No study questions

No related resources

Introduction

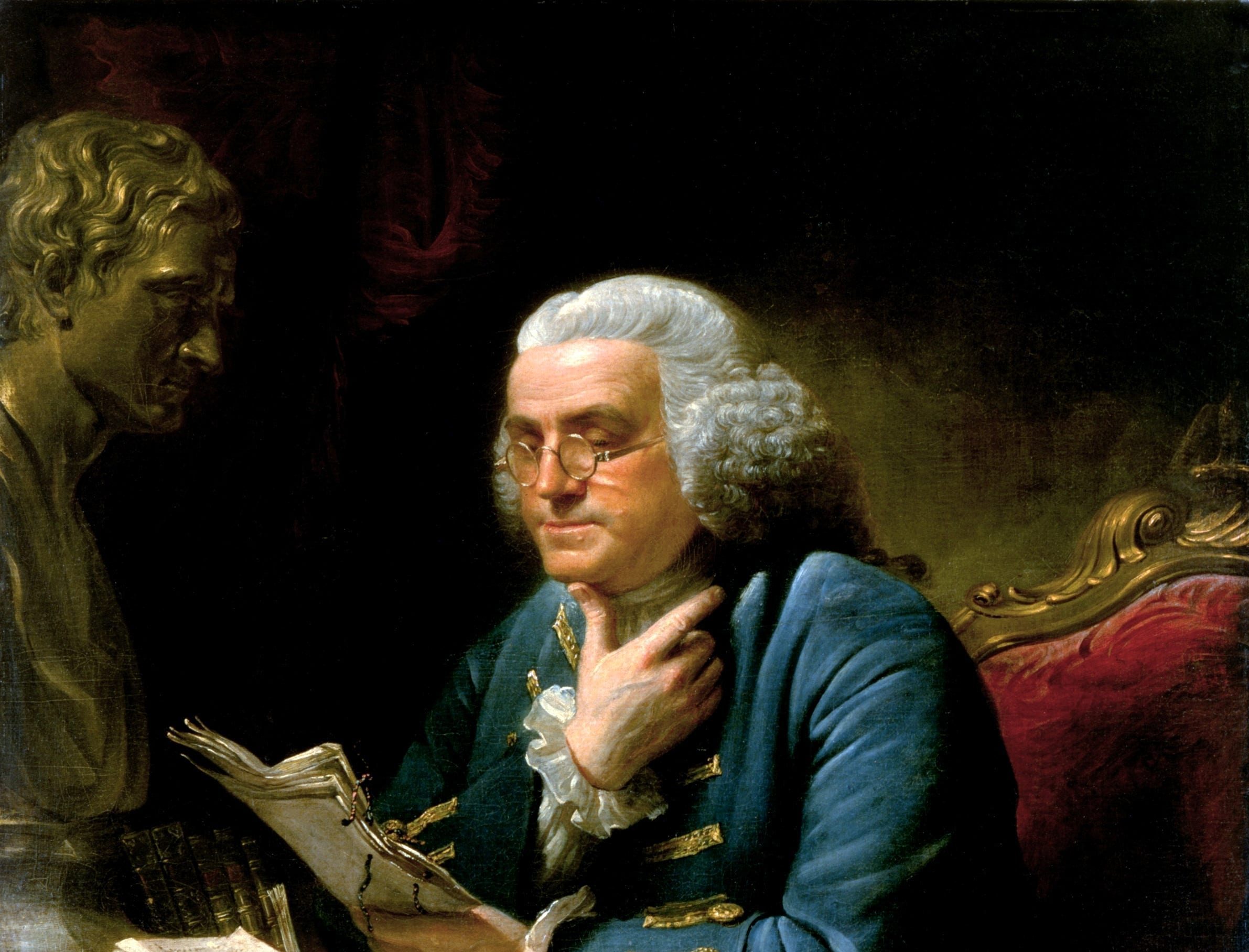

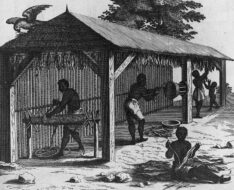

John Locke wrote this piece as part of his role as a commissioner on the Board of Trade of England and the board received it in October 1697 and subsequently rejected it. Locke’s context for the piece is the English Poor Law, an early policy and source for our modern welfare state. The poor laws were a series of acts under Elizabeth I to try and deal with the increasing amount of poor people in Britain as it became more industrialized. The poor law was established in the early seventeenth century when Elizabeth I revised and enforced The Act for Poor Relief of 1597. The original or “old” poor law required each parish to deliver aid to the most deserving in their jurisdiction based on the taxes of the residents of the parish. The poor law arose as a response to the elimination of the feudal system, and the agricultural and industrial revolutions. Workers were no longer tied to a feudal manor with a lord to both provide them with labor and shelter. Workers had to follow the market for labor. After the fall of feudalism, sometimes workers had small farms by which they provided for their families. However, the Enclosure Acts allowed wealthy lords to enclose large pieces of land which drove these small farmers out. These workers then had to go to the city to find work and provided the labor force for the growth of industry. Originally, those who fell through the cracks of the early industrial system were cared for by religious organizations. The poor law was also established to replace the charity that had been previously administered by local monasteries before they were destroyed by the Reformation under the Tudor monarchs. Yet each parish’s ability to administer aid adequately to their own varied. Further, the responsibility of the local parish for its own poor increased with the passing of the 1662 Settlement Act. This new component of the Poor Law reduced labor market mobility because neighboring parishes would not take on new poor to their relief rolls. The administration of the poor laws by parishes meant that they had quite a lot of oversight over who would receive relief. Locke refers to these administrators as overseers and notes how much power they wielded over the lives of the working poor.

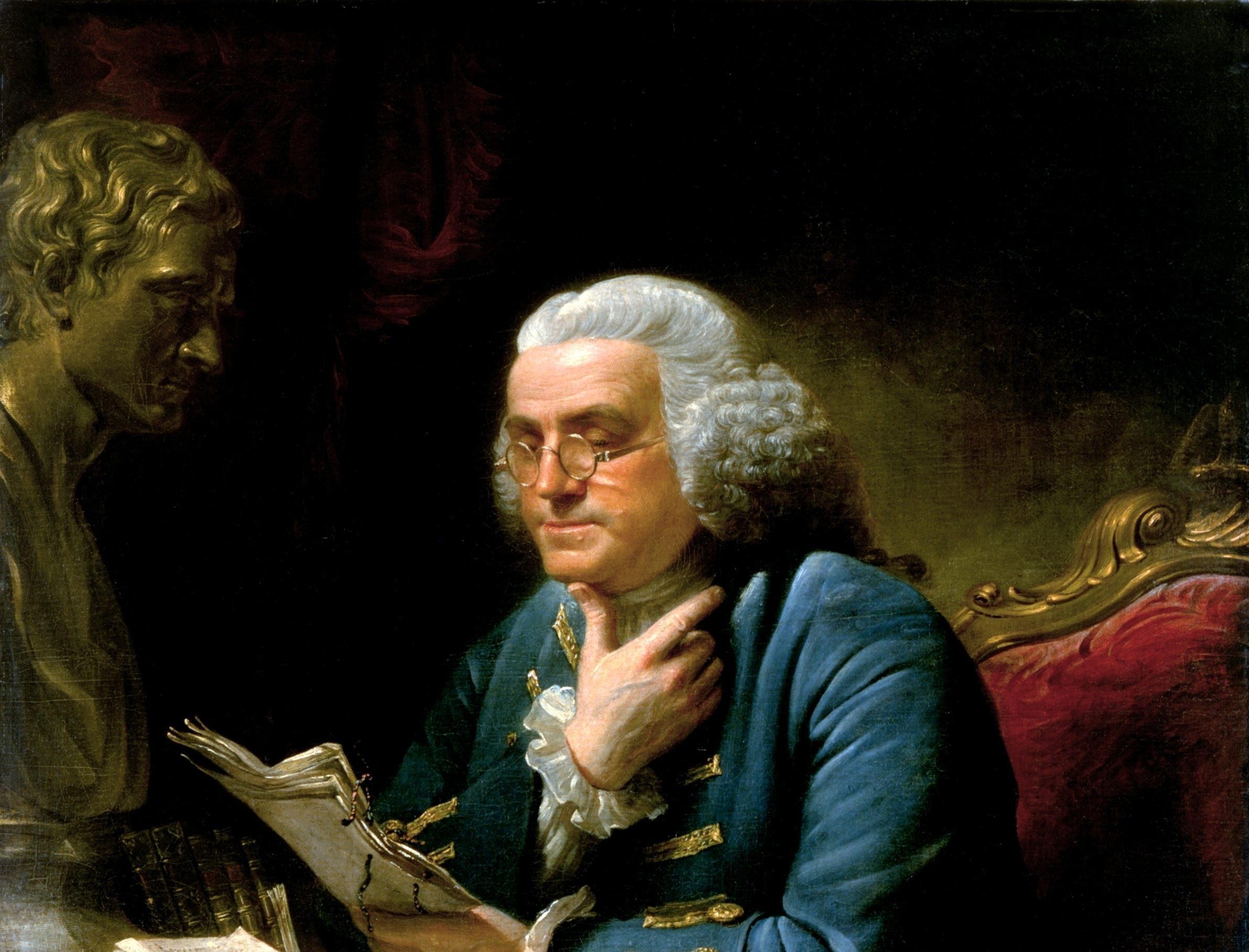

Locke’s premises in the Second Treatise on Government that the dignity of the individual and their value to the community resides in his or her ability to labor inform his policy proposals here. He wrote to his friend, Edward Clarke on February 25, 1698 “It is a matter that requires every Englishman’s best thoughts; for there is not any one thing that I know upon the right regulation whereof the prosperity of his country more depends.”[1] Almost all of his remedies for poverty center on how to get individuals to work.

Source: John Locke, “Draft of a Representation, Containing a Scheme of Methods for the Employment of the Poor” (1697) in Society for the Promotion of Industry in the Southern District of the Parts of Lindsey in the County of Lincoln, and John Locke. An Account of the Origin, Proceedings, And Intentions of the Society for the Promotion of Industry, In the Southern District of the Parts of Lindsey, In the County of Lincoln. The third edition . . . Louth: Printed by R. Sheardown, 1789. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433057644449&view=1up&seq=153 (accessed March 27, 2020).

May it please your excellencies—

His majesty having been pleased, by his commission, to require us particularly to consider of some proper methods for setting on work and employing the poor of this kingdom, and making them useful to the public, and thereby easing others of that burden, and by what ways and means such design may be made most effectual, we humbly beg leave to lay before your excellencies a scheme of such methods as seem unto us most proper for the attainment of those ends.

The multiplying of the poor, and the increase of the tax for their maintenance, is so general an observation and complaint that it cannot be doubted of. . . .

If the cause of this evil be well looked into, we humbly conceive it will be found to have proceeded neither from scarcity of provisions, nor from want of employment for the poor, since the goodness of God has blessed these times with plenty, no less than the former, and a long peace during those reigns gave us as plentiful a trade as ever. The growth of the poor must therefore have some other cause, and it can be nothing else but the relaxation of discipline and corruption of manners; virtue and industry being as constant companions on the one side as vice and idleness are on the other.

The first step, therefore, towards the setting of the poor on work, we humbly conceive, ought to be a restraint of their debauchery by a strict execution of the laws provided against it, more particularly by the suppressing of superfluous brandy shops and unnecessary alehouses, especially in country parishes not lying upon great roads.

Could all the able hands in England be brought to work, the greatest part of the burden that lies upon the industrious for maintaining the poor would immediately cease. For, upon a very moderate computation, it may be concluded that above one half of those who receive relief from the parishes are able to get their livelihood. And all of those who receive such relief from the parishes, we conceive, may be divided into these three sorts.

First, those who can do nothing at all towards their own support. Secondly, those who, though they cannot maintain themselves wholly, yet are able to do something towards it. Thirdly, those who are able to maintain themselves by their own labor. And these last may be again subdivided into two sorts: viz., either those who have numerous families of children whom they cannot or pretend they cannot, support by their labor, or those who pretend they cannot get work, and so live only by begging, or worse.

For the suppression of this last sort of begging drones, who live unnecessarily upon other people’s labor, there are already good and wholesome laws, sufficient for the purpose, if duly executed. We therefore humbly propose that the execution thereof may be at present revived by proclamation, till other remedies can be provided; as also that order be taken every year, at the choosing of churchwardens and overseers of the poor, that the statutes of the 39th EIiz. Cap. IV and the 43rd Eliz. Cap II[2] be read and considered, paragraph by paragraph, and the observation of them, in all their parts, pressed on those who are to be overseers; for we have reason to think that the greatest part of the overseers of the poor, everywhere, are wholly ignorant, and never so much as think that it is the greatest part, or so much as any part, of their duty to set people to work.

But for the more effectual restraining of idle vagabonds, we further humbly propose that a new law may be obtained, by which it be enacted:

[1] That all men sound of limb and mind, above 14 and under 50 years of age, begging in maritime counties out of their own parish without a pass, shall be seized on, either by any officer of the parish where they so beg . . . or by the inhabitants of the house themselves where they beg; and be by them, or any of them, brought before the next justice of the peace or guardian of the poor . . . and, by such justice of the peace or guardian of the poor (after the due and usual correction in the case), be by a pass sent, not to the house of correction (since those houses are now in most counties complained of to be rather places of ease and preferment to the masters thereof than of correction and reformation to those who are sent thither), nor to their places of habitation (since such idle vagabonds usually name some very remote part, whereby the country is put to great charge; and they usually make their escape from the negligent officers before they come thither and so are at liberty for a new ramble). But, if it be in a maritime county, as aforesaid, that they be sent to the next seaport town, there to be kept at hard labor, till some of his majesty’s ships, coming in or near there, give an opportunity of putting them on board, where they shall serve three years under strict discipline, at soldier’s pay (subsistence money being deducted for their victuals on board), and be punished as deserters if they go on shore without leave, or, when sent on shore, if they either go further or stay longer than they have leave.

[2] That all men begging in maritime counties without passes, that are maimed, or above 50 years of age, and all of any age so begging without passes in inland counties nowhere bordering on the sea, shall be sent to the next house of correction, there to be kept at hard labor for three years.

[3] And, to the end that the true use of the houses of correction may not be prevented, as of late it has for the most part been, that the master of each such house shall be obliged to allow unto everyone committed to his charge 4d per diem for their maintenance in and about London. But, in remoter counties, where wages and provisions are much cheaper, there the rate to be settled by the grand jury and judge at the assizes; for which the said master shall have no other consideration nor allowance but what their labor shall produce; whom, therefore, he shall have power to employ according to his discretion, consideration being had of their age and strength.

[4] That the justices of the peace shall, each quarter-sessions, make a narrow inquiry into the state and management of the houses of correction within their district, and take a strict account of the carriage of all who are there, and, if they find that anyone is stubborn, and not at all mended by the discipline of the place, that they order him a longer stay there and severer discipline, that so nobody may be dismissed till he has given manifest proof of amendment, the end for which he was sent thither.

[5] That whoever shall counterfeit a pass shall lose his ears for the forgery the first time that he is found guilty thereof, and the second time, that he shall be transported to the plantations, as in the case of felony.

[6] That whatever female above 14 years old shall be found begging out of her own parish without a pass (if she be an inhabitant of a parish within five miles distance of that she is found begging in) shall be conducted home to her parish by the . . . sworn officer of the parish wherein she was found begging. . . .

[7] That, whenever any such female above 14 years old, within the same distance, commits the same fault a second time, and whenever the same or any such other female is found begging without a lawful pass, the first time, at a greater distance than five miles from the place of her abode, it shall be lawful for any justice of the peace or guardian of the poor, upon complaint made, to send her to the house of correction, there to be employed in hard work three months, and so much longer as shall be to the next quarter-sessions after the determination of the said three months, and that then, after due correction, she have a pass made her by the sessions to carry her home to the place of her abode.

[8] That, if any boy or girl, under 14 years of age, shall be found begging out of the parish where they dwell (if within five miles distance of the said parish), they shall be sent to the next working school, there to be soundly whipped, and kept at work till evening, so that they may be dismissed time enough to get to their place of abode that night. Or, if they live further than five miles off from the place where they are taken begging, that they be sent to the next house of correction, there to remain at work six weeks, and so much longer as till the next sessions after the end of the said six weeks.

These idle vagabonds being thus suppressed, there will not, we suppose, in most country parishes, be many men who will have the pretense that they want work. However, in order to the taking away of that pretense, whenever it happens, we humbly propose that it may be further enacted:

[9] That the guardian of the poor of the parish where any such pretense is made, shall, the next Sunday after complaint made to him, acquaint the parish that such a person complains he wants work, and shall then ask whether anyone is willing to employ him at a lower rate than is usually given, which rate it shall then be in the power of the said guardian to set; for it is not to be supposed that anyone should be refused to be employed by his neighbors, whilst others are set to work, but for some defect in his ability or honesty, for which it is reasonable he should suffer; and he that cannot be set on work for 12d per diem, must be content with 9d or 10d rather than live idly. But, if nobody in the parish voluntarily accepts such a person at the rate proposed by the guardians of the poor, that then it shall be in the power of the said guardian, with the rest of the parish, to make a list of days, according to the proportion of everyone’s tax in the parish to the poor, and that, according to such list, every inhabitant in the same parish shall be obliged, in their turn, to set such unemployed poor men of the same parish on work, at such under-rates as the guardians of the poor shall appoint; and, if any person refuse to set the poor at work in his turn as thus directed, that such person shall be bound to pay them their appointed wages, whether he employ them or no.

[10] That, if any poor man, otherwise unemployed, refuse to work according to such order (if it be in a maritime county), he shall be sent to the next port, and there put on board some of his majesty’s ships, to serve there three years as before proposed; and that what pay shall accrue to him for his service there, above his diet and clothes, be paid to the overseers of the poor of the parish to which he belongs, for the maintenance of his wife and children, if he have any, or else towards the relief of other poor of the same parish; but, if it be not in a maritime county, that every poor man, thus refusing to work, shall be sent to the house of correction.

These methods we humbly propose as proper to be enacted, in order to the employing of the poor who are able, but will not work; which sort, by the punctual execution of such a law, we humbly conceive, may be quickly reduced to a very small number, or quite extirpated.

But the greatest part of the poor maintained by parish rates are not absolutely unable, nor wholly unwilling, to do anything towards the getting of their livelihoods; yet even those, either through want of fit work provided for them, or their unskillfulness in working in what might be a public advantage, do little that turns to any account, but live idly upon the parish allowance, or begging, if not worse. Their labor, therefore, as far as they are able to work, should be saved to the public, and what their earnings come short of a full maintenance should be supplied out of the labor of others, that is, out of the parish allowance.

These are of two sorts:

(i) Grown people, who, being decayed from their full strength, could yet do something for their living, though, under pretense that they cannot get work, they generally do nothing. In the same case with these are most of the wives of day laborers, when they come to have two or three or more children. The looking after their children gives them not liberty to go abroad to seek for work, and so, having no work at home, in the broken intervals of their time they earn nothing; but the aid of the parish is fain to come in to their support, and their labor is wholly lost; which is much loss to the public.

Everyone must have meat, drink, clothing, and firing. So much goes out of the stock of the kingdom, whether they work or no. Supposing, then, there be 100,000 poor in England, that live upon the parish, that is, who are maintained by other people’s labor (for so is everyone who lives upon alms without working), if care were taken that every one of those, by some labor in the woolen or other manufacture, should earn but 1d per diem (which, one with another, they might well do, and more), this would gain to England £130,000 per annum, which, in eight years, would make England above a million of pounds richer.

This, rightly considered, shows us what is the true and proper relief of the poor. It consists in finding work for them, and taking care they do not live like drones upon the labor of others. And, in order to this end, we find the laws made for the relief of the poor were intended; however, by an ignorance of their intention or a neglect of their due execution, they are turned only to the maintenance of people in idleness, without at all examining into the lives, abilities, or industry, of those who seek for relief.

. . .

(ii) Besides the grown people above mentioned, the children of laboring people are an ordinary burden to the parish, and are usually maintained in idleness, so that their labor also is generally lost to the public till they are 12 or 14 years old.

[11] The most effectual remedy for this that we are able to conceive, and which we therefore humbly propose, is that in the forementioned new law to be enacted, it be further provided that working schools be set up in each parish, to which the children of all such as demand relief of the parish, above 3 and under 14 years of age, whilst they live at home with their parents, and are not otherwise employed for their livelihood by the allowance of the overseers of the poor, shall be obliged to come.

By this means the mother will be eased of a great part of her trouble in looking after and providing for them at home, and so be at more liberty to work; the children will be kept in much better order, be better provided for, and from infancy be inured to work, which is of no small consequence to the making of them sober and industrious all their lives after; and the parish will be either eased of this burden, or at least of the misuse in the present management of it. For, a great number of children giving a poor man a title to an allowance from the parish, this allowance is given once a week, or once a month, to the father in money, which he not seldom spends on himself at the alehouse, whilst his children, for whose sake he had it, are left to suffer or perish under the want of necessaries, unless the charity of neighbors relieve them.

We humbly conceive that a man and his wife, in health, may be able by their ordinary labor to maintain themselves and two children. More than two children at one time, under the age of 3 years, will seldom happen in one family. If, therefore, all the children above 3 years old be taken off their hands, those who have never so many, whilst they remain themselves in health, will not need any allowance for them.

We do not suppose that children of 3 years old will be able at that age to get their livelihoods at the working school, but we are sure that what is necessary for their relief will more effectually have that use, if it be distributed to them in bread at that school than if it be given to their fathers in money. What they have at home from their parents is seldom more than bread and water, and that, many of them, very scantily too. If, therefore, care be taken that they have each of them their bellyful of bread daily at school, they will be in no danger of famishing, but, on the contrary, they will be healthier and stronger than those who are bred otherwise. Nor will this practice cost the overseers any trouble; for a baker may be agreed with to furnish and bring into the schoolhouse every day the allowance of bread necessary for all the scholars that are there. And to this may be added, without any trouble, in cold weather, if it be thought needful, a little warm water-gruel; for the same fire that warms the room may be made use of to boil a pot of it.

From this method the children will not only reap the aforementioned advantages with far less charge to the parish than what is now done for them, but they will be also thereby the more obliged to come to school and apply themselves to work, because otherwise they will have no victuals, and also the benefit thereby both to themselves and the parish will daily increase; for, the earnings of their labor at school every day increasing, it may reasonably be concluded that, computing all the earnings of a child from 3 to 14 years of age, the nourishment and teaching of such a child during that whole time will cost the parish nothing; whereas there is no child now which from its birth is maintained by the parish, but, before the age of 14, costs the parish £50 or £60.

Another advantage also of bringing poor children thus to a working school is that by this means they may be obliged to come constantly to church every Sunday, along with their schoolmasters or dames, whereby they may be brought into some sense of religion; whereas ordinarily now, in their idle and loose way of breeding up, they are as utter strangers both to religion and morality as they are to industry.

[12] In order, therefore, to the more effectual carrying on of this work to the advantage of this kingdom, we further humbly propose that these schools be generally for spinning or knitting, or some other part of the woolen manufacture, unless in countries [districts] where the place shall furnish some other materials fitter for the employment of such poor children; in which places the choice of those materials for their employment may be left to the prudence and direction of the guardians of the poor of that hundred; and that the teachers in these schools be paid out of the poor’s rate, as can be agreed.

This, though at first setting up it may cost the parish a little, yet we humbly conceive that (the earnings of the children abating the charge of their maintenance, and as much work being required of each of them as they are reasonably able to perform) it will quickly pay its own charges, with an overplus.

[13] That, where the number of poor children of any parish is greater than for them all to be employed in one school they be there divided into two, and the boys and girls, if thought convenient, taught and kept to work separately.

[14] That the handicraftsmen in each hundred be bound to take every other of their respective apprentices from amongst the boys in some one of the schools in the said hundred, without any money; which boys they may so take at what age they please, to be bound to them till the age of 23 years, that so the length of time may more than make amends for the usual sums that are given to handicraftsmen with such apprentices.

[15] That those also in the hundred who keep in their hands land of their own to the value of £25 per annum or upwards, or who rent £50 per annum or upwards, may choose out of the schools of the said hundred what boy each of them pleases, to be his apprentice in husbandry upon the same condition.

[16] That whatever boys are not by this means bound out apprentices before they are full 14 shall, at the Easter meeting of the guardians of each hundred every year, be bound to such gentlemen, yeomen, or farmers within the said hundred as have the greatest number of acres of land in their hands, who shall be obliged to take them for their apprentices till the age of 23, or bind them out at their own cost to some handicraftsmen; provided always that no such gentleman, yeoman, or farmer shall be bound to have two such apprentices at a time.

[17] That grown people also (to take away their pretense of want of work) may come to the said working schools to learn, where work shall accordingly be provided for them.

[18] That the materials to be employed in these schools, and among other the poor people of the parish, be provided by a common stock in each hundred, to be raised out of a certain portion of the poor’s rate of each parish as requisite; which stock, we humbly conceive, need be raised but once; for, if rightly managed, it will increase.

[19] That some person, experienced and well skilled in the particular manufacture which shall be judged fittest to set the poor of each hundred on work, be appointed storekeeper for that hundred, who shall, accordingly, buy in the wool or other materials necessary; that this storekeeper be chosen by the guardians of the poor of each hundred, and be under their direction, and have such salary as they shall appoint to be paid pro rata upon the pound, out of the poor’s tax of every parish; and, over and above which salary, that he also have 2s in the pound yearly for every 20s that shall be lessened in the poor’s tax of any parish, from the first year of his management.

. . .

[24] That the guardians of the poor of each respective hundred shall meet every year in Easter week, in the place where the stores of that hundred are kept, to take an account of the stock; and as often, also, at other times as shall be necessary to inspect the management of it and to give directions therein, and in all other things relating to the poor of the hundred.

[25] That no person in any parish shall be admitted to an allowance from the parish but by the joint consent of the guardian of the said parish and the vestry.

[26] That the said guardian also, each of them, within the hundred whereof he is guardian, have the power of a justice of the peace over vagabonds and beggars, to make them passes, to send them to the seaport towns, or houses of correction, as before proposed. [Locke also notes that the guardians will control the working schools and all funds raised to administer the poor].

These foregoing rules and methods being what we humbly conceive most proper to be put in practice for the employment and relief of the poor generally throughout the country, we now further humbly propose for the better and more easy attainment of the same end in cities and towns corporate, that it may be enacted.

[27] That in all cities and towns corporate the poor’s tax be not levied by distinct parishes, but by one equal tax throughout the whole corporation.

. . .

[38] And, since the behavior and wants of the poor are best known amongst their neighbors, and that they may have liberty to declare their wants, and receive broken bread and meat, or other charity, from well-disposed people, that it be therefore permitted to those whose names are entered in the poor’s book, and who wear the badges required, to ask and receive alms in their respective parishes at certain hours of the day to be appointed by the guardians; but, if any of these are taken begging at any other hour than those allowed, or out of their respective parishes, though within the same corporation, they shall be sent immediately, if they are under 14 years of age, to the working school to be whipped, and, if they are above 14, to the house of correction, to remain there six weeks and so much longer as till the next quarter-sessions after the said six weeks are expired.

[39] That, if any person die for want of due relief in any parish in which he ought to be relieved, the said parish be fined according to the circumstances of the fact and the heinousness of the crime.

[40] That every master of the king’s ships shall be bound to receive without money, once every year (if offered him by the magistrate or other officer of any place within the bounds of the port where his ship shall be), one boy, sound of limb, above 13 years of age, who shall be his apprentice for nine years.

An act concerning Servants and Slaves

October 31, 1705

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.