Introduction

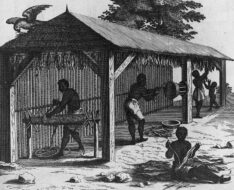

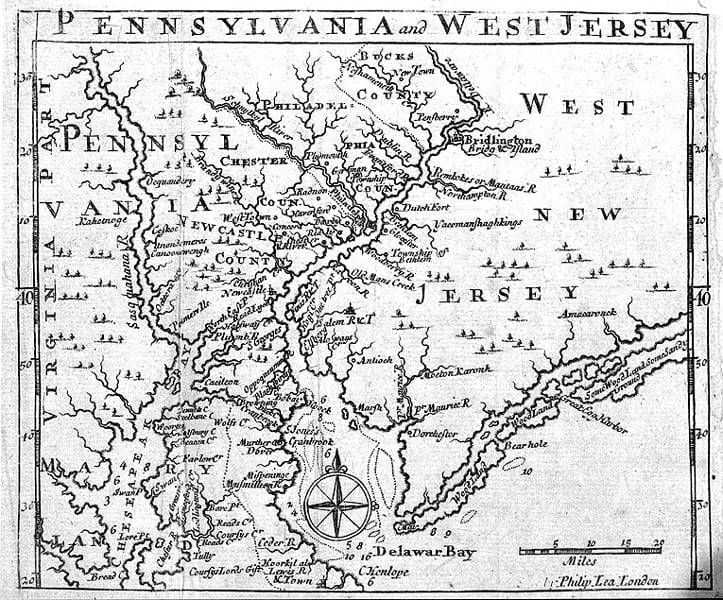

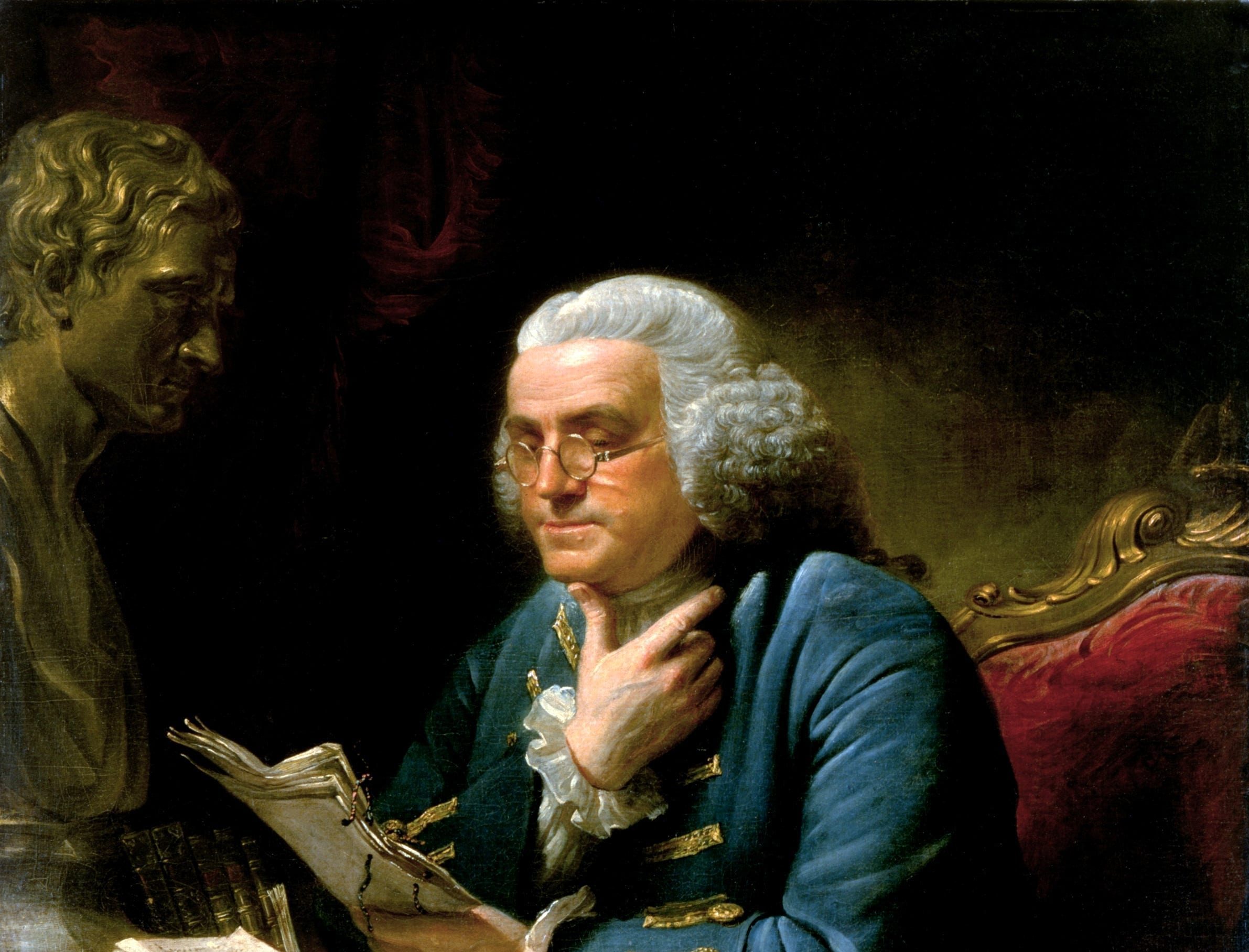

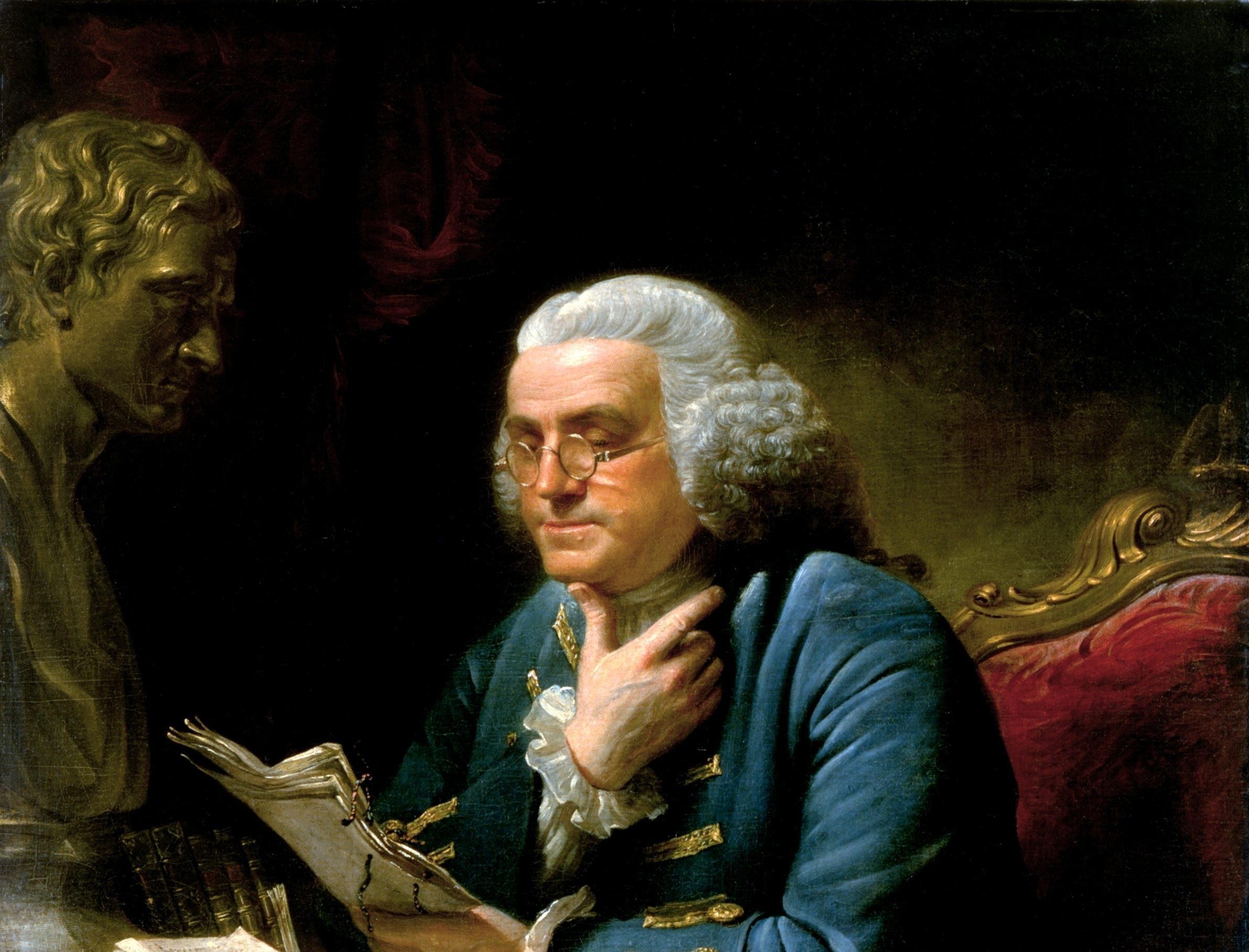

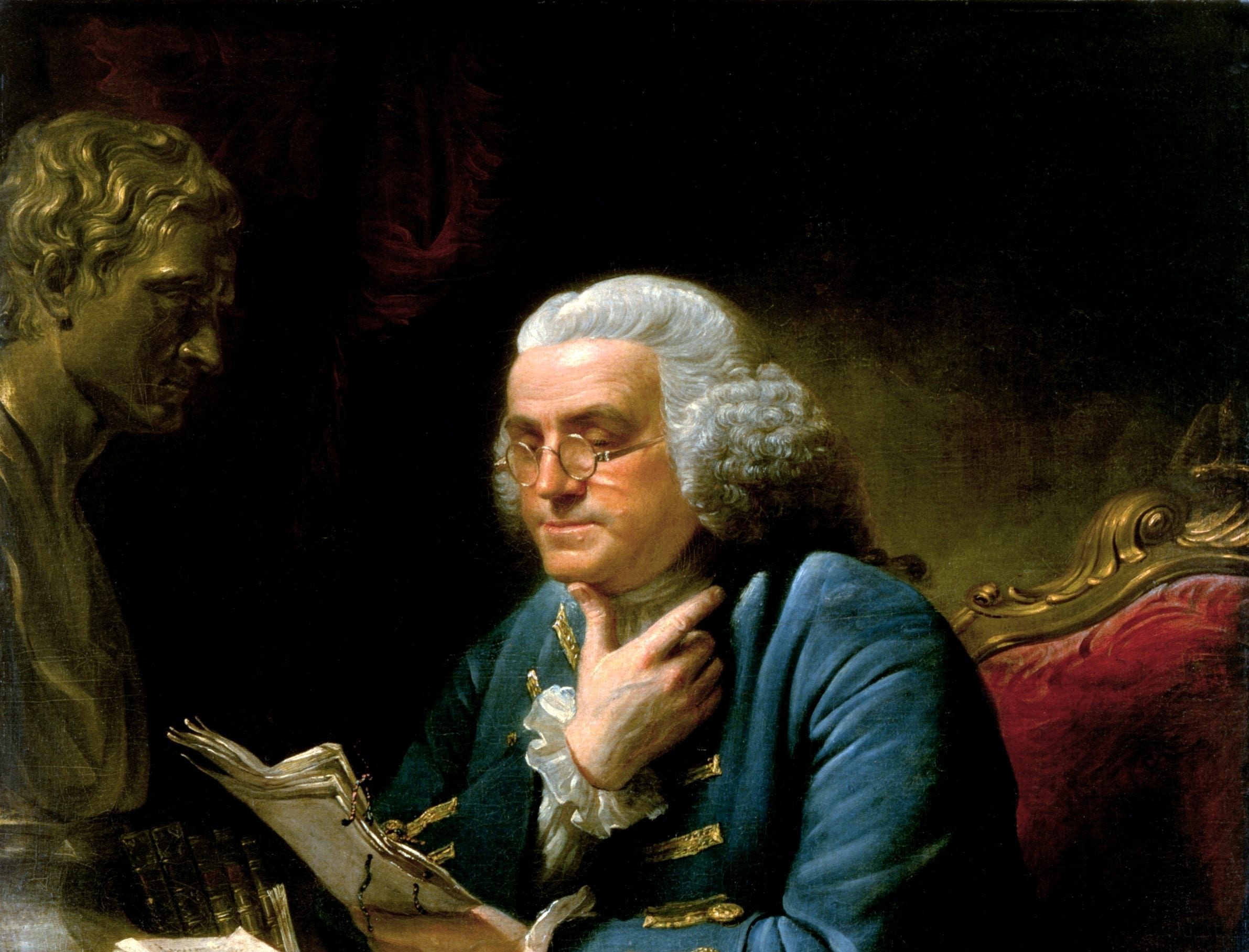

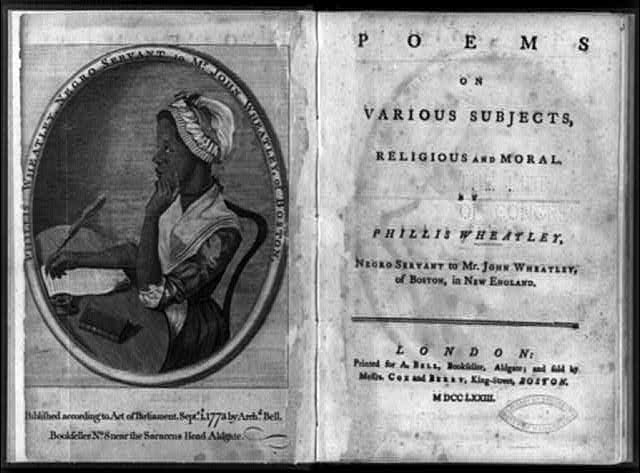

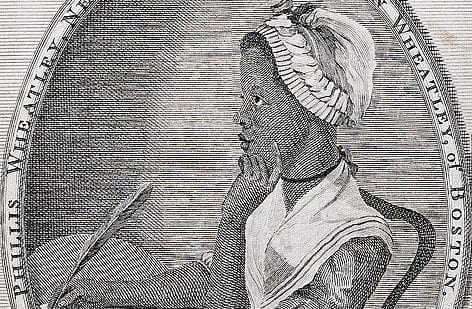

Phillis Wheatley (1753–1784) was captured in Africa as a young child, and brought to Boston, Massachusetts. There, she was sold as a slave to John Wheatley who was immediately impressed by her intellect and encouraged Phyllis to learn to read English, so that she might study the Bible. “As to her WRITING, her own curiosity led her to it,” he later recalled. After Wheatley published a book of her poems in 1773, with the help of Wheatley and his family, Wheatley emancipated her. She later married and had a child. She and her husband did not prosper, and Wheatley died at 31.

In the first of the poems reprinted here, Wheatley reflected on her captivity and conversion to Christianity. In the second, she used her experience of servitude to explain the significance of the liberty much on the minds of many in the colonies.

—David Tucker

On being brought from Africa to America

’TWAS mercy brought me from my pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there’s a God, that there’s a Savior too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

“Their color is a diabolic die.”

Remember, Christians, Negroes, black as Cain,

May be refined, and join the angelic train.

To the Right Honorable William, Earl of Dartmouth

Hail, happy day, when, smiling like the morn,

Fair Freedom rose New-England to adorn:

The northern clime beneath her genial ray,

Dartmouth, congratulates thy blissful sway:

Elate with hope her race no longer mourns,

Each soul expands, each grateful bosom burns,

While in thine hand with pleasure we behold

The silken reins, and Freedom’s charms unfold.

Long lost to realms beneath the northern skies

She shines supreme, while hated faction dies:

Soon as appear’d the Goddess long desir’d,

Sick at the view, she languish’d and expir’d;

Thus from the splendors of the morning light

The owl in sadness seeks the caves of night.

No more, America, in mournful strain

Of wrongs, and grievance unredress’d complain,

No longer shalt thou dread the iron chain,

Which wanton Tyranny with lawless hand

Had made, and with it meant t’ enslave the land.

Should you, my lord, while you peruse my song,

Wonder from whence my love of Freedom sprung,

Whence flow these wishes for the common good,

By feeling hearts alone best understood,

I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate

Was snatch’d from Afric’s fancy’d happy seat:

What pangs excruciating must molest,

What sorrows labour in my parent’s breast?

Steel’d was that soul and by no misery mov’d

That from a father seiz’d his babe belov’d:

Such, such my case. And can I then but pray

Others may never feel tyrannic sway?

For favours past, great Sir, our thanks are due,

And thee we ask thy favours to renew,

Since in thy pow’r, as in thy will before,

To sooth the griefs, which thou did’st once deplore.

May heav’nly grace the sacred sanction give

To all thy works, and thou for ever live

Not only on the wings of fleeting Fame,

Though praise immortal crowns the patriot’s name,

But to conduct to heav’ns refulgent fane,[3]

May fiery coursers sweep th’ ethereal plain,

And bear thee upwards to that blest abode,

Where, like the prophet, thou shalt find thy God.