Introduction

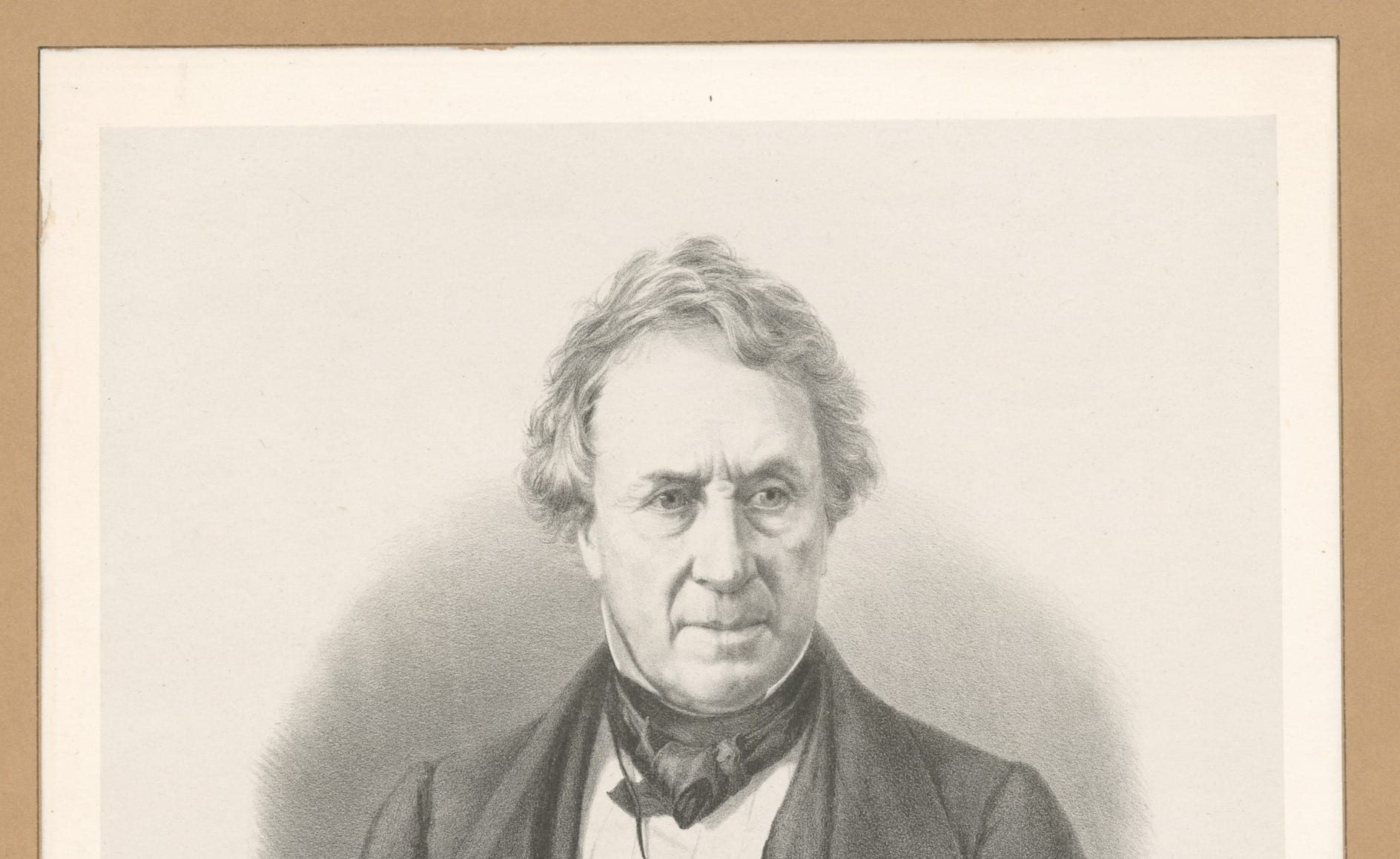

Thomas Ritchie was the editor of the Richmond Enquirer, which was one of the most influential newspapers in the South. Van Buren contacted Ritchie as part of Van Buren’s effort to build the first true party organization in America (see Autobiography). Part of Van Buren’s motivation was to prevent a repeat of the disastrous results of the 1824 election when multiple candidates necessitated a runoff election in the House of Representatives. Van Buren believed that a strong party organization would produce a clear winner in the Electoral College.

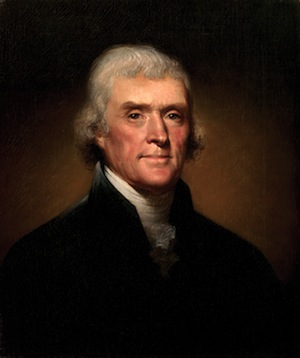

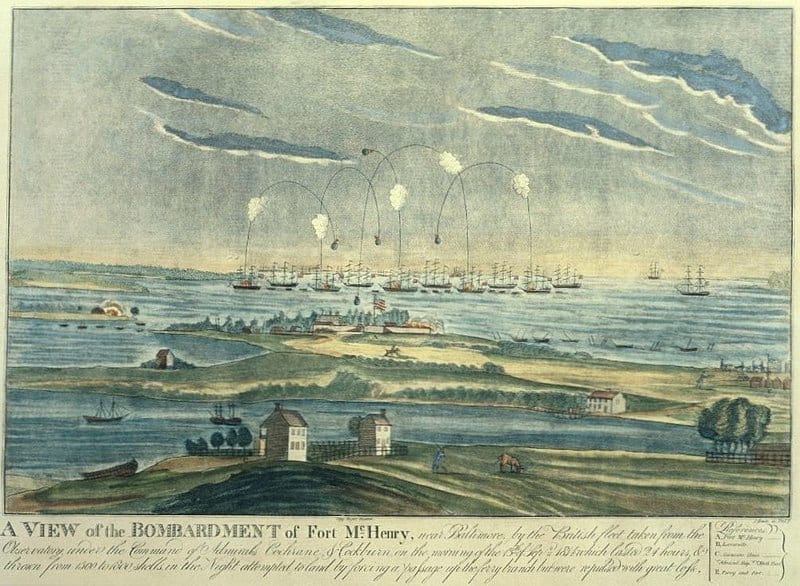

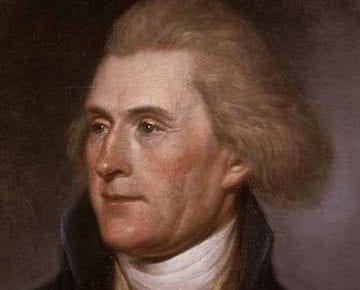

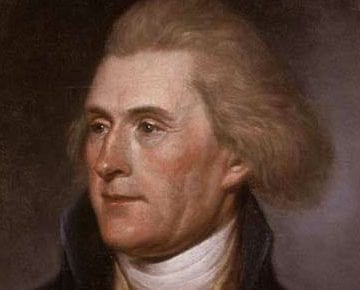

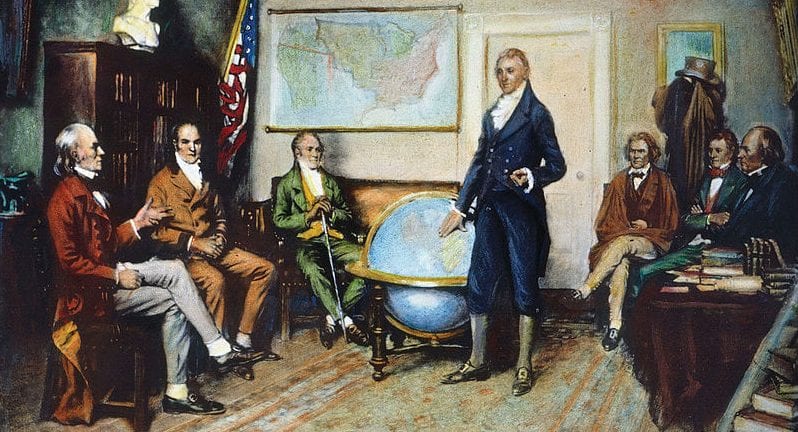

Building on the remnants of the old Democratic-Republican Party, Van Buren imagined a new party that would be more faithful to Jeffersonian principles. The Democratic-Republicans had become too nationalist in their orientation and threatened a return to Federalist principles. Van Buren tapped Andrew Jackson, a military hero from the War of 1812, to be the standard-bearer for the new Democratic Party, in hopes that his popularity would provide the necessary momentum the party needed to secure victory.

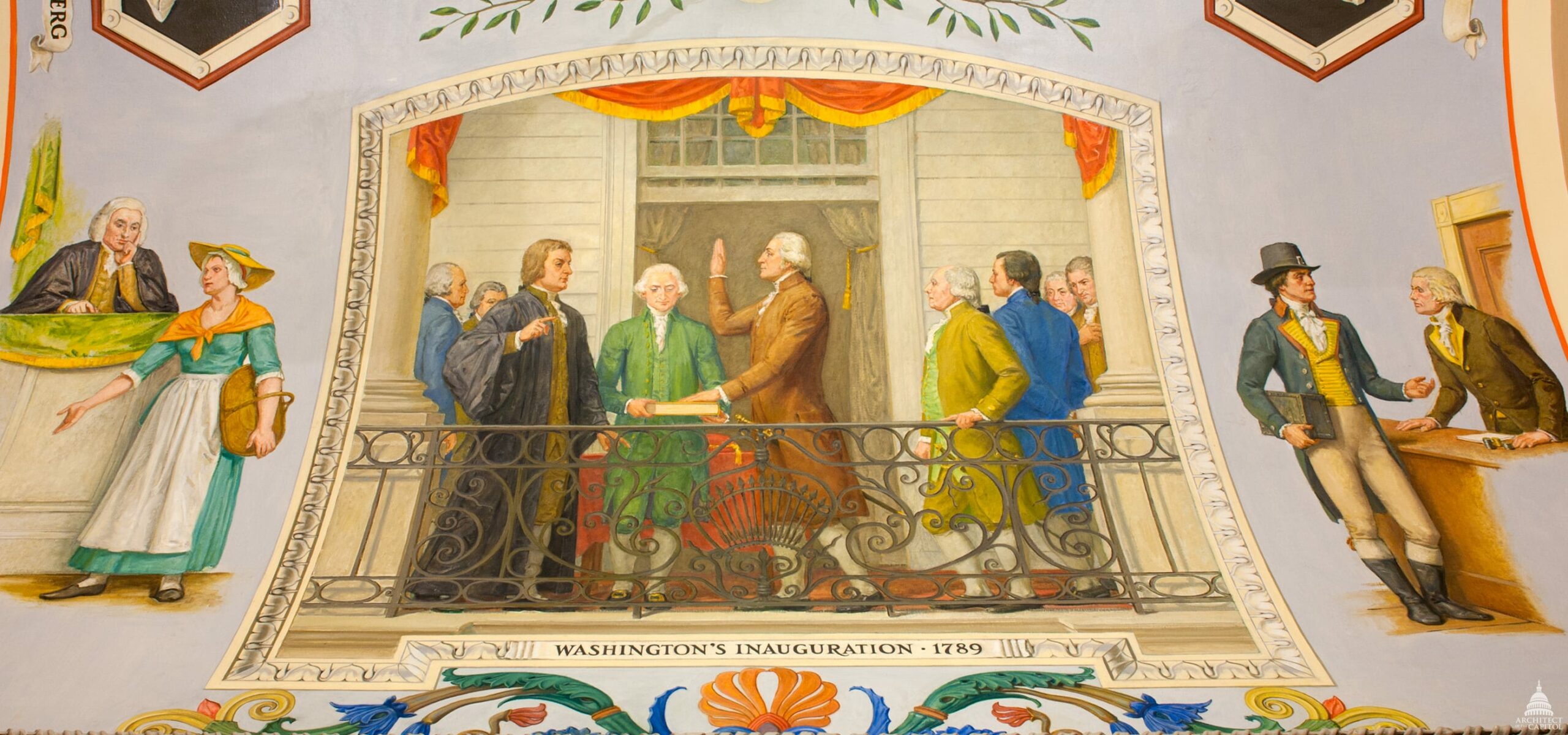

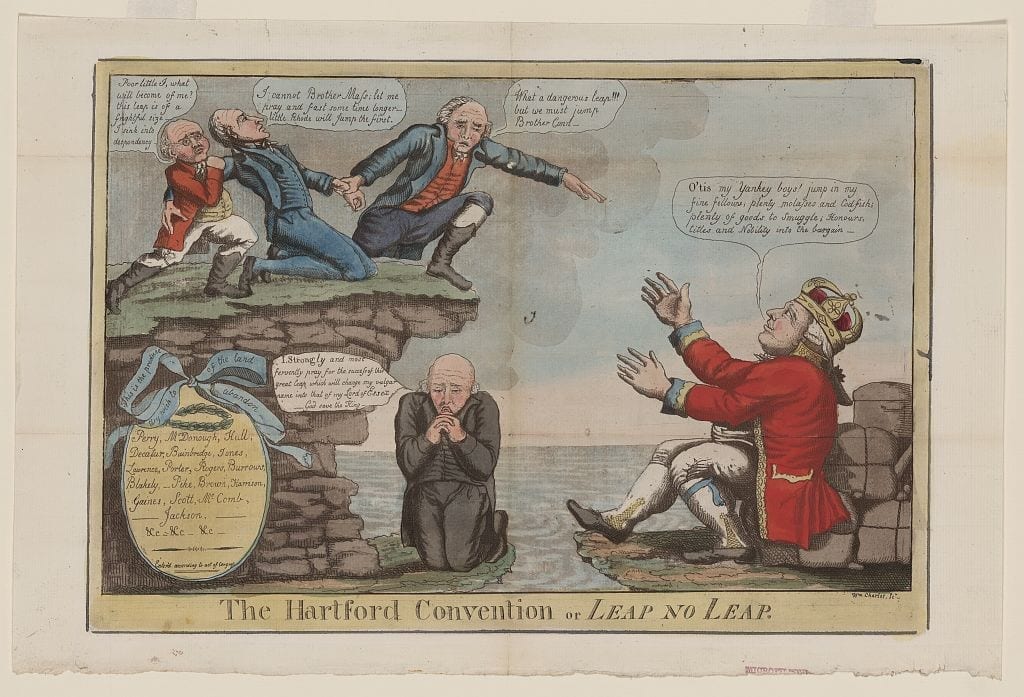

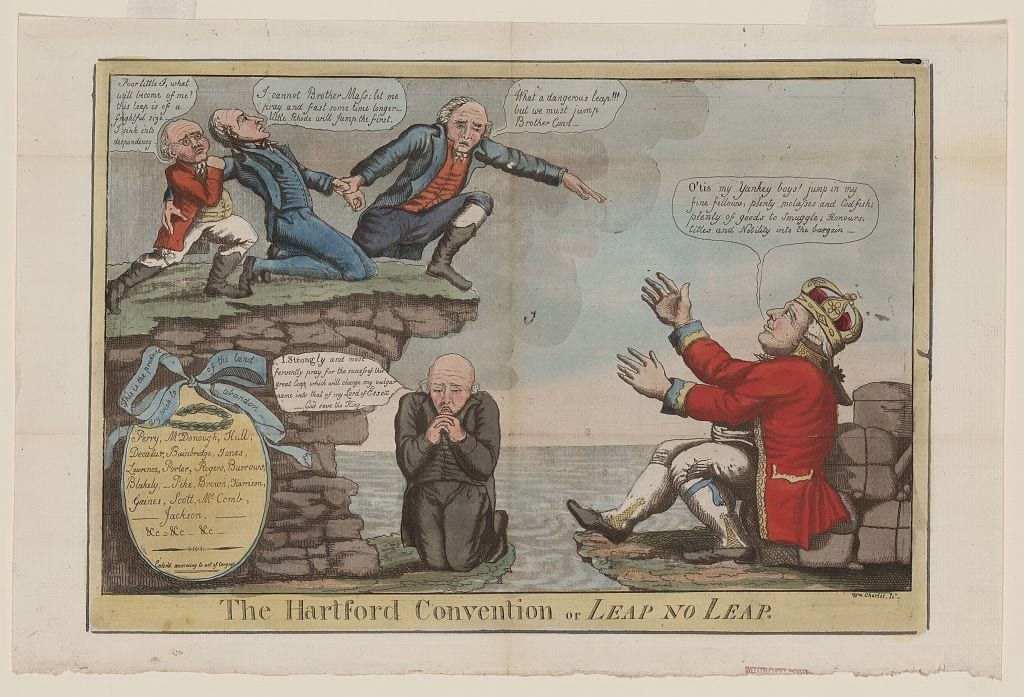

The Democrats engaged in grassroots campaigning and began the process of developing a national party organization. As part of that process, Van Buren and the Democrats introduced the party convention to replace the party caucus as a means of nominating presidential candidates. The conventions were far more democratic and participatory than the caucus that had derisively become known as “King Caucus.”

Van Buren’s efforts were rewarded when Jackson was elected president in 1828 and Van Buren was appointed secretary of state. Four years later, Van Buren was selected as Jackson’s running mate; in 1832, he was chosen to be Jackson’s successor to the presidency.

Source: “Martin Van Buren, Letter to Thomas Ritchie, January 13, 1827,” in History of U.S. Political Parties, vol. 1, ed. Arthur Schlesinger (New York: Chelsea House, 1973), 539–541.

Dear Sir,

You will have observed an article in the Argus upon the subject of a national convention. That matter will soon be brought under discussion here and I sincerely wish you would bestow upon it some portion of your attention….The following may, I think, justly be ranked among its probable advantages.

First, It is the best and probably the only practicable mode of concentrating the entire vote of the opposition and of effecting what is of still greater importance, the substantial re-organization of the Old Republican Party.

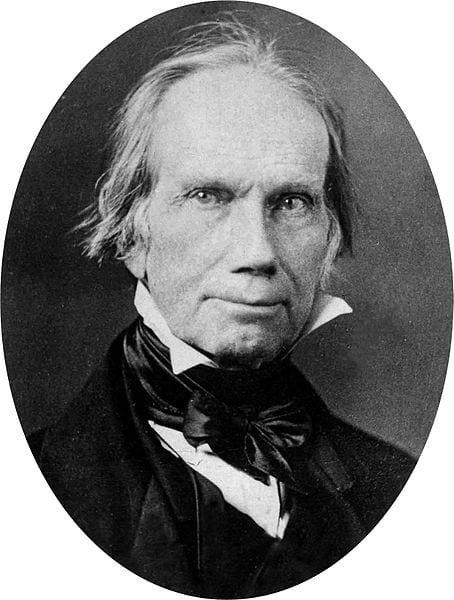

2nd Its first result cannot be doubtful. Mr. [John Quincy] Adams[1] occupying the seat and being determined not to surrender it except in extremis will not submit his pretensions to the convention. Noah’s[2] real or affected apprehensions upon that subject are idle. I have long been satisfied that we can only get rid of the present, and restore a better state of things, by combining General Jackson’s[3] personal popularity with the portion of old party feeling yet remaining. This sentiment is spreading, and would of itself be sufficient to nominate him at the Convention.

3rd. The call of such a convention, its exclusive Republican character, and the refusal of Mr. Adams[4] and his friends to become parties to it, would draw anew the old Party lines and the subsequent contest would re-establish them; state nomination alone would fall far short of that object.

4th It would greatly improve the condition of the Republicans of the North & Middle States by substituting party principle for personal preference as one of the leading points in the contest. The location of the candidates would in a great degree be merged in its consideration. Instead of the question being between a Northern and Southern man, it would be whether or not the ties, which have heretofore bound together a great political party should be severed. The difference between the two questions would be found to be immense in the elective field. Altho’ this is a mere party consideration it is not on that account less likely to be effectual. Considerations of this character not infrequently operate as efficiently as those which bear upon the most important questions of constitutional doctrine.

5thly It would place our Republican friends in New England on new and strong grounds. They would have to decide between an indulgence in sectional and personal feeling with an entire separation from their old political friends, on the one hand, or acquiescence in the fairly expressed will of the party, on the other. In all the states the divisions between Republicans and Federalists is still kept up and cannot be laid aside whatever the leaders of the two parties may desire. Such a question would greatly disturb the democracy of the east.

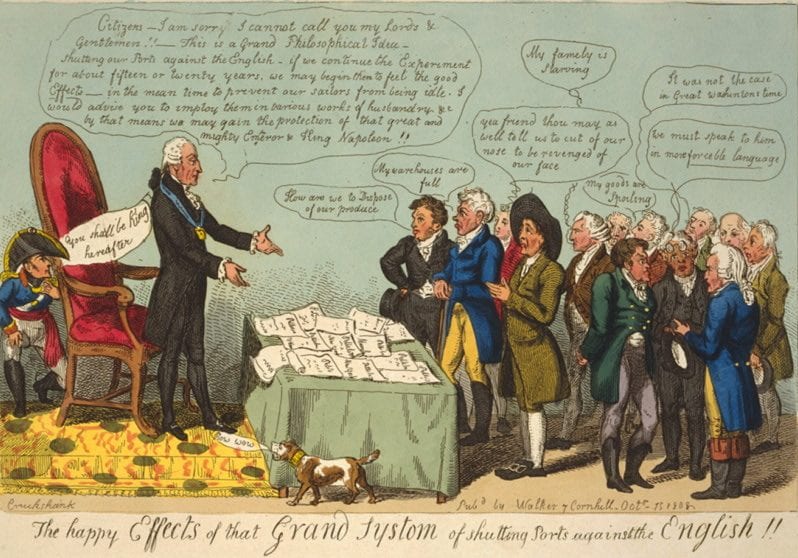

6th. Its effects would be highly salutary on your section of the union by the revival of old party distinctions. We must always have party distinctions and the old ones are the best of which the nature of the case admits. Political combinations between the inhabitants of the different states are unavoidable and the most natural and beneficial to the country is that between the planters of the South and the plain Republicans of the north. The country has once flourished under a party thus constituted and may again. It would take longer than our lives (even if it were practicable) to create new party feelings to keep those masses together. If the old ones are suppressed, geographical divisions founded on local interests or, what is worse prejudices between free and slaveholding states will inevitably take their place. Party attachment in former times furnished a complete antidote for sectional prejudices by producing counteracting feelings. It was not until that defense had been broken down that the clamor against Southern influence and African Slavery could be made effectual in the North. Those in the South who assisted in producing the change are, I am satisfied, now deeply sensible of their error. Formerly, attacks upon Southern Republicans were regarded by those of the north as assaults upon their political brethren and resented accordingly. This all powerful sympathy has been much weakened, if not, destroyed by the amalgamating policy of Mr. Monroe.[5] It can and ought to be revived and the proposed convention would be eminently serviceable in effecting that object.

Lastly, the effect of such a nomination on General Jackson could not fail to be considerable. His election, as the result of his military services without reference to party and so far as he alone is concerned scarcely to principle would be one thing. His election as the result of a combined and concerted effort of a political party, holding in the main, to certain tenets and opposed to certain prevailing principles, might be another and a far different thing.

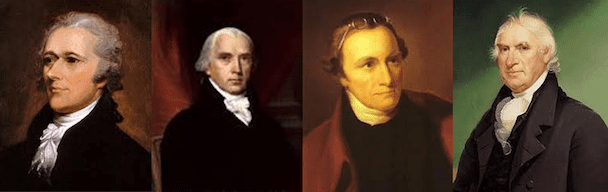

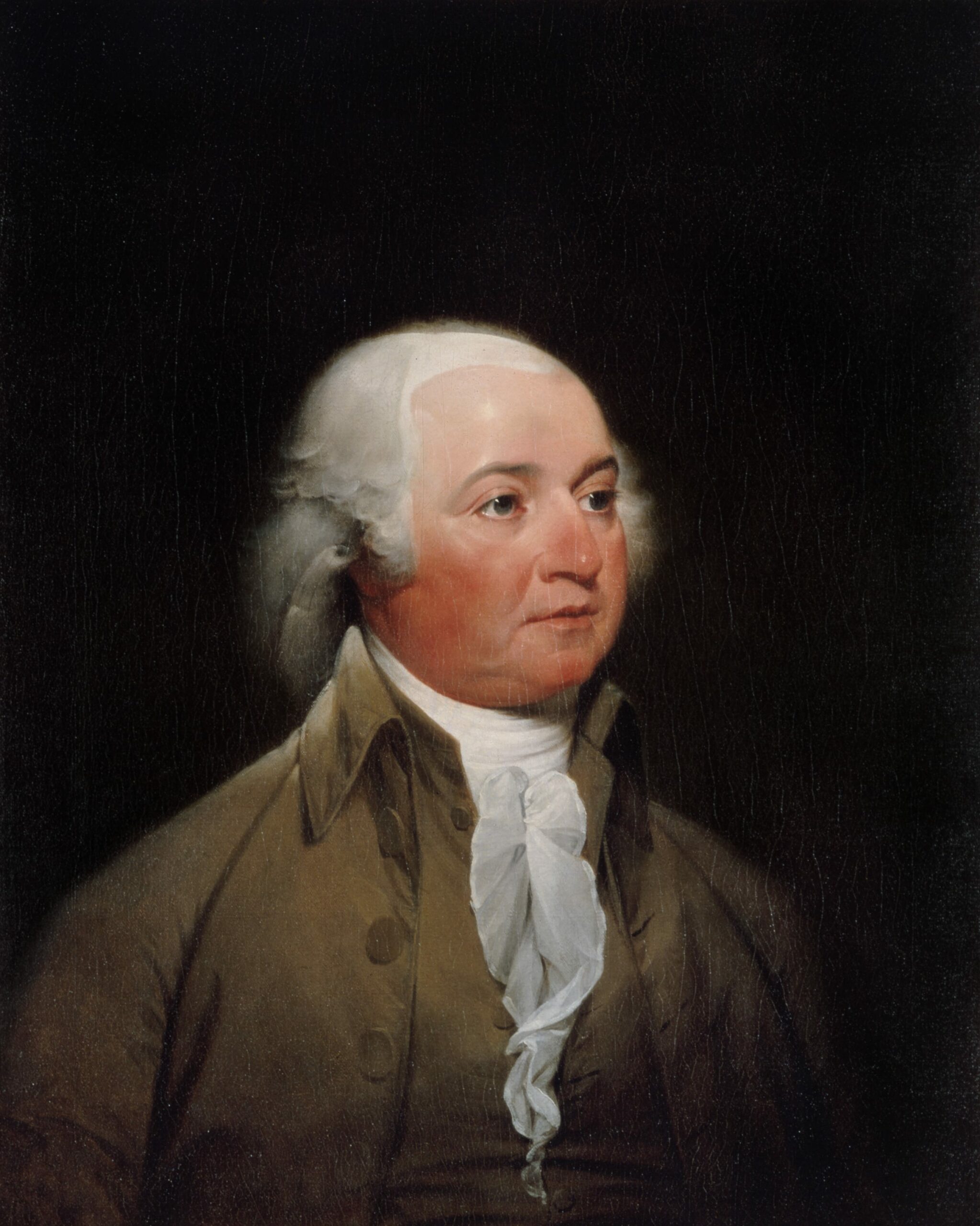

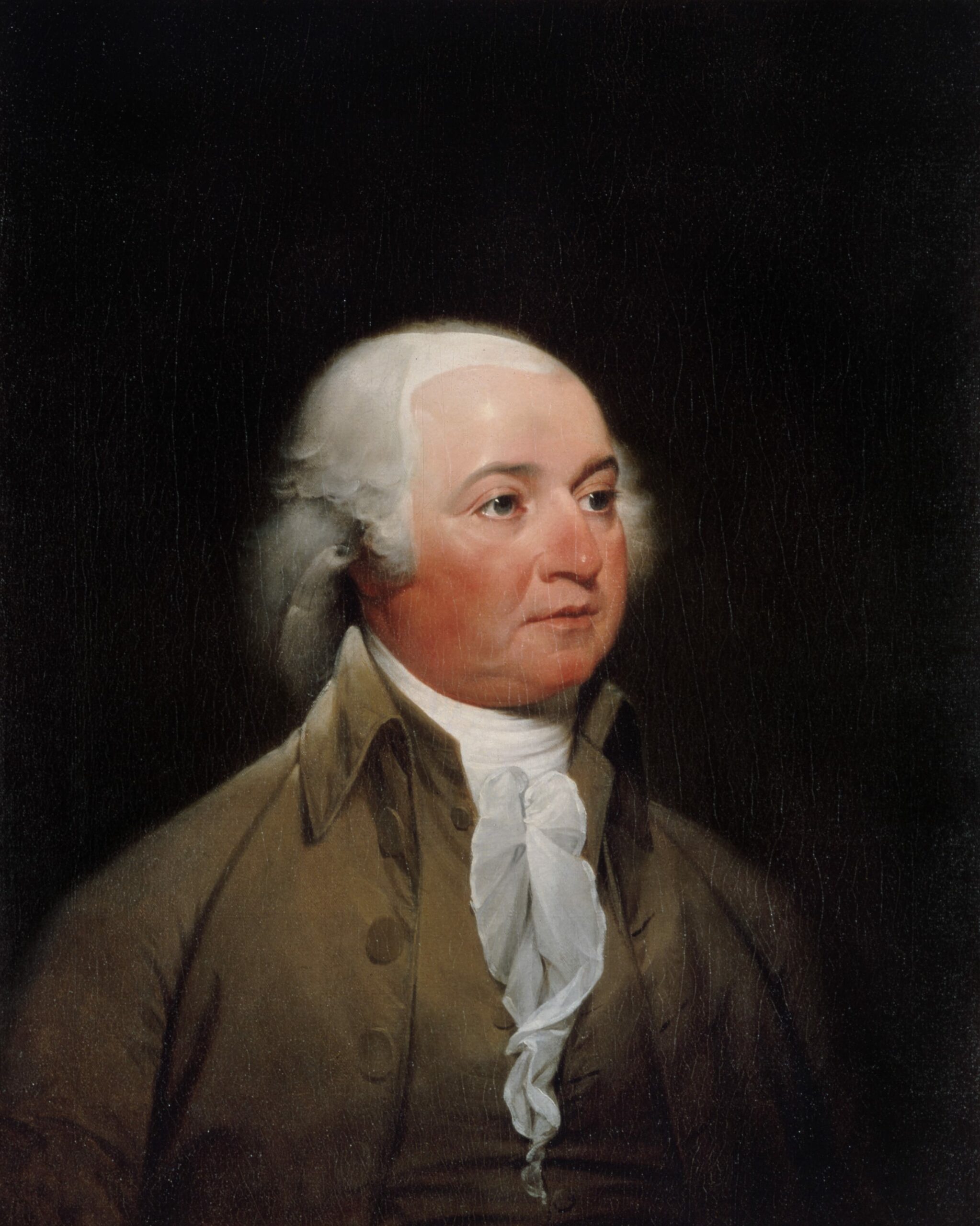

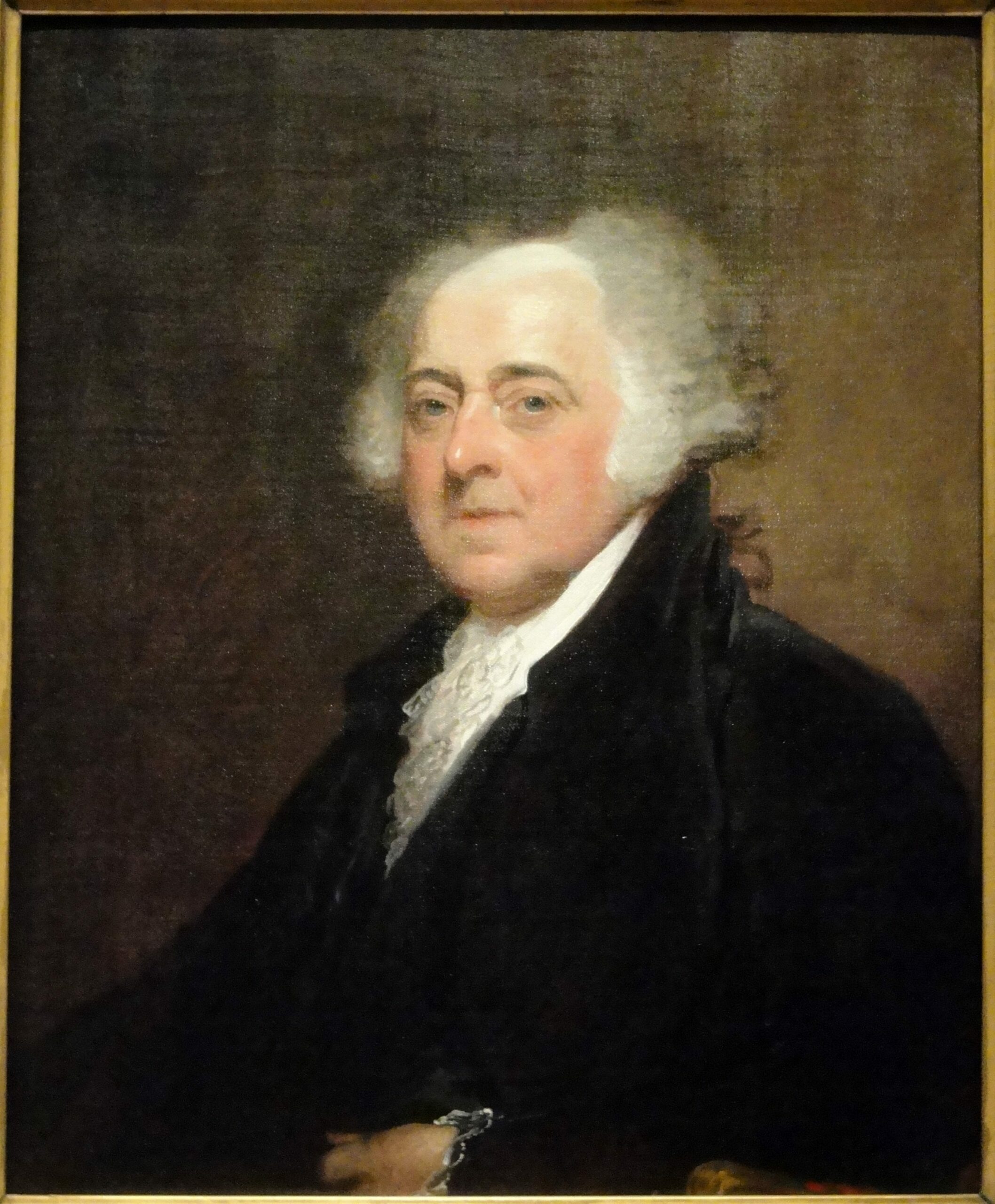

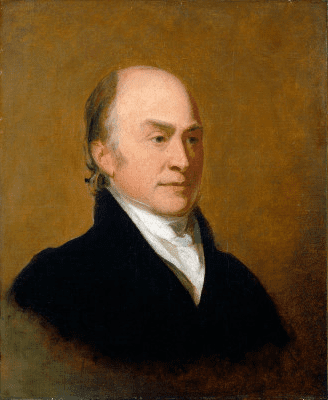

- 1. John Quincy Adams (1767–1848) began his political career as a diplomat, serving as minister to the Netherlands and then Prussia during his father’s administration. He later served in the US Senate, then as secretary of state under James Monroe. He then won the highly contentious election of 1824, after which he would serve only one term of office.

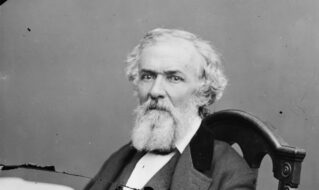

- 2. The “Noah” referenced here is likely Mordecai M. Noah, editor of the Courier and Enquirer, published in New York.

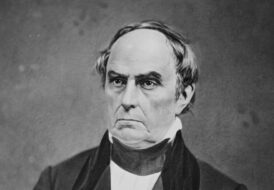

- 3. Andrew Jackson (1767–1845) earned national fame as a war hero and would later become president of the United States, leading the country as its most influential and polarizing figure.

- 4. John Quincy Adams (see FN 16).

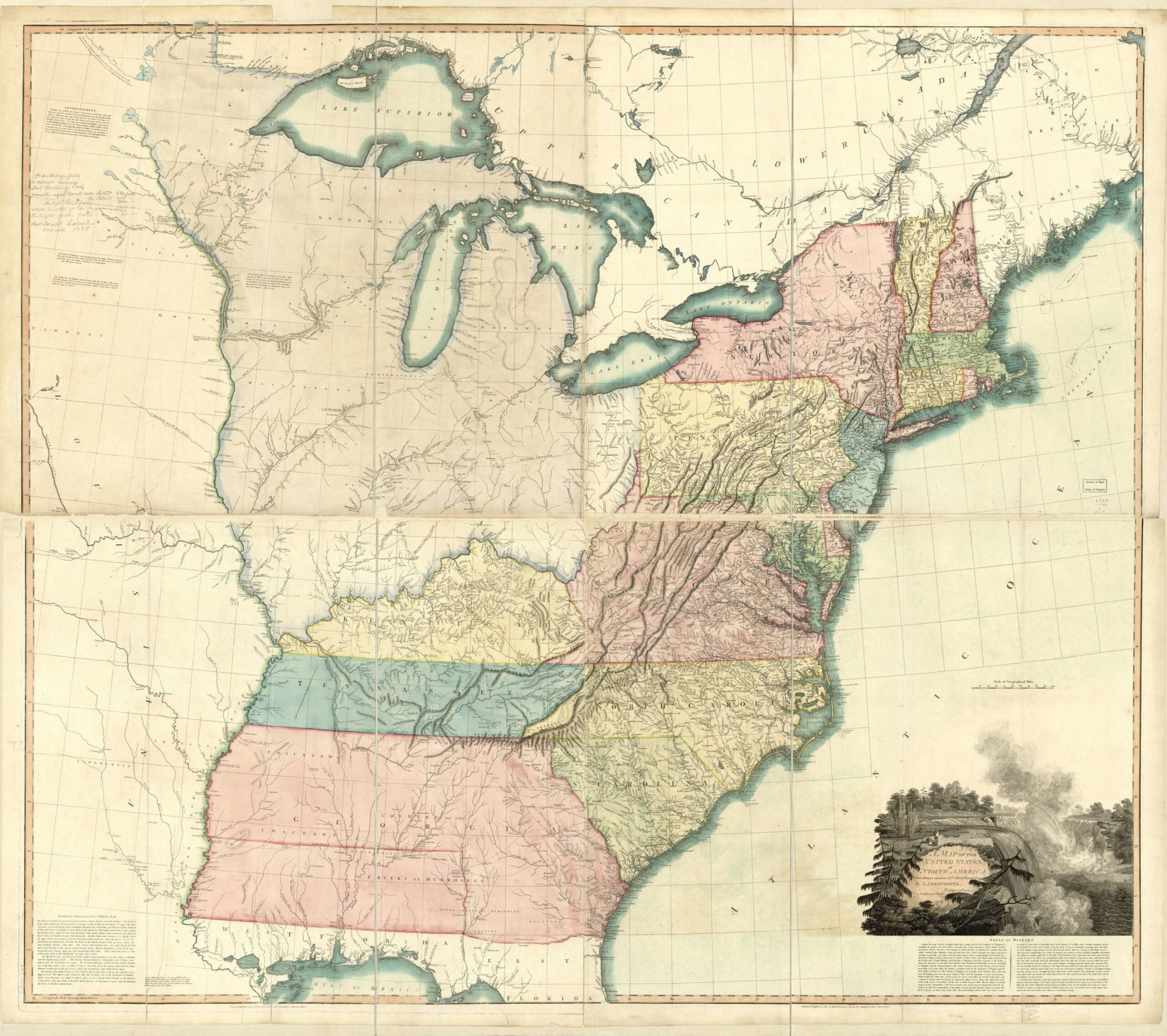

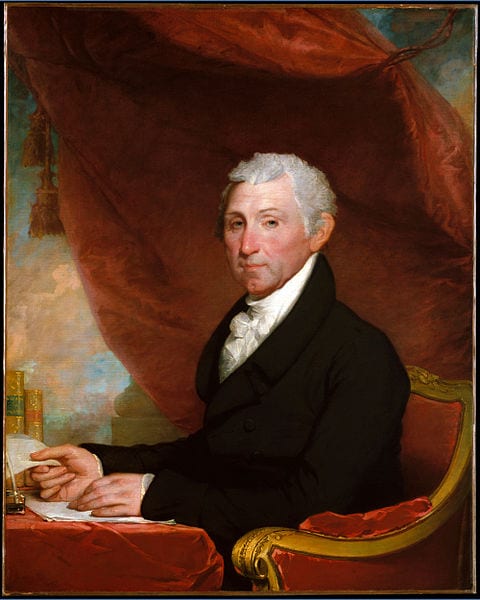

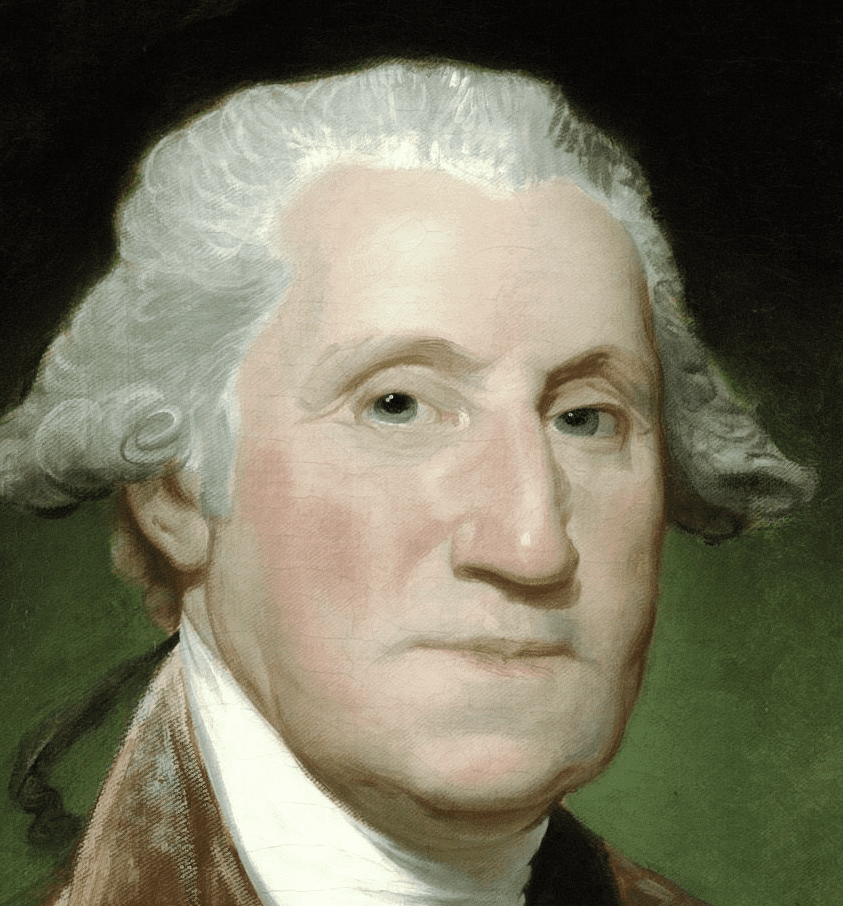

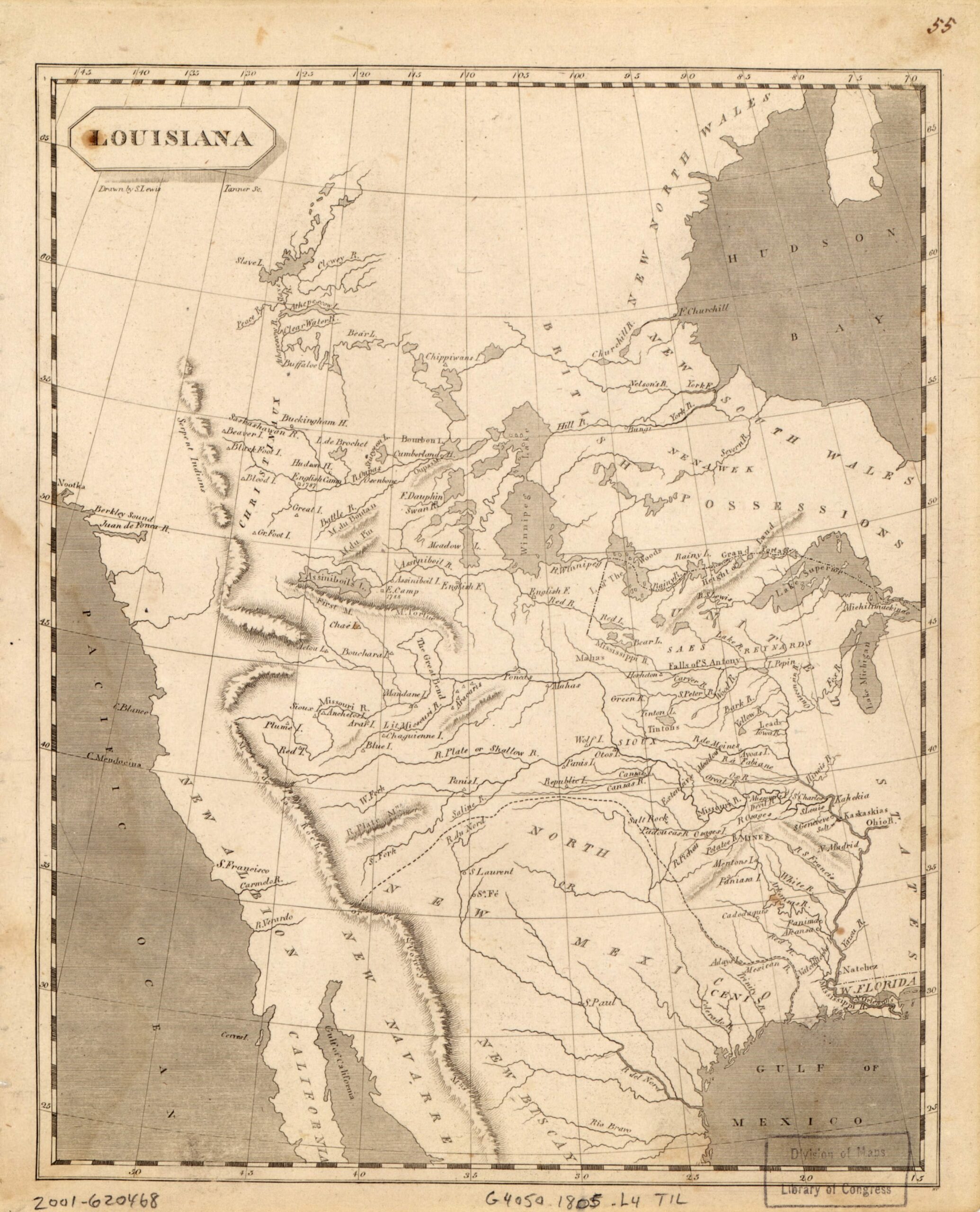

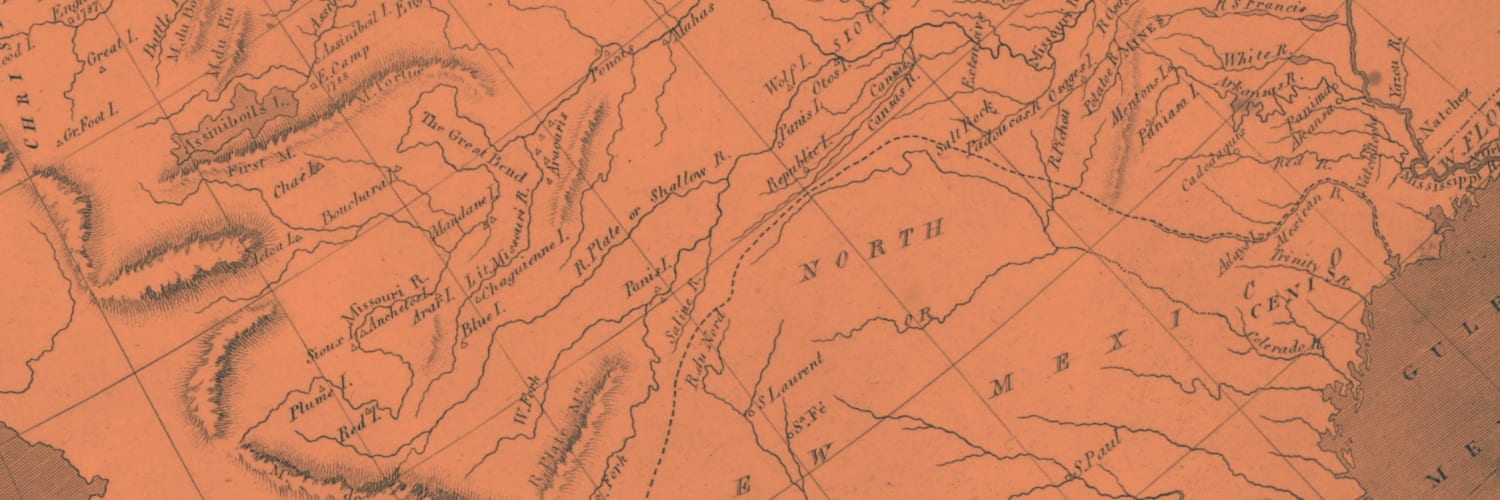

- 5. James Monroe (1758–1831 was the fifth United States president, known for overseeing westward expansion of the country and strengthening American foreign policy in 1823 with the Monroe Doctrine, which warned European powers about further colonization and intervention in the Western Hemisphere.

Annual Message to Congress (1827)

December 04, 1827

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.