Introduction

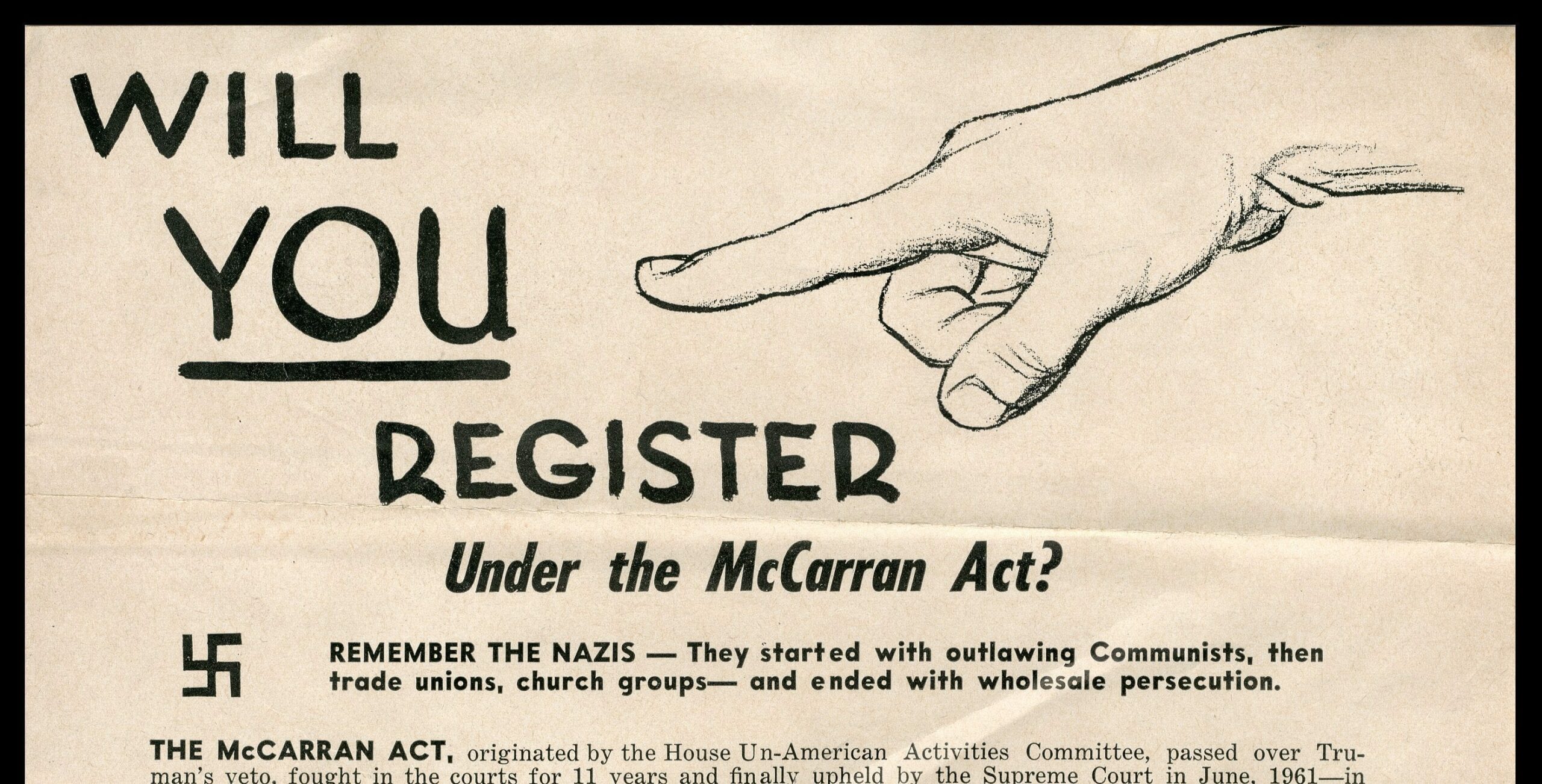

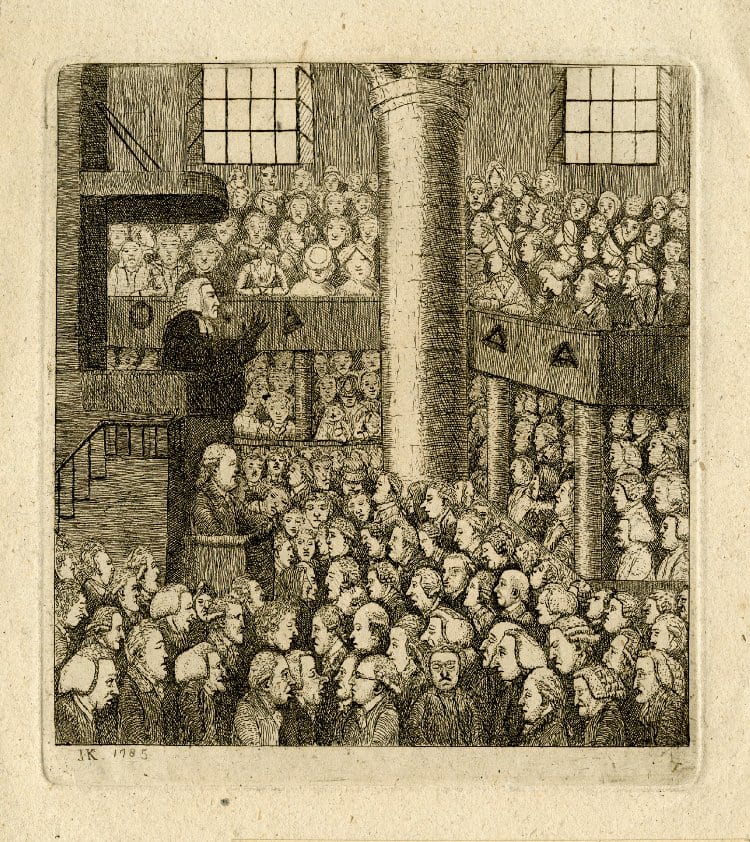

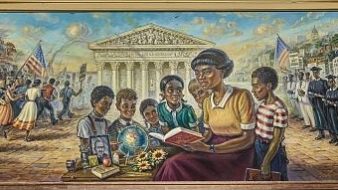

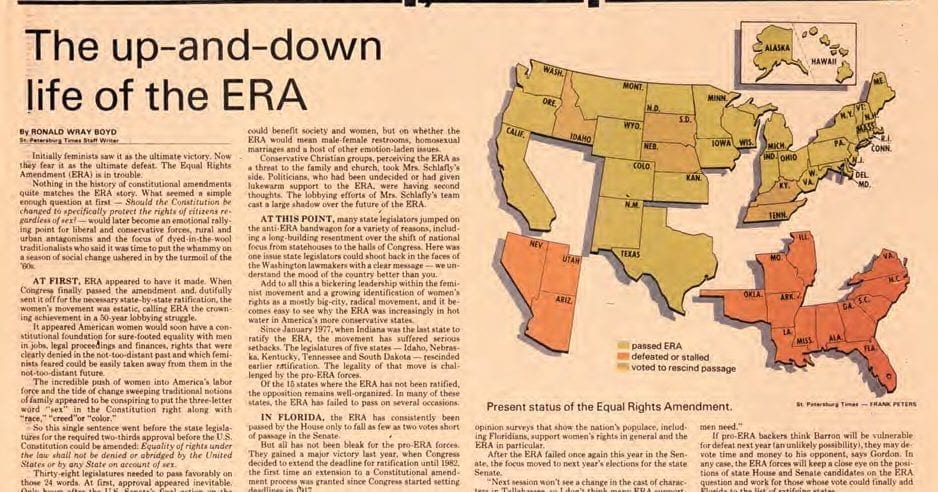

Like NAACP v. Alabama, New York Times v. Sullivan is at once a civil rights case and a landmark First Amendment case that determined the appropriate standard for the libel of public officials. The law of libel has its origins in English common law where aggrieved persons may recover civil damages for defamation—the public harming of one’s reputation through either libel (written words) or slander (spoken words). In Britain, the law of “seditious libel” allowed the government to bring suit against critics of the Crown or public ministers, even if the allegations were true. The law of seditious libel was ultimately rejected in American public law, but libel law remains to protect the reputation of individuals from false and malicious charges. Although narrowed by later opinions, Beauharnais v. Illinois provides an example of a “group libel” law that punishes the written defamation of certain groups on the basis of their race, creed, or color.

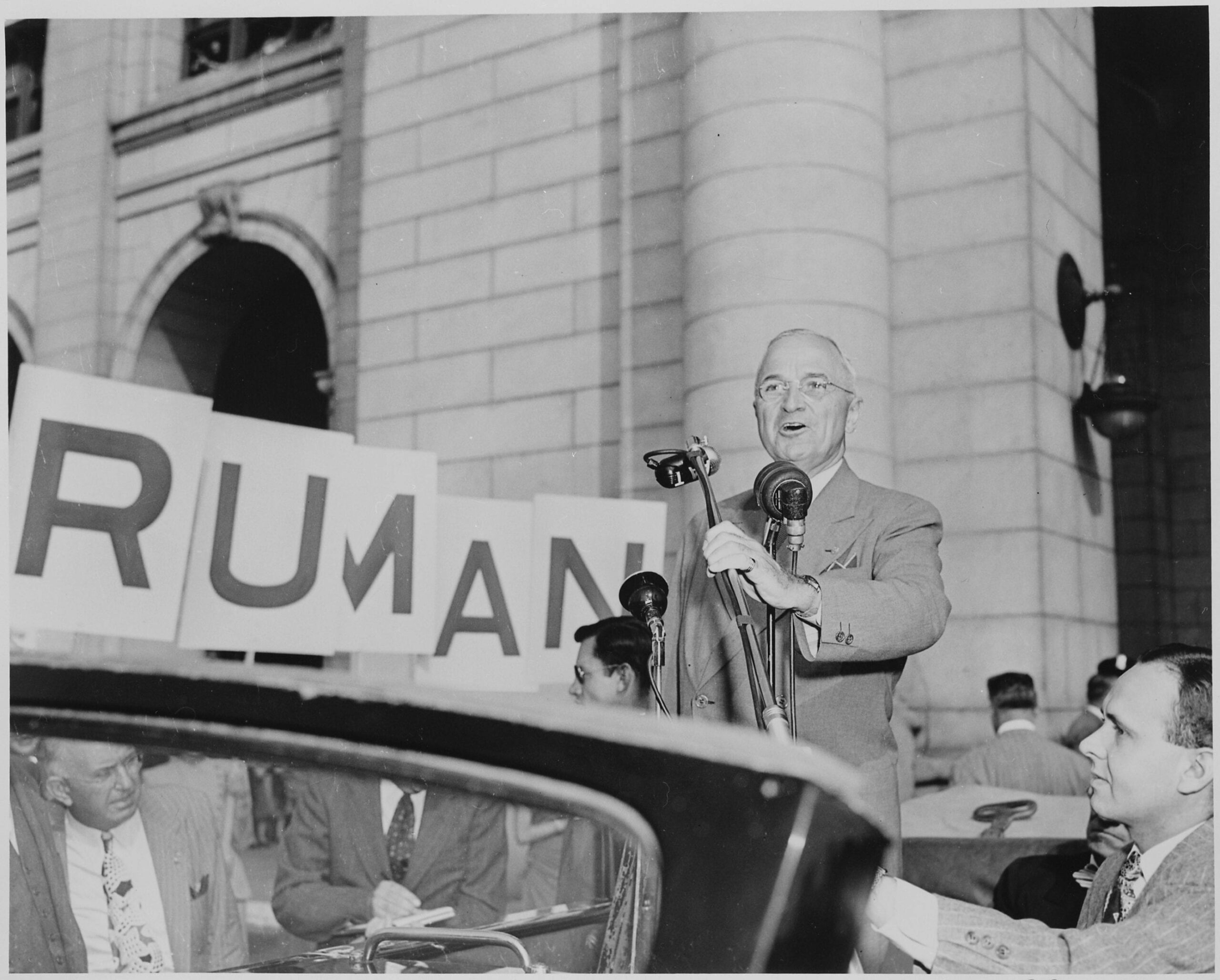

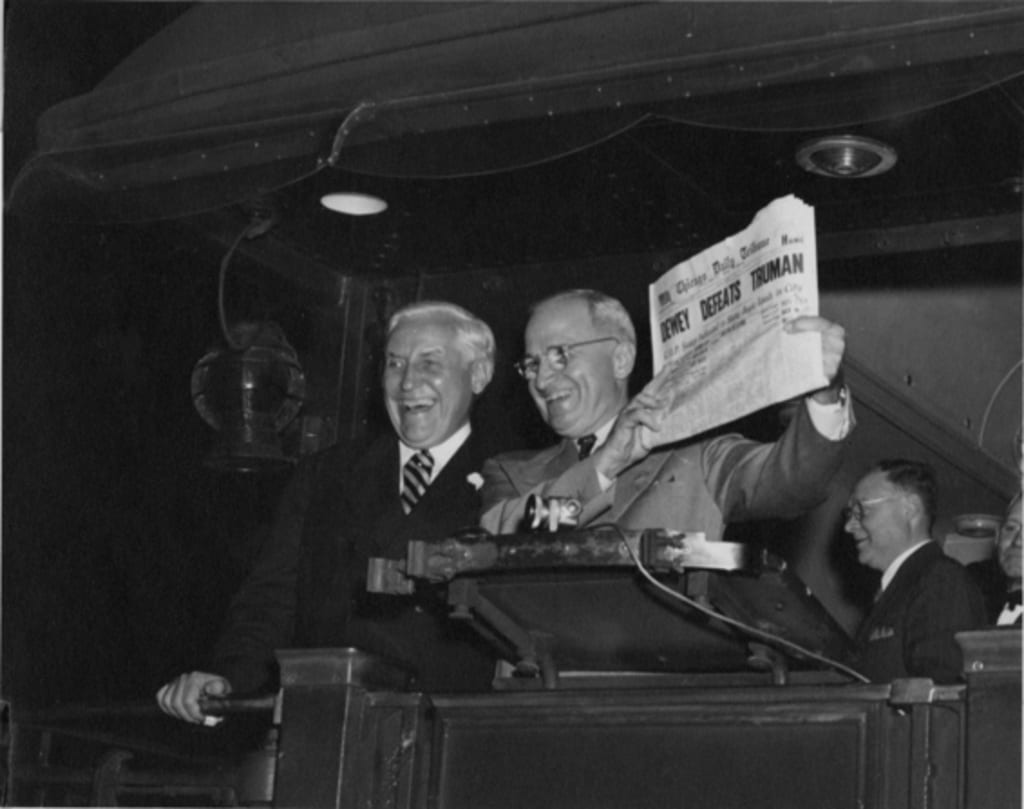

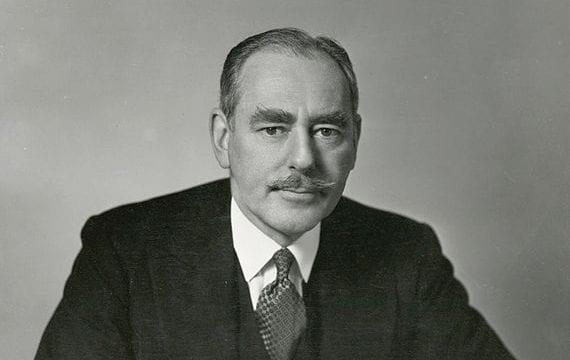

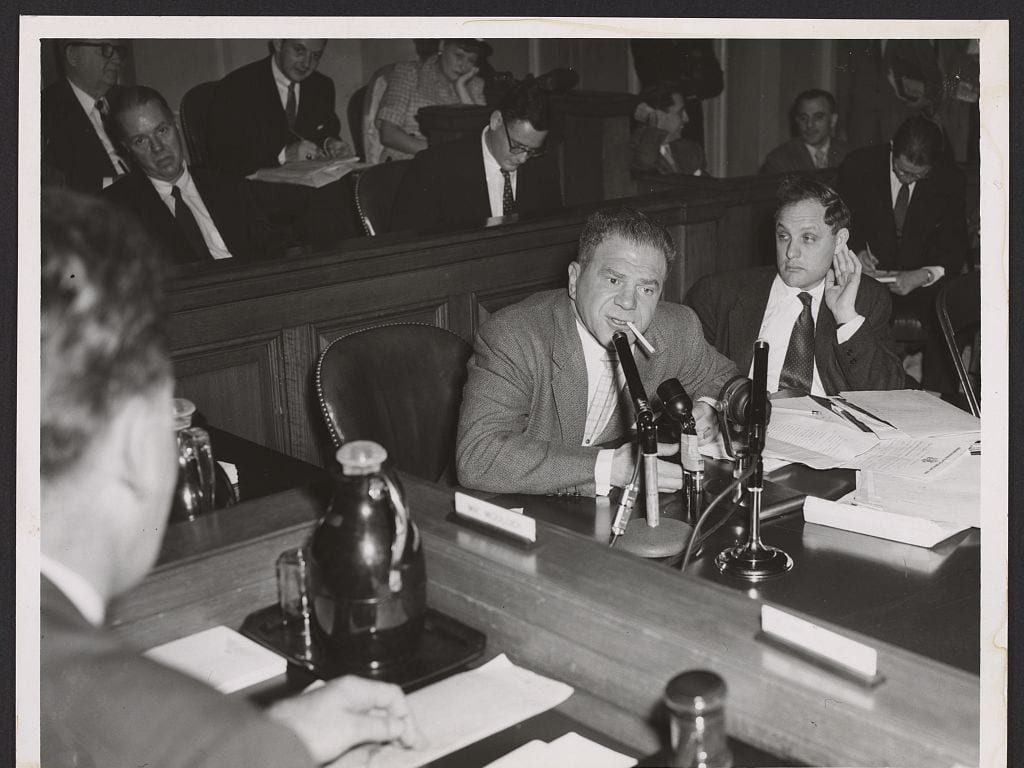

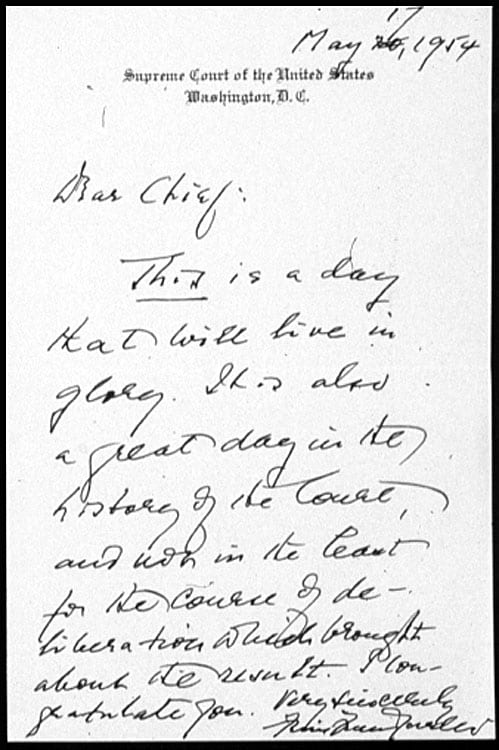

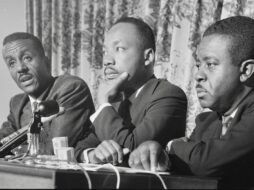

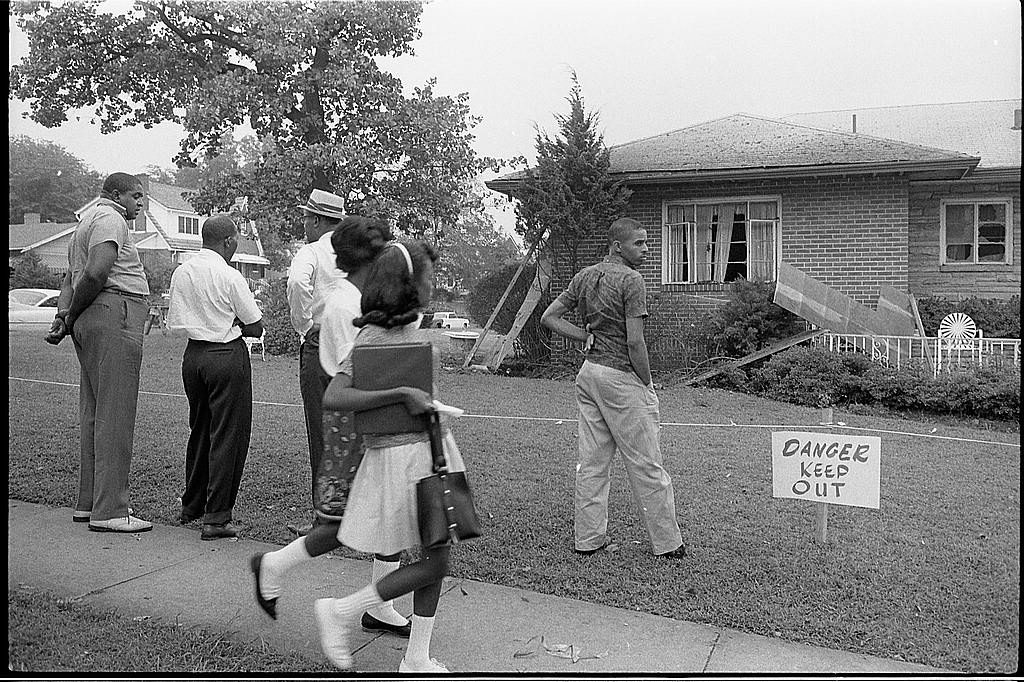

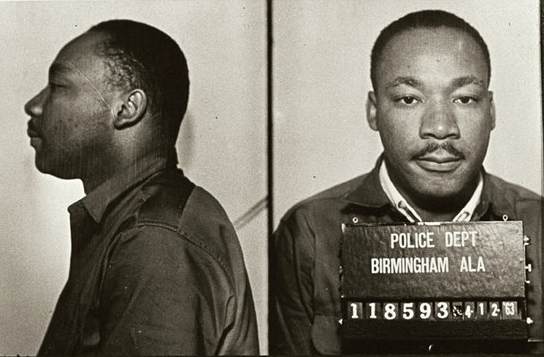

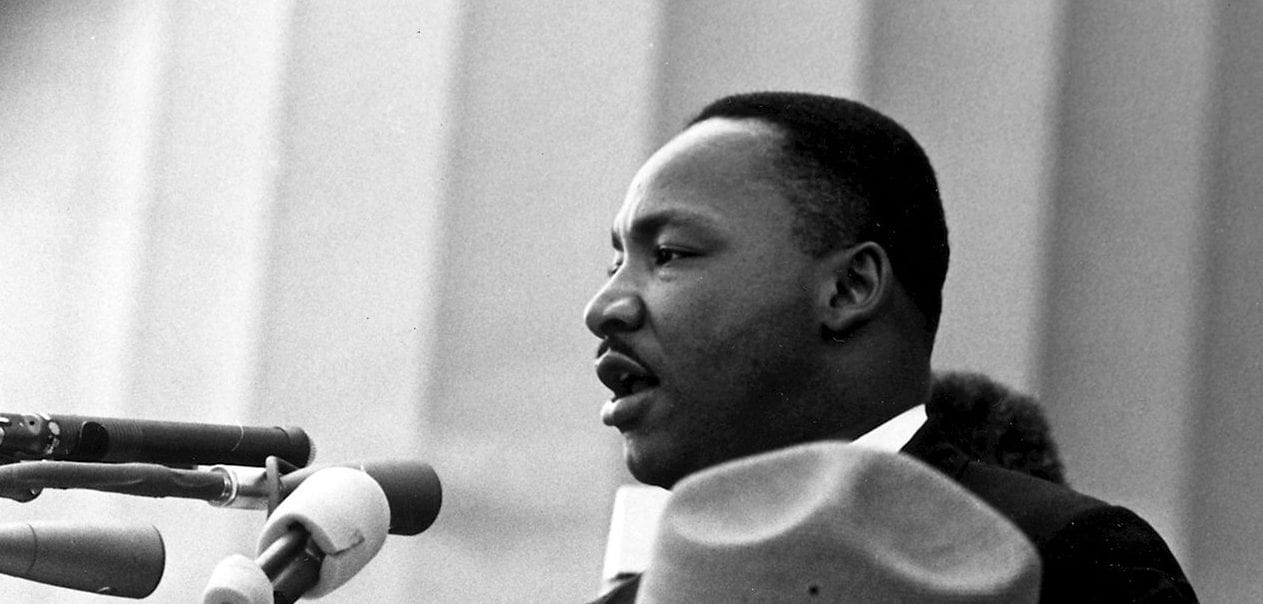

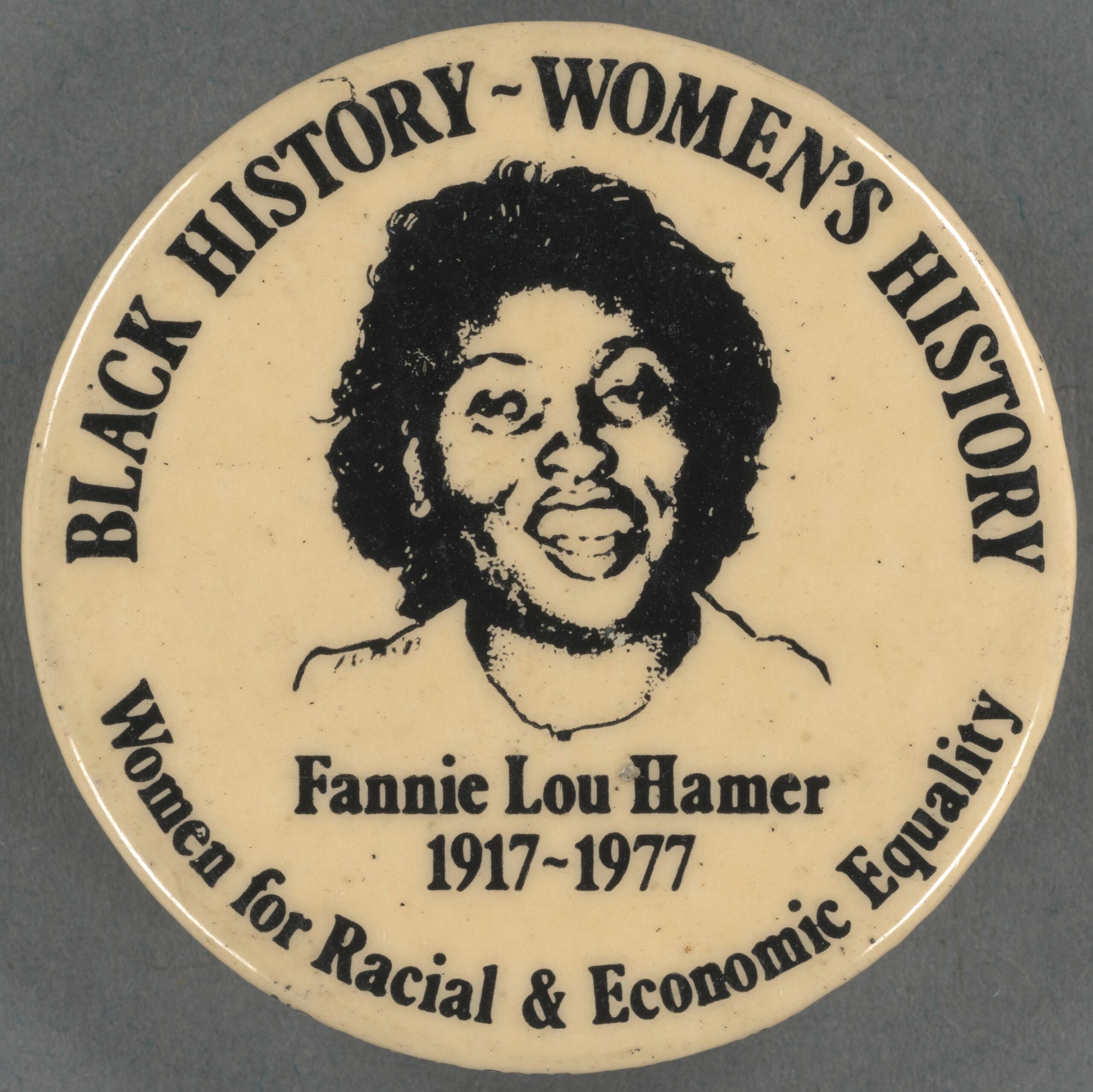

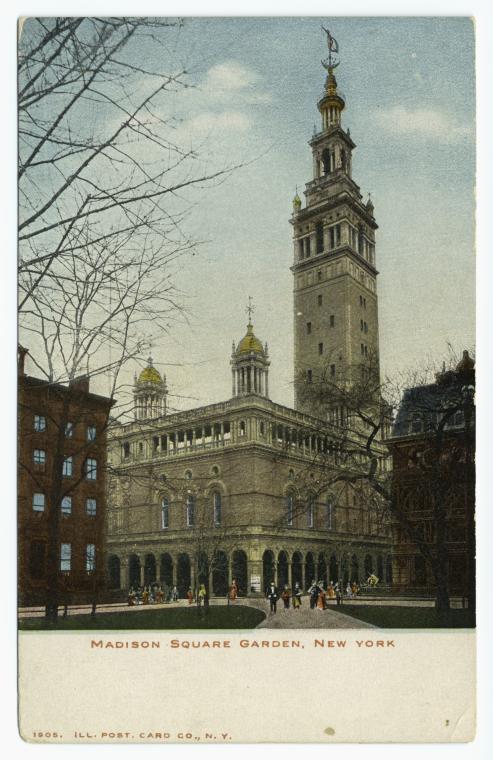

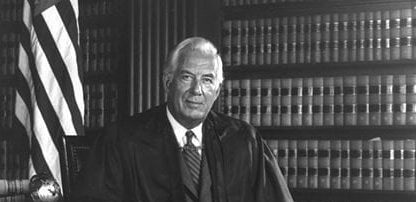

New York Times v. Sullivan came about at the height of the civil rights movement. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., placed an advertisement in the New York Times seeking support for its cause. The ad included some factual errors in its description of abuses by Alabama officials. For example, it mistook the number of times Dr. King was arrested and blamed public officials for the murder of a civil rights activist and for the chaining and padlocking of school doors to prevent students from joining in a protest. Although he was not named in the ad, Montgomery Public Safety Commissioner L. B. Sullivan sued for libel and won $500,000 in damages from an Alabama state court. In fact, Sullivan was not involved in the murder or in the padlocking of the school (which turned out to be a rumor). Justice Brennan reversed the Alabama court’s decision and adopted the now controlling “actual malice” test for libel: “The constitutional guarantees require, we think, a federal rule that prohibits a public official from recovering damages for a defamatory falsehood relating to his official conduct unless he proves that the statement was made with ‘actual malice’—that is, with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.”

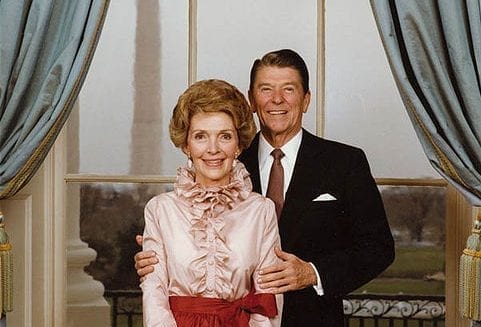

Times v. Sullivan established an extremely heavy burden for “public officials” to recover libel damages from critics, even if their speech includes factual inaccuracies. The Court’s robust protection of political speech sought to ensure greater public accountability of elected officials by making it more difficult for them to use libel suits as a way to shield themselves from criticism. In Hustler v. Falwell (1988), the Court extended the “actual malice” test to “public figures”—individuals who do not hold an official office like Sullivan but who nonetheless maintain a high profile in the advocacy of political causes. Thus, while libel remains a proscribed, punishable category of speech outside the protection of the First Amendment, the Court’s exacting definition of “actual malice” and “reckless disregard” of truth make it very difficult for “public officials” and “public figures” to recover civil damages in lawsuits against their critics.

Source: 376 U.S. 254, https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/376/254.

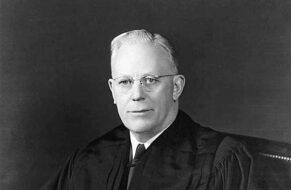

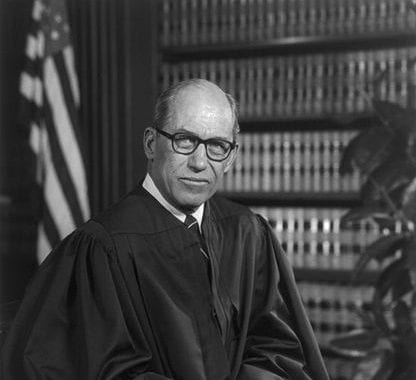

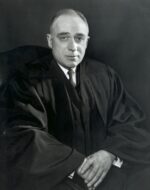

- JUSTICE BRENNAN delivered the opinion of the Court.

We are required in this case to determine for the first time the extent to which the constitutional protections for speech and press limit a state’s power to award damages in a libel action brought by a public official against critics of his official conduct. . . .

. . . We hold that the rule of law applied by the Alabama courts is constitutionally deficient for failure to provide the safeguards for freedom of speech and of the press that are required by the First and Fourteenth Amendments in a libel action brought by a public official against critics of his official conduct. We further hold that, under the proper safeguards, the evidence presented in this case is constitutionally insufficient to support the judgment for respondent. . . .

Under Alabama law, as applied in this case, a publication is “libelous per se” if the words “tend to injure a person . . . in his reputation” or to “bring [him] into public contempt”; the trial court stated that the standard was met if the words are such as to “injure him in his public office, or impute misconduct to him in his office, or want of official integrity, or want of fidelity to a public trust.” The jury must find that the words were published “of and concerning” the plaintiff, but, where the plaintiff is a public official, his place in the governmental hierarchy is sufficient evidence to support a finding that his reputation has been affected by statements that reflect upon the agency of which he is in charge. Once “libel per se” has been established, the defendant has no defense as to stated facts unless he can persuade the jury that they were true in all their particulars. . . .

The state rule of law is not saved by its allowance of the defense of truth. . . .

A rule compelling the critic of official conduct to guarantee the truth of all his factual assertions—and to do so on pain of libel judgments virtually unlimited in amount—leads to a comparable “self-censorship.” Allowance of the defense of truth, with the burden of proving it on the defendant, does not mean that only false speech will be deterred. Even courts accepting this defense as an adequate safeguard have recognized the difficulties of adducing legal proofs that the alleged libel was true in all its factual particulars. Under such a rule, would-be critics of official conduct may be deterred from voicing their criticism, even though it is believed to be true and even though it is, in fact, true, because of doubt whether it can be proved in court or fear of the expense of having to do so. They tend to make only statements which “steer far wider of the unlawful zone” (Speiser v. Randall). The rule thus dampens the vigor and limits the variety of public debate. It is inconsistent with the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

The constitutional guarantees require, we think, a federal rule that prohibits a public official from recovering damages for a defamatory falsehood relating to his official conduct unless he proves that the statement was made with “actual malice”—that is, with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not. . . .

We hold today that the Constitution delimits a state’s power to award damages for libel in actions brought by public officials against critics of their official conduct. Since this is such an action, the rule requiring proof of actual malice is applicable. . . .

Applying these standards, we consider that the proof presented to show actual malice lacks the convincing clarity which the constitutional standard demands, and hence that it would not constitutionally sustain the judgment for respondent under the proper rule of law. The case of the individual petitioners requires little discussion. Even assuming that they could constitutionally be found to have authorized the use of their names on the advertisement, there was no evidence whatever that they were aware of any erroneous statements or were in any way reckless in that regard. The judgment against them is thus without constitutional support.

As to the Times, we similarly conclude that the facts do not support a finding of actual malice. The statement by the Times’ secretary that, apart from the padlocking allegation, he thought the advertisement was “substantially correct,” affords no constitutional warrant for the Alabama Supreme Court’s conclusion that it was a “cavalier ignoring of the falsity of the advertisement [from which] the jury could not have but been impressed with the bad faith of the Times, and its maliciousness inferable therefrom.” The statement does not indicate malice at the time of the publication; even if the advertisement was not “substantially correct”—although respondent’s own proofs tend to show that it was—that opinion was at least a reasonable one, and there was no evidence to impeach the witness’ good faith in holding it. . . .

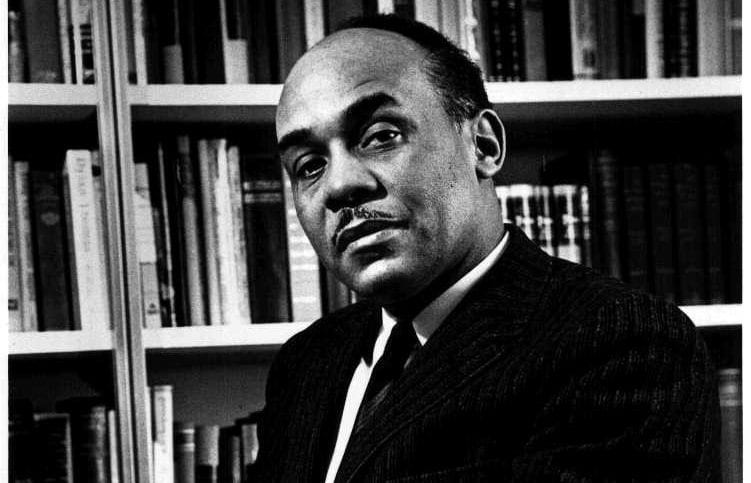

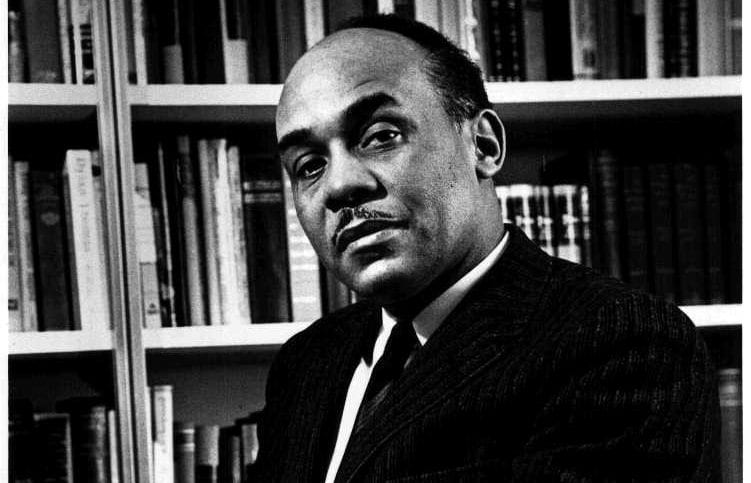

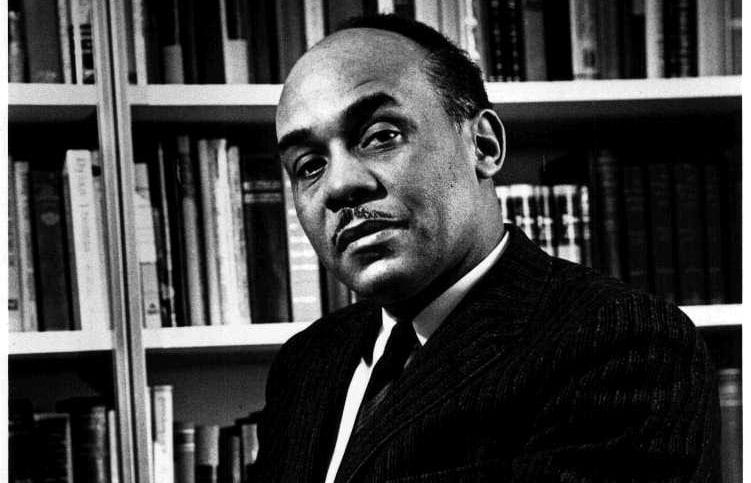

Finally, there is evidence that the Times published the advertisement without checking its accuracy against the news stories in the Times’ own files. The mere presence of the stories in the files does not, of course, establish that the Times “knew” the advertisement was false, since the state of mind required for actual malice would have to be brought home to the persons in the Times’ organization having responsibility for the publication of the advertisement. With respect to the failure of those persons to make the check, the record shows that they relied upon their knowledge of the good reputation of many of those whose names were listed as sponsors of the advertisement, and upon the letter from A. Philip Randolph, known to them as a responsible individual, certifying that the use of the names was authorized. There was testimony that the persons handling the advertisement saw nothing in it that would render it unacceptable under the Times’ policy of rejecting advertisements containing “attacks of a personal character”; their failure to reject it on this ground was not unreasonable. We think the evidence against the Times supports, at most, a finding of negligence in failing to discover the misstatements, and is constitutionally insufficient to show the recklessness that is required for a finding of actual malice. . . .

. . . Raising as it does the possibility that a good faith critic of government will be penalized for his criticism, the proposition relied on by the Alabama courts strikes at the very center of the constitutionally protected area of free expression. We hold that such a proposition may not constitutionally be utilized to establish that an otherwise impersonal attack on governmental operations was a libel of an official responsible for those operations. Since it was relied on exclusively here, and there was no other evidence to connect the statements with respondent, the evidence was constitutionally insufficient to support a finding that the statements referred to respondent.

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama is reversed, and the case is remanded to that court for further proceedings not inconsistent with this opinion.

Reversed and remanded.

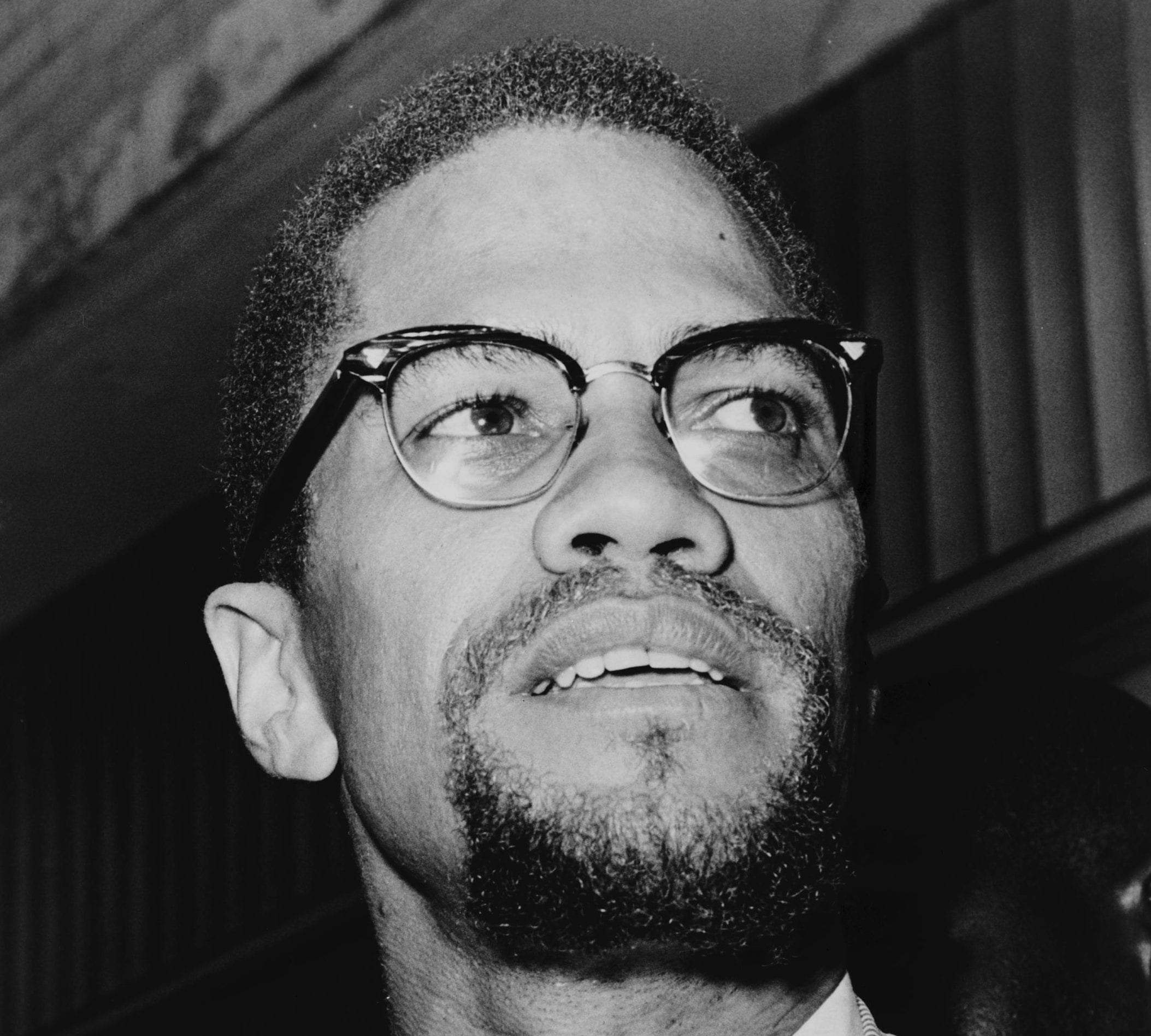

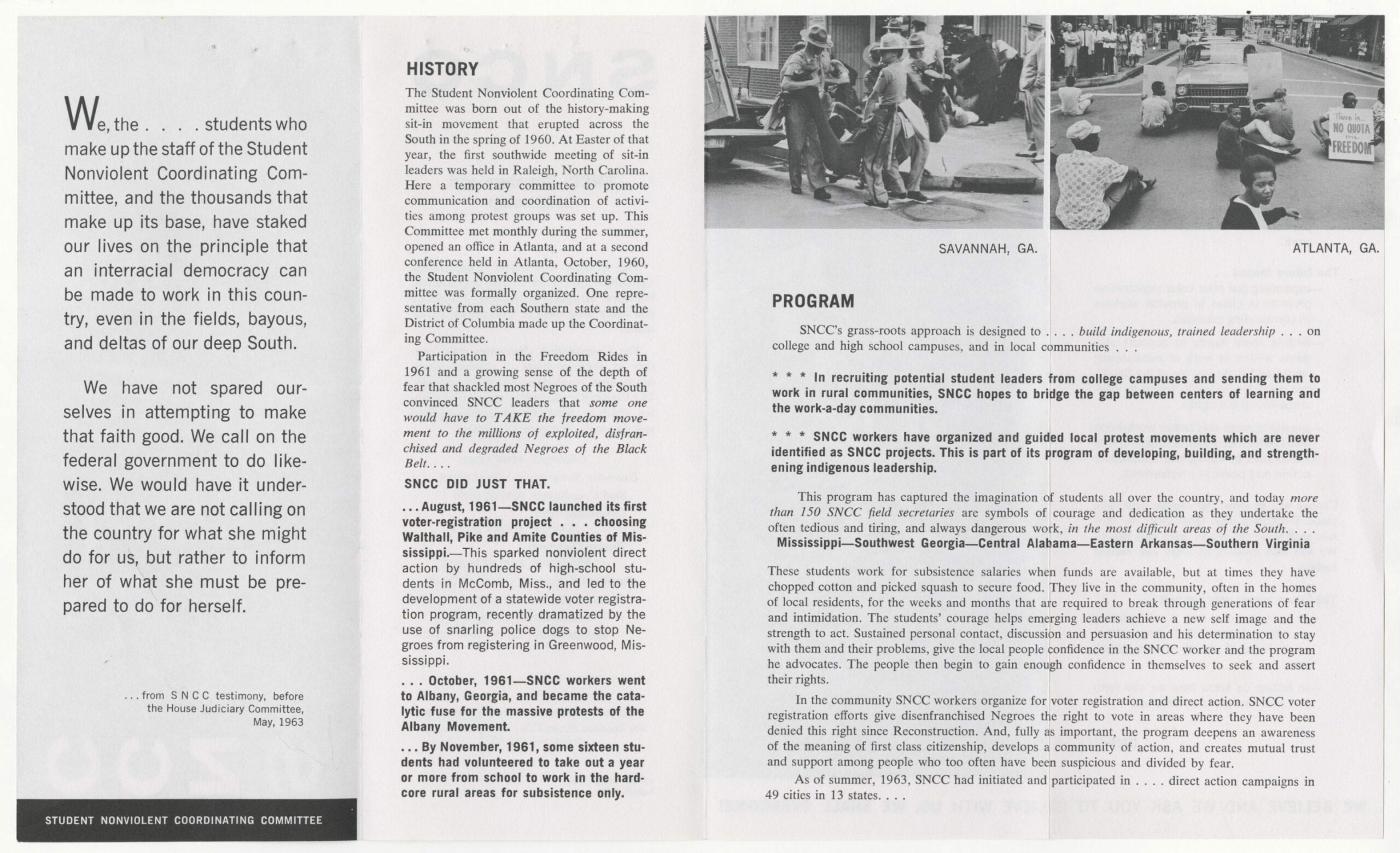

A Declaration of Independence

March 12, 1964

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.