No related resources

Introduction

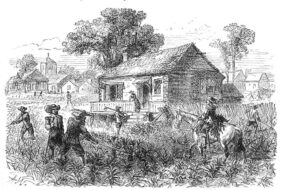

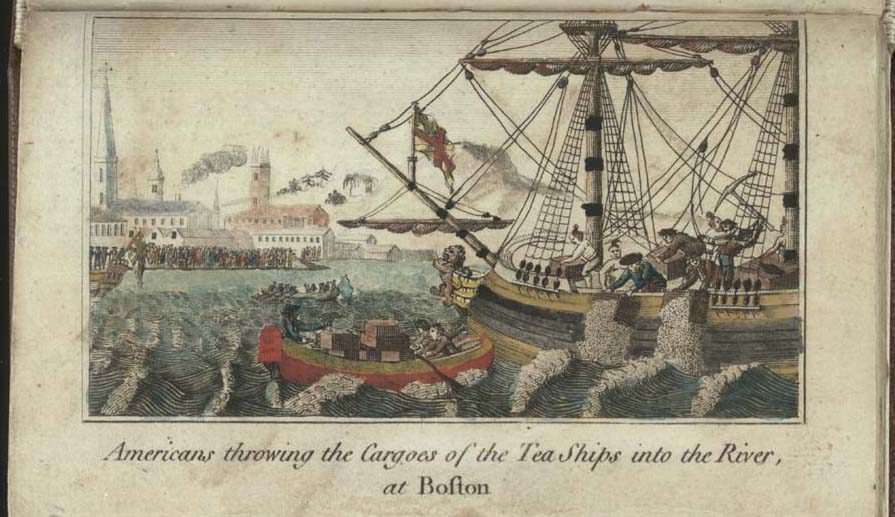

The Townshend Acts resulted in colonists’ nonimportation agreements. The enforcement of these pacts sometimes resulted in violence. On February 22, 1770, when a group of Boston teenagers placed a sign in front of the shop of merchant Theophilus Lillie noting his status as an “IMPORTER,” an angry crowd gathered. Ebenezer Richardson (1718–?), a customs employee who tried but failed to remove the sign, succeeded in attracting the scorn of the mob, which followed him home. As his house shook and his windows shattered, Richardson panicked and fired his shotgun into the crowd, killing 10-year-old Christopher Seider (1759–1770).

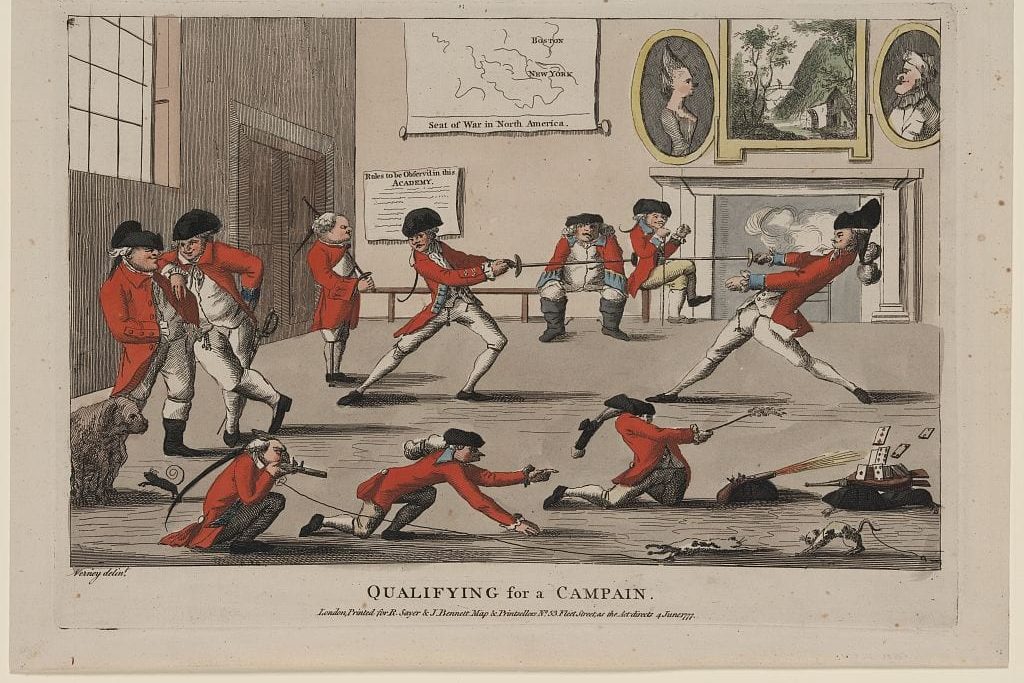

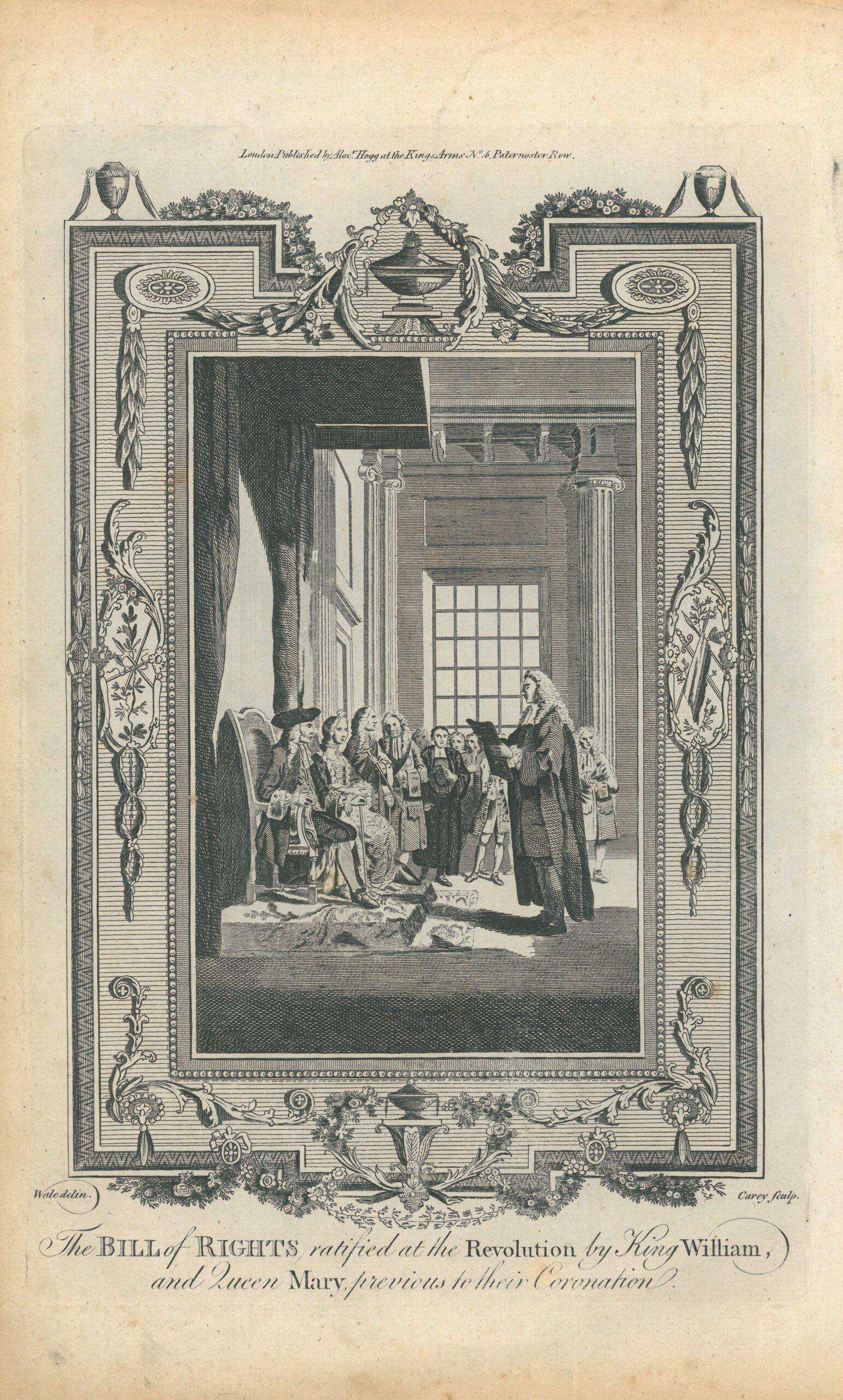

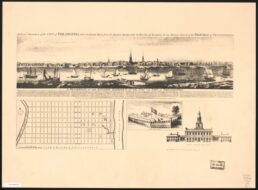

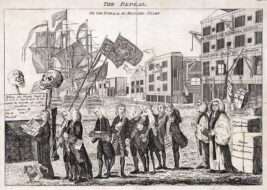

Seider’s death sparked outrage in Boston. The presence of British troops, who had arrived in 1768, did nothing to defuse tensions. By 1770, there was one Redcoat for every four of the city’s 16,000 inhabitants. Off-duty soldiers and civilians sometimes brawled in the streets, as on the nights of Friday, March 2, and Saturday, March 3. On Monday, March 5, Lord North (1732–1792), the new prime minister (1770–1782), introduced in Parliament a bill repealing most of the taxes imposed by the Townshend Acts. Yet this act, meant to improve relations between Britain and its colonies, would be overshadowed by the Boston Massacre, which occurred that same evening.

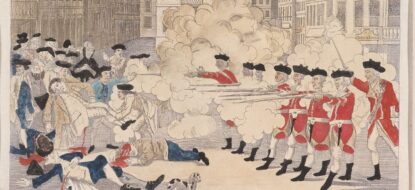

Taken together, accounts of the night’s events make clear the basic details of the “massacre.” Angry Bostonians surrounded a Redcoat sentry who stood at the door of the customhouse. They hurled snowballs, ice, and insults. He returned the crowd’s strong words. The crowd grew—and grew angrier. Church bells rang, summoning additional people, many of whom carried buckets because they thought the bells signaled a nearby fire. Captain Thomas Preston (c. 1722–c. 1798), who had been watching from a distance, marched with seven soldiers, bayonets fixed to their muskets, to rescue the sentry. Soon all nine of these Redcoats had their backs to the wall of the customhouse. In this chaos, Preston later testified, he ordered his men not to fire their half-cocked muskets. Meanwhile, people in the noisy crowd yelled “Fire!” One soldier, hit by a chunk of ice, discharged his musket. The other soldiers then fired as well. The soldiers wounded 11 members of the mob. Three died within minutes. Another died hours later. A fifth died after several days.

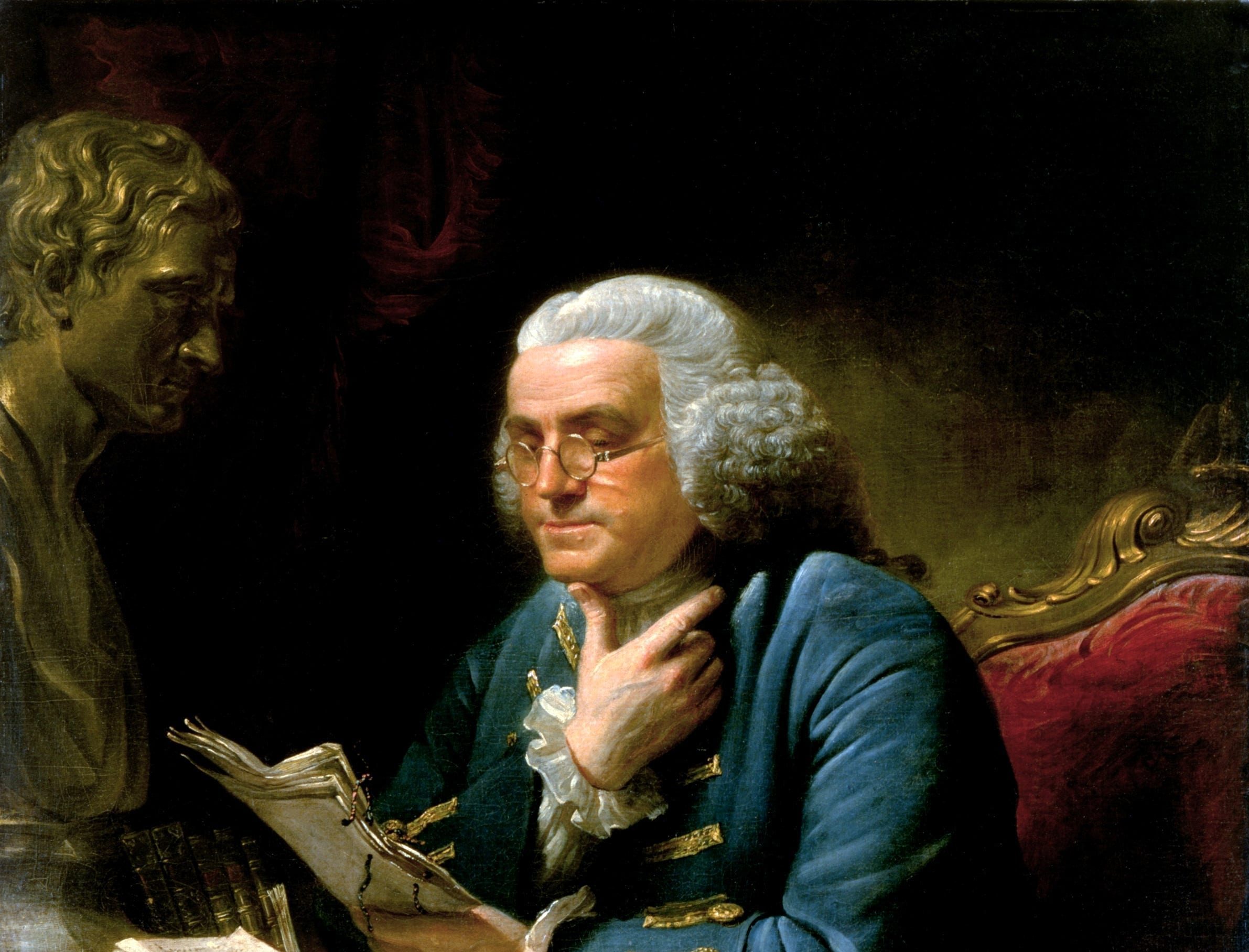

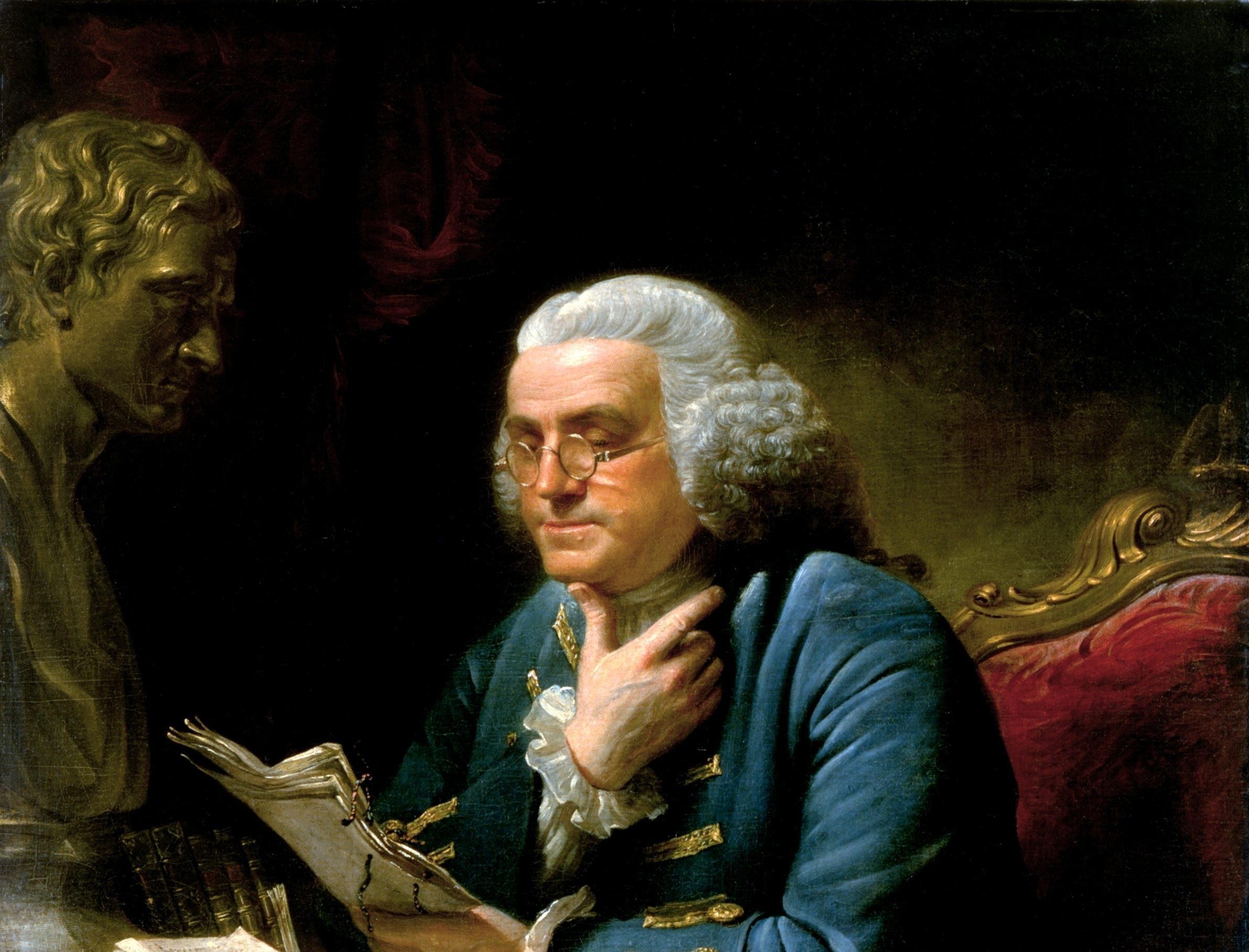

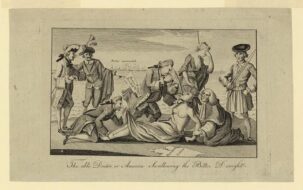

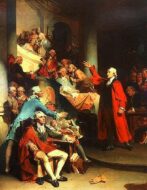

In October and November, in two separate trials, John Adams (1735–1826) served as defense attorney for Preston and his men. Presented with the testimony of multiple witnesses, a jury found Preston not guilty. Another jury found all but two of his men not guilty; the others were convicted of manslaughter, branded with an “M” between the thumb and index finger, and released. The British fared more poorly in the court of public opinion. A depiction popularized by the engraving of Paul Revere (1734–1818) showed Preston ordering his men to fire and the victims with their backs against the wall (see illustration). Meanwhile, merchant John Tudor (1709–1795), a deacon at the Second Church of Boston, recorded in his diary what he had seen and heard about the incident and its aftermath. As news of the massacre spread, more and more Americans wondered if the British government, entrusted to protect their lives, liberty, and property, in fact posed a grievous threat to those essential rights.

Source: William Tudor, ed., Deacon Tudor’s Diary…. (Boston: Wallace Spooner, 1896), 30–34. https://archive.org/details/deacontudorsdiar00tudo/page/n79

On Monday evening, the 5th current, a few minutes after 9 o’clock, a most horrid murder was committed in King Street before the customhouse door by 8 or 9 soldiers under the command of Captain Thomas Preston, drawn off from the main guard on the south side of the townhouse.

March 5 [Monday]

This unhappy affair began by some boys and young fellows throwing snowballs at the sentry placed at the customhouse door. On which 8 or 9 soldiers came to his assistance. Soon after a number of people collected, when the captain commanded the soldiers to fire, which they did and 3 men were killed on the spot and several mortally wounded, one of which died [the] next morning. The captain soon drew off his soldiers up to the main guard, or the consequences might have been terrible, for on the guns firing the people were alarmed and set the bells ringing as if for fire, which drew multitudes to the place of action. Lieutenant Governor [Thomas] Hutchinson, who was commander in chief, was sent for and came to the council chamber, where some of the magistrates attended. The [lieutenant] governor desired the multitude about 10 o’clock to separate and go home peaceable and he would do all in his power that justice should be done, etc…. The people insisted that the soldiers should be ordered to their barracks 1st before they would separate, which being done the people separated about 1 o’clock….

Captain Preston was taken up by a warrant… and we sent him to jail soon after 3, having evidence sufficient to commit him, on his ordering the soldiers to fire….

[March 6, Tuesday]

The next forenoon the 8 soldiers that fired on the inhabitants were also sent to jail. Tuesday A.M. the inhabitants met at Faneuil Hall and after some pertinent speeches, chose a committee of 15 gentlemen to wait on the lieutenant governor in council to request the immediate removal of the troops. The message was in these words. That it is the unanimous opinion of this meeting that the inhabitants and soldiery can no longer live together in safety; that nothing can rationally be expected to restore the peace of the town and prevent blood and carnage but the removal of the troops; and that we most fervently pray his honor that his power and influence may be exerted for their instant removal. His honor’s reply was, gentlemen I am extremely sorry for the unhappy difference and especially of the last evening, and signifying that it was not in his power to remove the troops, etc., etc.

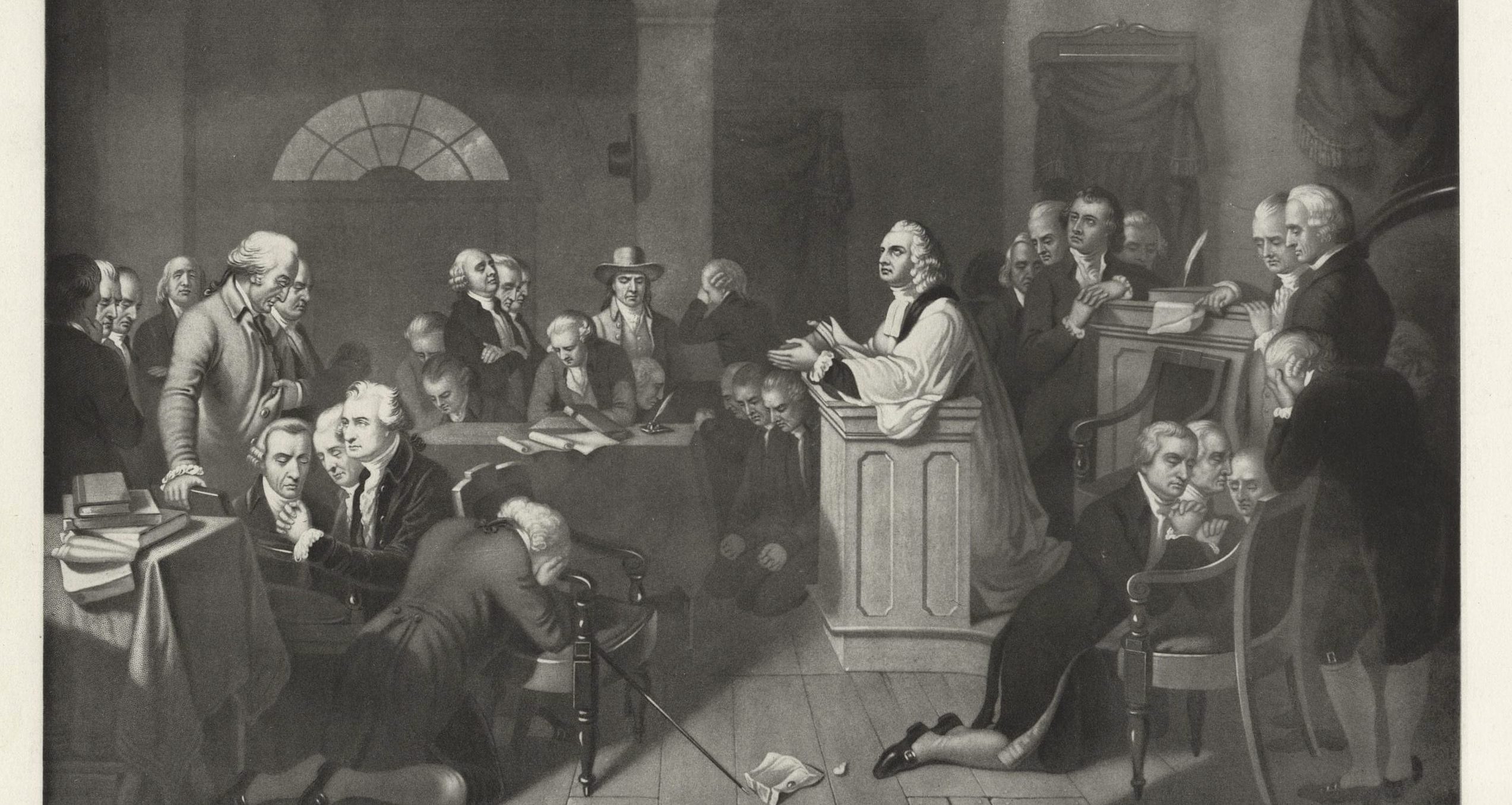

The above reply was not satisfactory to the inhabitants, as but one regiment should be removed to the Castle Barracks.[1] In the afternoon the town adjourned to Dr. Sewill’s Meetinghouse,[2] for Faneuil Hall was not large enough to hold the people, there being at least 3,000, some supposed near 4,000, when they chose a committee to wait on the lieutenant governor to let him and the council know that nothing less will satisfy the people than a total and immediate removal of the troops out of the town.

His honor laid before the council the vote of the town. The council thereon expressed themselves to be unanimously of [the] opinion that it was absolutely necessary for his majesty’s service, the good order of the town, etc., that the troops should be immediately removed out of the town.

His honor communicated this advice of the council to Colonel Dalrymple[3] and desired he would order the troops down to Castle William. After the colonel had seen the vote of the council he gave his word and honor to the town’s committee that both the regiments should be removed without delay. The committee returned to the town meeting and Mr. Hancock,[4] chairman of the committee, read their report as above, which was received with a shout and clap of hands, which made the meetinghouse ring….

March 8 (Thursday)

Agreeable to a general request of the inhabitants, were followed to the grave (for they were all buried in one) in succession the 4 bodies of Messrs. Samuel Gray, Samuel Maverick, James Caldwell, and Crispus Attucks, the unhappy victims who fell in the bloody massacre.[5] On this sorrowful occasion most of the shops and stores in town were shut, all the bells were ordered to toll a solemn peal in Boston, Charleston, Cambridge, and Roxbury. The several hearses forming a junction in King Street, the theater of that inhuman tragedy, proceeded from thence through the main street, lengthened by an immense concourse of people so numerous as to be obliged to follow in ranks of 4 and 6 abreast and brought up by a long train of carriages. The sorrow visible in the countenances, together with the peculiar solemnity, surpass description; it was supposed that the spectators and those that followed the corps amounted to 15,000, some supposed 20,000. Note [that] Captain Preston was tried for his life on the affair of the above [on] October 24, 1770. The trial lasted 5 days, but the jury brought him in not guilty.

- 1. The barracks were located at Castle William (renamed Fort Independence in 1797) on Castle Island in Boston Harbor.

- 2. The Old South Church.

- 3. Colonel William Dalrymple (1736–1807), commander of the British troops in Boston.

- 4. John Hancock (1737–1793).

- 5. The fifth fatality, Patrick Carr, died on March 14 and was buried alongside the other victims on March 17

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.