No study questions

No related resources

The Governor’s Speech

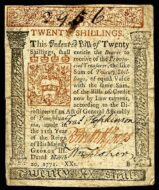

…When our predecessors first took possession of this plantation, or colony, under a grant and charter from the Crown of England, it was their sense, and it was the sense of the kingdom, that they were to remain subject to the supreme authority of Parliament. This appears from the charter itself, and from other irresistible evidence. This supreme authority has from time to time, been exercised by Parliament, and submitted to by the colony, and hath been, in the most express terms, acknowledged by the Legislature, and, except about the time of the anarchy and confusion in England, which preceded the restoration of King Charles the Second, I have not discovered that it has been called in question, even by private or particular persons, until within seven or eight years last past. Our provincial or local laws have, in numerous instances, had relation to acts of Parliament, made to respect the plantations in general, and this colony in particular, and in our Executive Courts, both Juries and Judges have, to all intents and purposes, considered such acts as part of our rule of law. Such a constitution, in a plantation, is not peculiar to England, but agrees with the principles of the most celebrated writers upon the law of nations, that “when a nation takes possession of a distant country, and settles there, that country, though separated from the principal establishment, or mother country, naturally becomes a part of the state, equally with its ancient possessions.”

So much, however, of the spirit of liberty breathes through all parts of the English constitution, that, although from the nature of government, there must be one supreme authority over the whole, yet this constitution will admit of subordinate powers with Legislative and Executive authority, greater or less, according to local and other circumstances. Thus we see a variety of corporations formed within the kingdom, with powers to make and execute such by-laws as are for their immediate use and benefit, the members of such corporations still remaining subject to the general laws of the kingdom. We see also governments established in the plantations, which, from their separate and remote situation, require more general and extensive powers of legislation within themselves, than those formed within the kingdom, but subject, nevertheless, to all such laws of the kingdom as immediately respect them, or are designed to extend to them; and, accordingly, we, in this province have, from the first settlement of it, been left to the exercise of our Legislative and Executive powers, Parliament occasionally, though rarely, interposing, as in its wisdom has been judged necessary.;

Under this constitution, for more than one hundred years, the laws both of the supreme and subordinate authority were in general, duly executed; offenders against them have been brought to condign punishment, peace, and order have been maintained, and the people of this province have experienced as largely the advantages of government, as, perhaps, any people upon the globe; and they have, from time to time, in the most public manner expressed their sense of it, and, once in every year, have offered up their united thanksgivings to God for the enjoyment of these privileges, and, as often, their united prayers for the continuance of them.

At length the constitution has been called in question, and the authority of the Parliament of Gret Britain to make and establish laws for the inhabitants of this province has been, by many, denied. What was at first whispered with caution, was soon after openly asserted in print; and, of late, a number of inhabitants, in several of the principal towns in the province, having assembled together in their respective towns, and have assumed the name of legal town meetings, have passed resolves, which they have ordered to be placed upon their own records, and caused to be printed and published in pamphlets and newspapers. I am sorry that it is thus become impossible to conceal, what I could wish had never been made public. I will not particularize these resolves or votes, and shall only observe to you in general, that some of them deny the supreme authority of Parliament, and so are repugnant to the principles of the constitution, and that others speak of this supreme authority, of which the King is a constituent part, and to every act of which his assent is necessary, in such terms as have a direct tendency to alienate the affections of the people from their Sovereign, who has ever been most tender of their rights, and whose person, crown, and dignity, we are under every possible obligation to defend and support. In consequence of these resolves, committees of correspondence are formed in several of those towns, to maintain the principles upon which they are founded.

I know of no arguments, founded in reason, which will be sufficient to support these principles, or to justify the measures taken in consequence of them. It has been urged, that the sole power of making laws is granted, by charter, to a Legislature established in the province, consisting of the King, by his Representative the Governor, the Council, and the House of Representatives; that, by this charter, there are likewise granted, or assured to the inhabitants of the province, all the liberties and immunities of free and natural subjects, to all intents, constructions and purposes whatsoever, as if they had been born within the realms of England; that it is part of the liberties of English subjects, which has its foundation in nature, to be governed by laws made by their consent in person, or by their representative; that the subjects in this province are not, and cannot be represented in the Parliament of Great Britain, and, consequently, the acts of that Parliament cannot be binding upon them.

I do not find, gentlemen, in the charter, such an expression as sole power, or any words which import it. The General Court has, by charter, full power to make such laws, as are not repugnant to the laws of England. A favorable construction has been put upon this clause, when it has been allowed to intend such laws of England only, as are expressly declared to respect us. Surely then this is, by charter, a reserve of power and authority to Parliament to bind us by such laws, at least, as are made expressly to refer to us, and consequently, is a limitation of the power given to the General Court. Nor can it be contended, that, by the limits of free and natural subjects, is to be understood an exemption from acts of Parliament, because not represented there, seeing it is provided by the same charter, that such acts shall be in force; and if they that make the objection to such acts, will read the charter with attention, they must be convinced that this grant of liberties and immunities is nothing more than a declaration and assurance on the part of the Crown, that the place, to which their predecessors were about to remove, was, and would be considered as part of the dominions of the Crown of England, and, therefore, that the subjects of the Crown so removing, and those born there, or in their passage thither, or in their passage from thence, would not become aliens, but would, throughout all parts of the English dominions, wherever they might happen to be, as well as within the colony, retain the liberties and immunities of free and natural subjects, their removal from, or not being born within the realm notwithstanding. If the plantations be part of the dominions of the Crown, this clause in the charter does not confer or reserve any liberties, but what would have been enjoyed without it, and what the inhabitants of every other colony do enjoy where they are without a charter. If the plantations are not the dominions of the Crown, will not all that are born here, be considered as born out of the liegeance of the King of England, and, whenever they go into any parts of the dominions, will they not be deemed aliens to all intents and purposes, this grant in the charter notwithstanding?

They who claim exemption from acts of Parliament by virtue of their rights as Englishmen, should consider that it is impossible the rights of English subjects should be the same, in every respect, in all parts of the dominions. It is one of their rights as English subjects, to be governed by laws made by persons, in whose election they have, from time to time, a voice; they remove from the kingdom, where, perhaps, they were in the full exercise of this rights, to the plantations, where it cannot be exercised, or where the exercise of it would be of no benefit to them. Does it follow that the government, by their removal from one part of the dominions to another, loses its authority over that part to which they remove, and that they are freed from the subjection they were under before; or do they expect that government should relinquish its authority because they cannot enjoy this particular right? Will it not rather be said that by this their voluntary removal, they have relinquished for a time at least, one of the rights of an English subject, which they might, if they pleased, have continued to enjoy, and may again enjoy, whensoever they will return to the place where it can be exercised?

They who claim exemption, as part of their rights by nature, should consider that every restraint which men are laid under by a state of government, is a privation of part of their natural rights; and of all the different forms of government which exist, there can be no two of them in which the departure from natural rights is exactly the same. Even in case of representation by election, do they not give up part of their natural rights when they consent to be represented by such person as shall b e chosen by the majority of the electors, although their own voices may be for some other person? And is it not contrary to their natural rights to be obliged to submit to a representative for seven years, or even one year, after they are dissatisfied with his conduct, although they gave their voices for him when he was elected? This must, therefore, be considered as an obligation against a state of government, rather than against any particular form.

If what I have said shall not be sufficient to satisfy such as object to the supreme authority of Parliament over the plantations, there may something further be added to induce them to an acknowledgment of it, which, I think, will well deserve their consideration. I know of no line that can be drawn between the supreme authority of Parliament and the total independence of the colonies: it is impossible there should be two independent Legislatures in one and the same state; for, although there may be but one head, the King, yet the two Legislative bodies will make two governments as distinct as the kingdoms of England and Scotland before the union…

Answer of the House of Representatives

We fully agree with your Excellency, that our own happiness, as well as his Majesty’s service, very much depends upon peace and order; and we shall at all times take such measures as are consistent with our constitution, and the rights of the people, to promote and maintain them. That the government at present is in a very disturbed state, is apparent. But we cannot ascribe it to the people’s having adopted unconstitutional principles, which seems to be the cause assigned for it by your Excellency. It appears to us, to have been occasioned rather by the British House of Commons assuming and exercising a power inconsistent with the freedom of the constitution, to give and grant the property of the colonists, and appropriate the same without their consent…

You are pleased to say that, “when our predecessors first took possession of this plantation, or colony, under a grant and charter from the Crown of England, it was their sense, and it was the sense of the kingdom, that they were to remain subject to the supreme authority of Parliament;” whereby we understand your Excellency to mean, in the sense of the declaratory act of Parliament…in all cases whatever. And, indeed, it is difficult, if possible, to draw a line of distinction between the universal authority of Parliament over the colonies, and no authority at all. It is, therefore, necessary for us to inquire how it appears, for your Excellency has not shown it to us, that when, or at the time that our predecessors took possession of this plantation, or colony, under a grant and charter from the Crown of England, it was their sense, and the sense of the kingdom, that they were to remain subject to the authority of Parliament. In making this inquiry, we shall, according to your Excellency’s recommendation, treat the subject with calmness and candor, and also with a due regard to truth…

The King, in the first charter to this colony, expressly grants, that it “shall be construed, reputed, and adjudged in all cases, most favorably on the behalf and for the benefit and behoof of the said Governor and Company, and their successors- any matter, cause or thing, whatsoever, to the contrary notwithstanding.” It is one of the liberties of free and natural subjects, born and abiding within the realm, to be governed, as your Excellency observes, “by laws made by persons, in whose elections they, from time to time, have a voice.” This is an essential right. For nothing is more evident, than, that any people, who are subject to the unlimited power of another, must be in a state of abject slavery. It was easily and plainly foreseen, that the right of representation in the English Parliament, could not be exercised by the people of this colony. It would be impracticable, if consistent with the English constitution. And for this reason, that this colony might have and enjoy all the liberties and immunities of free and natural subjects within the realm, as stipulated in the charter, it was necessary, and a Legislative was accordingly constituted within the colony; one branch of which, consists of Representatives chosen by the people, to make all laws, statutes, ordinances, &c. for the well ordering and governing the same, not repugnant to the laws of England, or, as nearly as conveniently might be, agreeable to the fundamental laws of the English constitution. We are, therefore, still at a loss to conceive, where your Excellency finds it ’provided in the same charter, that such acts,” viz. acts of Parliament, made expressly to refer to us, “shall be in force” in this province. There is nothing to this purpose, expressed in the charter, or in our opinion, even implied in it. And surely it would be very absurd, that a charter, which is evidently formed upon a supposition and intention, that a colony is and should be considered as not within the realm; and declared by the very Prince who granted it, to be not within the jurisdiction of Parliament, should yet provide, that the laws which the same Parliament should make, expressly to refer to that colony, should be in force therein. Your Excellency is pleased to ask, “does it follow, that the government, by their (our ancestors) removal from one part of the dominions to another, loses its authority over that part to which they remove; and that they are freed from the subjection they were under before?” We answer, if that part of the King’s dominions, to which they removed, was not then a part of the realm, and was never annexed to it, the Parliament lost no authority over it, having never had such authority; and the emigrations were consequently freed from the subjection they were under before their removal. The power and authority of Parliament, being constitutionally confined within the limits of the realm, and the nation collectively, of which alone it is the representing and Legislative Assembly. Your Excellency further asks, “will it not rather be said, that by this, their voluntary removal, they have relinquished, for a time, at least, one of the rights of an English subject, which they might, if they pleased, have continued to enjoy, and may again enjoy, whenever they return to the place where it can be exercised?” To which we answer; they never did relinquish the right to be governed by laws, made by persons in whose election they had a voice. The King stipulated with them, that they should have and enjoy all the liberties of free and natural subjects, born within the realm, to all intents, purposes and constructions, whatsoever; that is, that they should be as free as those, who were to abide within the realm: consequently, he stipulated with them, that they should enjoy and exercise this most essential right, which discriminates freemen from vassals, uninterruptedly, in its full sense and meaning; and they did, and ought still to exercise it, without the necessity of returning, for the sake of exercising it, to the nation or state of England…

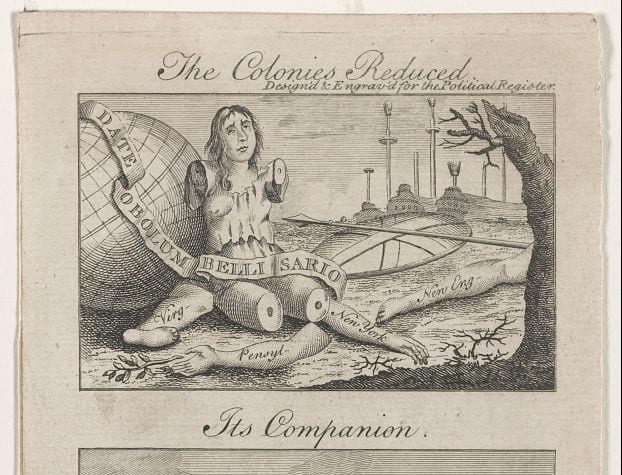

Your Excellency tell us, “you know of no line that can be drawn between the supreme authority of Parliament and the total independence of the colonies.” If there be no such line, the consequence is, either that the colonies are the vassals of the Parliament, or that they are totally independent. As it cannot be supposed to have been the intention of the parties in the compact, that we should be reduced to a state of vassalage, the conclusion is, that it was their sense, that we were thus independent. “It is impossible,” your Excellency says, “that there should be two independent Legislatures in one and the same state.” May we not then further conclude, that it was their sense, that the colonies were, by their charters, made distinct states from the mother country? Your Excellency adds “for although there may by but one head, the King, yet the two Legislative bodies will make two governments as distinct as the kingdoms of England and Scotland, before the union.” Very true, may it please your Excellency; and if they interfere not with each other, what hinders, but that being united in one head and common Sovereign, they may live happily in that connection, and mutually support and protect each other? Notwithstanding all the terrors which your Excellency has pictured to us as the effects of a total independence, there is more reason to dread the consequences of absolute uncontrolled power, whether of a nation or a monarch, than those of a total independence. It would be a misfortune “to know by experience, the difference between the liberties of an English colonist and those of the Spanish, French, and Dutch:” and since the British Parliament has passed an act, which is executed even with rigor, though not voluntarily submitted to, for raising a revenue, and appropriating the same, without the consent of the people who pay it, and have claimed a power of making such laws as they please, to order and govern us, your Excellency will excuse us in asking, whether you do not think we already experience too much of such a difference, and have not reason to fear we shall soon be reduced to a worse situation than that of the colonies of France, Spain, or Holland?…

After all that we have said, we would be far from being understood to have in the least abated that just sense of allegiance which we owe to the King of Great Britain, our rightful Sovereign; and should the people of this province be left to the free and full exercise of all the liberties and immunities granted to them by charter, there would be no danger of an independence on the Crown. Our charters reserve great power to the Crown in its Representative, fully sufficient to balance, analogous to the English constitution, all the liberties and privileges granted to the people. All this your Excellency knows full well; and whoever considers the power and influence, in all their branches, reserved by our charter, to the Crown, will be far from thinking that the Commons of this province are too independent.

Virginia Resolves of 1773

March 12, 1773

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.