No related resources

Introduction

New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann was one of a number of early-twentieth-century Supreme Court cases that considered whether a state law regulating economic activity violated the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. At issue in this case was an Oklahoma law requiring anyone engaged in manufacturing, selling, and distributing ice to obtain a license from the state corporation commission; the law stipulated that a license would be granted only if it could be shown that increasing the supply of ice was in the public interest and the existing supply was inadequate. Ernest Liebmann lacked a license and challenged the law, arguing that it interfered in an arbitrary fashion with his liberty to engage in the ice business, in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

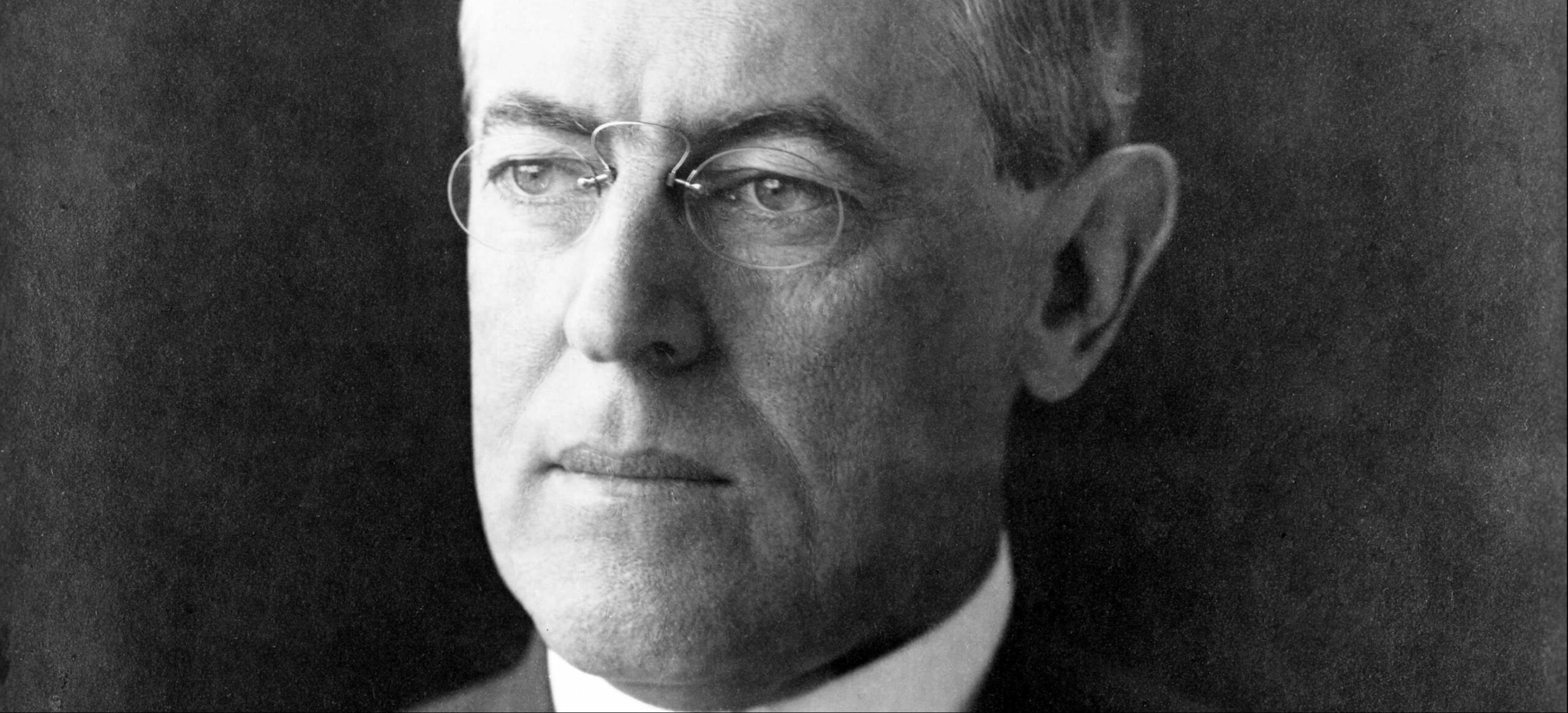

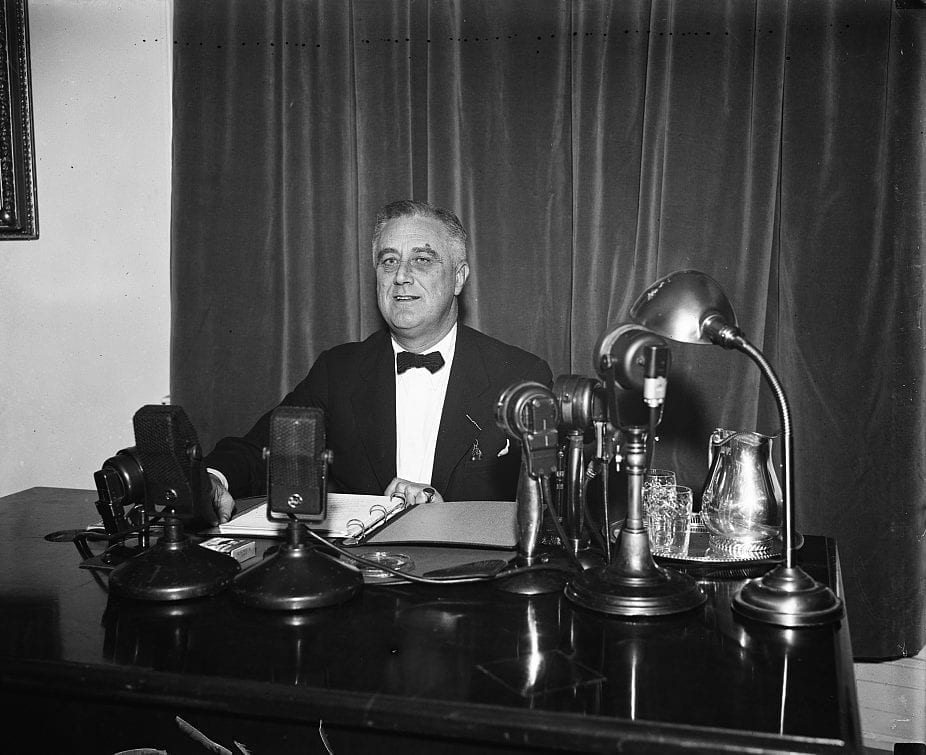

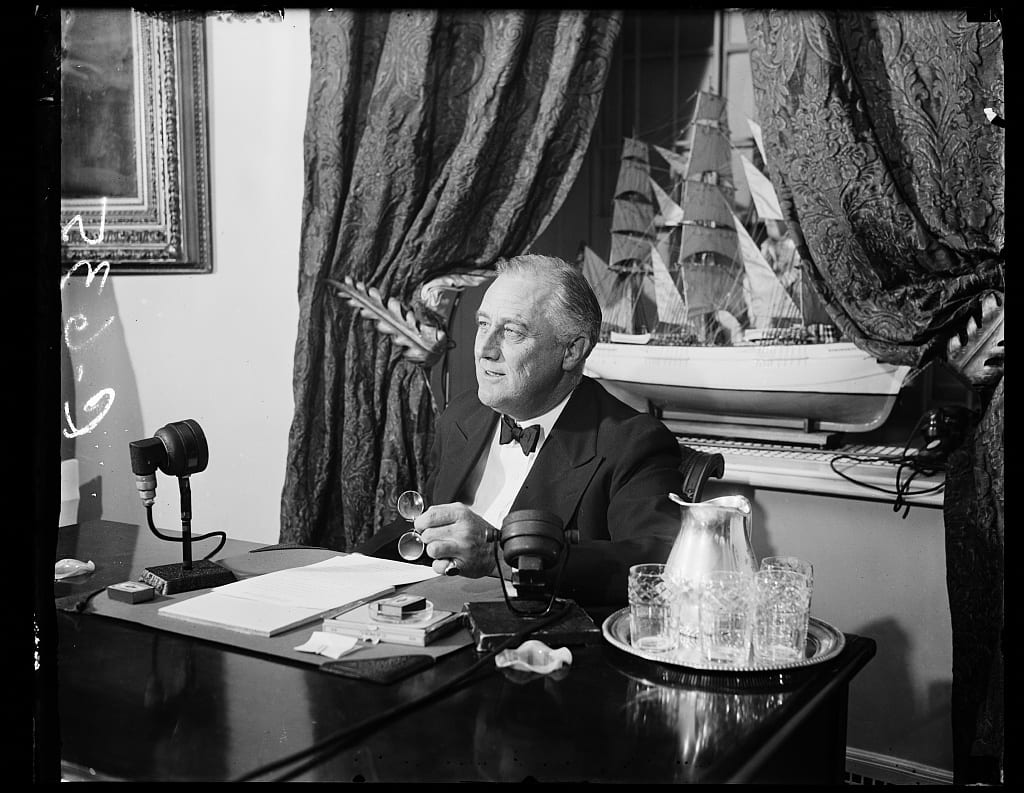

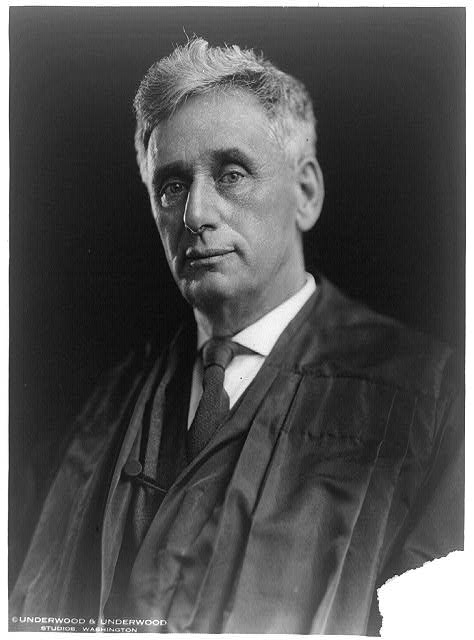

The Supreme Court sided with Liebmann’s challenge and barred enforcement of the Oklahoma law. Justice Louis Brandeis (1856–1941) wrote an oft-quoted dissent to that decision, making an extensive and detailed case that Oklahoma’s law was reasonable and urging the Court to be cautious about limiting state policy discretion. States served as a “laboratory” in which “novel social and economic experiments” could be tried “without risk to the rest of the country.”

Source: 285 U.S. 262, https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/285/262.

Mr. Justice BRANDEIS, dissenting.

Chapter 147 of the Session Laws of Oklahoma 1925, declares that the manufacture of ice for sale and distribution is “a public business”; confers upon the Corporation Commission in respect to it the powers of regulation customarily exercised over public utilities; and provides specifically for securing adequate service. The statute makes it a misdemeanor to engage in the business without a license from the commission; directs that the license shall not issue except pursuant to a prescribed written application, after a formal hearing upon adequate notice both to the community to be served and to the general public, and a showing upon competent evidence, of the necessity “at the place desired”; and it provides that the application may be denied, among other grounds, if “the facts proved at said hearing disclose that the facilities for the manufacture, sale and distribution of ice by some person, firm or corporation already licensed by said commission at said point, community or place, are sufficient to meet the public needs therein.”

Under a license so granted, the New State Ice Company is, and for some years has been, engaged in the manufacture, sale, and distribution of ice at Oklahoma City, and has invested in that business $500,000. While it was so engaged, Liebmann, without having obtained or applied for a license, purchased a parcel of land in that city and commenced the construction thereon of an ice plant for the purpose of entering the business in competition with the plaintiff.1 To enjoin him from doing so this suit was brought by the ice company. Liebmann contends that the manufacture of ice for sale and distribution is not a public business; that it is a private business and, indeed, a common calling; that the right to engage in a common calling is one of the fundamental liberties guaranteed by the due process clause; and that to make his right to engage in that calling dependent upon a finding of public necessity deprives him of liberty and property in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. Upon full hearing the District Court sustained that contention and dismissed the bill. Its decree was affirmed by the Circuit Court of Appeals. The case is here on appeal. In my opinion, the judgment should be reversed....

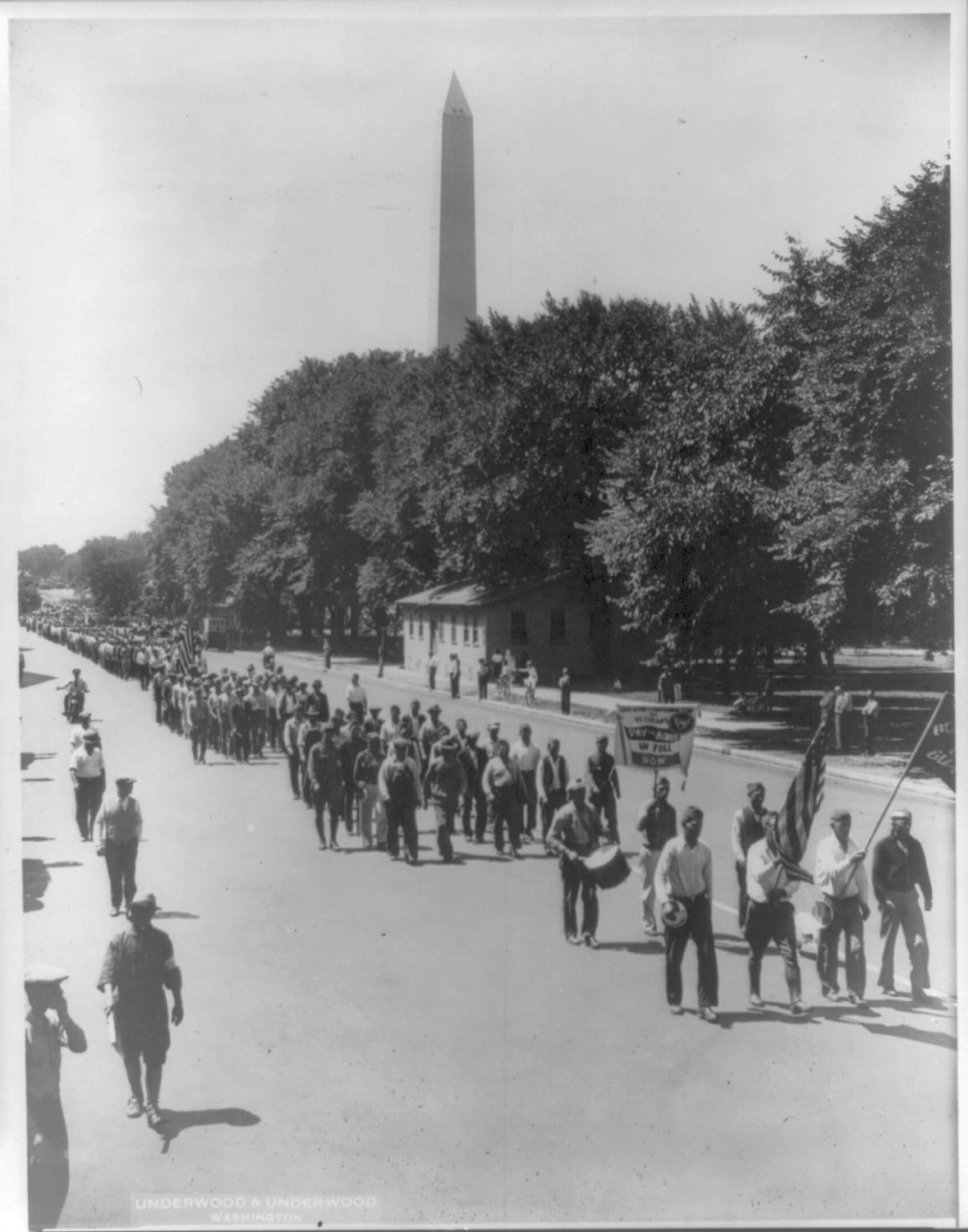

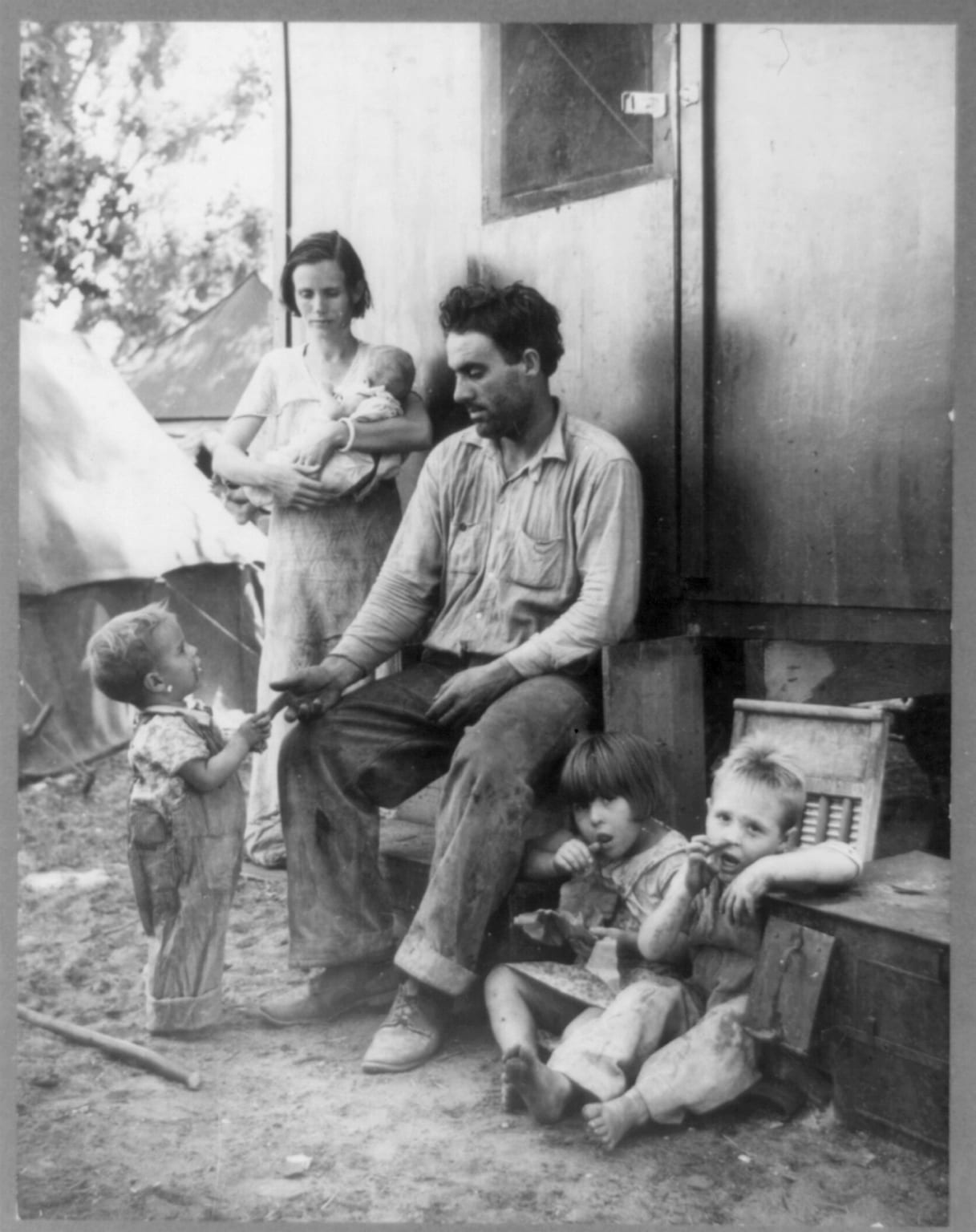

The people of the United States are now confronted with an emergency more serious than war. Misery is widespread, in a time, not of scarcity, but of overabundance. The long-continued depression has brought unprecedented unemployment, a catastrophic fall in commodity prices, and a volume of economic losses which threatens our financial institutions. Some people believe that the existing conditions threaten even the stability of the capitalistic system. Economists are searching for the causes of this disorder and are reexamining the basis of our industrial structure. Businessmen are seeking possible remedies. Most of them realize that failure to distribute widely the profits of industry has been a prime cause of our present plight. But rightly or wrongly, many persons think that one of the major contributing causes has been unbridled competition. Increasingly, doubt is expressed whether it is economically wise, or morally right, that men should be permitted to add to the producing facilities of an industry which is already suffering from overcapacity. In justification of that doubt, men point to the excess capacity of our productive facilities resulting from their vast expansion without corresponding increase in the consumptive capacity of the people. They assert that through improved methods of manufacture, made possible by advances in science and invention and vast accumulation of capital, our industries had become capable of producing from 30 to 100 percent more than was consumed even in days of vaunted prosperity; and that the present capacity will, for a long time, exceed the needs of business. All agree that irregularity in employment—the greatest of our evils—cannot be overcome unless production and consumption are more nearly balanced. Many insist there must be some form of economic control. There are plans for proration.2 There are many proposals for stabilization. And some thoughtful men of wide business experience insist that all projects for stabilization and proration must prove futile unless, in some way, the equivalent of the certificate of public convenience and necessity is made a prerequisite to embarking new capital in an industry in which the capacity already exceeds the production schedules.

Whether that view is sound nobody knows. The objections to the proposal are obvious and grave. The remedy might bring evils worse than the present disease. The obstacles to success seem insuperable. The economic and social sciences are largely uncharted seas. We have been none too successful in the modest essays in economic control already entered upon. The new proposal involves a vast extension of the area of control. Merely to acquire the knowledge essential as a basis for the exercise of this multitude of judgments would be a formidable task; and each of the thousands of these judgments would call for some measure of prophecy. Even more serious are the obstacles to success inherent in the demands which execution of the project would make upon human intelligence and upon the character of men. Man is weak and his judgment is at best fallible.

Yet the advances in the exact sciences and the achievements in invention remind us that the seemingly impossible sometimes happens. There are many men now living who were in the habit of using the age-old expression: “It is as impossible as flying.” The discoveries in physical science, the triumphs in invention, attest the value of the process of trial and error. In large measure, these advances have been due to experimentation. In those fields experimentation has, for two centuries, been not only free but encouraged. Some people assert that our present plight is due, in part, to the limitations set by courts upon experimentation in the fields of social and economic science; and to the discouragement to which proposals for betterment there have been subjected otherwise. There must be power in the states and the nation to remold, through experimentation, our economic practices and institutions to meet changing social and economic needs. I cannot believe that the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment, or the states which ratified it, intended to deprive us of the power to correct the evils of technological unemployment and excess productive capacity which have attended progress in the useful arts.

To stay experimentation in things social and economic is a grave responsibility. Denial of the right to experiment may be fraught with serious consequences to the nation. It is one of the happy incidents of the federal system that a single courageous state may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country. This Court has the power to prevent an experiment. We may strike down the statute which embodies it on the ground that, in our opinion, the measure is arbitrary, capricious, or unreasonable. We have power to do this, because the due process clause has been held by the Court applicable to matters of substantive law as well as to matters of procedure. But, in the exercise of this high power, we must be ever on our guard, lest we erect our prejudices into legal principles. If we would guide by the light of reason, we must let our minds be bold.

The Norris-La Guardia Act

March 23, 1932

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.