No related resources

Introduction

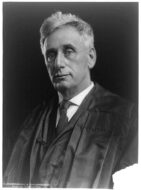

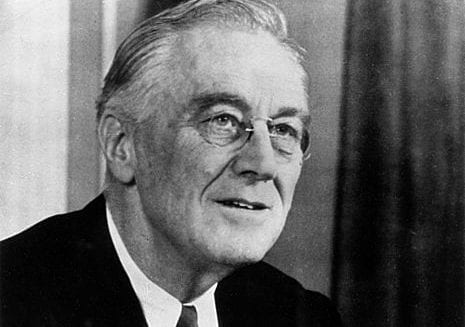

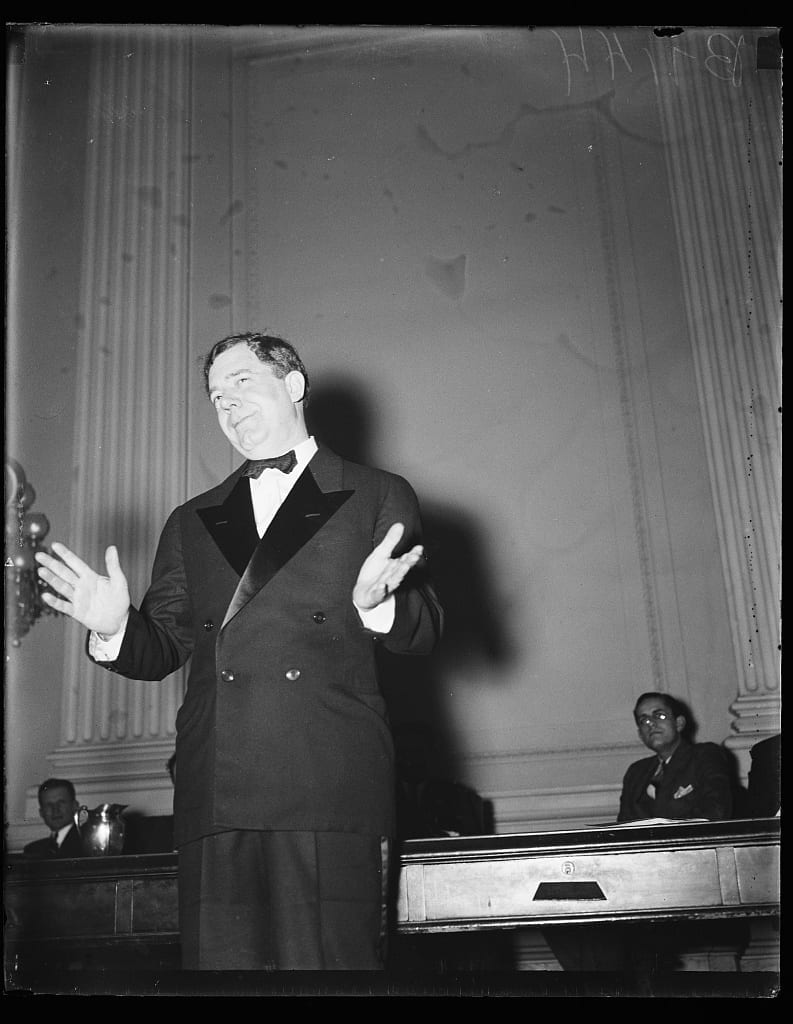

One of the most important pieces of legislation to come out of the Second New Deal originated not with the Roosevelt administration, but with supporters of organized labor in the House and Senate. The impetus for the National Labor Relations Act – sometimes called the Wagner Act after its primary sponsor, Sen. Robert F. Wagner (D-NY) – lay in disillusionment with Section 7(a) of the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) that guaranteed the right of labor to organize (“Fireside Chat” On the Purposes and Foundations of the Recovery Program (1933)). Union leaders complained that many employers simply ignored it, or set up company unions subservient to management. At the same time, labor unrest continued to escalate through 1934, with particularly serious disputes in the trucking, coal mining, textile and shipping industries. One walkout by longshoremen in San Francisco led to a general strike in which thousands of workers throughout the city left their jobs.

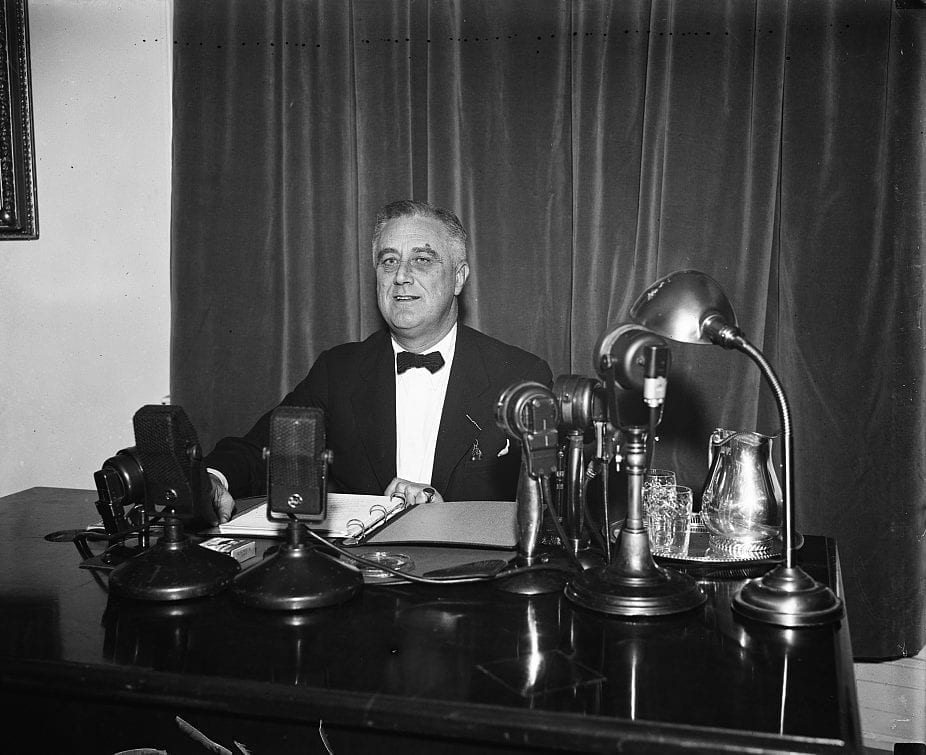

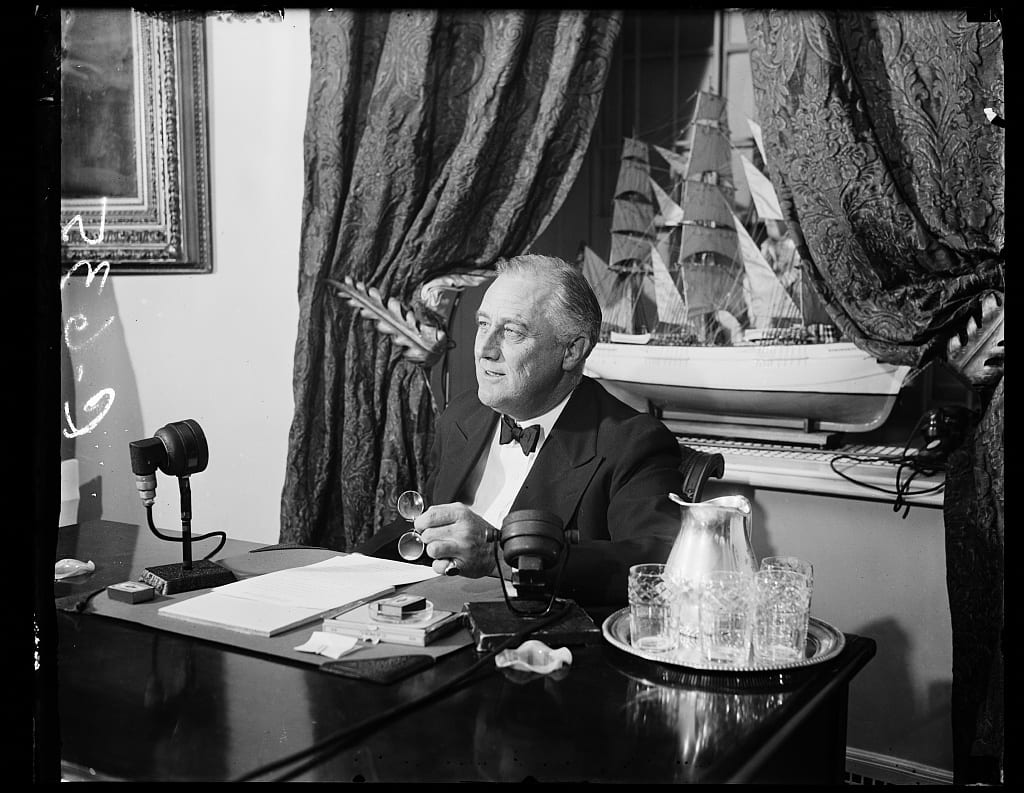

The National Labor Relations Act called for the strengthening of the National Labor Relations Board (originally created under Section 7[a] of the NIRA), empowering that body to mediate labor disputes and enforce its decisions in the courts. The bill also laid out procedures by which workers could choose which union (if any) would represent them, and required that employers bargain in good faith with any union so chosen. Republicans objected, claiming that it would lead to even further labor unrest, and enough southern Democrats joined them that President Roosevelt decided to remain silent on the issue. Two days before the bill came to a vote in the Senate, in fact, he told reporters that he had not “given it any thought one way or the other.” After it passed both houses of Congress, however, the president quickly signed it into law.

Source: Congressional Record, 74th Cong., 1st sess., Vol. 79, pt. 8 (February 21, 1935), pp. 2371-72.

The recovery program has sought to bestow upon the business man and the worker a new freedom to grapple with the great economic challenges of our times. We have released the business man from the undiscriminating enforcement of the antitrust laws, which had been subjecting him to the attacks of the price cutters and wage reducers – the pirates of industry. In order to deal out the equal treatment upon which a just democratic society must rest, we at the same time guaranteed the freedom of action of the worker. In fact, the now famous section 7(a), by stating that employees should be allowed to cooperate among themselves if they desired to do so, merely restated principles that Congress has avowed for half a century.

Congress is familiar with the events of the past 2 years. While industry’s freedom of action has been encouraged until the trade association movement has blanketed the entire country, employees attempting in good faith to exercise their liberties under section 7(a) have met with repeated rebuffs. It was to check this evil that the President in his wisdom created the National Labor Board in August 1933, out of which has emerged the present National Labor Relations Board.

The Board has performed a marvelous service in composing disputes and sending millions of workers back to their jobs upon terms beneficial to every interest. But it was handicapped from the beginning, and it is gradually but surely losing its effectiveness, because of the practical inability to enforce its decisions. At present it may refer its findings to the National Recovery Administration1 and await some action by that agency, such as the removal of the Blue Eagle. We all know that the entire enforcement procedure of the N.R.A. is closely interlinked with the voluntary spirit of the codes. Business in the large is allowed to police itself through the code authorities. This voluntarism is without question admirable in respect to provisions for fair competition that have been written by industry and with which business is in complete accord. But it is wholly unadapted to the enforcement of a specific law of Congress which becomes a crucial issue only in those very cases where it is opposed by the guiding spirits of the code authorities. Secondly, the Board may refer a case to the Department of Justice. But since the Board has no power to subpoena records or witnesses, its hearings are largely ex parte2 and its records so infirm that the Department of Justice is usually unable to act. Finally, the existence of numerous industrial boards whose interpretations of section 7(a) are not subject to the coordinating influence of a supreme National Labor Relations Board, is creating a maze of confusion and contradictions. While there is a different code for each trade, there is only one section 7(a), and no definite law written by Congress can mean something different in each industry. These difficulties are reducing section 7(a) to a sham and a delusion.

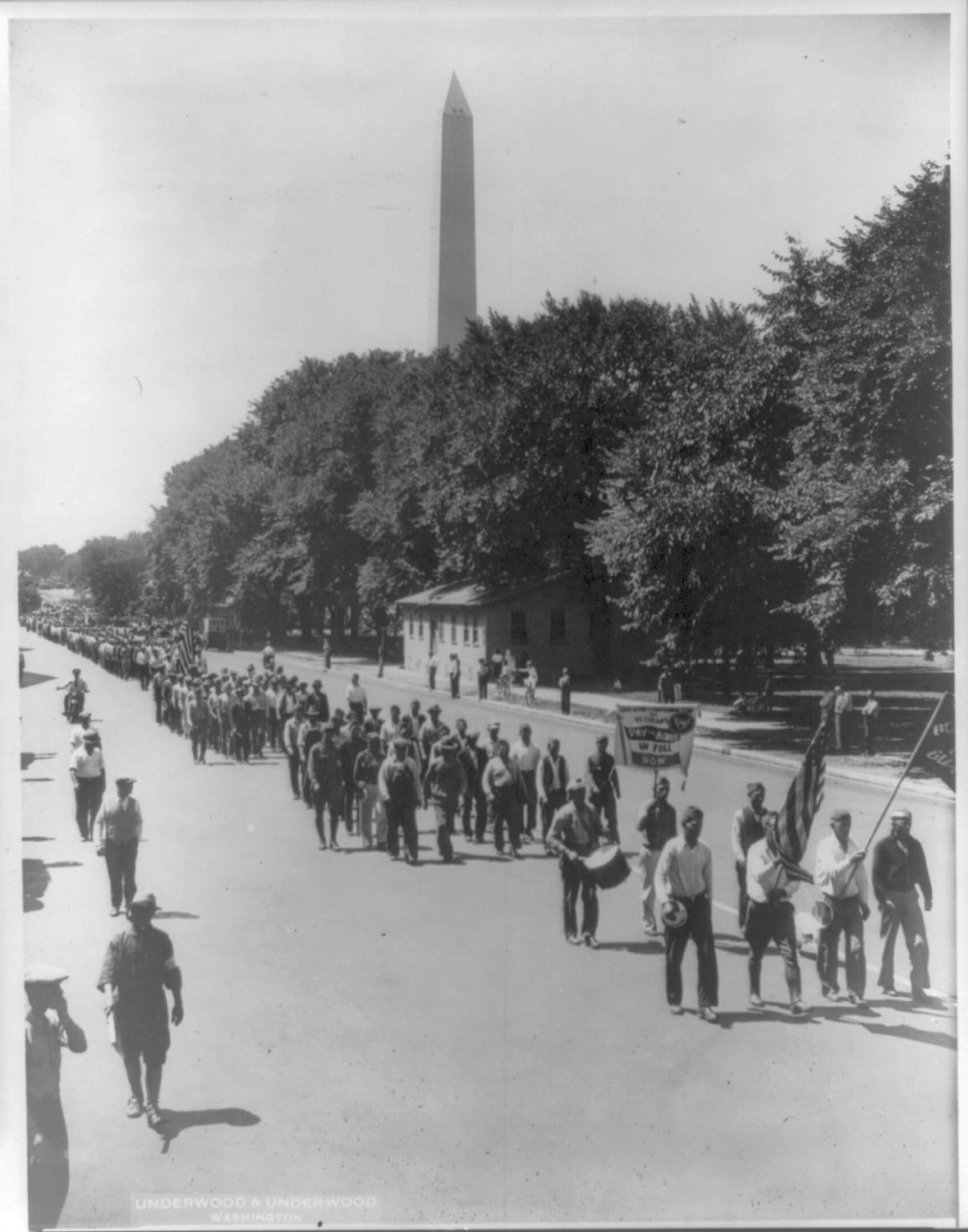

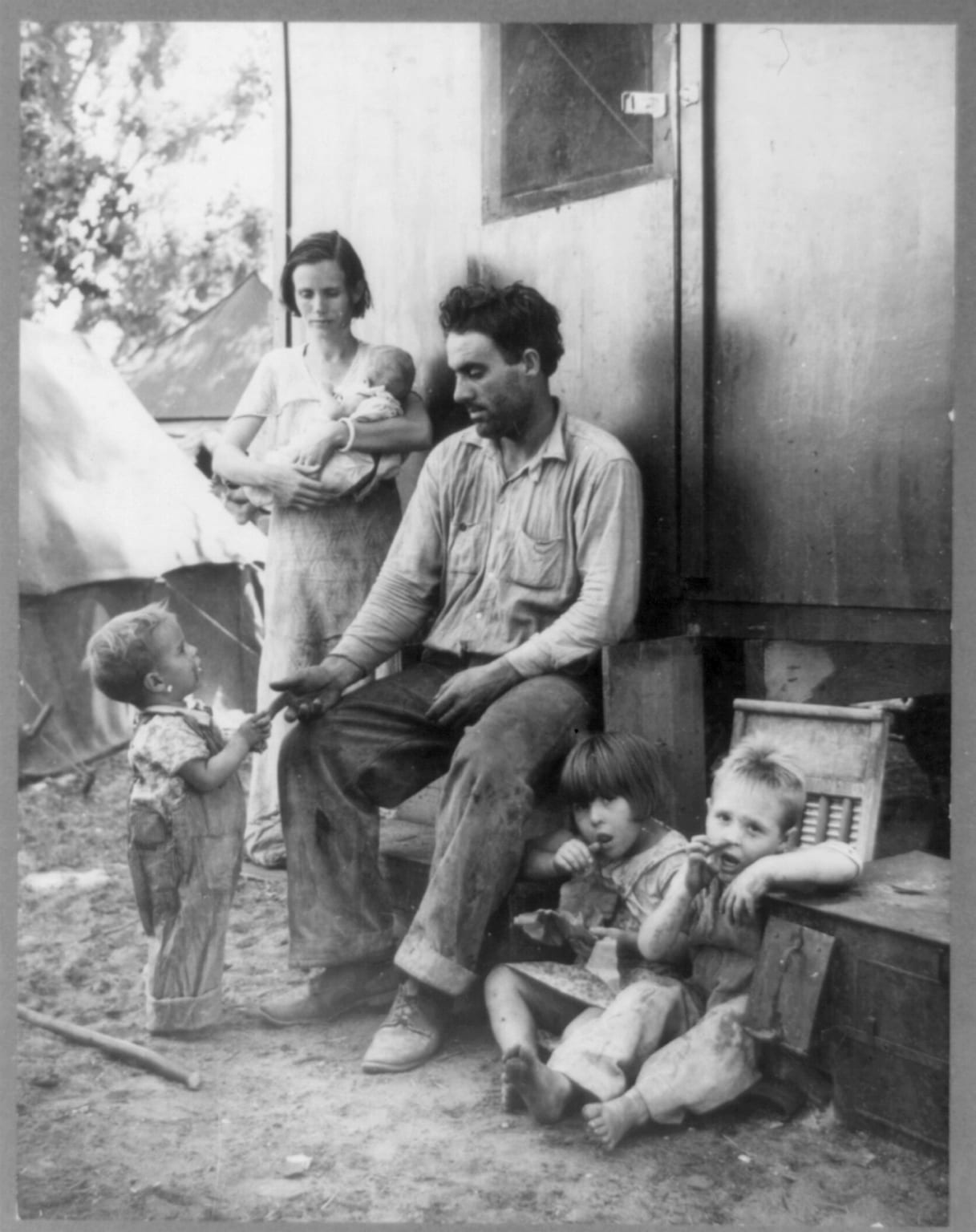

The break-down of section 7(a) brings results equally disastrous to industry and to labor. Last summer it led to a procession of bloody and costly strikes, which in some cases swelled almost to the magnitude of national emergencies. It is not material at this time to inquire where the balance of right and wrong rested in respect to these various controversies. If it is true that employees find it difficult to remain acquiescent when they lose the main privilege promised them by the Recovery Act, it is equally true that employers are tremendously handicapped when it is impossible to determine exactly what their rights are. Everybody needs a law that is precise and certain.

There has been a second and even more serious consequence of the break-down of section 7(a). When employees are denied the freedom to act in concert even when they desire to do so, they cannot exercise a restraining influence upon the wayward members of their own groups, and they cannot participate in our national endeavor to coordinate production and purchasing power. The consequences are already visible in the widening gap between wages and profits. If these consequences are allowed to produce their full harvest, the whole country will suffer from a new economic decline.

The national labor relations bill which I now propose is novel neither in philosophy nor in content. It creates no new substantive rights. It merely provides that employees, if they desire to do so, shall be free to organize for their mutual protection or benefit. Quite aside from section 7(a), this principle has been embodied in the Norris-LaGuardia Act,3 in amendments to the Railway Labor Act4 passed last year, and in a long train of other enactments of Congress.

There is not a scintilla of truth in the wide-spread propaganda to the effect that this bill would tend to create a so-called “labor dictatorship.” It does not encourage national unionism. It does not favor any particular union. It does not display any preference toward craft or industrial organizations. Most important of all, it does not force or even counsel any employee to join any union if he prefers to deal directly or individually with his employers. It seeks merely to make the worker a free man in the economic as well as the political field. Certainly the preservation of long-recognized fundamental rights is the only basis for frank and friendly relations in industry.

The erroneous impression that the bill expresses a bias for some particular form of union organization probably arises because it outlaws the company-dominated union. Let me emphasize that nothing in the measure discourages employees from uniting on an independent- or company-union basis, if by these terms we mean simply an organization confined to the limits of one plant or one employer. Nothing in the bill prevents employers from maintaining free and direct relations with their workers or from participating in group insurance, mutual welfare, pension systems, and other such activities. The only prohibition is against the sham or dummy union which is dominated by the employer, which is supported by the employers, which cannot change its rules or regulations without his consent, and which cannot live except by the grace of the employer’s whims. To say that that kind of a union must be preserved in order to give employees freedom of selection is a contradiction in terms. There can be no freedom in an atmosphere of bondage. No organization can be free to represent the workers when it is the mere creature of the employer.

Equally erroneous is the belief that the bill creates a closed shop for all industry. It does not force any employer to make a closed-shop agreement.5 It does not even state that Congress favors the policy of the closed shop. It merely provides that employers and employees may voluntarily make closed-shop agreements in any State where they are now legal. Far from suggesting a change, it merely preserves the status quo.

A great deal of interest centers around the question of majority rule. The national labor relations bill provides that representatives selected by the majority of employees in an appropriate unit shall represent all the employees within that unit for the purposes of collective bargaining. This does not imply that an employee who is not a member of the majority group can be forced to enter the union which the majority favors. It means simply that the majority may decide who are to be the spokesmen for all in making agreements concerning wages, hours, and other conditions of employment. Once such agreements are made the bill provides that their terms must be applied without favor or discrimination to all employees. These provisions conform to the democratic procedure that is followed in every business and in our governmental life, and that was embodied by Congress in the Railway Labor Act last year. Without them the phrase “collective bargaining” is devoid of meaning, and the very few unfair employers are encouraged to divide their workers against themselves.

Finally, the National Labor Relations Board is established permanently, with jurisdiction over other boards dealing with cases under section 7(a) or under its equivalent as written into this bill. Nothing could be more unfounded than the charges that the Board would be invested with arbitrary or dictatorial or even unusual powers. Its powers are modeled upon those of the Federal Trade Commission6 and numerous other governmental agencies. Its orders would be enforceable not by the Board, but by recourse to the courts of the United States, with every affected party entitled to all the safeguards of appeal.

The enactment of this measure will clarify the industrial atmosphere and reduce the likelihood of another conflagration of strife such as we witnessed last summer. It will stabilize and improve business by laying the foundations for the amity and fair dealing upon which permanent progress must rest. It will give notice to all that the solemn pledge made by Congress when it enacted section 7(a) cannot be ignored with impunity, and that a cardinal principle of the new deal for all and not some of our people is going to be supported and preserved by the Government.

- 1. Established by the National Industrial Recovery Act (Document 19) in 1933, the National Recovery Administration sought to coordinate the activities of labor, industry and government through voluntary codes to reduce what the Roosevelt administration thought was inefficient competition. Its symbol was a blue eagle. The Supreme Court ruled the NRA unconstitutional in 1935 (Document 28).

- 2. A legal term referring to a court procedure at which all concerned parties are not present.

- 3. Passed in 1932, this act gave certain protections to labor unions and those trying to organize them.

- 4. Passed in 1926 and amended in 1934, this act encouraged the resolution of labor disputes through mediation.

- 5. An agreement between union and management mandating that new employees join the union as a condition of employment.

- 6. Established in 1914, the Commission seeks to prevent anti-competitive business practices, such as monopolies.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.