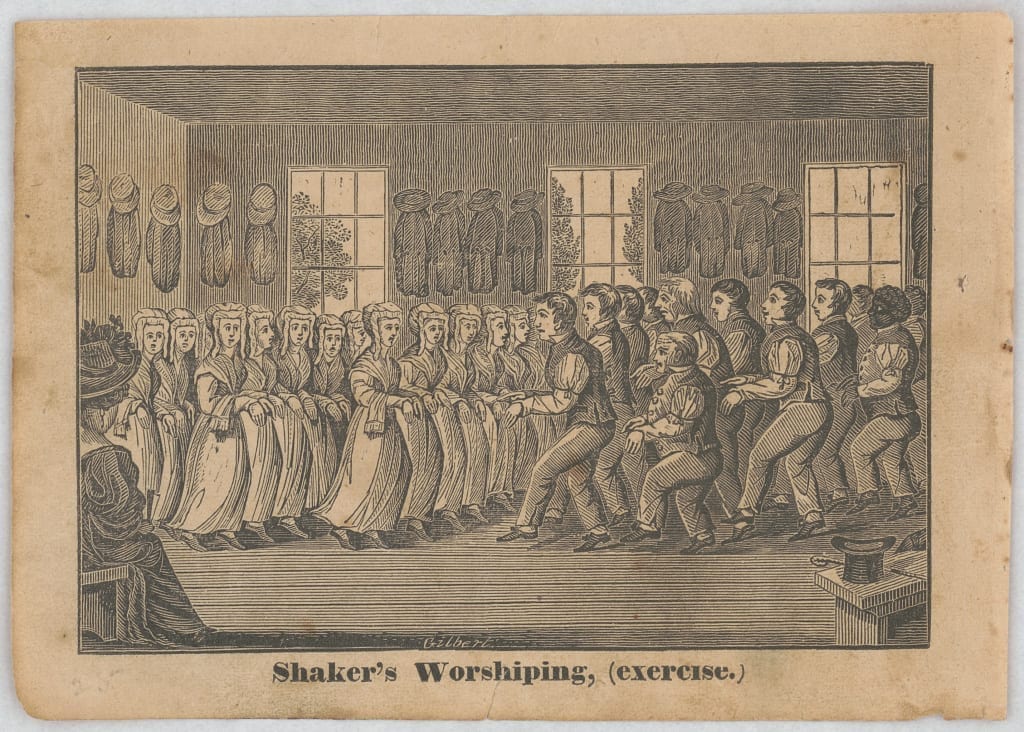

On the Death of the Rev. Mr. GEORGE WHITEFIELD (c. 1770)

HAIL, happy saint, on your immortal throne,

Possessed of glory, life, and bliss unknown;

We hear no more the music of your tongue,

Your wonted auditories cease to throng.

Your sermons in unequalled accents flowed,

And every bosom with devotion glowed;

You did in strains of eloquence refined

Inflame the heart, and captivate the mind.

Unhappy we the setting sun deplore,

So glorious once, but ah! it shines no more.

Behold the prophet in his towering flight!

He leaves the earth for heaven’s unmeasured height,

And worlds unknown receive him from our sight.

There Whitefield wings with rapid course his way,

And sails to Zion through vast seas of day.

Your prayers, great saint, and your incessant cries

Have pierced the bosom of your native skies.

Your moon has seen, and all the stars of light,

How he has wrestled with his God by night.

He prayed that grace in every heart might dwell,

He longed to see America excel;

He charged its youth that every grace divine

Should with full luster in their conduct shine;

That Savior, which his soul did first receive,

The greatest gift that even a God can give,

He freely offered to the numerous throng,

That on his lips with listening pleasure hung.

“Take him, you wretched, for your only good,

Take him you starving sinners, for your food;

You thirsty, come to this life-giving stream,

You preachers, take him for your joyful theme;

Take him my dear Americans,” he said,

“Be your complaints on his kind bosom laid:

Take him, you Africans, he longs for you,

Impartial Savior is his title due:

Washed in the fountain of redeeming blood,

You shall be sons, and kings, and priests to God.”

Great countess,* we Americans revere

Your name, and mingle in your grief sincere;

New England deeply feels, the orphans mourn,

Their more than father will no more return.

But, though arrested by the hand of death,

Whitefield no more exerts his laboring breath,

Yet let us view him in the eternal skies,

Let every heart to this bright vision rise;

While the tomb safe retains its sacred trust,

Till life divine re-animates his dust.

*The Countess of Huntingdon, to whom Mr. Whitefield was Chaplain. [in original]

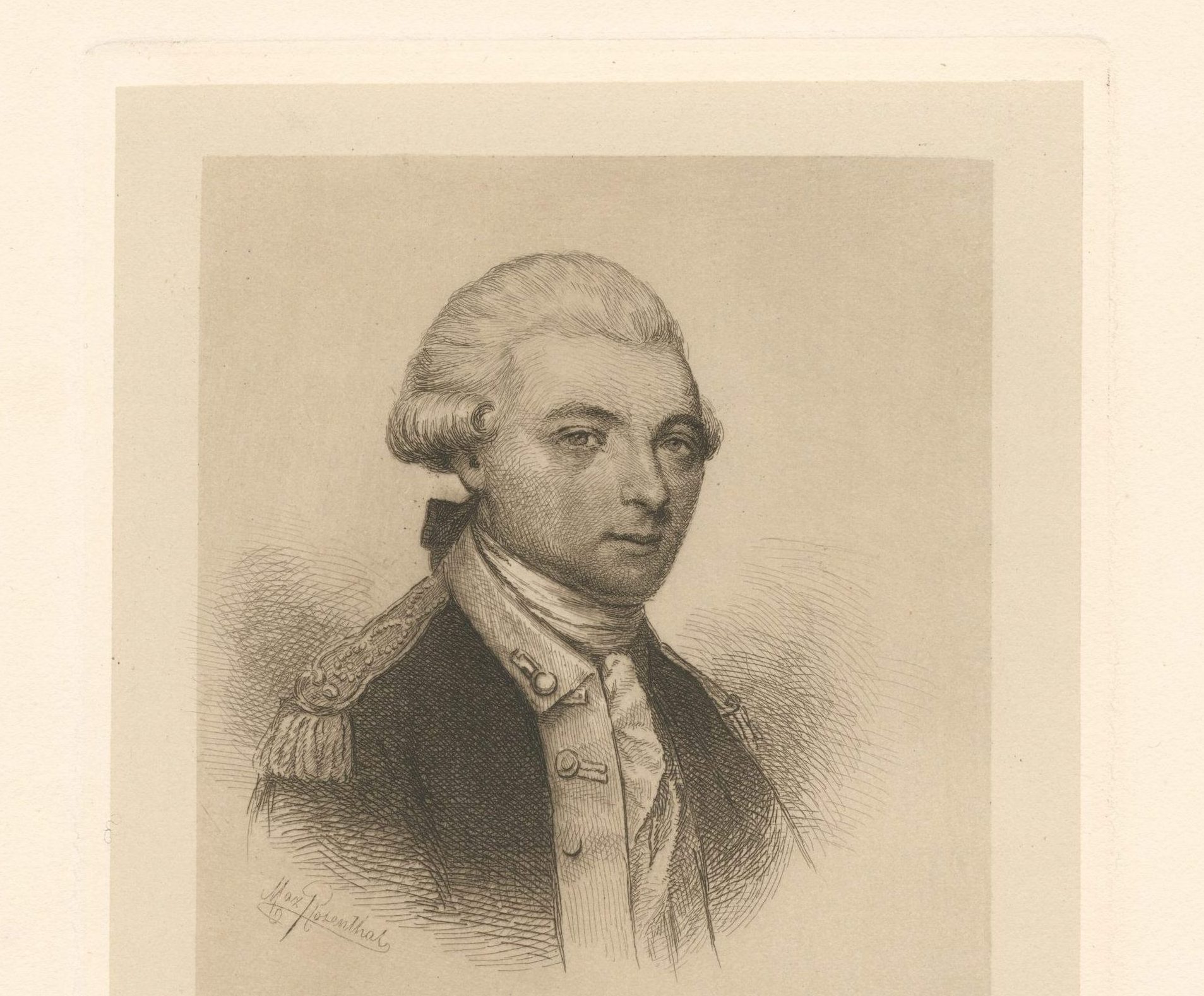

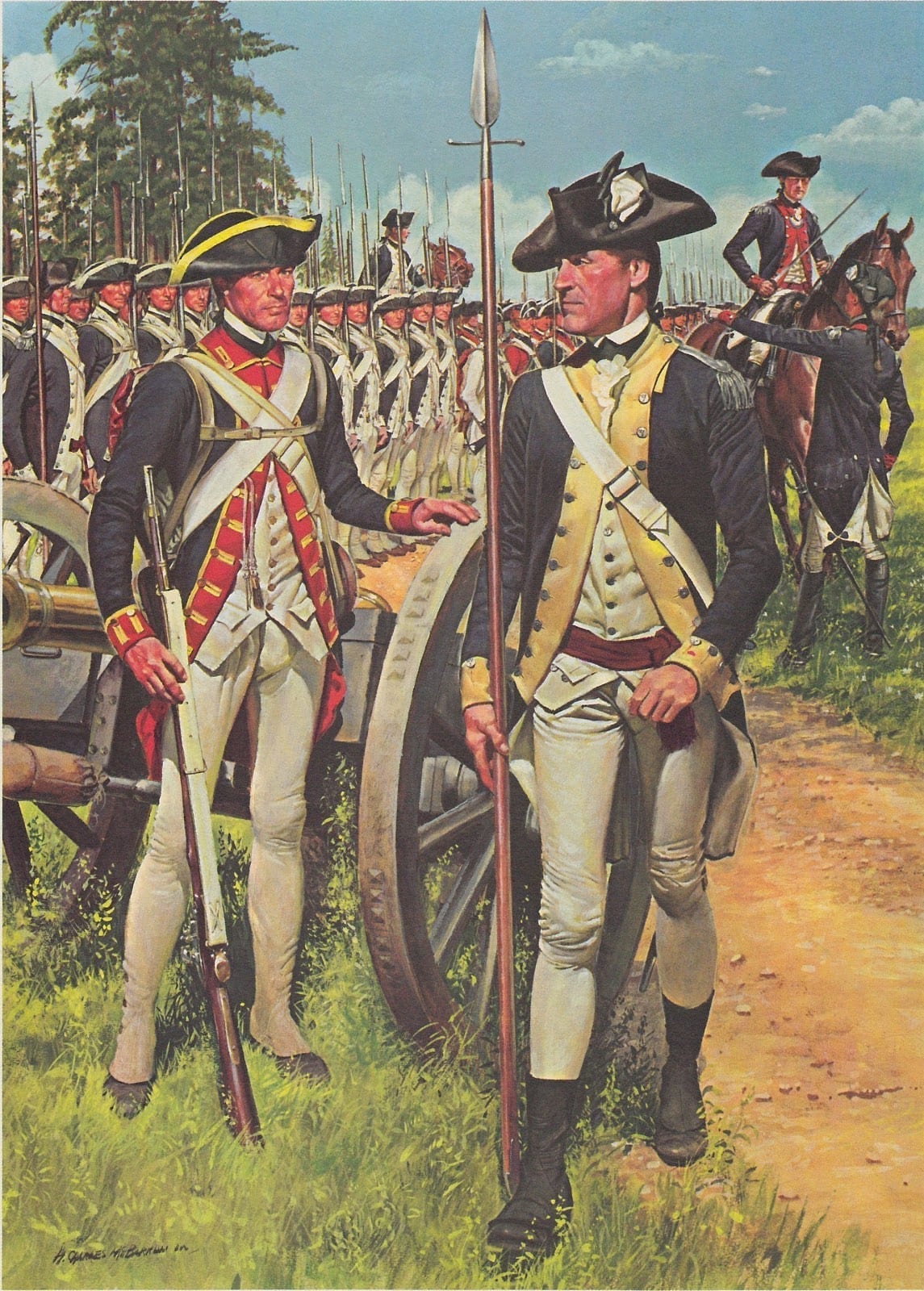

To His Excellency General Washington (26 October 1775)

Celestial choir! enthroned in realms of light,

Columbia’s scenes of glorious toils I write.

While freedom’s cause her anxious breast alarms,

She flashes dreadful in refulgent arms.

See mother earth her offspring’s fate bemoan,

And nations gaze at scenes before unknown!

See the bright beams of heaven’s revolving light

Involved in sorrows and the veil of night!

The goddess comes, she moves divinely fair,

Olive and laurel binds her golden hair:

Wherever shines this native of the skies,

Unnumbered charms and recent graces rise.

Muse! bow propitious while my pen relates

How pour her armies through a thousand gates:

As when Eolus heaven’s fair face deforms,

Enwrapped in tempest and a night of storms;

Astonished ocean feels the wild uproar,

The refluent surges beat the sounding shore;

Or thick as leaves in Autumn’s golden reign,

Such, and so many, moves the warrior’s train.

In bright array they seek the work of war,

Where high unfurled the ensign waves in air.

Shall I to Washington their praise recite?

Enough you know them in the fields of fight.

You, first in place and honors,—we demand

The grace and glory of your martial band.

Famed for thy valor, for your virtues more,

Hear every tongue your guardian aid implore!

One century scarce performed its destined round,

When Gallic powers Columbia’s fury found;

And so may you, whoever dares disgrace

The land of freedom’s heaven-defended race!

Fixed are the eyes of nations on the scales,

For in their hopes Columbia’s arm prevails.

Anon Britannia droops the pensive head,

While round increase the rising hills of dead.

Ah! cruel blindness to Columbia’s state!

Lament your thirst of boundless power too late.

Proceed, great chief, with virtue on your side,

Your every action let the goddess guide.

A crown, a mansion, and a throne that shine,

With gold unfading, Washington! be yours.