1774: The Year Between Resistance and Rebellion

Today we continue our exploration of Teaching American History’s two-volume document collection, Documents and Debates in American History and Government.

In July of 1774, as colonial resistance to British rule consumed the American colonies, the Virginia House of Burgesses asked thirty-one-year old Thomas Jefferson to draft instructions for the colony’s delegates to the First Continental Congress. Jefferson’s draft argued that Parliament had “no right to exercise authority” over the colonies and hinted that King George might be blamed for the turmoil if Parliament did not back down. The Virginia House set aside Jefferson’s draft and adopted a more conciliatory approach toward the crown. Jefferson quickly arranged to have his work published as A Summary View of the Rights of British America. Jefferson’s pamphlet was widely read in America and London, and he became known as a talented wordsmith and radical proponent of the colonial cause.

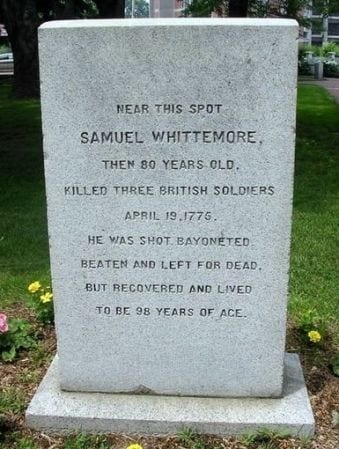

Meanwhile, in Massachusetts, seventy-eight-year-old Samuel Whittemore served as a civic spokesman for his colony’s resistance. Like Jefferson, he helped draft instructions for various Massachusetts delegations, joining strong stands against the Stamp Act in 1766 and the Tea Act in 1773.

Jefferson’s career was getting started, while Whittemore’s life seemed to be drawing to a close, when armed conflict erupted in 1775. Jefferson’s weapon of choice in the war remained his eloquent and forceful pen, but aged Samuel Whittemore chose more conventional weapons. On April 19, 1775, as British regulars retreated to Boston following their skirmishes with American militia in Lexington and Concord, Whittemore shot and killed at least two British soldiers, wounding another before being surrounded. He was stabbed, shot in the face, and left for dead. Yet, he lived until February of 1793, long enough to see George Washington become President under the United States’ new Constitution.

What inspired these two men, from two different colonies, separated in age by over 45 years and in geography by nearly six hundred miles, to abandon their allegiance to the British empire, risk their lives, and join the revolutionary cause? Is it true, as John Adams argued in a letter he wrote Jefferson in 1815, that the revolution occurred first in “the minds of the people”? If so, what led Americans to begin considering themselves no longer British subjects, bu rather American patriots?

Teachers often use questions like these to guide the teaching of American history in their classrooms. One of my favorite undergraduate professors used to say, “it is more important to ask the right questions than to have answers.” We embrace that philosophy at Teaching American History. We believe the best way to learn and teach American history and government is to ask thoughtful questions of the authors of original documents. In Chapter 5, Between Resistance and Rebellion from our Documents and Debates two-volume collection, we ask what was in the American people’s minds in the critical year before the American Revolutionary War began. We encourage you to explore this chapter with your students and challenge them to find their own answers.

Documents in this chapter include:

A. New Yorkers Celebrate “Loyalty” and the Anniversary of the Repeal of the Stamp Act, March 18, 1774

B. Gouverneur Morris, “We Shall be Under the Domination of a Riotous Mob,” May 20, 1774

C. Thomas Jefferson, A Summary View of the Rights of British America, August 177

D. Philadelphia Welcomes the First Continental Congress, September 9, 1774

E. Joseph Galloway, Plan of Union, September 28, 1774

F. General Thomas Gage, “I am to Do My Duty,” October 20, 1777

We have also provided audio recordings of the chapter’s Introduction, Documents, and Study Questions. These recordings support literacy development for struggling readers and the comprehension of challenging text for all students.

Teaching American History’s We the Teachers blog will feature Documents and Debates with their accompanying audio recordings each month until recordings of all 29 chapters are complete. In today’s post, we feature Volume I, Chapter 5: Between Resistance and Rebellion. On October 20, we will highlight Chapter 20: Progressive Foreign Policy; The Philippines from Volume II of Documents and Debates in American History.