Introduction

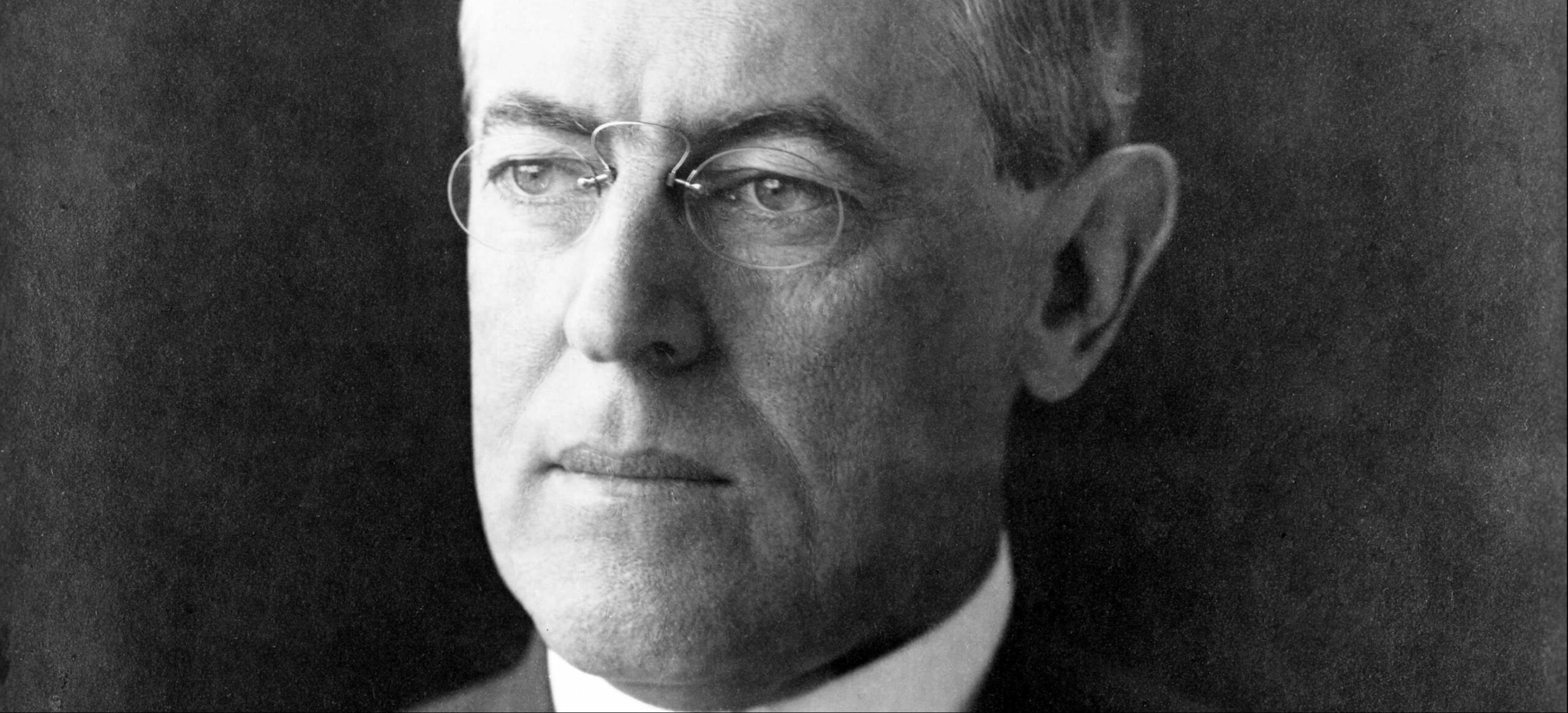

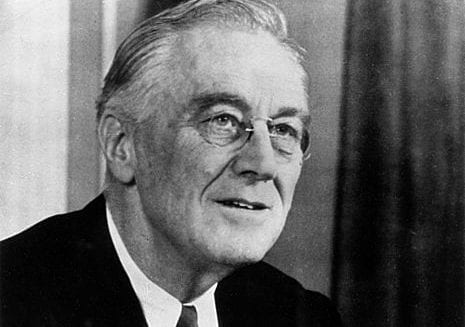

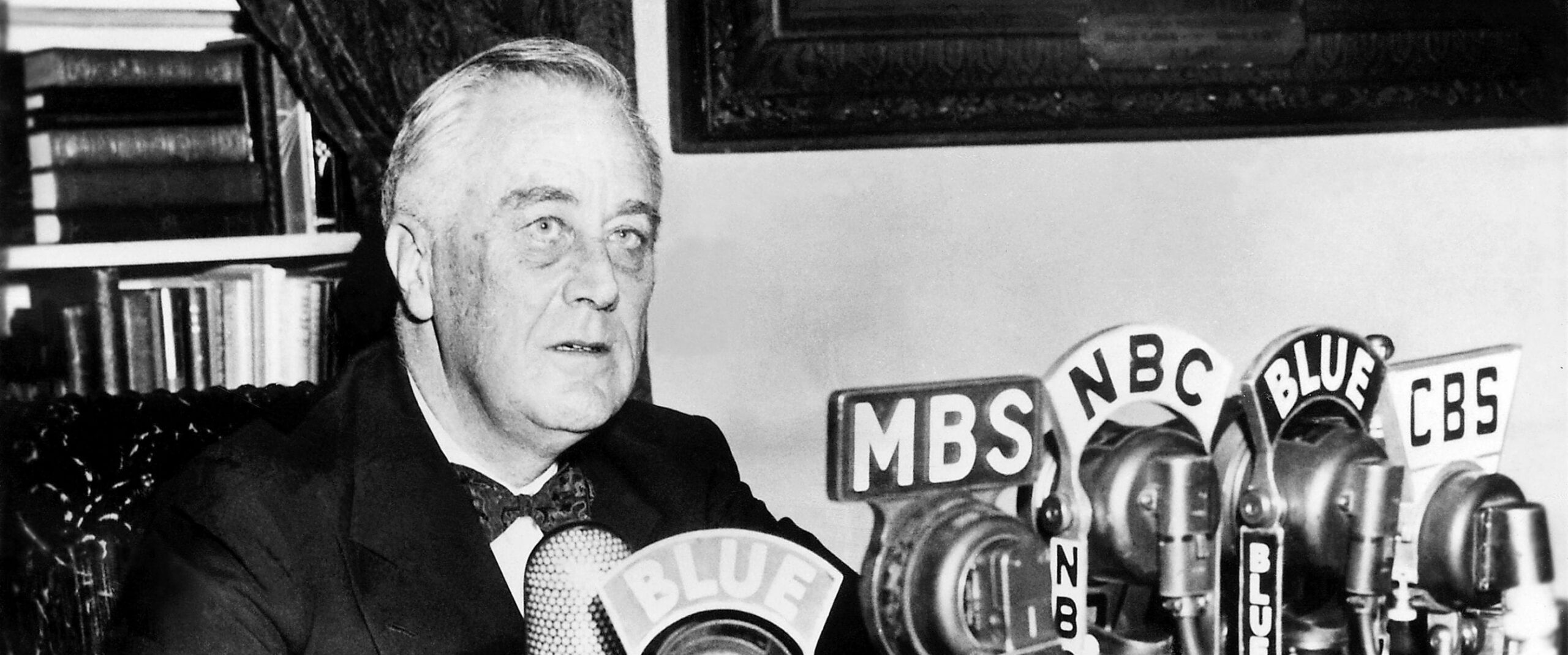

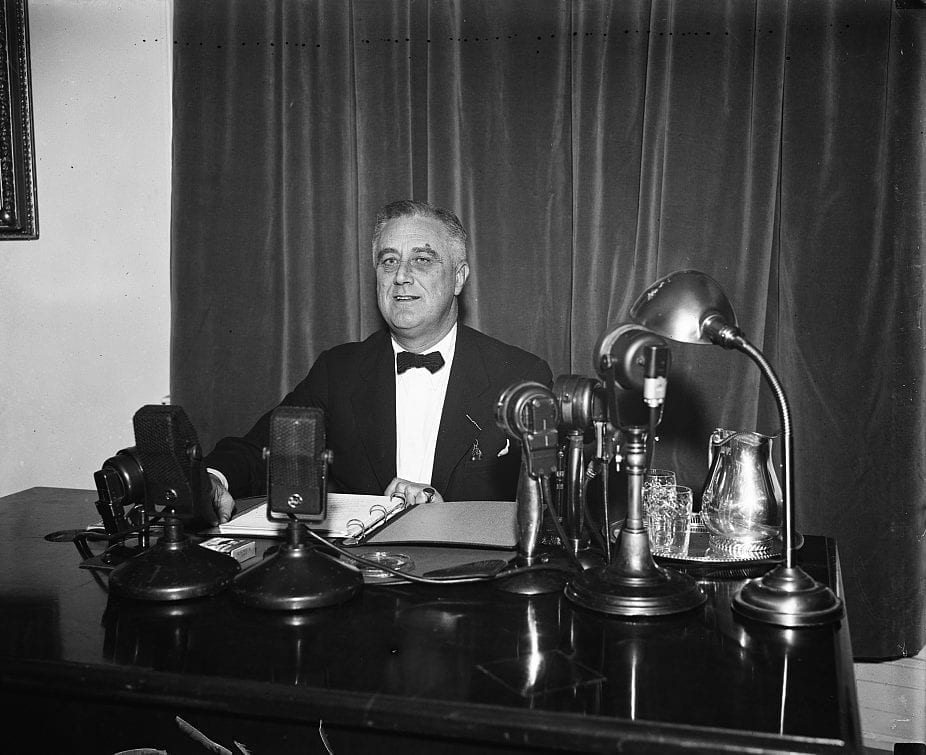

The inauguration of Franklin Roosevelt as president in 1933 marked a change in Indian policy away from allotment (See Annual Message to Congress (1901)), which was meant to assimilate Indians into white culture by making them small-scale farmers. FDR’s Indian New Deal, crafted by Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes (1874–1952) and Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Collier (1884–1968), stressed retention of traditional culture and the self-governance of Native nations, albeit under the supervision of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). A centerpiece of the new policy was the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 (also known as the Wheeler-Howard Act), which permitted Native nations to govern themselves, provided they had a written constitution approved by the BIA.

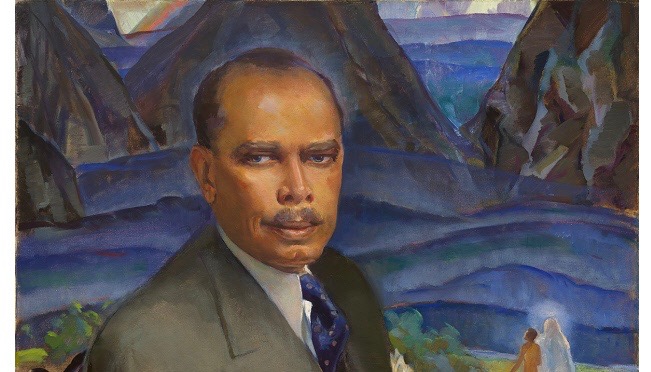

Antonio Luhan (1879–1963) was a Taos Pueblo Indian married to wealthy white socialite and philanthropist Mabel Dodge Luhan (1879–1962). He worked closely with John Collier in promoting the new policy. In this letter to Collier he discussed the difficulties he encountered because Indians were skeptical of a policy that required the BIA’s continued supervision of them.

—Jace Weaver

Mabel Dodge Luhan, Winter in Taos (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1935), 215–220.

Last summer when I went to the Snake Dance, I talked with Fred Kabotie of Chimopavi1 about the Wheeler-Howard Bill.2 He told me then, it was impossible to have an organization, on account of they’re living far apart in separate pueblos. At that time, Fred said that all the old people were against that Bill, and did not believe in it.

This time when I went, on the 15th of November, I went first to Hotevilla3 and I asked how I could arrange to get a meeting to talk about the Wheeler-Howard Bill. They told me to go and see the chief about it for that is all they have—just a chief. I went to see the chief to ask him to have the meeting and he asked me if I had any right to come there and do that kind of work. I hadn’t the recommendation of the agent that day. I just said I had the Bill you sent me, signed John Collier, and I told him, “I am coming from John Collier and he signed this Bill,” and I showed him the sign.

The Chief then told me he would call a meeting for the afternoon.

I went up at two o’clock and there was no sound of any meeting. I went again to the chief and then he began to call the people.

The ones that were there that day came and I explained to them what the Bill meant, and all about Self-Government. . . .

And I told them to look ahead and see that, maybe sometime, some Secretary of the Interior could allot Indian land to separate Indians and pretty soon they would have nothing, but if they decide to have Self-Government under the Wheeler-Howard Bill, they are safe, forever. . . .

I told them that a lot of outsiders would tell them not to take this Bill, for this Bill is no good for white people.

I told them that in past times, the government tried to make white people out of us, and force us into different ways by schools and things, but it looks now they have turned around and are giving us back to our own Indian ways and this Bill helps us to that. But there are still people in the Indian Service who don’t understand this yet, and there are some of those who are against the Bill. And I said, “I know no white man came here and told you this Bill is good, like I come to tell you, who am an Indian, myself.

“I do it because I know all our situation and our religious problem myself. I am not afraid to talk about that to you.

“I have property myself in my pueblo and why should I come here and advise you to take this Bill if it wasn’t any good? I am in the same place as you are. I would be foolish to come here and advise you to take it if it wasn’t any good.”

This is what I said at all the different villages and, of course, I said a lot more things. . . .

At Walapi, they were against the Bill when I got there. At the end of the meeting I had there, they said, “Before you came, we were against the Bill. Our white friends who told us about it, never explained as you have done. We didn’t like this Bill but now we like it.”

At Hotevilla, they just listened to me and said nothing. Then at the end of the meeting, the chief said, “I am going to write to John Collier and ask him all about this.” I said, “All right. Write carefully and make a petition and have your men sign it and John Collier will explain to you better than I do,” I said.

I said, “We have got a real friend in John Collier. He really likes Indians. In past time, we had commissioners against us who tried to stop our ceremony dances and our dances-religious. They nearly destroy us; call our ways bad or immoral or something, and put in the paper they are going to stop us. But John Collier fight for us with the Indian Defense Association and he saves us. Now, he look far ahead and it is like he is putting a wall all around us to protect us—and this Wheeler-Howard Bill is this wall. And no white man or grafter can come inside and take away our land or our religion which are connected together.”

I said, “Otherwise, if we don’t take this Bill, our white neighbors are all around the edge of us, they always look, they always look what they going to see! And maybe, they see gold. They might see coal. And if we had the allotment, the white men might begin to loan money to some Indian boy or girl because they see something on their land. And the boy or girl might want to buy an automobile and will lose their land in a few years because they have borrowed on it. That is enough to finish the Indians. You have no place to hang your hat or shawl. No house, no home. And that all be destroyed.”

I told them now we’re lucky because the president, Mr. Ickes, and the commissioner are all on the side of the Indians. In times to come, maybe, another kind get in and want to go back to the old treatment. But if we have come under the Wheeler-Howard Bill, they cannot get at us and we are safe from them. . . .