No related resources

Introduction

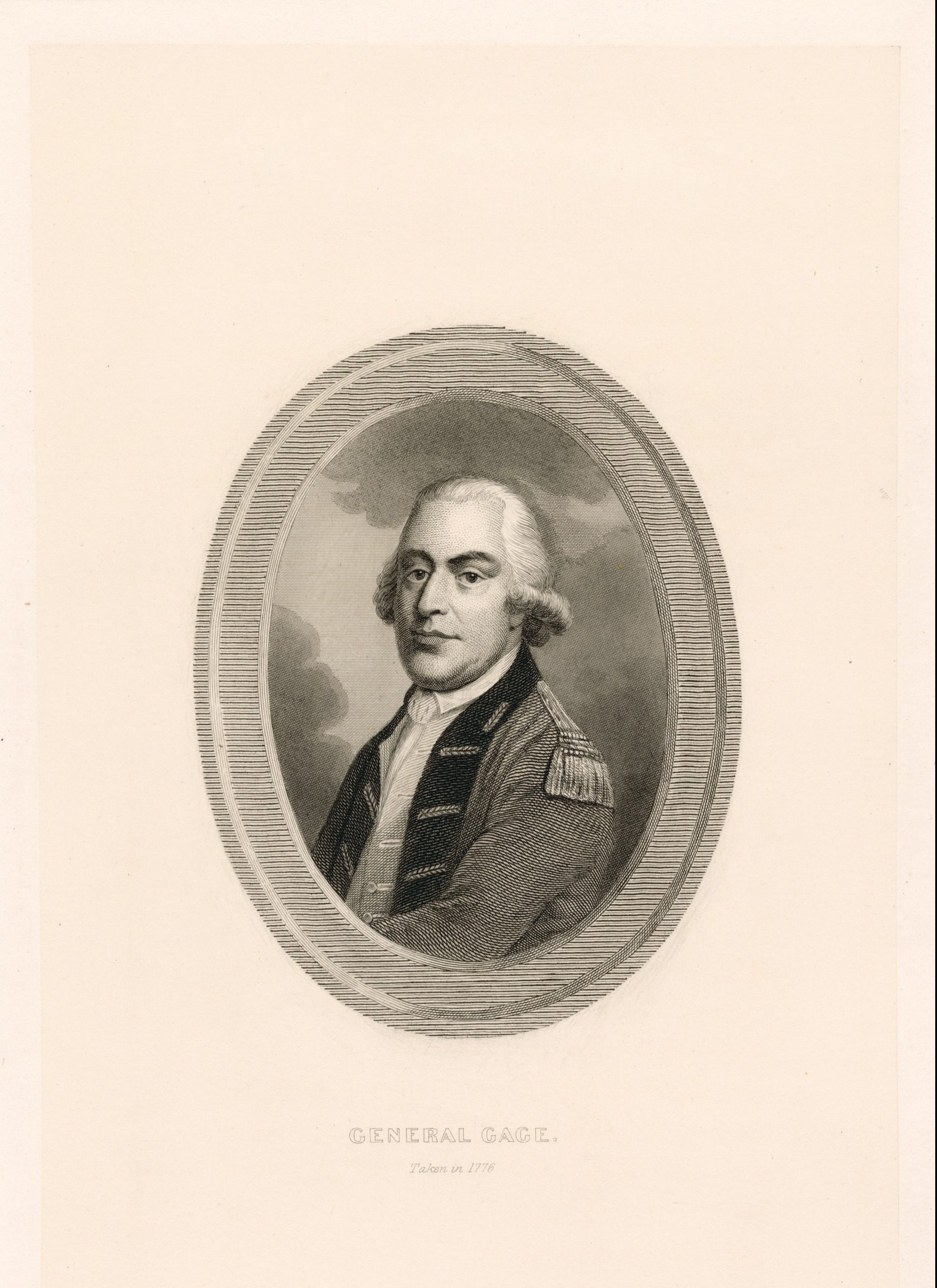

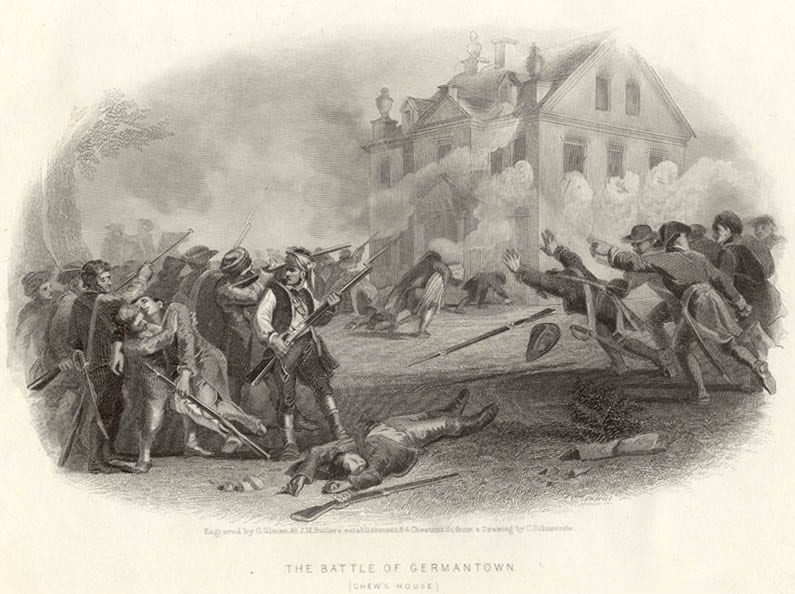

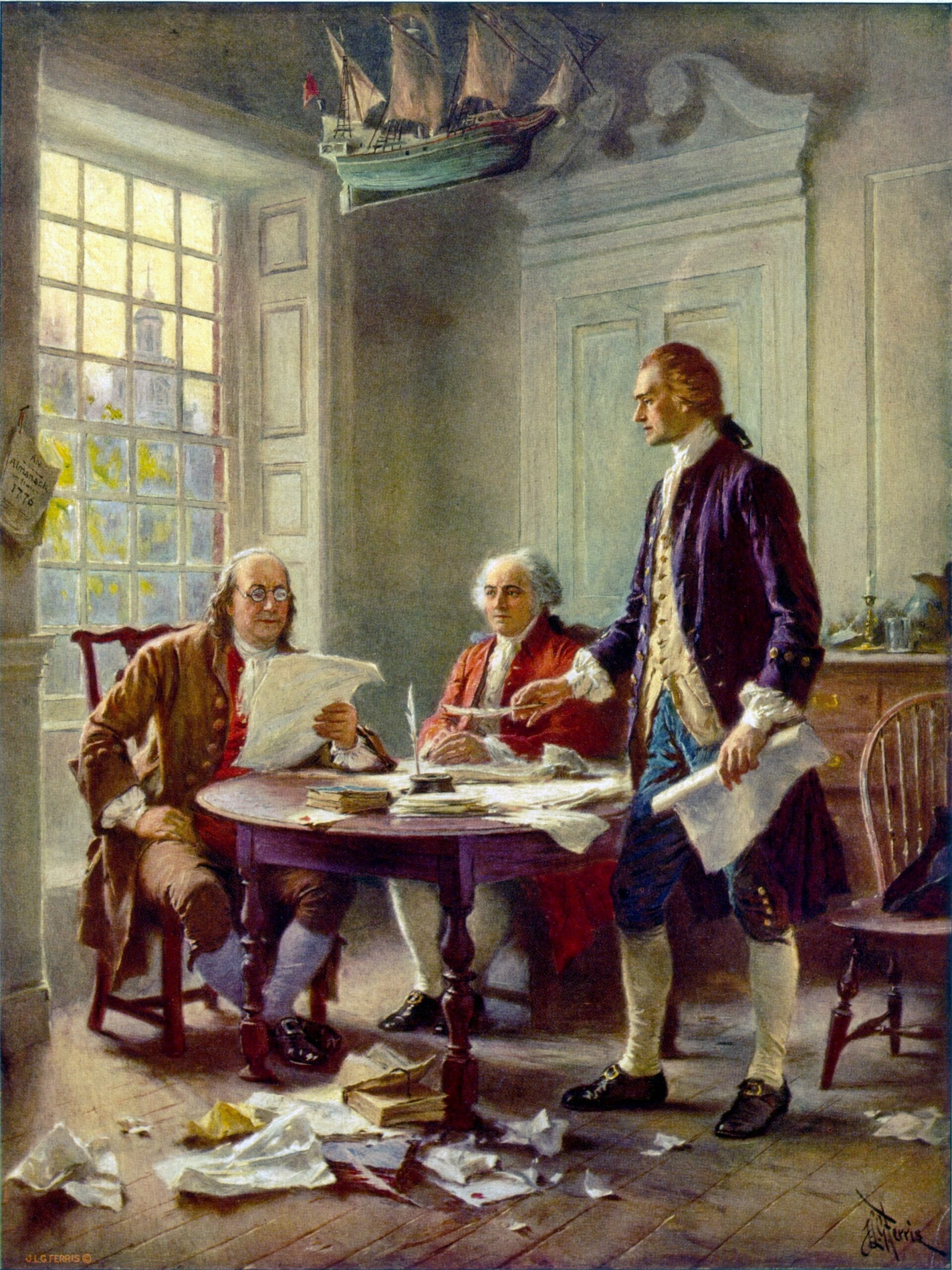

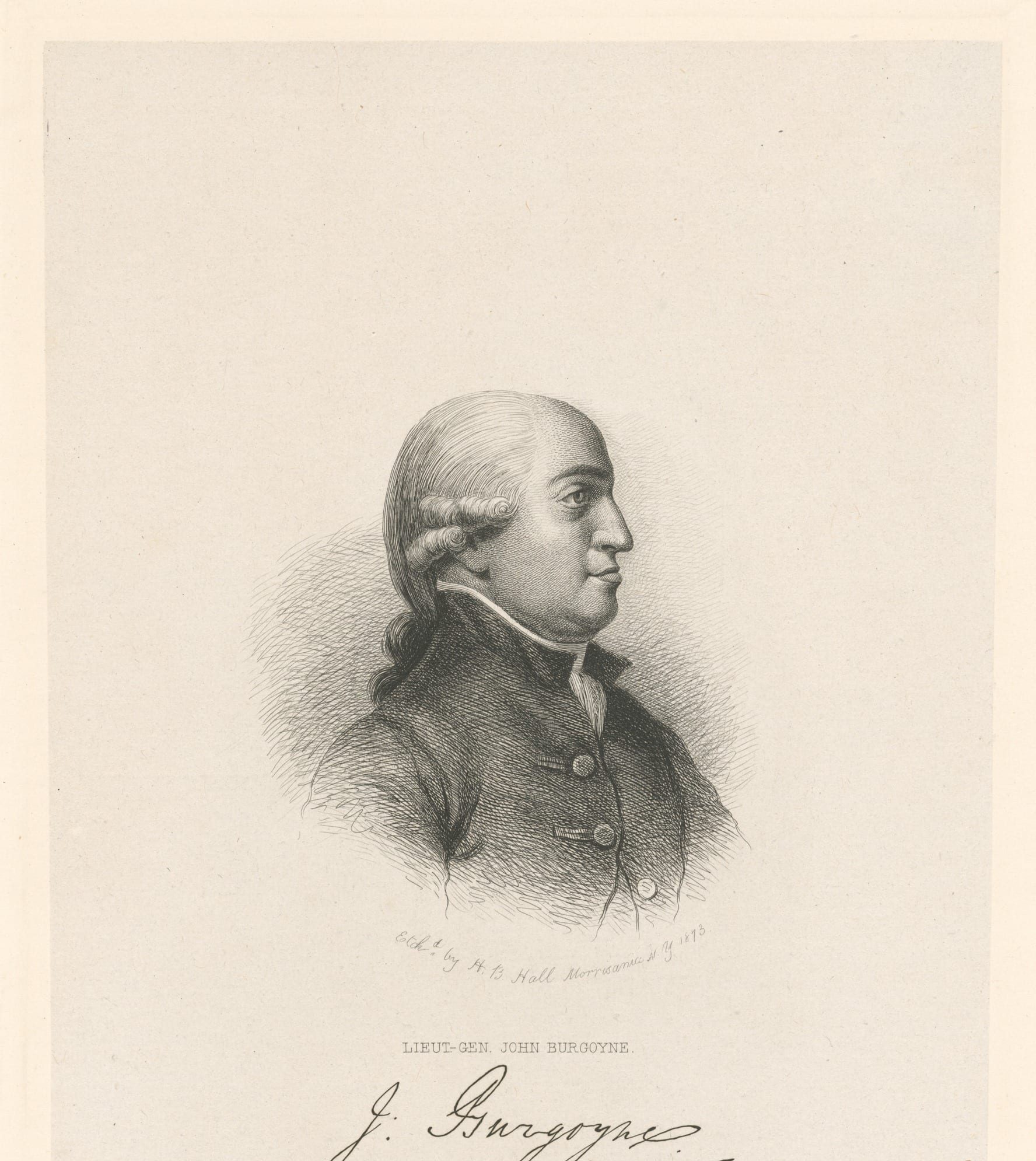

The October 1777 surrender of General John Burgoyne (1722-1792) at Saratoga shattered Britain’s northern strategy, which had aimed to isolate New England. It also emboldened the French, who in 1778 joined the war as America’s ally. This prompted General Henry Clinton (1730-1795), who after the resignation of William Howe (1729-1814) in 1777 had become the British commander-in-chief, to withdraw from Philadelphia and consolidate his forces in New York and the Caribbean. Beginning in December 1778, when Redcoats captured Savannah, a war that had started in the North and spread to the middle states shifted to the South. The belief that Loyalism remained strong in Georgia and the Carolinas constituted a central premise of the British southern strategy. In addition, Britain hoped, the prevalence of slavery in the region would cause southerners to think twice before inviting instability by taking up arms.

The account of Eliza Yonge Wilkinson (1757-1818), a 22-year-old widow who fled inland to her sister’s plantation after Redcoats attacked Beaufort in 1779, underscores the limits of these presumptions—especially when the behavior of British troops made enemies and not friends. Already highly hostile to Great Britain, Wilkinson grew increasingly bitter in the months that followed her June 1779 encounter with British forces. In addition to their 1780 capture of Charleston, Redcoats would burn her parents’ house and kill several of their slaves. Meanwhile, one of her brothers lost his life fighting for independence. After the war, Wilkinson remarried and had four children. A granddaughter, Caroline Gilman, published her letters.

Source: Caroline Gilman, ed., Letters of Eliza Wilkinson (New York, 1839), 24, 27-31. https://archive.org/details/lettersofelizawi00wilk/page/24

All this time we had not seen the face of an enemy, not an open one—for I believe private ones were daily about. One night, however, upwards of sixty dreaded Redcoats, commanded by Major Graham,[1] passed our gate, in order to surprise Lieutenant Morton Wilkinson[2] at his own house, where they understood he had a party of men. A negro wench was their informer, and also their conductor; but (thank heaven) somehow or other they failed in their attempt, and repassed our avenue early in the morning, but made a halt at the head of it, and wanted to come up; but a negro fellow, whom they had got at a neighbor’s not far from us to go as far as the ferry with them, dissuaded them from it, by saying it was not worth while, for it was only a plantation belonging to an old decrepit gentleman, who did not live there; so they took his word for it, and proceeded on. You may think how much we were alarmed when we heard this, which we did the next morning; and how many blessings the negro had from us for his consideration and pity….

Well, now comes the day of terror—the 3d of June. (I shall never love the anniversary of that day.) In the morning, fifteen or sixteen horsemen rode up to the house; we were greatly terrified, thinking them the enemy, but from their behavior, were agreeably deceived, and found them friends. They sat a while on their horses, talking to us; and then rode off, except two, who tarried a minute or two longer, and then followed the rest, who had nearly reached the gate. One of the said two [fell from his horse]…. We saw him, and sent a boy to tell him, if he was hurt, to come up to the house, and we could endeavor to do something for him. He and his companion accordingly came up; he looked very pale, and bled much; his gun, somehow in the fall, had given him a bad wound behind the ear, from whence the blood flowed down his neck and bosom plentifully. We were greatly alarmed on seeing him in this situation, and had gathered around him, some with one thing, some with another, in order to give him assistance. We were very busy examining the wound, when a negro girl ran in, exclaiming, “Oh! The king’s people are coming; it must be them, for they are all in red.” Upon this cry, the two men that were with us snatched up their guns, mounted their horses, and made off; but had not got many yards from the house, before the enemy discharged a pistol at them. Terrified almost to death as I was, I was still anxious for my friends’ safety; I tremblingly flew to the window, to see if the shot had proved fatal. When, seeing them both safe, “Thank heaven,” said I, “they’ve got off without hurt!” I’d hardly uttered this, when I heard the horses of the inhuman Britons coming in such a furious manner, that they seemed to tear up the earth, and the riders at the same time bellowing out the most horrid curses imaginable; oaths and imprecations which chilled my whole frame. Surely, thought I, such horrid language denotes nothing less than death; but I’d no time for thought—they were up to the house—entered with drawn swords and pistols in their hands; indeed, they rushed in, in the most furious manner, crying out, “Where’s these rebel bastards?” (Pretty language to ladies from the once famed Britons!) That was the first salutation! The moment they espied us, off went our caps. (I always heard say none but women pulled caps!)[3] And for what, think you? Why, only to get a paltry stone-and-wax pin, which kept them on our heads; at the same time uttering the most abusive language imaginable, and making as if they’d hew us to pieces with their swords. But it’s not in my power to describe the scene: it was terrible to the last degree; and, what augmented it, they had several armed negroes with them, who threatened and abused us greatly. They then began to plunder the house of everything they thought valuable or worth taking; our trunks were split to pieces, and each mean, pitiful wretch crammed his bosom with the contents, which were our apparel, etc., etc., etc.

I ventured to speak to the inhuman monster who had my clothes. I represented to him the times were such we could not replace what they’d taken from us, and begged him to spare me only a suit or two; but I got nothing but a hearty curse for my pains; nay, so far was his callous heart from relenting, that, casting his eyes towards my shoes, “I want them buckles,” said he, and immediately knelt at my feet to take them out, which, while he was busy about, a brother villain, whose enormous mouth extended from ear to ear, bawled out “Shares there, I say; shares.” So they divided my buckles between them. The other wretches were employed in the same manner; they took my sister’s earrings from her ears; hers, and Miss Samuells’s buckles; they demanded her ring from her finger; she pleaded for it, told them it was her wedding ring, and begged they’d let her keep it; but they still demanded it, and, presenting a pistol at her, swore if she did not deliver it immediately, they’d fire. She gave it to them, and, after bundling up all their booty, they mounted their horses. But such despicable figures! Each wretch’s bosom stuffed so full, they appeared to be all afflicted with some dropsical disorder.[4] Had a party of rebels (as they called us) appeared, we should soon have seen their circumference lessen.

They took care to tell us, when they were going away, that they had favored us a great deal—that we might thank our stars it was no worse. But I had forgot to tell you, that, upon their first entering the house, one of them gave my arm such a violent grasp, that he left the print of his thumb and three fingers, in black and blue, which was to be seen, very plainly, for several days after. I showed it to one of our officers, who dined with us, as a specimen of British cruelty. If they call this favor, what must their cruelties be? It must want a name. To be brief, after a few words more, they rode off, and glad was I. “Good riddance of bad rubbish,” and indeed such rubbish was I never in company with before…. After they were gone, I began to be sensible of the danger I’d been in, and the thoughts of the vile men seemed worse (if possible) than their presence; for they came so suddenly up to the house, that I’d no time for thought…. But when they were gone, and I had time to consider, I trembled so with terror, that I could not support myself. I went into the room, threw myself on the bed, and gave way to a violent burst of grief, which seemed to be some relief to my full-swollen heart.

For an hour or two I indulged the most melancholy reflections. The whole world appeared to me as a theater, where nothing was acted but cruelty, bloodshed, and oppression; where neither age nor sex escaped the horrors of injustice and violence; where the lives and property of the innocent and inoffensive were in continual danger, and lawless power ranged at large.

- 1. Major Colin Graham (ca. 1725-1799) led the British Army’s 16th Regiment of Foot Light Infantry Company.

- 2. Lieutenant Morton Wilkinson (ca. 1742-1799)

- 3. Pulled caps: an eighteenth-century expression meaning to quarrel like women, who would pull each other’s caps off in a dispute.

- 4. Dropsical disorder: edema, a condition in which excess fluids collect in the bodily tissue or cavities.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.