Introduction

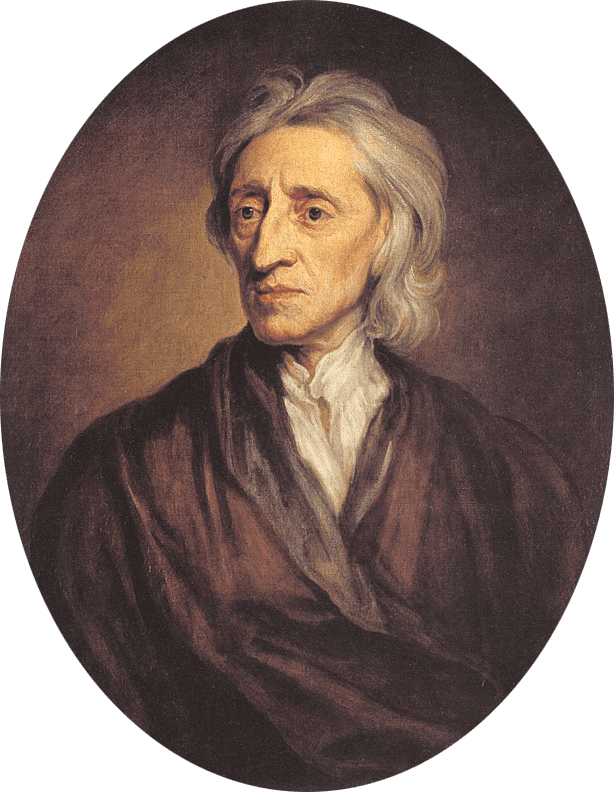

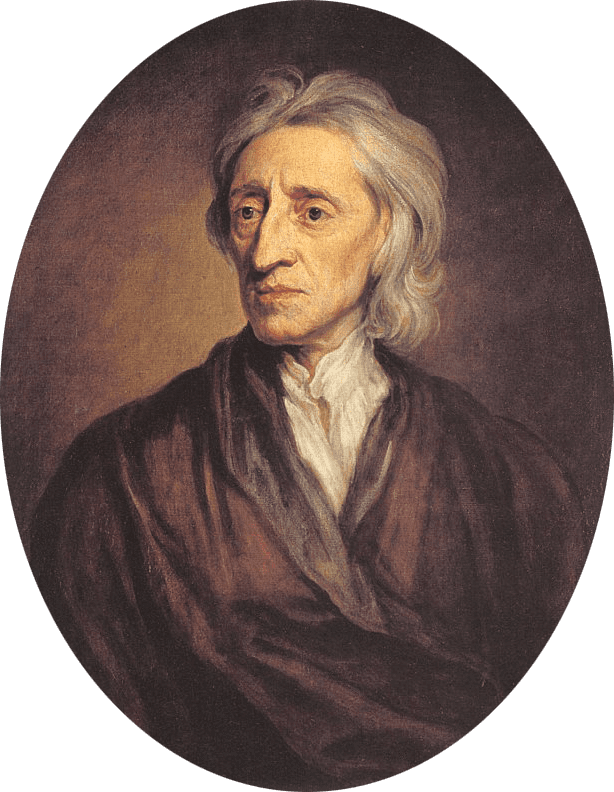

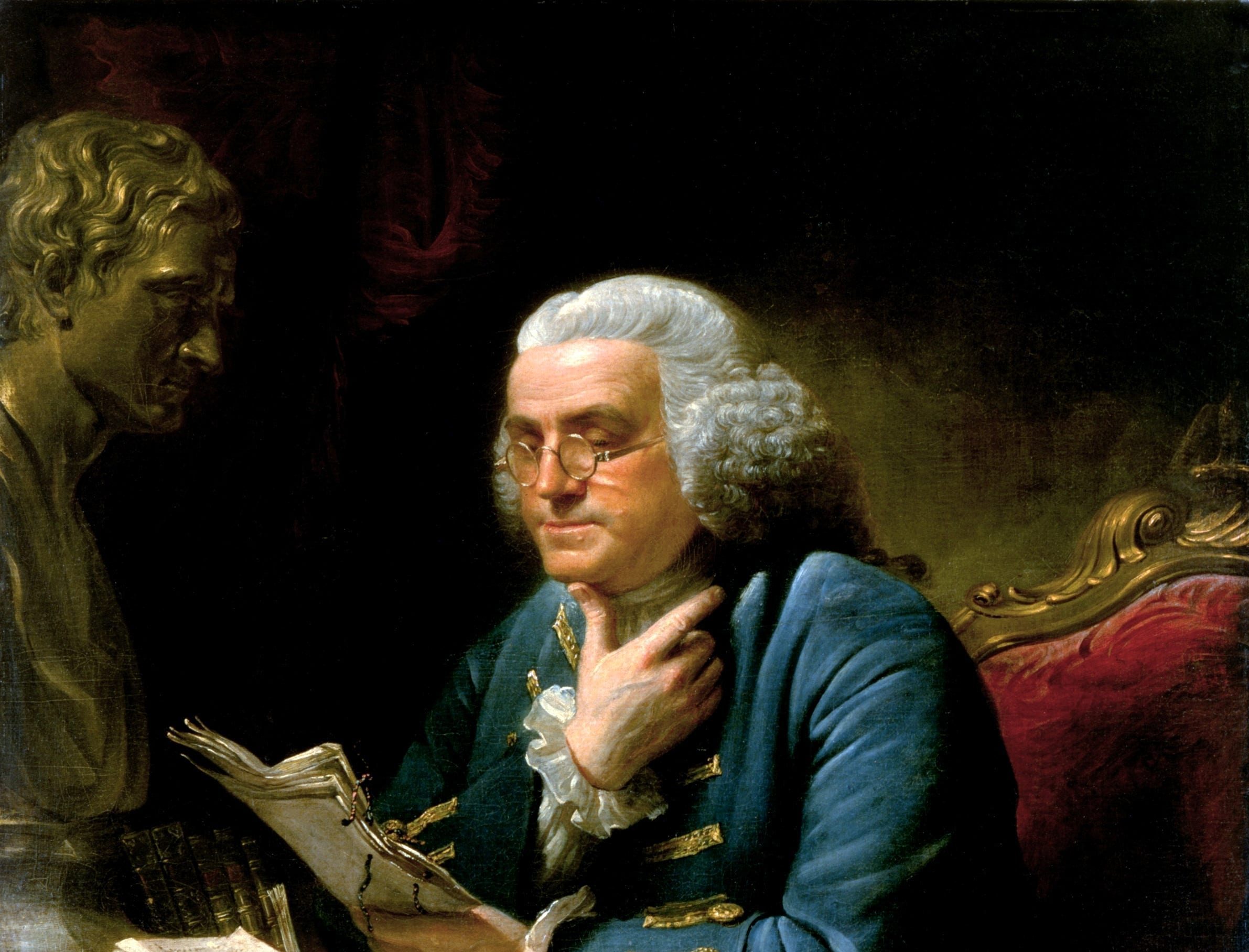

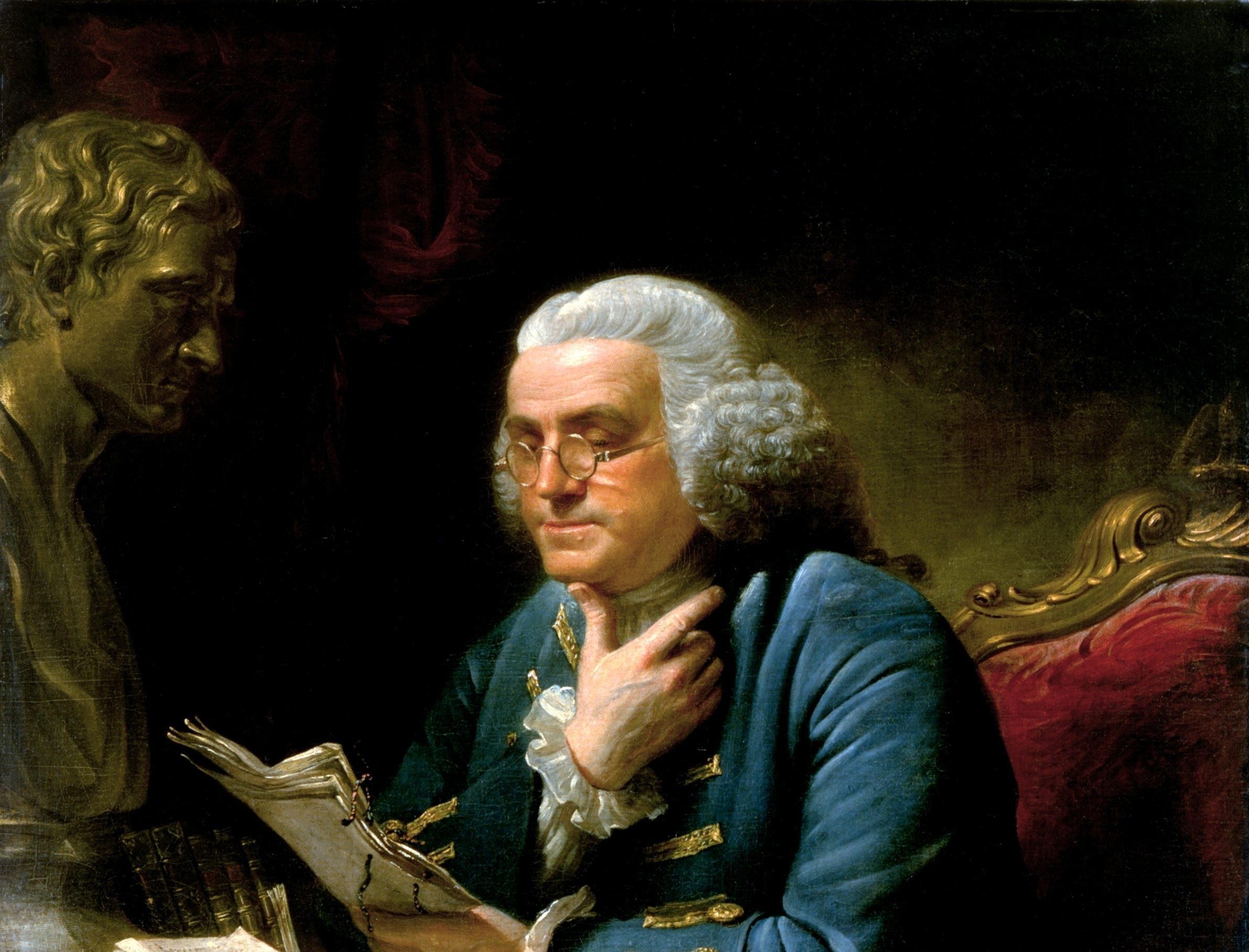

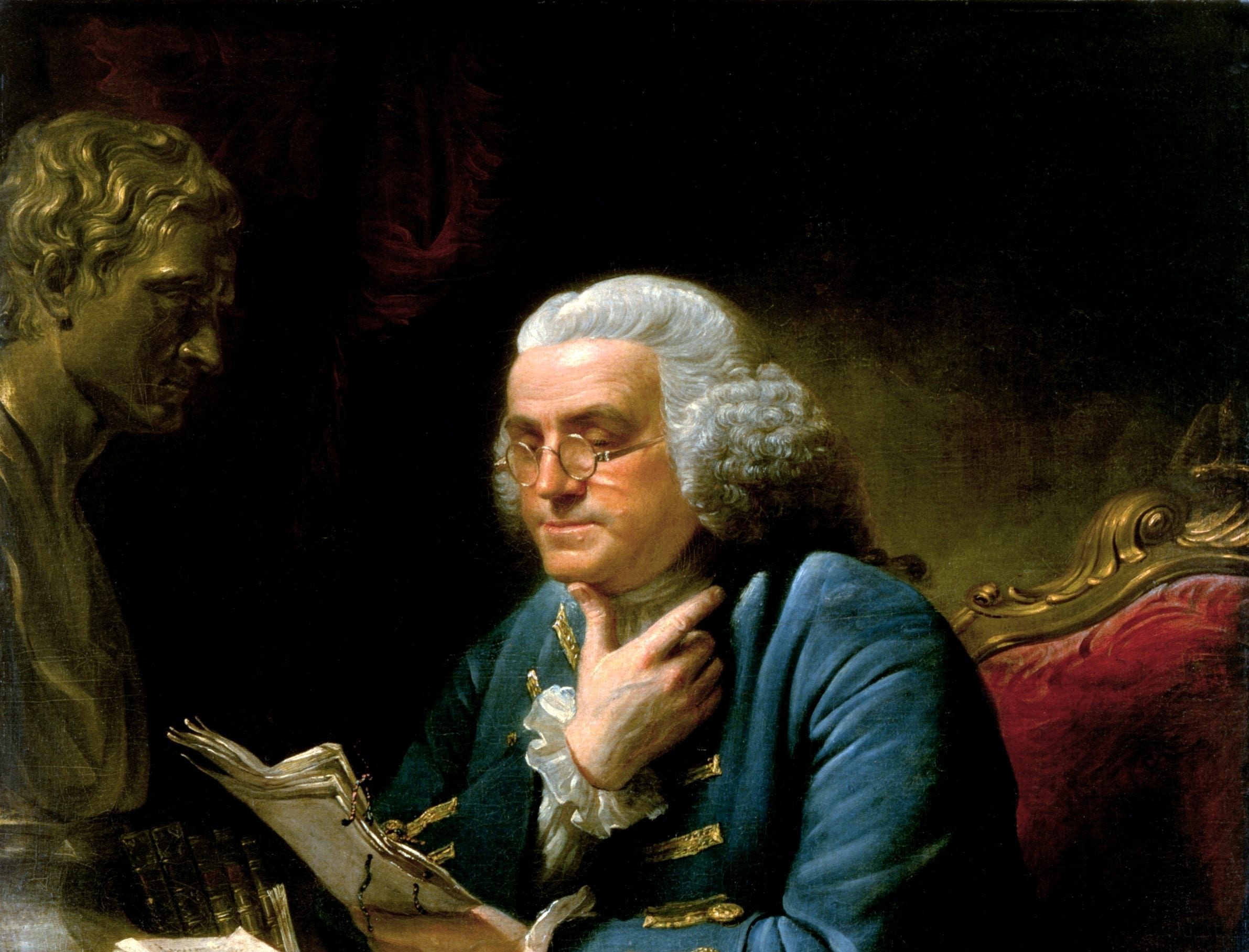

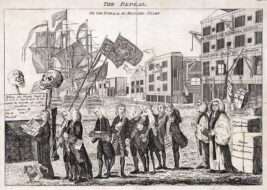

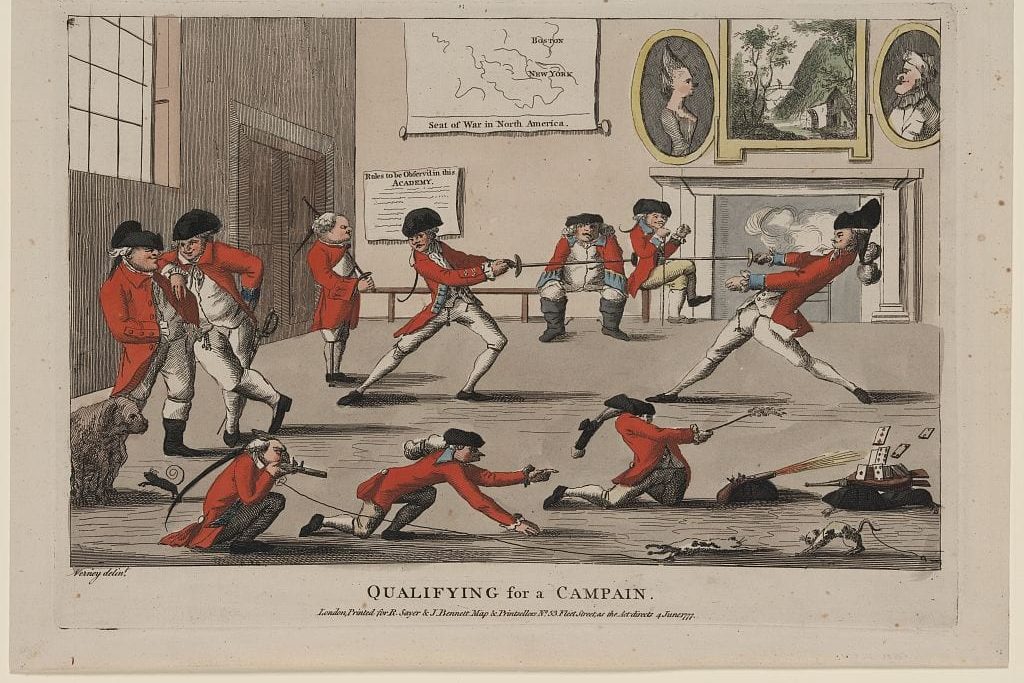

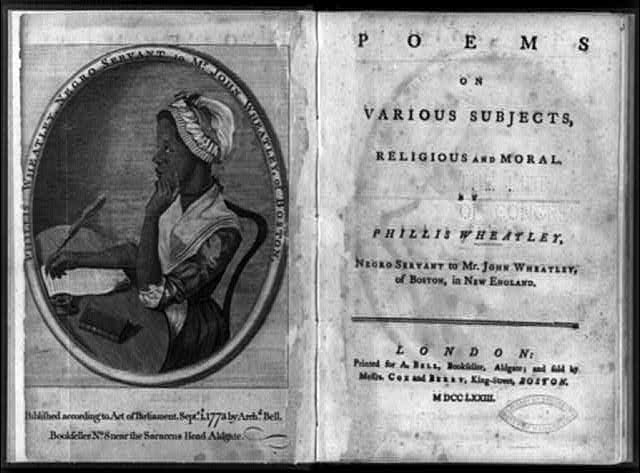

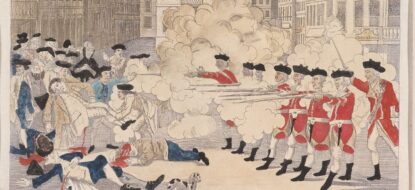

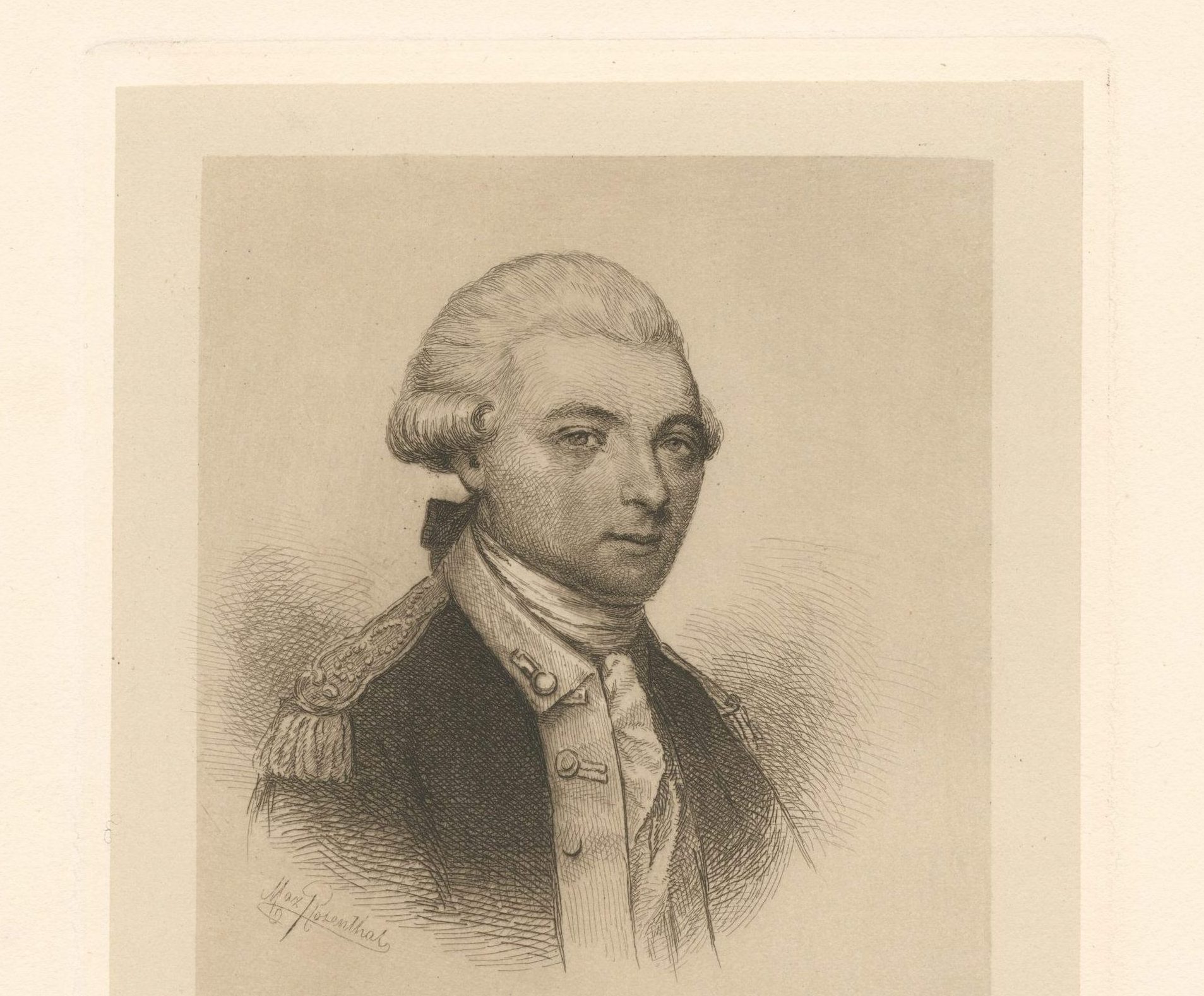

Founding father and second president of the United States John Adams (1735–1826) started his career practicing law in Massachusetts. He was an opponent of the Stamp Act (1765), but he agreed to defend the British soldiers accused of murder after they opened fire on a crowd in what came to be known as the Boston Massacre (1770). He rose to fame for his successful defense of the soldiers. He later became an ardent patriot and a leader of the revolutionary struggle.

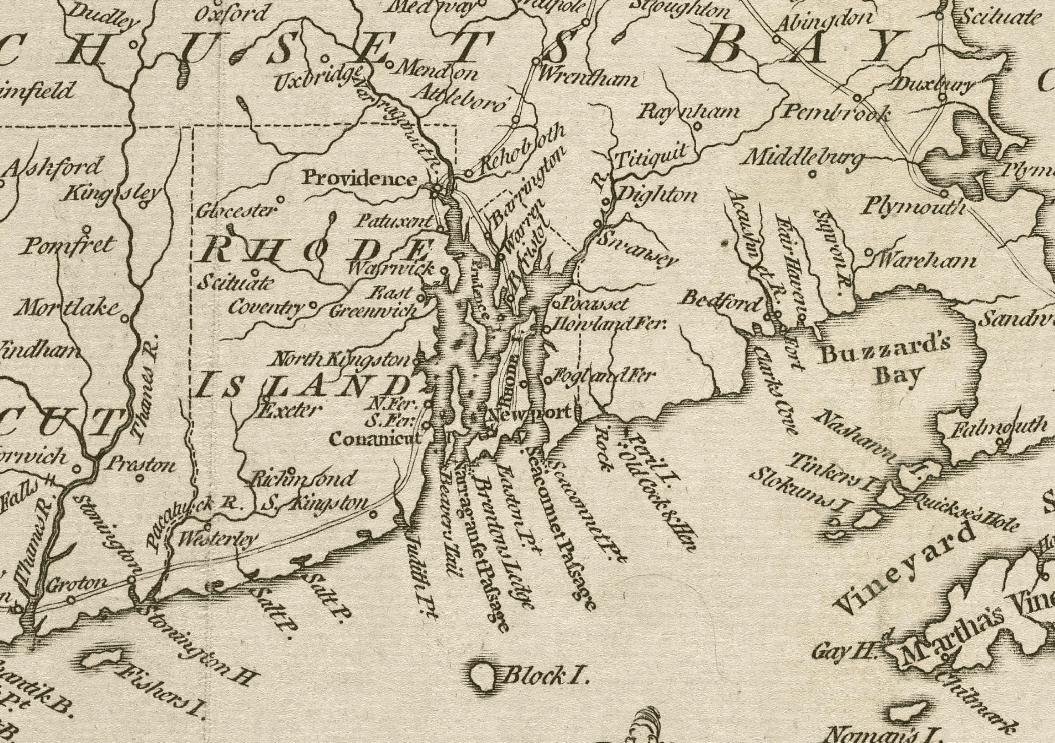

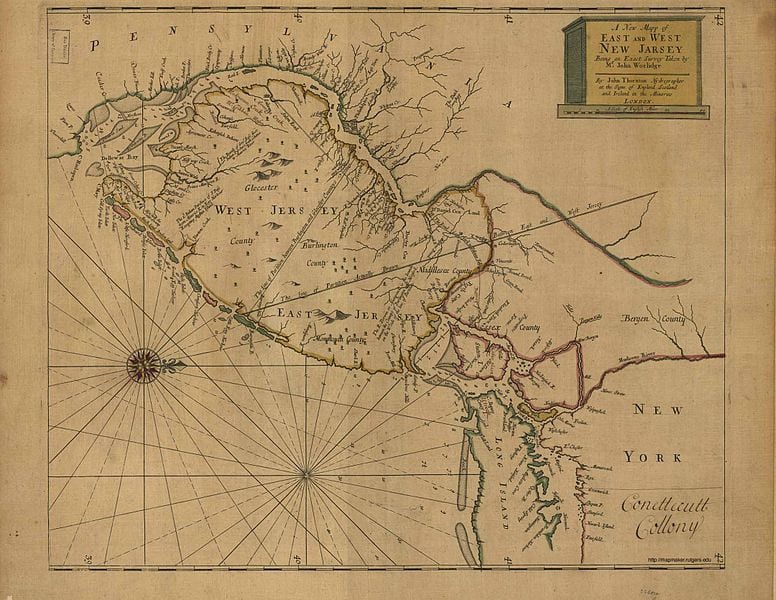

In this document, written as the colonies were writing their first state constitutions in 1776, Adams outlined his understanding of the basic principles of government, including the separation of powers. His argument influenced the constitutions of several states, including North Carolina, Virginia, and Adams’ own home state of Massachusetts. Written a few short months before the Declaration of Independence and several years before the Constitution was ratified, Adams’ account illustrates that the separation of powers doctrine had already taken root in the colonies before 1787.

Adams described the danger of having the executive, legislative, and judicial power housed in one assembly and instead suggested separating these powers in different branches, with each thereby able to check the others. He also described the importance of separating the legislative power into separate chambers.

—J. David Alvis and Joseph Postell

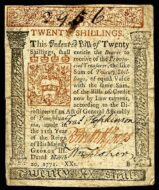

John Adams, Thoughts on Government: Applicable to the Present State of the American Colonies: in a Letter from a Gentleman to His Friend (Philadelphia: John Dunlap, 1776), 193–199. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/3q75

. . . We ought to consider, what is the end of government, before we determine which is the best form. Upon this point all speculative politicians will agree, that the happiness of society is the end of government. . . . From this principle it will follow, that the form of government, which communicates ease, comfort, security, or in one word happiness to the greatest number of persons, and in the greatest degree, is the best. . . .

As good government is an empire of laws, how shall your laws be made? In a large society, inhabiting an extensive country, it is impossible that the whole should assemble, to make laws. The first necessary step, then, is to depute power from the many, to a few of the most wise and good. But by what rules shall you choose your representatives? Agree upon the number and qualifications of persons, who shall have the benefit of choosing, or annex this privilege to the inhabitants of a certain extent of ground.

The principal difficulty lies, and the greatest care should be employed in constituting this representative assembly. It should be in miniature, an exact portrait of the people at large. It should think, feel, reason, and act like them. That it may be the interest of this assembly to do strict justice at all times, it should be an equal representation, or in other words equal interest among the people should have equal interest in it. . . .

A representation of the people in one assembly being obtained, a question arises whether all the powers of government, legislative, executive, and judicial, shall be left in this body? I think a people cannot be long free, nor ever happy, whose government is in one assembly. My reasons for this opinion are as follow.

- A single assembly is liable to all the vices, follies, and frailties of an individual. Subject to fits of humor, starts of passion, flights of enthusiasm, partialities of prejudice, and consequently productive of hasty results and absurd judgments: And all these errors ought to be corrected and defects supplied by some controlling power.

- A single assembly is apt to be avaricious, and in time will not scruple to exempt itself from burdens which it will lay, without compunction, on its constituents.

- A single assembly is apt to grow ambitious, and after a time will not hesitate to vote itself perpetual. This was one fault of the long parliament, but more remarkably of Holland, whose Assembly first voted themselves from annual to septennial, then for life, and after a course of years, that all vacancies happening by death, or otherwise, should be filled by themselves, without any application to constituents at all.

- A representative assembly, although extremely well qualified, and absolutely necessary as a branch of the legislature, is unfit to exercise the executive power, for want of two essential properties, secrecy and dispatch.

- A representative assembly is still less qualified for the judicial power; because it is too numerous, too slow, and too little skilled in the laws.

- Because a single assembly, possessed of all the powers of government, would make arbitrary laws for their own interest, execute all laws arbitrarily for their own interest, and adjudge all controversies in their own favor.

But shall the whole power of legislation rest in one assembly? Most of the foregoing reasons apply equally to prove that the legislative power ought to be more complex—to which we may add, that if the legislative power is wholly in one assembly, and the executive in another, or in a single person, these two powers will oppose and enervate upon each other, until the contest shall end in war, and the whole power, legislative and executive, be usurped by the strongest.

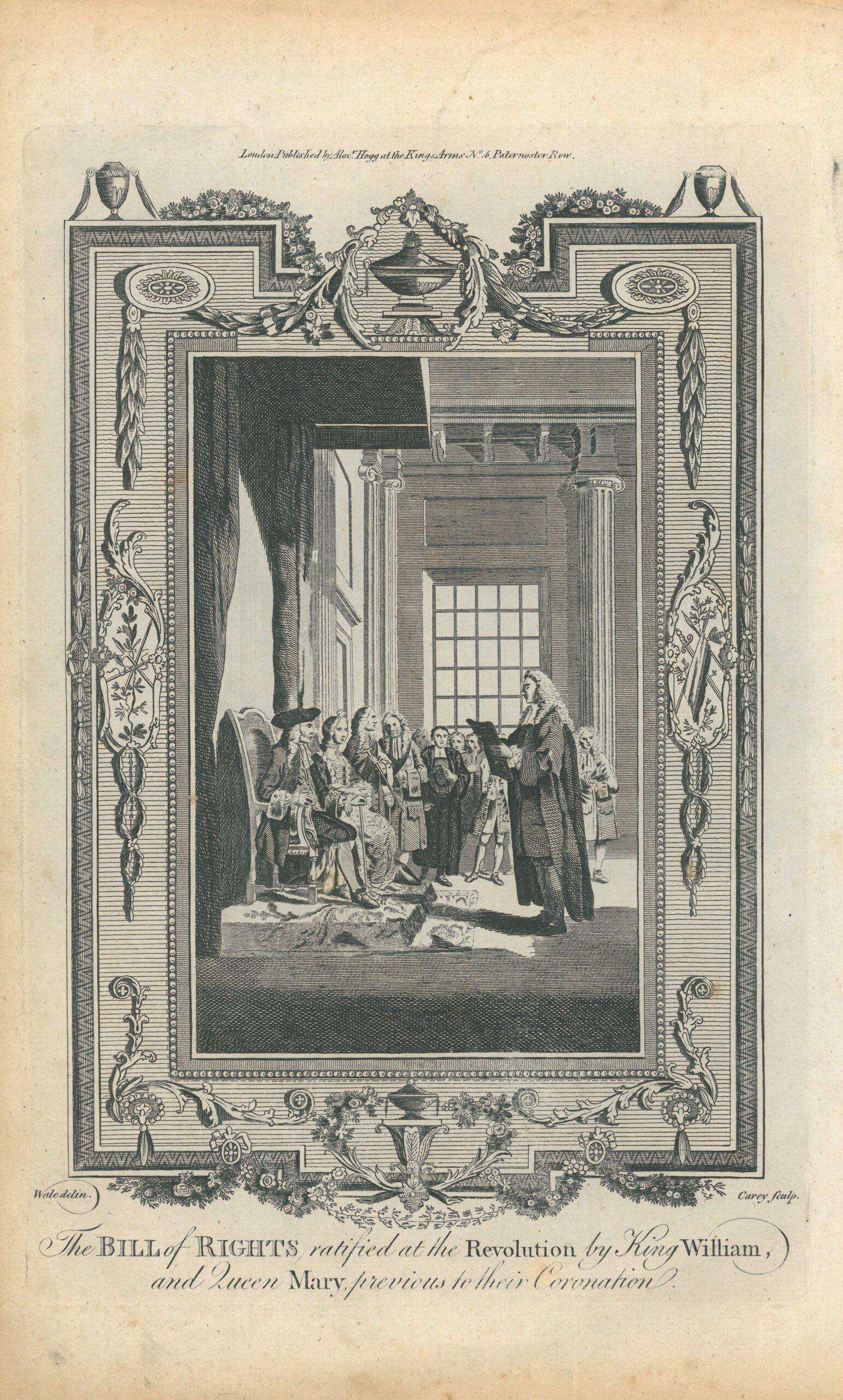

The judicial power, in such case, could not mediate, or hold the balance between the two contending powers, because the legislative would undermine it. And this shows the necessity too, of giving the executive power a negative upon the legislative, otherwise this will be continually encroaching upon that.

To avoid these dangers let a distinct assembly be constituted, as a mediator between the two extreme branches of the legislature, that which represents the people and that which is vested with the executive power.

Let the representative assembly then elect by ballot, from among themselves or their constituents, or both, a distinct assembly, which for the sake of perspicuity we will call a council. It may consist of any number you please, say twenty or thirty, and should have a free and independent exercise of its judgment, and consequently a negative voice in the legislature.

These two bodies thus constituted, and made integral parts of the legislature, let them unite, and by joint ballot choose a governor. . . .This I know is liable to objections. . . .But as the governor is to be invested with the executive power, with consent of council, I think he ought to have a negative upon the legislative. If he is annually elective, as he ought to be, he will always have so much reverence and affection for the people, their representatives and councilors, that although you give him an independent exercise of his judgment, he will seldom use it in opposition to the two houses. . . .

The dignity and stability of government in all its branches, the morals of the people and every blessing of society, depends so much upon an upright and skillful administration of justice, that the judicial power ought to be distinct from both the legislative and executive, and independent upon both, that so it may be a check upon both, as both should be checks upon that. The judges therefore should always be men of learning and experience in the laws, of exemplary morals, great patience, calmness, coolness, and attention. Their minds should not be distracted with jarring interests; they should not be dependent upon any man or body of men. To these ends they should hold estates for life in their offices; or in other words their commissions should be during good behavior, and their salaries ascertained and established by law. For misbehavior the grand inquest of the colony, the house of representatives should impeach them before the governor and council, where . . . if convicted should be removed from their offices, and subjected to such other punishment as shall be thought proper.