Introduction

When the Virginia colony was founded in 1607, the majority of unfree laborers in the colony were indentured servants, men and women who signed a legal contract called an indenture that bound them to work for a certain individual for a certain number of years, in exchange for which they received room, board, and some type of education or training. During their indenture, the servant was legally subject to the rule of their master; although there were laws to protect servants, Virginia’s spread-out settlements meant that working conditions in actuality varied widely. No matter how oppressive their master, however, at the end of their indenture period, the individual servant was free to leave (usually with a set of supplies and a sum of money adequate for starting out on his or her own way in the world).

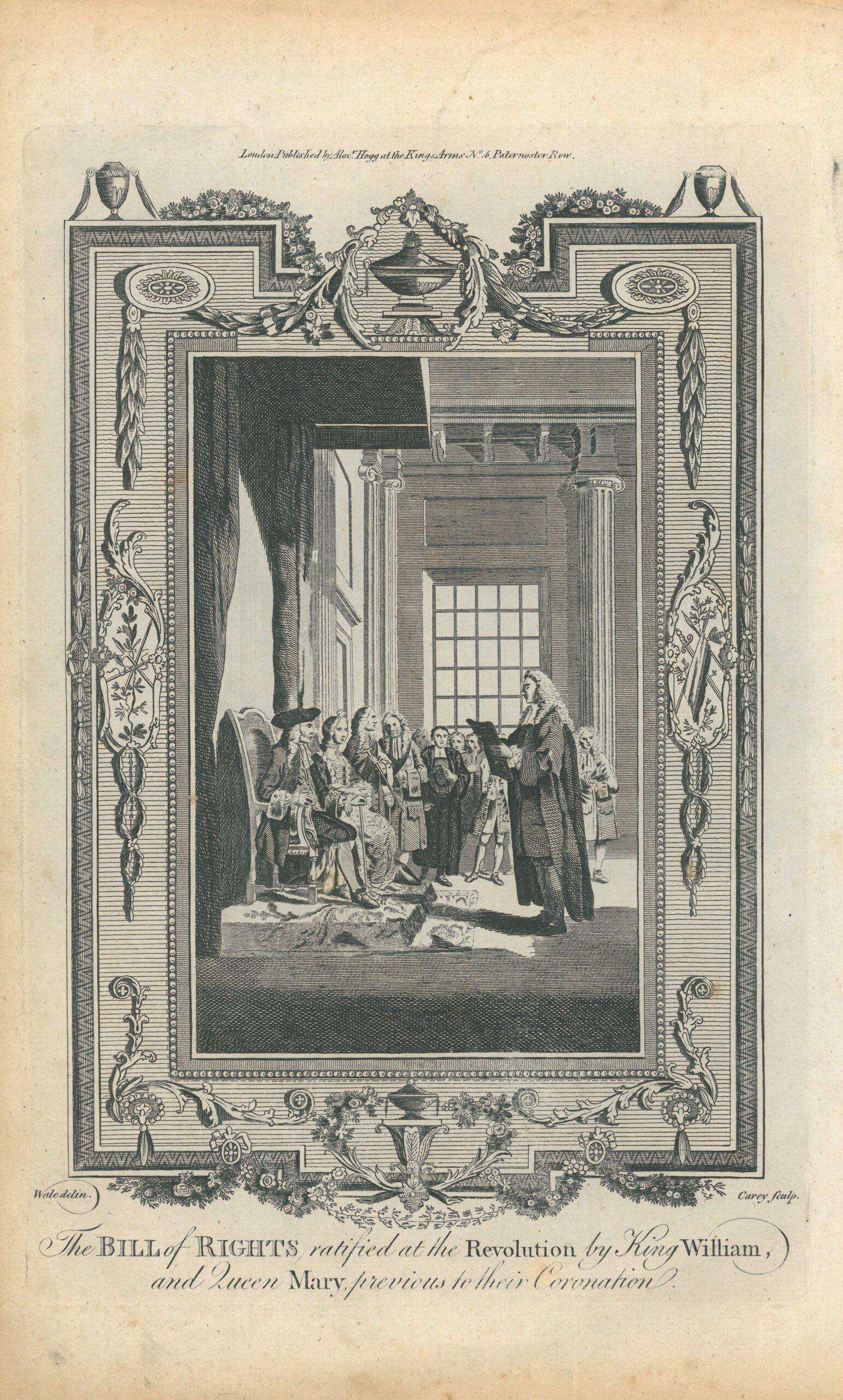

The second class of unfree labor consisted of slaves. At the beginning of the colonial period, records indicate that the most significant difference between slavery and indentured servitude lay in the expectation that, in the latter case, the individual would receive the sort of training and tools necessary to eventually take their place as a free person. In the early seventeenth century, race-based slavery for life did not exist in the Anglo-American world. Instead, where it existed, slavery was linked to the cultural and religious background of the enslaved person: non-Christian captives taken in a war, for example, might be enslaved, but not Christians, regardless of their racial or ethnic background. Nor was slavery always a permanent and inheritable condition: in the early years of the colony, individual slaves were able to win their freedom by demonstrating proof of their conversion to Christianity; in addition, enslaved persons were sometimes able to arrange to purchase their freedom, and policies regarding the status of children born to enslaved persons remained in flux until the mid-seventeenth century.

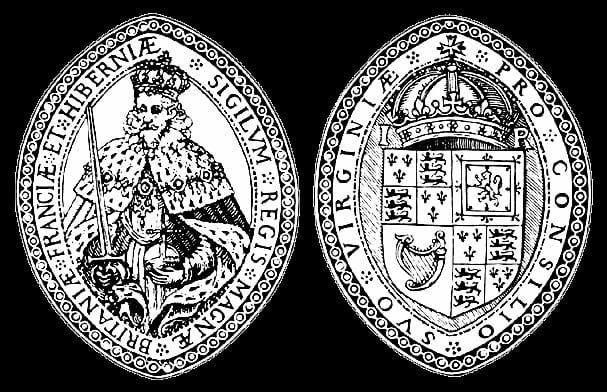

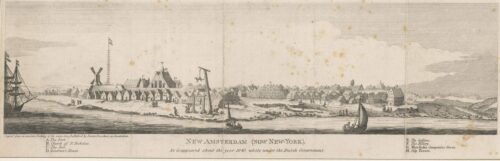

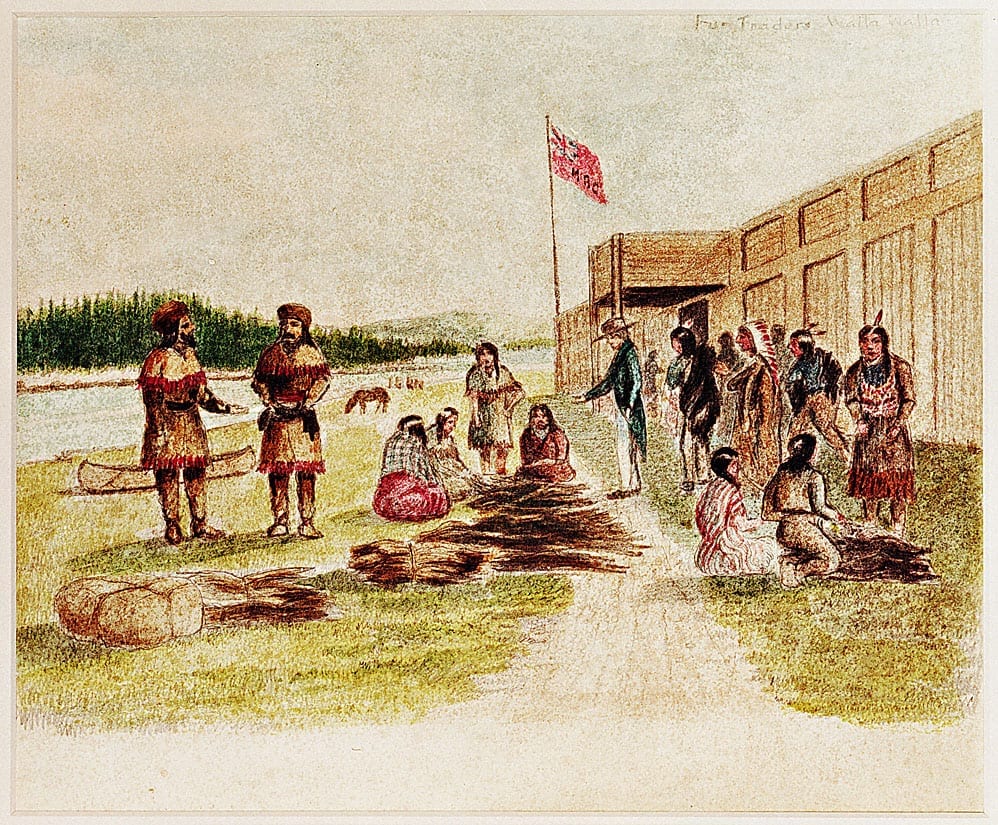

From the beginning, both forms of unfree labor coexisted in Virginia: the funders of the colony relied upon a mix of incentives (free land in exchange for a period of labor) and the bad economy in England to encourage laborers to come to the new colony as indentured servants, while the colonists took captives as slave hostages during their frequent conflicts with the local native population. The first slaves from Africa arrived at Jamestown in 1619.

Initially, the majority of the colony’s labor force consisted of indentured servants, but over time, as the English expanded their participation in the Atlantic and Indian slave trades and market conditions in the mother country improved, the balance shifted. By the end of the 1670s, black slaves began to replace both white indentured servants and Indian slaves as Virginians’ primary source of labor.

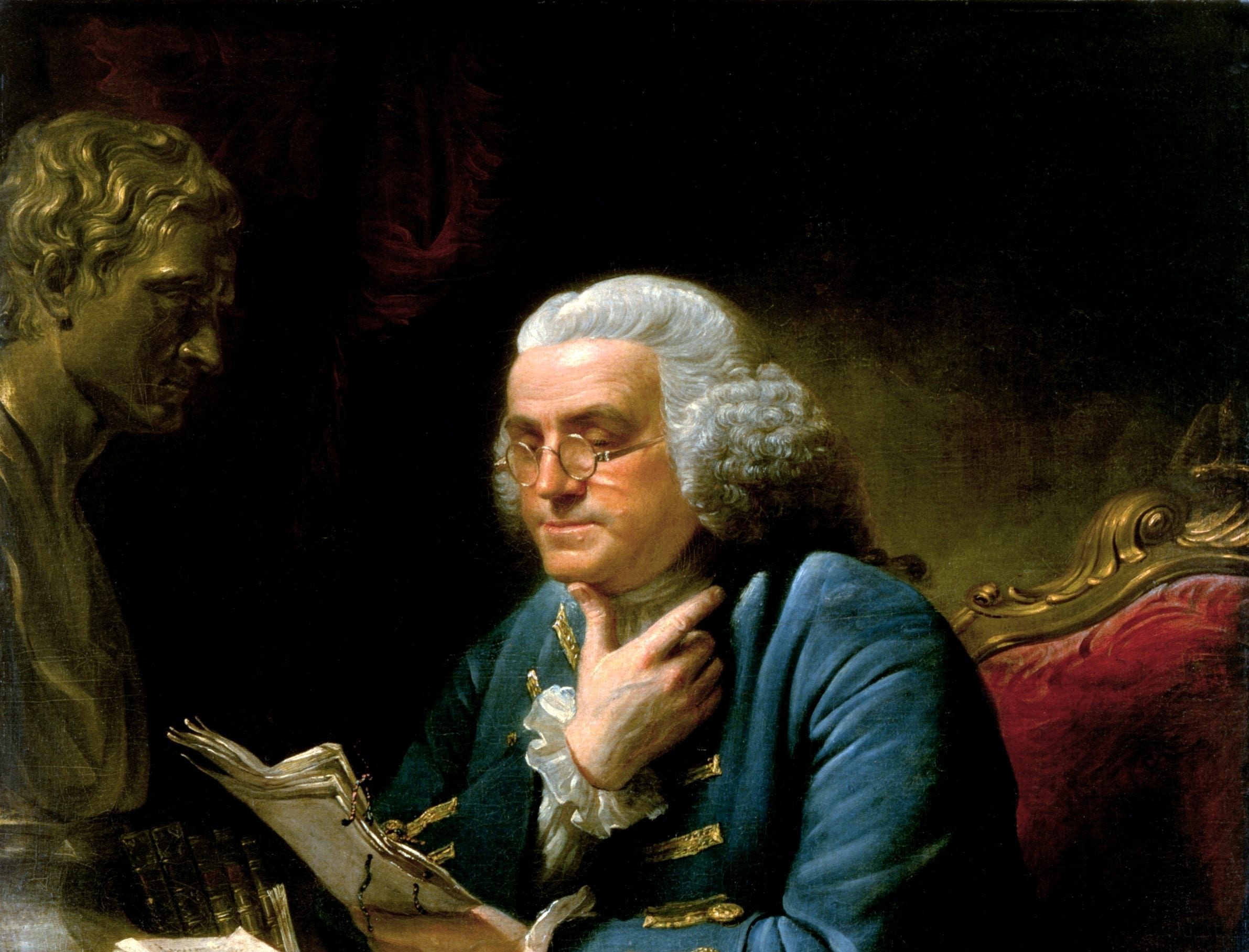

Robert Beverley, The History of Virginia, Part 4, Chapter 10 (London: B. and S. Tooke, 1722), 235-239. Online: https://goo.gl/QCyT67. Robert Beverly (c. 1662–1722) was a prominent landowner and political figure.

§50. Their servants they distinguish by the names of slaves for life, and servants for a time.

Slaves are the negroes, and their posterity, following the condition of the mother, according to the maxim, partus sequitur ventrem. They are called slaves, in respect of the time of their servitude, because it is for life.

Servants, are those which serve only for a few years, according to the time of their indenture, or the custom of the country. The custom of the country takes place upon such as have no indentures. The law in this case is, that if such servants be under nineteen years of age, they must be brought into court, to have their age adjudged; and from the age they are judged to be of, they must serve until they reach four and twenty: But if they be adjudged upwards of nineteen, they are then only to be Servants for the term of five years.

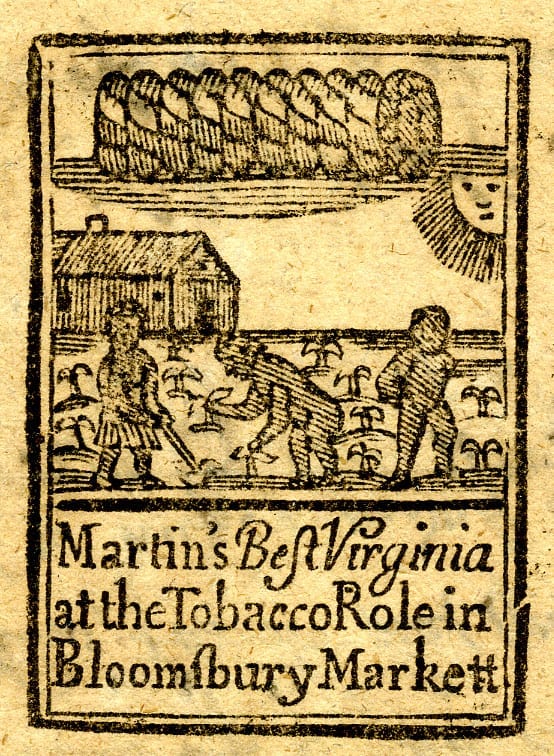

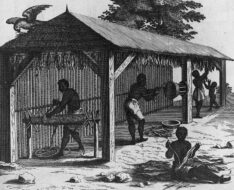

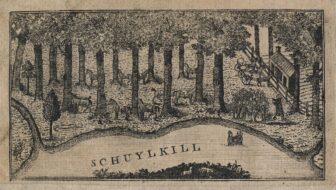

§51. The male-servants, and slaves of both sexes, are employed together in tilling and manuring the ground, in sowing and planting tobacco, corn, etc. Some distinction indeed is made between them in their clothes, and food; but the work of both is no other than what the overseers, the freemen, and the planters themselves do.

Sufficient distinction is also made between the female-servants, and slaves; for a white woman is rarely or never put to work in the ground, if she be good for anything else: and to discourage all planters from using any women so, their law makes female-servants working in the ground tithables, while it suffers all other white women to be absolutely exempted: whereas on the other hand, it is a common thing to work a woman slave out of doors; nor does the law make any distinction in her taxes, whether her work be abroad, or at home.

§52. Because I have heard how strangely cruel, and severe, the service of this country is represented in some parts of England; I can’t forbear affirming, that the work of their servants and slaves is no other than what every common freeman does. Neither is any servant required to do more in a day, than his overseer. And I can assure you with great truth, that generally their slaves are not worked near so hard, nor so many hours in a day, as the husbandmen, and day-labourers in England. An overseer is a man, that having served his time, has acquired the skill and character of an experienced planter, and is therefore entrusted with the direction of the servants and slaves.

But to complete this account of servants, I shall give you a short relation of the care their laws take, that they be used as tenderly as possible.

By the Laws of their Country.

- All Servants whatsoever have their complaints heard without fee, or reward; but if the master be found faulty, the charge of the complaint is cast upon him, otherwise the business is done ex officio.

- Any Justice of Peace may receive the complaint of a servant, and order everything relating thereto, till the next County-Court, where it will be finally determined.

- All masters are under the correction and censure of the County-Courts, to provide for their servants good and wholesome diet, clothing and lodging.

- They are always to appear upon the first notice given of the complaint of their servants, otherwise to forfeit the service of them, until they do appear.

- All servants’ complaints are to be received at any time in Court, without process, and shall not be delayed for want of form; but the merits of the complaint must be immediately inquired into by the justices; and if the master cause any delay therein, the Court may remove such servants, if they see cause, until the master will come to Trial.

- If a master shall at any time disobey an Order of Court made upon any complaint of a servant; the Court is empowered to remove such servant forthwith to another master, who will be kinder; giving to the former master the produce only, (after fees deducted) of what such servants shall be sold for by public outcry.

- If a master should be so cruel, as to use his servant ill, that is fallen sick, or lame in his, and thereby rendered unfit for labour, he must be removed by the church-wardens out of the way of such cruelty, and boarded in some good planter’s house, till the time of his freedom, the charge of which must be laid before the next County-Court, which has power to levy the same from time to time, upon the goods and chattels of the master; after which, the charge of such boarding is to come upon the parish in general.

- All hired servants are entitled to these privileges.

- No master of a servant can make a new bargain for service, or other matter with his servant, without the privity and consent of the County-Court, to prevent the masters over-reaching, or scaring such servant into an unreasonable compliance.

- The property of all money and goods sent over thither to servants, or carried in with them; is reserved to themselves, and remains entirely at their disposal.

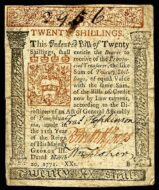

- Each servant at his freedom receives of his master ten bushels of corn, (which is sufficient for almost a year) two new suits of clothes, both linen and woollen, and a gun 20 s[hillings] value, and then becomes as free in all respects, and as much entitled to the liberties and privileges of the country, as any other of the inhabitants or natives are, if such servants were not aliens.

- Each servant has then also a right to take up fifty acres of land, where he can find any unpatented.

This is what the laws prescribe in favour of servants, by which you may find, that the cruelties and severities imputed to that country, are an unjust reflection. For no people more abhor the thoughts of such usage, than the Virginians, nor take more Precaution to prevent it now, whatever it was in former Days.