No related resources

Introduction

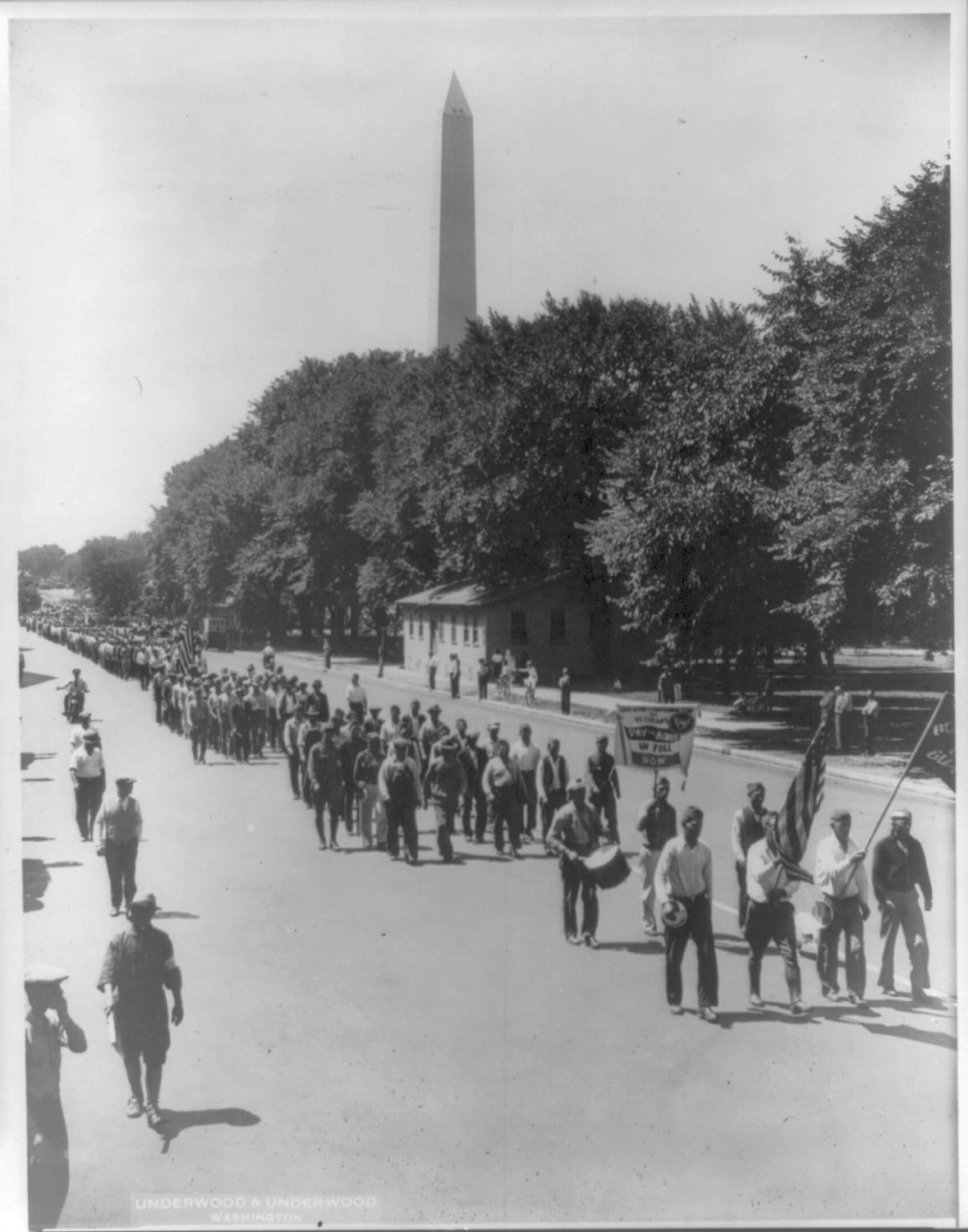

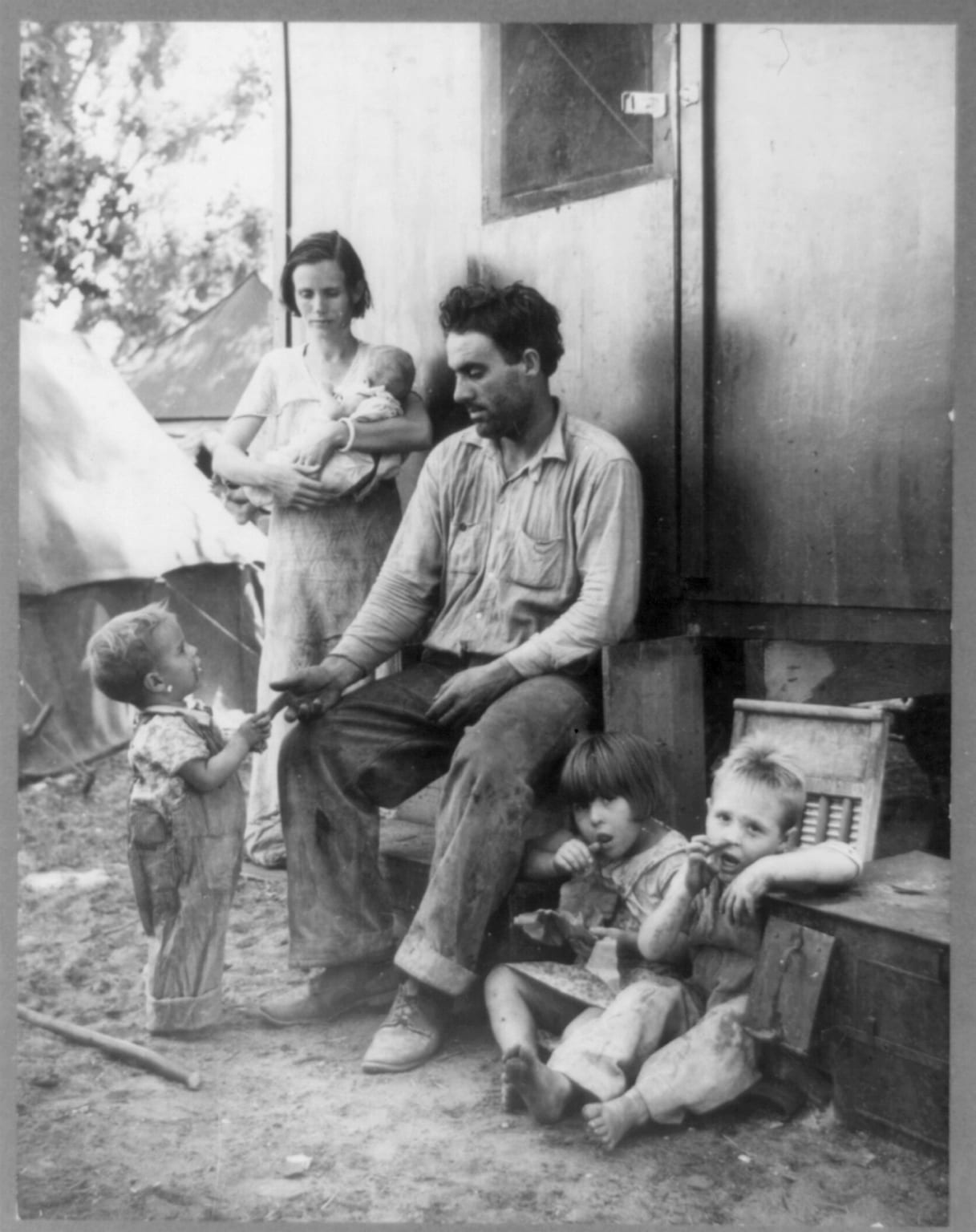

The United Automobile Workers’ union formed in 1935 as part of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), and after some initial success in organizing workers at small factories, decided to take on the industry’s largest employer, General Motors. When GM refused to recognize the union, workers went on strike at a GM plant in Flint, Michigan, on December 30, 1936. This was unlike ordinary strikes, however, in which workers picketed outside and tried to prevent replacement workers from entering; instead they engaged in a “sit-down” strike, physically occupying the facility and refusing to allow anyone else inside. When judges issued injunctions ordering the workers to vacate the premises, they were simply ignored. When police tried to force their way in the strikers hurled metal objects on them, forcing them to withdraw. The strike quickly spread to a number of other GM plants, bringing production to a virtual halt. The left-wing journal The Nation published this highly sympathetic account of the strike’s opening days.

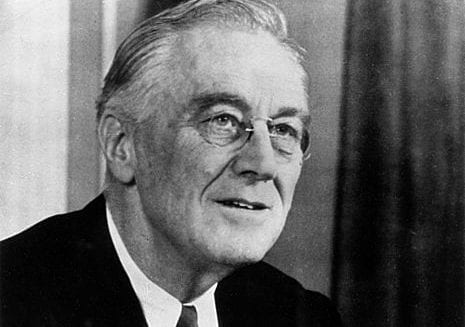

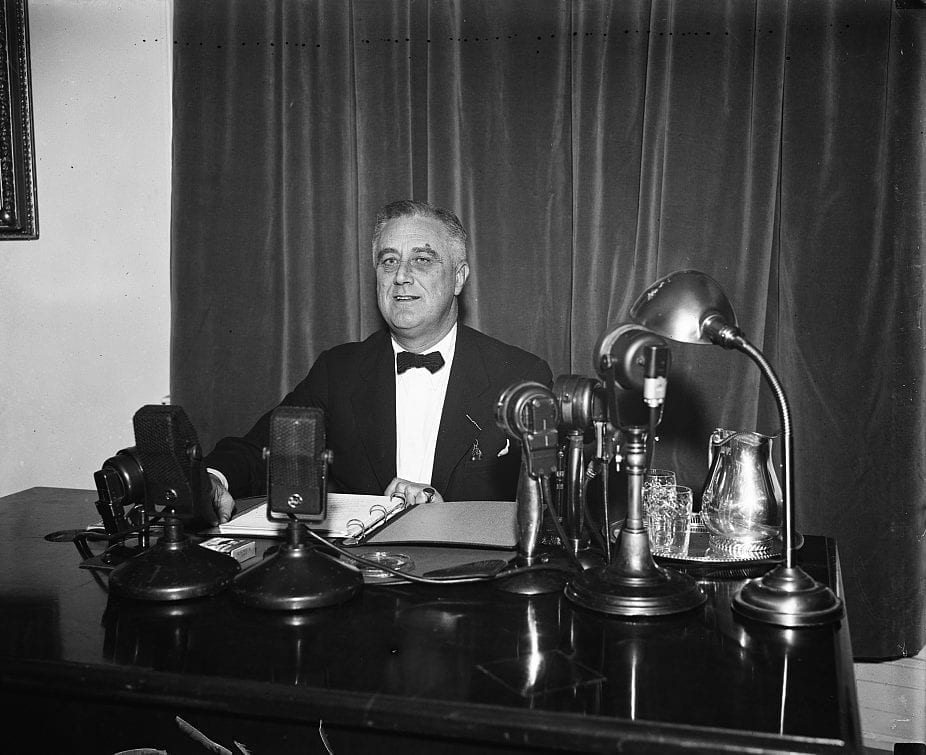

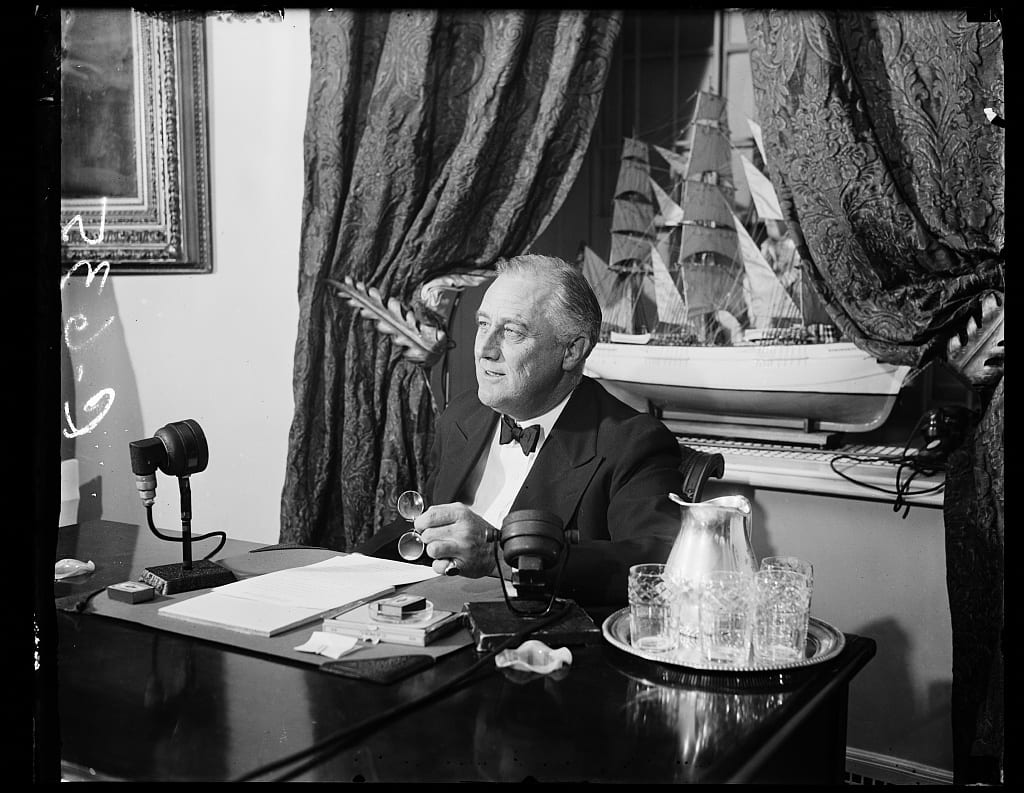

The “sit-down” strike posed a political problem for the Roosevelt administration. A Gallup poll showed that a solid majority of Americans opposed the tactic, and even to many in the labor movement (particularly the more conservative “craft unions” of the American Federation of Labor) it appeared dangerously radical. However, the president understood how important support from the CIO had been to his recent successful reelection bid. Therefore, even though Vice President John Nance Garner urged Roosevelt to use federal troops to break the strike, the president instead called upon General Motors to recognize the UAW. GM finally did so on February 11, 1937. Practically overnight the United Automobile Workers became one of the most powerful labor organizations in the country.

Source: The Nation 144:3 (January 16, 1937), pp. 64-66. Available online from The Social Welfare History Project (Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries). http://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/eras/great-depression/detroit-digs-1937/

The future of the Committee for Industrial Organization, [the] most hopeful development in the history of the American labor movement, lies in the hands of the sitdown strikers who have occupied Fisher Body Plant No. 1 at Flint, Michigan.

The sitdowners tell the story in the simple verses of their homespun “Song of the Fisher Body Strike.” The dies,1 key to most of General Motors production, had been loaded on a railroad car in the plant yard. They were to be shipped to some less strong union center, possibly Pontiac. “When the dies they started moving, the union men they had a meeting to decide right then and there what must be done,” says the song, chanted in nasal tones to the tune of “The Martins and the Coys.”2 And, “When they loaded up a box-car full of dies, the union boys they stopped them, and the railroad workers backed them. . . .”

Now they really started out to strike in earnest,

They took possession of the gates and buildings too.

They placed a guard in either clockhouse,

Just to keep the non-union men out,

And they took the keys and locked the gates up, too.

The attempt to move the dies was regarded by the International union, the United Automobile Workers of America, as a breach of faith. The plant was occupied on December 30. On the previous Tuesday a union committee had submitted demands and asked for a reply by the following Monday. The management’s answer was to load the dies on the box-car. Although strikes were already in effect in Atlanta, Kansas City, and Cleveland, the International union had not intended as yet to force the issue on a national scale. But General Motors in Fisher Body No. 1 at Flint provided the spark. Fisher Body No. 2 at Flint followed No. 1 on strike, and walkouts, sitdowns, or both followed in Norwood (Ohio), Anderson (Indiana), Janesville (Wisconsin), Kansas City, Toledo, and Detroit. Helpless, General Motors was forced to shut down additional plants in Anderson, Atlanta, Bay City, Dayton, Flint, Kansas City, Muncie, Saginaw, and Detroit. Today 88,000 General Motors employees are out.

Attention has been shifted from the scattered front-line trenches to union and corporation general headquarters in Detroit. The first week of the strike has been marked by the total failure of peace efforts; the negotiations have served chiefly to clarify the issues in the conflict and to reveal the determination of both sides. The union is ready now to sit down and bargain for an agreement. The corporation insists, however, that the five occupied plants – in Flint, Cleveland, Detroit, and Anderson – must first be evacuated. In other words, they are asking the union to surrender its arms and then resume the war.

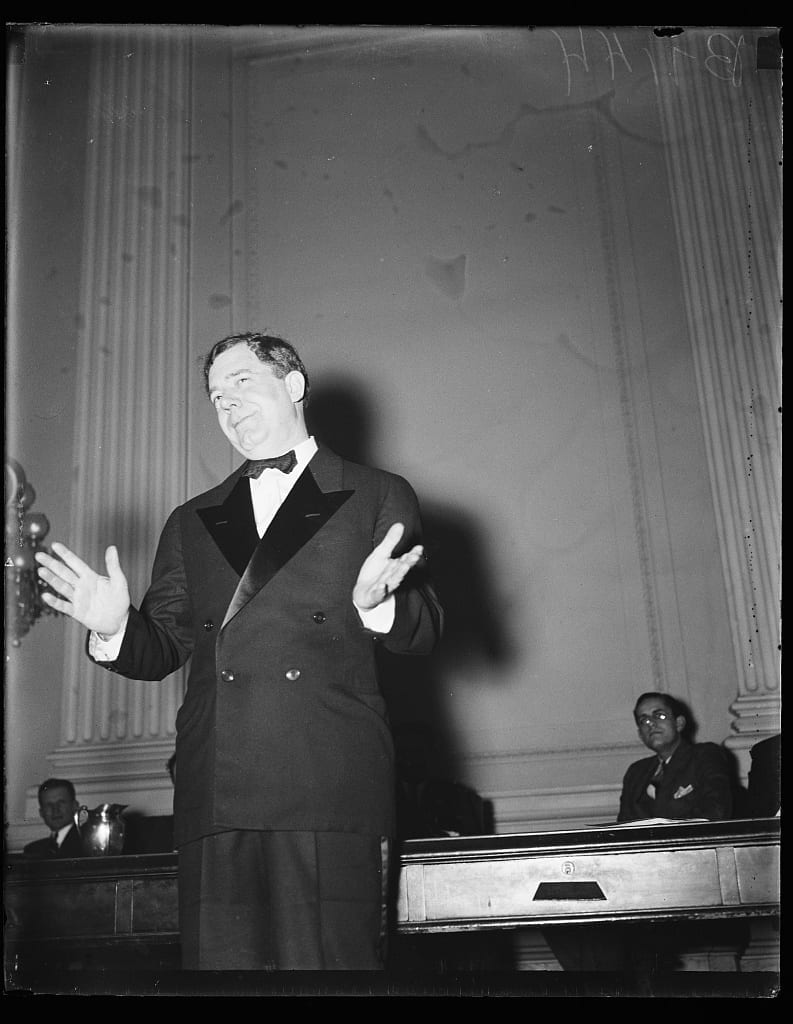

The union does not take time to make any theoretical defense of its right to hold the factories. They say they will not surrender to the corporation the dies and sixty-day supply of glass now in Fisher Body No. 1 at Flint, and that they will not march out of the plants so that professional strike-breakers and thug guards may walk in. Homer Martin, president of the union, declares the sitdowners have found a heavy supply of tear gas and other equipment of war in the plants. Under the circumstances the union feels that law and peace are in its keeping. It is taking scrupulous care of the machinery.

That General Motors wants evacuation of the plants only to gain an advantage in a resumption of the war is obvious. The corporation insists it will grant none of the union demands. It says it will “recognize” the union – along with company unions – for collective-bargaining purposes, but will not grant recognition of the union as the sole bargaining agency. For the sake of getting down to peace talks, the union has agreed to waive its demand for exclusive recognition before a conference, but it is asking for other guaranties before it will withdraw the sitdowners. The workers ask that no dies be moved, that vigilante movements and circulation of synthetic employee “loyalty” pledges be ended, that the Flint injunction – obtained from a judge who had 1,000 shares of General Motors stock tucked away in his judicial robes – be vacated, and that negotiations be started on a national basis. To this, William S. Knudsen, executive vice-president of General Motors, has given a flat no. According to its memorandum to Governor Frank Murphy, dogged but unsuccessful seeker of peace, the corporation will not even agree to bargain for a national agreement.

General Motors must have known it was making an offer which the union could not consider without inviting a repetition of the collapse of the 1934 strike.3 While talking peace to Governor Murphy it has thrown up breastworks for a fight to the end.

First-line attacks of the corporation have taken the form of sponsoring vigilante movements. These have come to the surface in both Flint and Saginaw. In Flint an “Alliance for Security of Our Jobs, Our Homes, and Our Community” has come into existence. It is headed by a former paymaster at the Buick plant and a former mayor of Flint, George E. Boysen. This gentleman insists he is financing the “alliance” from his own pocket. Its strategy has been to enroll as members automobile workers who wish to return to work. Mr. Boysen has variously estimated the membership of the “alliance” at 2,000, 5,000, and 12,000, but he called off a parade planned for Saturday night rather than display the weakness of the movement. The headquarters of the alliance on the main Flint thoroughfare were dark and closed early Saturday evening, while hundreds of citizens patrolled the street. The reporters who have flocked to Flint find Mr. Boysen something of a crackpot.

But all this does not mean that the Flint Alliance has folded up. The technique of these “spontaneous” movements of loyal home folk has always been to depend on outside thugs as ringleaders. The strategy has been outlined by the ebullient Pearl L. Bergoff,4 who planned it to combat the Akron rubber strike that threatened in 1935. “It was going to be a new idea,” said the Red Demon. “No more imported strike-breakers, just local people doing the job.” But the nucleus of the “local people,” he added, was to be four or five hundred imported mercenaries. To meet the threat of the Flint Alliance, several hundred automobile strikers from other cities are camped in Flint, and hundreds more are available on a few hours’ call. The discipline of the strikers is remarkable. Company agents tried to incite a riot Thursday night, when they smashed a strikers’ loud-speaker and a meeting near union headquarters, but the riots they hoped to stage did not develop. The sitdown strike leaders tell of other provocation. They have a strict rule that no liquor is to be brought into the occupied plant, and the only time the rule was violated, they say, was on New Years Eve when they permitted some company foremen to enter the plant. Since then there has been no drinking and no foreman has been allowed “to snoop around” among the men.

The other leading practice of the corporation has been to stir up resentment against the union and intimidate its employees by circulation of “loyalty” pledges. Many of these are distributed by mail with return post cards enclosed. The entire method is devised to frighten strikers with threats of a black list. Some workers who have refused to sign have been discharged outright. By now the petitions have become worthless, except to provide headlines for the kept press. Union leaders have told the workers to go ahead and sign them and then forget about them.

To buttress these pressures, the Flint Journal, which is virtually a company organ, displays on its first page a three-column picture of police armed with clubs, tears-gas guns, gas masks, bullet-proof vests, ammunition, and clubs. The papers of the smaller cities, such as the Flint Journal and the Saginaw News, are abject in their crawling before the corporation. The metropolitan press is less crude. Detroit’s papers pathetically feature unsubstantiated peace reports, hoping against hope that there will not be a long conflict in which they may be forced to take sides. The Detroit News did not print the impeachment demand filed against Judge Black of Flint or the union’s revelations of his ownership of General Motors stock until these things were no longer news. The Detroit Free Press refers to the alleged imminent return to work of employees as “hopeful news.” The Cleveland Press headlines Wyndham Mortimer, vice-president of the union and resident of Cleveland for twenty-six years, as an “outside agitator.” On the whole, the fault is not with the correspondents on the scene. There are distinctive examples of impartiality and an understanding of the forces at work on both sides. One of these, it is pleasant to report, is the Chicago Daily News. Another fine piece of reporting was the account of the Flint Fisher Body No. 1 sitdown published in New York’s Daily News. Passing from the lofty stability of the General Motors building in Detroit to the tense but calm offices of the baby union which has tied up the giant corporation, one thinks constantly of the men in Flint’s Fisher Body Plant No. 1. Police and kitchen committees, runners to the union headquarters, strike and executive committees, and a general assembly every afternoon at four have placed the destiny of the strike in the hands of the rank and file. Leaders are verbally slow but mentally clear. Rank-and-file cooperation has made the “chief of police” the best loved man in the plant. There is no grumbling, although the men have been in the plant for eleven days and nights. Wives come to the windows to pass in laundry and food, which goes immediately into the general commissary. Women may not enter, but children may be passed through the windows for brief visits with their fathers. Every night at eight the strikers’ band of three guitars, a violin, a mouth organ, and a squeeze box broadcast over a loud-speaker for the strikers and the women and children outside. Spirituals and hill-billy songs fill out the program, which closes with “Solidarity Forever.”5

P. S. I forgot to mention the American Federation of Labor, an easy thing to do these days. It has no members to speak of in the automobile plants, although John P. Frey6 undertook to order his followers back to work. The craft unions have no contracts with General Motors. Their leaders’ telegrams supporting the corporation against the strikers was a piece of work worthy of a feeble-minded Judas. The move has turned out to be a boomerang. The strikers are comforted by the fact that the A. F. of L. is openly against them and not among their supposed friends, where it would be in a position to attempt a more damaging betrayal, as in 1934.7

- 1. molds for forming metal

- 2. The “Martins and the Coys” was a novelty song popular in 1936 that imitated traditional country music, referred to later in the document as “hill-billy songs.”

- 3. Passage of the National Industrial Recovery Act (1933; see Roosevelt's Fireside Chat On the Purposes and Foundations of the Recovery Program) spurred labor organizing, which led to numerous strikes in 1934, including in the automobile industry, several of which were violent.

- 4. Bergoff (1876–1947) was a professional strikebreaker. “Red Demon” was a nickname for Bergoff, indicating that he frightened “reds” (communists), that is, strikebreakers.

- 5. perhaps the best known union anthem, sung to the tune of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”

- 6. Frey (1871–1957) was the head of the metal trades department in the American Federation of Labor.

- 7. The American Federation of Labor did not support the 1934 strikes.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.