No study questions

No related resources

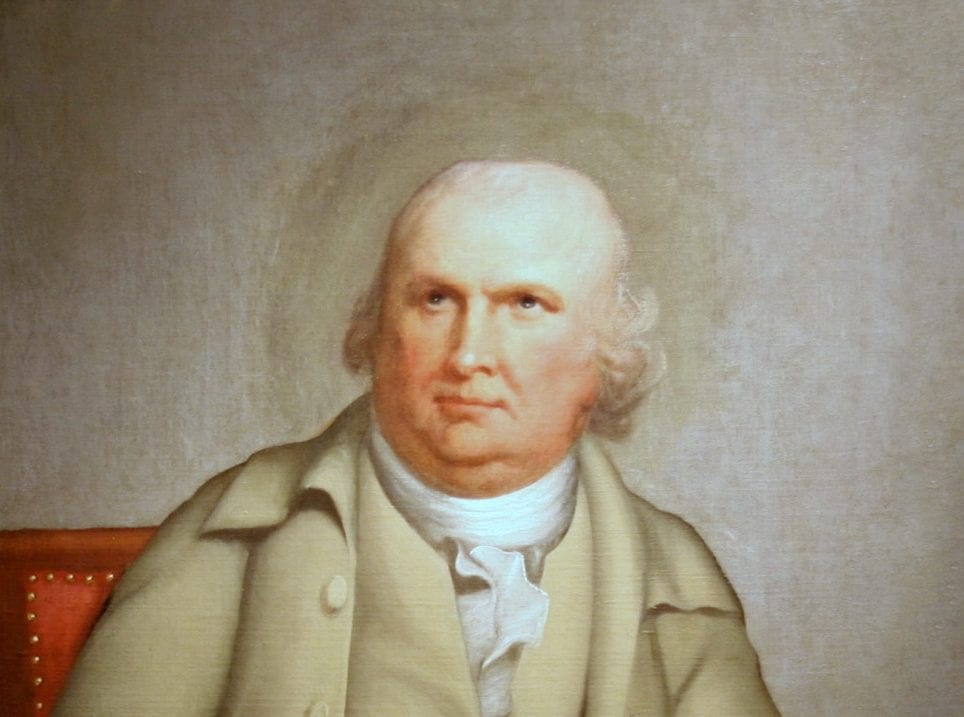

During the whole month of November, the concurring accounts which were transmitted to Government, enumerating Lord Cornwallis’s embarrassments and the positions taken by the enemy, augmented the anxiety of the Cabinet. Lord George Germain in particular, conscious that on the prosperous or adverse termination of that expedition must depend the fate of the American contest, his own stay in office, as well as probably the duration of the Ministry, felt, and even expressed to his friends, the strongest uneasiness on the subject. The meeting of Parliament meanwhile stood fixed for the 27th of November.

On Sunday the 25th about noon, official intelligence of the surrender of the British forces at Yorktown arrived from Falmouth at Lord George Germain’s house in Pall-Mall. Lord Walsingham, who, previous to his father Sir William de Grey’s elevation to the peerage, had been Under-Secretary of State in that department, and who was selected to second the address in the House of Peers on the subsequent Tuesday, happened to be there when the messenger brought the news. Without communicating it to any other person, Lord George, for the purpose of dispatch, immediately got with him into a hackney-coach and drove to Lord Stormont’s residence in Portland Place. Having imparted to him the disastrous information and taken him into the carriage, they instantly proceeded to the Chancellor’s house in Great Russell Street, Bloomsbury, whom they found at home, when after a short consultation, they determined to lay it themselves in person before Lord North.

He had not received any intimation of the event when they arrived at his door in Downing Street between one and two o’clock. The First Minister’s firmness, and even his presence of mind, which had withstood the [Gordon] riots of 1780, gave way for a short time under this awful disaster. I asked Lord George afterwards how he took the communication when made to him. “As he would have taken a ball in his breast,” replied Lord George. For he opened his arms, exclaiming wildly, as he paced up and down the apartment during a few minutes, “O God! it is all over! “words which he repeated many times under emotions of the deepest consternation and distress.

When the first agitation of their minds had subsided, the four Ministers discussed the question whether or not it might be expedient to prorogue Parliament for a few days; but as scarcely an interval of forty-eight hours remained before the appointed time of assembling, and as many members of both Houses were already either arrived in London or on the road, that proposition was abandoned. It became, however, indispensable to alter and almost to model anew the King’s speech, which had been already drawn up and completely prepared for delivery from the throne. This alteration was therefore made without delay, and at the same time Lord George Germain, as Secretary for the American Department, sent off a dispatch to his Majesty, who was then at Kew, acquainting him with the melancholy termination of Lord Cornwallis’s expedition. Some hours having elapsed before these different but necessary acts of business could take place, the Ministers separated, and Lord George Germain repaired to his office in Whitehall. There he found a confirmation of the intelligence, which arrived about two hours after the first communication, having been transmitted from Dover, to which place it was forwarded from Calais with the French account of the same event.

I dined on that day at Lord George’s, and though the information which had reached London in the course of the morning from two different quarters was of a nature not to admit of long concealment, yet it had not been communicated either to me or to any individual of the company (as it might have been through the channel of common report), when I got to Pall-Mall between five and six o’clock. Lord Walsingham, who likewise dined there, was the only guest that had become acquainted with the fact. The party, nine in number, sat down to table. Lord George appeared serious, though he manifested no discomposure. Before the dinner was finished, one of his servants delivered him a letter, brought back by the messenger who had been dispatched to the King.

Lord George opened and perused it, then looking at Lord Walsingham, to whom he exclusively directed his observation, “The King writes,” said he, “just as he always does, except that I observe he has omitted to mark the hour and the minute of his writing with his usual precision.” This remark, though calculated to awaken some interest, excited no comment; and while the ladies, Lord George’s three daughters, remained in the room we repressed our curiosity. But they had no sooner withdrawn than, Lord George having acquainted us that from Paris information had just arrived of the old Count de Maurepas, First Minister, lying at the point of death, “It would grieve me,” said I, “to finish my career, however far advanced in years, were I First Minister of France, before I had witnessed the termination of this great contest between England and America.”

“He has survived to witness that event,” replied Lord George with some agitation. Utterly unsuspicious as I was of the fact which had happened beyond the Atlantic, I conceived him to allude to the indecisive naval action fought at the mouth of the Chesapeake early in the preceding month of September between Admiral Graves and Count de Grasse: an engagement which in its results might prove most injurious to Lord Cornwallis.

Under this impression, “My meaning,” said I, “is that if I were the Count de Maurepas, I should wish to live long enough to behold the final issue of the war in Virginia.”

“He has survived to witness it completely,” answered Lord George. “The army has surrendered, and you may peruse the particulars of the capitulation in that paper,” taking at the same time one from his pocket, which he delivered into my hand not without visible emotion. By his permission I read it aloud, while the company listened in profound silence. We then discussed its contents as affecting the Ministry, the country and the war. It must be confessed that they were calculated to diffuse a gloom over the most convivial society, and that they opened a wide field for political speculation.

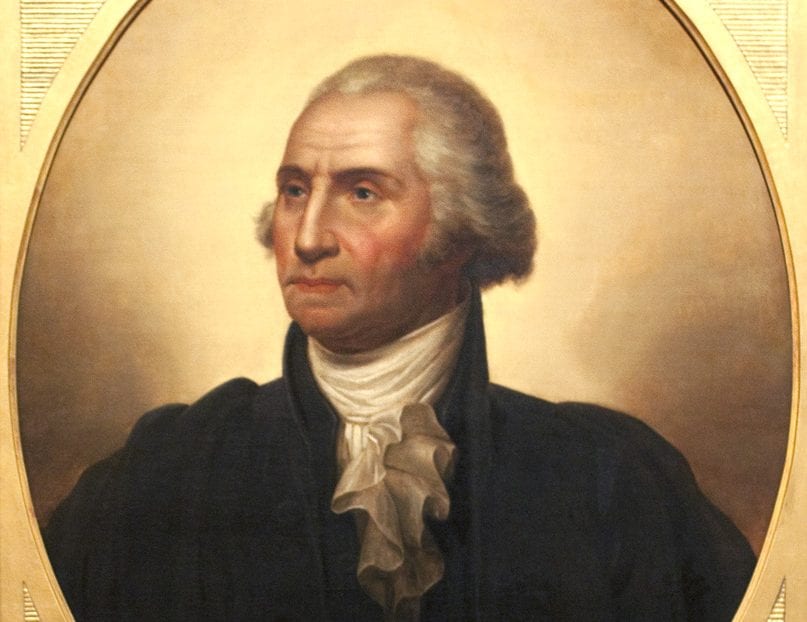

After perusing the account of Lord Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown, it was impossible not to feel a lively curiosity to know how the King had received the intelligence, as well as how he had expressed himself in his note to Lord George Germain on the first communication of so painful an event. He gratified our wish by reading it to us, observing, at the same time, that it did the highest honour to his Majesty’s fortitude, firmness and consistency of character. The words made an impression on my memory which the lapse of more than thirty years has not erased, and I shall here commemorate its tenor as serving to show how that prince felt and wrote under one of the most afflicting as well as humiliating occurrences of his reign. The billet ran nearly to this effect: “I have received with sentiments of the deepest concern the communication which Lord George Germain has made me of the unfortunate result of the operations in Virginia. I particularly lament it on account of the consequences connected with it and the difficulties which it may produce in carrying on the public business or in repairing such a misfortune. But I trust that neither Lord George Germain nor any member of the Cabinet will suppose that it makes the smallest alteration in those principles of my conduct which have directed me in past time and which will always continue to animate me under every event in the prosecution of the present contest.”

Not a sentiment of despondency or of despair was to be found in the letter, the very handwriting of which indicated composure of mind. What-ever opinion we may entertain relative to the practicability of reducing America to obedience by force of arms at the end of 1781, we must admit that no sovereign could manifest more calmness, dignity or self-command than George III displayed in this reply.

Notes on the State of Virginia: Queries 18 and 19

December 30, 1784

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.