No related resources

Introduction

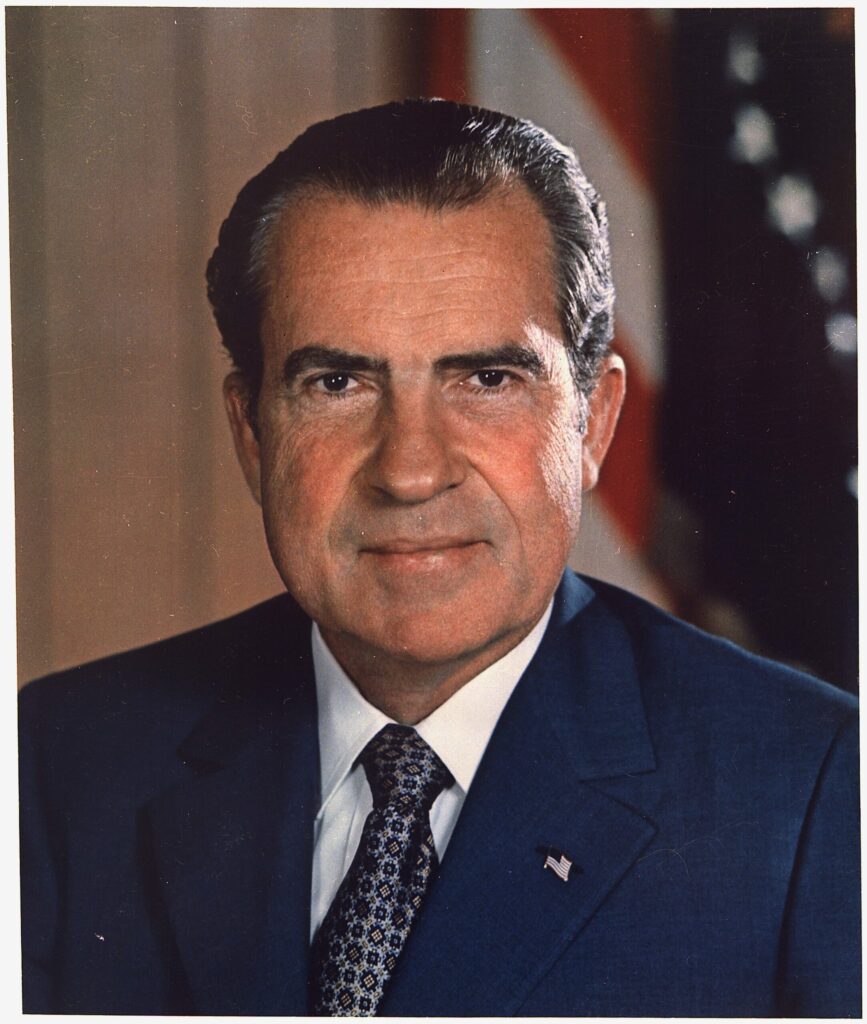

President Richard Nixon (1913–1994), who served from 1969 until his resignation in 1974, delivered a nationally televised public address on August 8, 1969, announcing his plan for a “New Federalism.” The policy was intended to change the way “responsibilities are shared between the state and the federal government” by limiting expansion of federal power and returning policy authority to the states. Nixon aimed to reconfigure welfare, job training, and poverty policies as well as the approach to federal grant programs more generally. Among Nixon’s proposals that were not adopted were his call for Congress to eliminate the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program and institute a new “family assistance system.” He had more success in persuading Congress to enact other components of his New Federalism program. For example, Congress eventually approved the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act of 1973 that achieved some of the goals Nixon sought in this policy area.

Nixon also called for adoption of revenue sharing—returning a portion of federal tax revenues to the states—which he viewed as “a gesture of faith in America’s state and local governments and in the principle of democratic self-government.” Congress approved a general revenue-sharing plan when it enacted the State and Local Assistance Act of 1972. Congress also took some other steps to achieving Nixon’s goals by adopting several special revenue-sharing programs, for instance by creating the Community Development Block Grant Program in 1974, which consolidated a number of existing grant programs and offered state and local governments more discretion in administering federal funds.

Source: Richard Nixon, Address to the Nation on Domestic Programs, Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/239998.

As you know, I returned last Sunday night from a trip around the world—a trip that took me to eight countries in nine days. The purpose of this trip was to help lay the basis for a lasting peace once the war in Vietnam is ended. In the course of it, I also saw once again the vigorous efforts so many new nations are making to leap the centuries into the modern world.

Every time I return to the United States after such a trip, I realize how fortunate we are to live in this rich land. We have the world’s most advanced industrial economy, the greatest wealth ever known to man, the fullest measure of freedom ever enjoyed by any people, anywhere.

Yet we, too, have an urgent need to modernize our institutions—and our need is no less than theirs.

We face an urban crisis, a social crisis—and at the same time, a crisis of confidence in the capacity of government to do its job.

A third of a century of centralizing power and responsibility in Washington has produced a bureaucratic monstrosity, cumbersome, unresponsive, ineffective.

A third of a century of social experiment has left us a legacy of entrenched programs that have outlived their time or outgrown their purposes.

A third of a century of unprecedented growth and change has strained our institutions and raised serious questions about whether they are still adequate to the times.

It is no accident, therefore, that we find increasing skepticism—and not only among our young people, but among citizens everywhere—about the continuing capacity of government to master the challenges we face.

Nowhere has the failure of government been more tragically apparent than in its efforts to help the poor, and especially in its system of public welfare....

My purpose tonight, however, is not to review the past record, but to present a new set of reforms—a new set of proposals—a new and drastically different approach to the way in which government cares for those in need, and to the way the responsibilities are shared between the state and the federal government.

I have chosen to do so in a direct report to the people because these proposals call for public decisions of the first importance; because they represent a fundamental change in the nation’s approach to one of its most pressing social problems; and because, quite deliberately, they also represent the first major reversal of the trend toward ever more centralization of government in Washington, DC. After a third of a century of power flowing from the people and the states to Washington it is time for a New Federalism in which power, funds, and responsibility will flow from Washington to the states and to the people....

This new approach is embodied in a package of four measures: First, a complete replacement of the present welfare system; second, a comprehensive new job training and placement program; third, a revamping of the Office of Economic Opportunity;1 and fourth, a start on the sharing of federal tax revenues with the states....

... I am also sending a message to Congress calling for a complete overhaul of the nation’s manpower training services.

The federal government’s job training programs have been a terrible tangle of confusion and waste.

To remedy the confusion, arbitrariness, and rigidity of the present system, the new Manpower Training Act would basically do three things.

—It would pull together the jumble of programs that presently exist, and equalize standards of eligibility.

—It would provide flexible funding so that federal money would follow the demands of labor and industry, and flow into those programs that people most want and most need.

—It would decentralize administration, gradually moving it away from the Washington bureaucracy and turning it over to states and localities.

In terms of its symbolic importance, I can hardly overemphasize this last point. For the first time, applying the principles of the New Federalism, administration of a major established federal program would be turned over to the states and local governments, recognizing that they are in a position to do the job better.

For years, thoughtful Americans have talked of the need to decentralize government. The time has come to begin.

Federal job-training programs have grown to vast proportions, costing more than a billion dollars a year. Yet they are essentially local in character. As long as the federal government continues to bear the cost, they can perfectly well be run by states and local governments, and that way they can be better adapted to specific state and local needs....

We come now to a proposal which I consider profoundly important to the future of our federal system of shared responsibilities. When we speak of poverty or jobs or opportunity or making government more effective or getting it closer to the people, it brings us directly to the financial plight of our states and cities.

We can no longer have effective government at any level unless we have it at all levels. There is too much to be done for the cities to do it alone, for Washington to do it alone, or for the states to do it alone.

For a third of a century, power and responsibility have flowed toward Washington, and Washington has taken for its own the best sources of revenue.

We intend to reverse this tide, and to turn back to the states a greater measure of responsibility—not as a way of avoiding problems, but as a better way of solving problems.

Along with this would go a share of federal revenues. I shall propose to the Congress next week that a set portion of the revenues from federal income taxes be remitted directly to the states, with a minimum of federal restrictions on how those dollars are to be used, and with a requirement that a percentage of them be channeled through for the use of local governments. The funds provided under this program will not be great in the first year. But the principle will have been established, and the amounts will increase as our budgetary situation improves.

This start on revenue sharing is a step toward what I call the New Federalism. It is a gesture of faith in America’s state and local governments and in the principle of democratic self-government...

- 1. The Office of Economic Opportunity was established in 1964 as part of the “war on poverty” launched by the Johnson administration. The office closed in 1981.

Address on the Vietnam War

November 03, 1969

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.