Introduction

Raised by religiously indifferent parents, Dorothy Day (1897–1980) had a seeker’s heart that led her to the Episcopal Church as a teenager and then to a flirtation with political radicalism and the bohemian lifestyle in her 20s. After finding herself unexpectedly pregnant in 1925, Day became interested in Catholicism; she and her baby were both baptized in 1927, over the objections of her paramour and the baby’s father, Forster Batterham, an anarchist activist. After Day and Batterham separated, she supported herself as a journalist, taking assignments primarily for Catholic news outlets. This work eventually brought her into contact with Peter Maurin and in 1933, the two co-founded The Catholic Worker. The magazine was intended to make Catholic writing and thought on social justice accessible to a broader audience; in time, it would grow to become much more than a publication—it would serve as the center of gravity for an entire left-wing Catholic movement.

In this statement, Day outlines the theological grounding of her “houses of hospitality” program. Like other “social settlements” (“Religious Education and Contemporary Social Conditions”) these were actual homes in urban communities; unlike most other settlements, the Houses of Hospitality were intensely religious, helping to either deepen the faith of the often-primarily Catholic demographic of their locales, or to convert those who might otherwise feel that God was silent in the midst of their poverty. In 2018, there are over 245 self-proclaimed Catholic Worker communities (most centered around Houses of Hospitality) in cities around the world.

—Sarah A. Morgan Smith

Source: Dorothy Day, “Houses of Hospitality,” The Catholic Worker (December 1936), 4. Courtesy of “The Catholic Worker Movement” website at www.catholicworker.org.

During this last month news comes in that our fellow workers in Rochester, Pittsburgh, and Chicago want to start Houses of Hospitality. Already over in England, the staff of The English Catholic Worker have opened a House. We know the difficulties of the undertaking so it is in place to reiterate some of the principles by which we began our work.

We emphasize again the necessity of smallness. The idea, of course, would be that each Christian, conscious of his duty in the lay apostolate, should take in one of the homeless as an honored guest, remembering Christ’s words,

“Inasmuch as ye have done it unto the least of these, ye have done it unto me.”

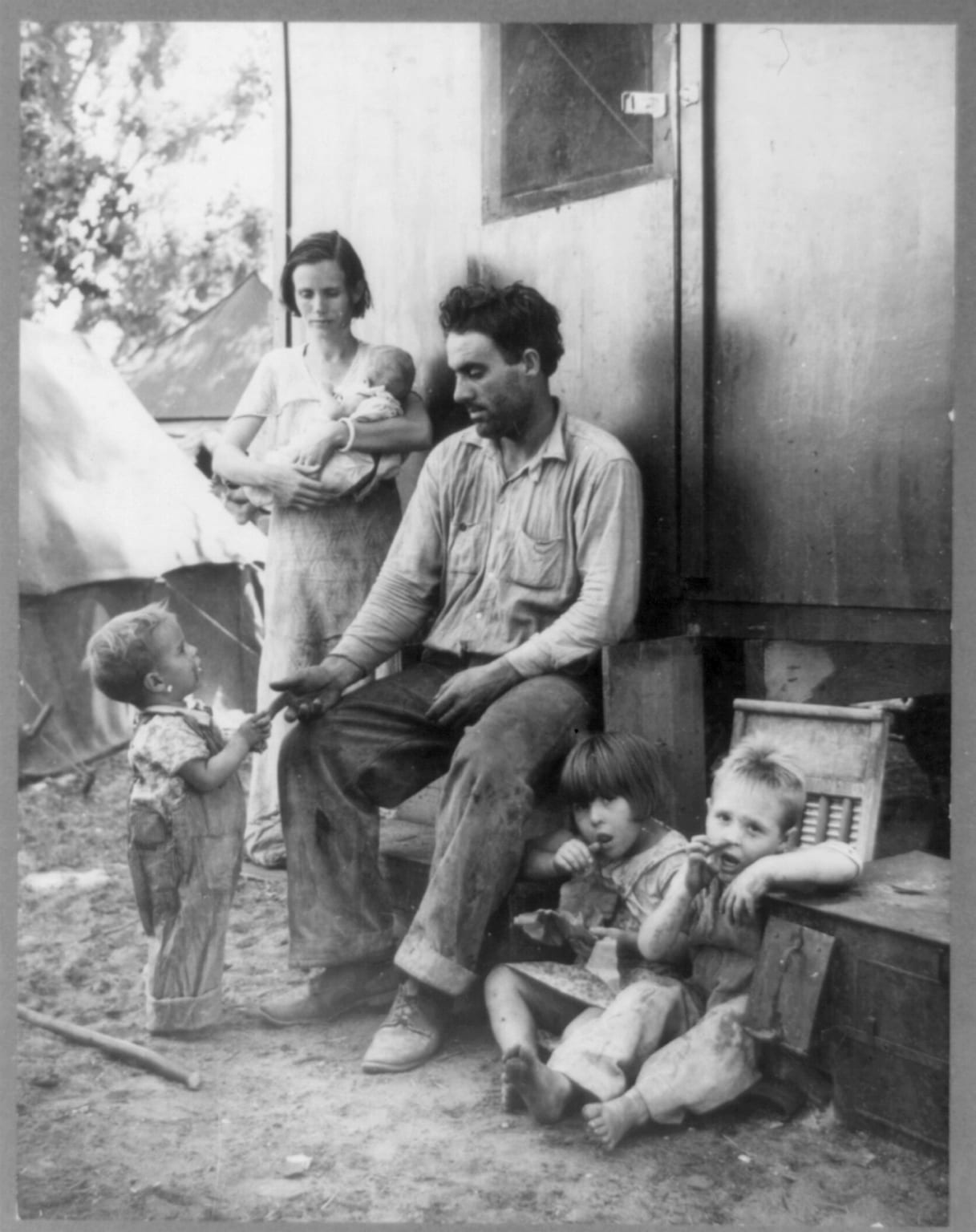

The poor are more conscious of this obligation than those who are comfortably off. We know of any number of cases where families already overburdened and crowded, have taken in orphaned children, homeless aged, poor who were not members of their families but who were akin to them because they were fellow sufferers in this disordered world.

So first of all let us say that those of our readers who are interested in Houses of Hospitality might first of all try to take some one into their homes.

Several of the women workers of our group here in New York who have jobs have moved down to Mott street now and taken little slum apartments and are offering a room and bed and board to our overflow. They are exemplifying perfectly the idea of hospitality.

But if family complications make this impossible, then let our friends keep in mind the small beginnings. I might almost say that it is impossible to do this work unless they themselves are ready to live there with their fellow guests, who soon cease to become guests and become fellow workers. It is necessary, because those who have the ideal in mind, who have the will to make the beginnings, must be the ones who are on hand to guide the work. Otherwise it is just another charity organization, and the homeless might as well go to the missions or municipal lodging houses or breadlines which throughout the depression have become well organized almost as a permanent part of our civilization. And that we certainly do not want to perpetuate.

Cyril Echele, out in St. Louis, is beginning in the right way. Read his letter in this issue of the paper. He is starting with a store and with whatever means come to hand. Clothes, some food, some furniture comes in. He is getting along with what he has, and the work will grow.

We began with a store, went on to an apartment rented in the neighborhood, from thence we moved to a twelve-room house, and now we have twenty-four rooms here in Mott street.

It is not enough to feed and shelter those who come. The work of indoctrination must go on. There must be time for conversations, and what better place than over the supper table? There must be meetings, discussion groups, the distribution of literature. There must be some one always on hand to do whatever comes up, whether that emergency is to go out on a picket line, attend a Communist meeting for the purpose of distributing literature, care for the sick or settle disputes. And there are always arguments and differences of opinion in work of this kind, and it is good that it should be so because it makes for clarification of thought, as Peter says, and cultivates the art of human contacts.

We call attention again to the fact that the Communists have set themselves to do four things, according to the reports of the last meeting of the Third International: to build up anti-war and anti-fascist groups in the colleges; to organize the industrial workers; to start a farm-labor party and to organize the unemployed.

Houses of Hospitality will bring workers and scholars together. They will provide a place for industrial workers to discuss Christian principles of organization as set forth in the encyclicals. They will emphasize personal action, personal responsibility as opposed to political action and state responsibility. They will care for the unemployed and teach principles of cooperation and mutual aid. They will be a half-way house towards farming communes and homesteads.

We have a big program but we warn our fellow workers to keep in mind small beginnings. The smaller the group, the more work is done.

And let us remember, “Unless the Lord build the House, they labor in vain that build it.”