No related resources

Introduction

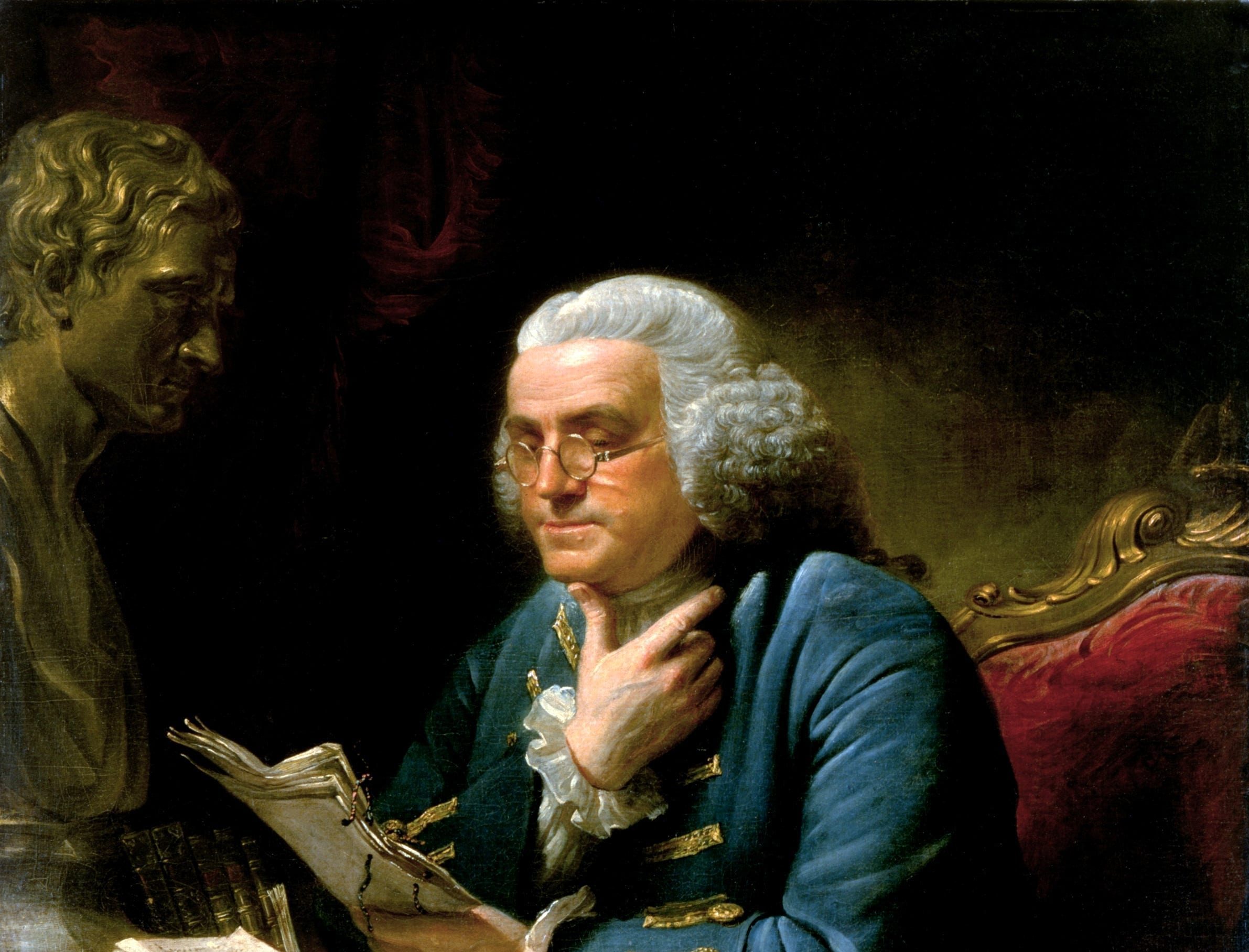

Samson Occom (1723–1792) was born in New London, Connecticut, a member of the Mohegan Nation. The Mohegan had split from the Pequot in 1631, just a few years before the Pequot War. When he was nineteen, Occom was sent to study at Moor’s Charity School for indigent young men, operated by Eleazar Wheelock, where he remained for four years. Afterward Occam became a celebrated Christian preacher and missionary to other Indian tribes.

In 1765 Occom went to London to raise funds to help Wheelock educate Indians. He stayed more than two years and raised a substantial amount. Unfortunately, upon his return he found that his teacher was largely abandoning Indian education. In 1769 Wheelock moved his school to New Hampshire and reorganized it as Dartmouth College. The money Occom had raised for Indian education became the endowment for the new college. The move and Occom’s discovery that Wheelock had lost his passion for educating Natives caused a permanent breach between teacher and pupil.

Occom’s best known written work is his 1772 “Sermon Preached at the Execution of Moses Paul, an Indian,” which was an early bestseller after its publication. Less known is the short autobiography he penned in 1768 to correct misrepresentations made about him by some white men. The document, from which this excerpt was taken, is the earliest known autobiography by an Indigenous person in North America.

Samuel Occom, Autobiography, https://collections.dartmouth.edu/occom/html/normalized/768517-normalized.html.

From the Time of Our Reformation till I Left Mr. Wheelock’s

When I was 16 years of age, we heard a strange rumor among the English that there were extraordinary ministers preaching from place to place and a strange concern among the white people. This was in the spring of the year. But we saw nothing of these things, till some time in the summer, when some ministers began to visit us and preach the Word of God; and the common people all came frequently and exhorted us to the things of God, which it please the Lord, as I humbly hope, to bless and accompany with divine influence to the conviction and saving conversion of a number of us; amongst whom I was one that was impressed with the things we had heard. These preachers did not only come to us, but we frequently went to their meetings and churches. After I was awakened and converted, I went to all the meetings, I could come at; and continued under trouble of mind about 6 months; at which time I began to learn the English letters; got me a primer,1 and used to go to my English neighbors frequently for assistance in reading, but went to no school. And when I was 17 years of age, I had, as I trust, a discovery of the way of salvation through Jesus Christ, and was enabled to put my trust in him alone for life and salvation. From this time the distress and burden of my mind was removed, and I found serenity and pleasure of soul, in serving God. By this time I just began to read in the New Testament without spelling,2 and I had a stronger desire still to learn to read the Word of God, and at the same time had an uncommon pity and compassion to my poor brethren according to the flesh.3 I used to wish I was capable of instructing my poor kindred. I used to think, if I could once learn to read I would instruct the poor children in reading, and used frequently to talk with our Indians concerning religion. This continued till I was in my 19th year: by this time I could read a little in the Bible. At this time my poor mother was going to Lebanon,4 and having had some knowledge of Mr. Wheelock and hearing he had a number of English youth under his tuition, I had a great inclination to go to him and be with him a week or a fortnight, and desired my mother to ask Mr. Wheelock whether he would take me a little while to instruct me in reading. Mother did so; and when she came back, she said Mr. Wheelock wanted to see me as soon as possible. So I went up, thinking I should be back again in a few days; when I got up there, he received me with kindness and compassion and instead of staying a fortnight or three weeks, I spent 4 years with him.

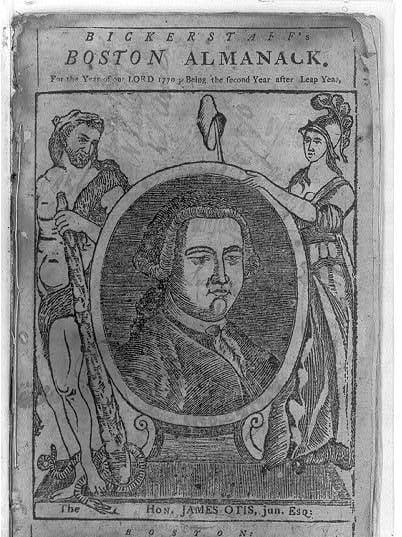

After I had been with him some time, he began to acquaint his friends of my being with him, and of his intentions of educating me, and my circumstances. And the good people began to give some assistance to Mr. Wheelock, and gave me some old and some new clothes. Then he represented the case to the honorable commissioners at Boston, who were commissioned by the honorable society in London for propagating the gospel among the Indians in New England and parts adjacent,5 and they allowed him £60 in old tender, which was about £6 sterling, and they continued it 2 or 3 years, I can’t tell exactly. While I was at Mr. Wheelock’s, I was very weakly and my health much impaired, and at the end of 4 years, I over strained my eyes to such a degree, I could not pursue my studies any longer; and out of these 4 years I lost just about one year; and was obliged to quit my studies.

From the Time I Left Mr. Wheelock till I Went to Europe

As soon as I left Mr. Wheelock, I endeavored to find some employ among the Indians; went to Nahantuck,6 thinking they may want a schoolmaster, but they had one; then went to Narraganset, and they were indifferent about a school, and went back to Mohegan, and heard a number of our Indians were going to Montauk, on Long Island, and I went with them, and the Indians there were very desirous to have me keep a school amongst them, and I consented, and went back a while to Mohegan and some time in November I went on the island, I think it is 17 years ago last November. I agreed to keep school with them half a year, and left it with them to give me what they pleased; and they took turns to provide food for me. I had near 30 scholars this winter; I had an evening school too for those that could not attend the day school—and began to carry on their meetings, they had a minister, one Mr. Horton, the Scotch society’s missionary; but he spent, I think two-thirds of his time at Shenecock, 30 miles from Montauk. We met together 3 times for divine worship every sabbath and once on every Wednesday evening. I (used) to read the Scriptures to them and used to expound upon some particular passages in my own tongue.7 Visited the sick and attended their burials.

When the half year expired, they desired me to continue with them, which I complied with, for another half year, when I had fulfilled that, they were urgent to have me stay longer. So I continued amongst them till I was married, which was about 2 years after I went there. And continued to instruct them in the same manner as I did before. After I was married awhile, I found there was need of a support more than I needed while I was single, and made my case known to Mr. Buell and to Mr. Wheelock, and also the needy circumstances and the desires of these Indians of my continuing amongst them, and the commissioners were so good as to grant £15 a year sterling.

And I kept on in my service as usual, yea, I had additional service; I kept school as I did before and carried on the religious meetings as often as ever, and attended sick and their funerals, and did what writings they wanted, and often sat as a judge to reconcile and decide their matters between them, and had visitors of Indians from all quarters; and, as our custom is, we freely entertain all visitors. And was fetched often from my tribe and from others to see into their affairs both religious, and temporal, besides my domestic concerns. And it pleased the Lord to increase my family fast—and soon after I was married, Mr. Horton left these Indians and the Shenecock and after this I was (alone) and then I had the whole care of these Indians at Montauk, and visited the Shenecock Indians often. Used to set out Saturdays toward night and come back again Mondays. I have been obliged to set out from home after sunset, and ride 30 miles in the night, to preach to these Indians. And some Indians at Shenecock sent their children to my school at Montauk, I kept one of them some time, and had a young man a half year from Mohegan, a lad from Nahantuck, who was with me almost a year; and had little or nothing for keeping them.

My method in the school was, as soon as the children got together and took their proper seats, I prayed with them, then began to hear them. I generally began (after some of them could spell and read) with those that were yet in their alphabets, so around, as they were properly seated till I got through and I obliged them to study their books, and to help one another. When they could not make out a hard word they brought it to me—and I usually heard them, in the summer season 8 times a day 4 in the morning, and in the afternoon. In the winter season 6 times a day, as soon as they could spell, they were obliged to spell whenever they wanted to go out. I concluded with prayer; I generally heard my evening scholars 3 times round, and as they go out the school, every one that can spell is obliged to spell a word, and to go out leisurely one after another. I catechized 3 or 4 times a week according to the assembly’s shout or catechism, and many times proposed questions of my own, and in my own tongue. I found difficulty with some children, who were somewhat dull, most of these can soon learn to say over their letters, they distinguish the sounds by the ear, but their eyes can’t distinguish the letters, and the way I took to cure them was by making an alphabet on small bits of paper, and glued them on small chips of cedar after this manner A B & C. I put these on letters in order on a bench then point to one letter and bid a child to take notice of it, and then I order the child to fetch me the letter from the bench; if he brings the letter, it is well, if not he must go again and again till he brings the right letter. When they can bring any letters this way, then I just jumble them together, and bid them to set them in alphabetical order, and it is a pleasure to them; and they soon learn their letters this way.

I frequently discussed or exhorted my scholars, in religious matters. My method in our religious meetings was this; sabbath morning we assemble together about 10 o’clock and begin with singing; we generally sung Dr. Watt’s Psalms or Hymns.8 I distinctly read the Psalm or hymn first, and then gave the meaning of it to them, after that sing, then pray, and sing again after prayer. Then proceed to read from suitable portion of Scripture, and so just give the plain sense of it in familiar discourse and apply it to them. So continued with prayer and singing. In the afternoon and evening we proceed in the same manner, and so in Wednesday evening. Sometime after Mr. Horton left these Indians, there was a remarkable revival of religion among these Indians and many were hopefully converted to the saving knowledge of God in Jesus. It is to be observed before Mr. Horton left these Indians they had some prejudices infused in their minds, by some enthusiastical exhorters from New England, against Mr. Horton, and many of them had left him; by this means he was discouraged, and was disposed from these Indians. And being acquainted with the enthusiasts in New England and the make and the disposition of the Indians I took a mild way to reclaim them. I opposed them not openly but let them go on in their way, and whenever I had an opportunity, I would read such pages of the Scriptures [as] I thought would confound their notions, and I would come to them with all authority, saying “these saith the Lord”; and by this means, the Lord was pleased to bless my poor endeavors, and they were reclaimed, and brought to hear almost any of the ministers.

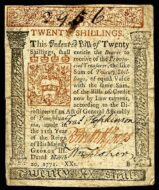

I am now to give an account of my circumstances and manner of living. I dwelt in a wigwam, a small hut with small poles and covered with mats made of flags, and I was obliged to remove twice a year, about 2 miles distance, by reason of the scarcity of wood, for in one neck of land they planted their corn, and in another, they had their wood, and I was obliged to have my corn carted and my hay also, and I got my ground plowed every year, which cost me about 12 shillings an acre; and I kept a cow and a horse, for which I paid 21 shillings every year York currency,9 and went 18 miles to mill for every dust of meal we used in my family. I hired or joined with my neighbors to go to mill, with a horse or ox cart, or on horseback, and some time went myself. My family increasing fast, and my visitors also. I was obliged to contrive every way to support my family; I took all opportunities to get something to feed my family daily. I planted my own corn, potatoes, and beans; I used to be out hoeing my corn sometimes before sunrise and after my school is dismissed, and by this means I was able to raise my own pork, for I was allowed to keep 5 swine. Some mornings and evenings I would be out with my hook and line to catch fish and in the fall of year and in the spring, I used my gun, and fed my family with fowls. I could more than pay for my powder and shot with feathers. At other times I bound old books for Easthampton people, made wooden spoons and ladles, stocked guns, and worked on cedar to make pails, (piggins),10 and churns, etc. Besides all these difficulties I met with adverse providence, I bought a mare, had it but a little while, and she fell into the quicksand and died. After awhile bought another, I kept her about half year, and she was gone, and I never have heard of nor seen her from that day to this; it was supposed some rogue stole her. I got another and [it] died with a distemper, and last of all I bought a young mare and kept her till she had one colt, and she broke her leg and died, and presently after the colt died also. In the whole I lost 5 horse kind; all these losses helped to pull me down; and by this time I got greatly in debt and acquainted my circumstances to some of my friends, and they represented my case to the commissioners of Boston, and interceded with them for me, and they were pleased to vote £15 for my help, and soon after sent a letter to my good friend at New London, acquainting him that they had superseded their vote; and my friends were so good as to represent my needy circumstances still to them, and they were so good at last, as to vote £15 and sent it, for which I am very thankful; and the Reverend Mr. Buell was so kind as to write in my behalf to the gentlemen of Boston; and he told me they were much displeased with him, and heard also once again that they blamed me for being extravagant; I can’t conceive how these gentlemen would have me live. I am ready to (forgive) their ignorance, and I would wish they had changed circumstances with me but one month, that they may know, by experience what my case really was; but I am now fully convinced that it was not ignorance, for I believe it can be proved to the world that these same gentlemen gave a young missionary, a single man, 100 pounds for one year, and £50 for an interpreter, and £30 for an introducer; so it cost them £180 in one single year, and they sent too where there was no need of a missionary.

Now you see what difference they made between me and other missionaries; they gave me £180 for 12 years’ service, which they gave for one year’s services in another mission. In my service (I speak like a fool, but I am constrained) I was my own interpreter. I was both a schoolmaster and minister to the Indians, yea, I was their ear, eye, and hand, as well as mouth. I leave it with the world, as wicked as it is, to judge whether I ought not to have had half as much, they gave a young man just mentioned which would have been but £50 a year; and if they ought to have given me that, I am not under obligations to them, I owe them nothing at all; what can be the reason that they used me after this manner? I can’t think of anything, but this as a poor Indian boy said, who was bound out to an English family,11 and he used to drive plow for a young man, and he whipt and beat him almost every day, and the young man found fault with him, and complained of him to his master and the poor boy was called to answer for himself before his master, and he was asked, what it was he did, that he was so complained of and beat almost every day. He said, he did not know, but he supposed it was because he could not drive any better; but says he, I drive as well as I know how; and at other times he beats me, because he is of a mind to beat me; but says he believes he beats me for the most of the time “because I am an Indian.”

So I am ready to say, they have used me thus, because I can’t influence the Indians so well as other missionaries; but I can assure them I have endeavored to teach them as well as I know how; but I must say, “I believe it is because I am a poor Indian.” I can’t help that God has made me so; I did not make myself so.

- 1. A book used to teach reading.

- 2. That is, without ceasing.

- 3. “Brethern according to the flesh” referred to his fellow Indians, whom he distinguished from his spiritual brothers; i.e., fellow Christians.

- 4. Lebanon, Connecticut. The town was in traditional Mohegan territory and was first settled by them. They called the area Poquechaneed and used it primarily for hunting.

- 5. The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, a Church of England missionary organization chartered by the king in 1701.

- 6. Nahantuck is near present-day New London, CT, as is Narraganset, next mentioned. Shenecock and Montauk are on the eastern end of Long Island, New York. These place-names are also the names of the Indian tribes that lived there.

- 7. In his native language.

- 8. Isaac Watts (1674–1748) was an English Congregational minister and hymn writer.

- 9. Money issued by the colony and state of New York.

- 10. Small wooden pails.

- 11. "Bound out” means to work for someone as a servant in return for food and lodging.

The Resolves of Parliament

February 09, 1769

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.