No related resources

Introduction

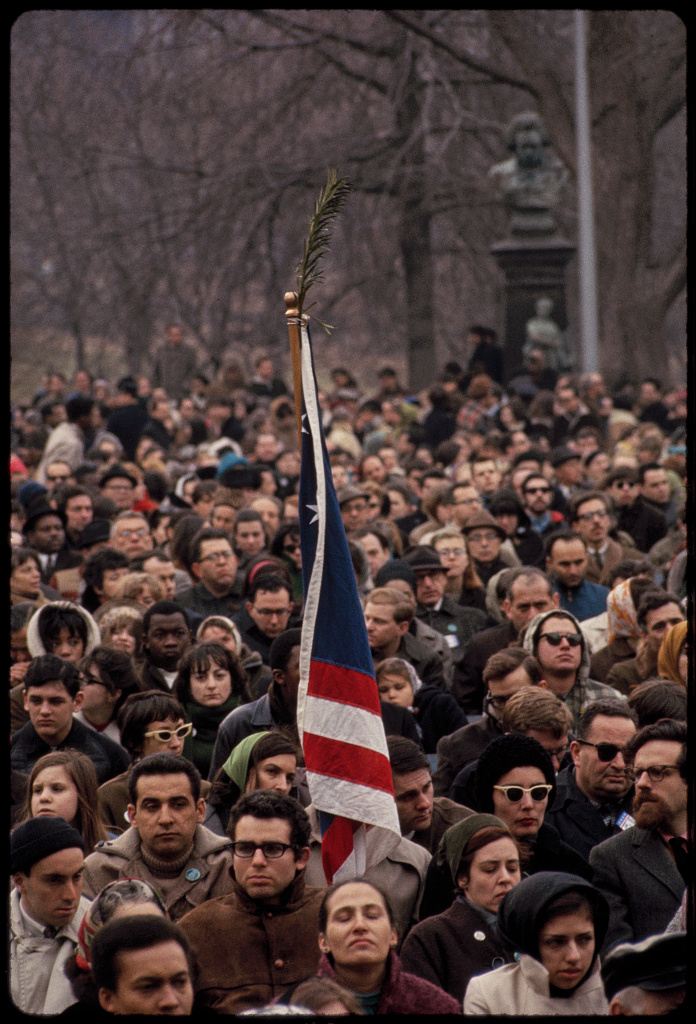

As a candidate for the presidency in 1968, Richard Nixon campaigned in part on a promise to end the war in Vietnam. This speech, delivered eleven months after his inauguration, provided the details of his plan to withdraw the United States from the conflict. Although the military situation had improved for U.S. and South Vietnamese forces, domestic support for the war continued to erode. Echoing his predecessor Lyndon Johnson, Nixon spoke of the need to demonstrate American determination to keep its promises; otherwise, instability and violence would spread globally. He also announced a new policy: Vietnamization or the Nixon Doctrine. According to this policy, the United States would assist in the defense of other nations, but those nations would have to supply the manpower for their defense. The Nixon Doctrine was thus a return to something like the Truman Doctrine. It showed a recognition that, contrary to the assumptions of earlier Cold War policies such as NSC 68, and the rhetoric of Kennedy’s Inaugural Address, the United States did not have unlimited resources to fight the Cold War. Acknowledging the effect of the anti-war demonstrations and seeking a counterweight, Nixon finished his speech by evoking “the great silent majority of” Americans who, he hoped, would support his efforts to end the war on terms acceptable to the United States. In a swipe at war opponents, the president also remarked, “North Vietnam cannot defeat or humiliate the United States. Only Americans can do that.”

Source: Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Richard Nixon, 1969 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1971), 901–9. Available online at Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum. https://goo.gl/WwSY6R.

Good evening, my fellow Americans:

Tonight I want to talk to you on a subject of deep concern to all Americans and to many people in all parts of the world – the war in Vietnam.

. . .

. . . I would like to answer some of the questions that I know are on the minds of many of you listening to me.

How and why did America get involved in Vietnam in the first place?

How has this administration changed the policy of the previous administration?

What has really happened in the negotiations in Paris1 and on the battlefront in Vietnam?

What choices do we have if we are to end the war?

What are the prospects for peace?

Now, let me begin by describing the situation I found when I was inaugurated on January 20.

– The war had been going on for 4 years.

– 31,000 Americans had been killed in action.

– The training program for the South Vietnamese was behind schedule.

– 540,000 Americans were in Vietnam with no plans to reduce the number.

– No progress had been made at the negotiations in Paris and the United States had not put forth a comprehensive peace proposal.

– The war was causing deep division at home and criticism from many of our friends as well as our enemies abroad.

In view of these circumstances there were some who urged that I end the war at once by ordering the immediate withdrawal of all American forces.

From a political standpoint this would have been a popular and easy course to follow. . . .

. . . [but] I had to think of the effect of my decision on the next generation and on the future of peace and freedom in America and in the world.

Let us all understand that the question before us is not whether some Americans are for peace and some are against peace. The question at issue is not whether Johnson’s war becomes Nixon’s war.

The great question is: How can we win America’s peace?

Well, let us turn now to the fundamental issue. Why and how did the United States become involved in Vietnam in the first place?

Fifteen years ago North Vietnam, with the logistical support of Communist China and the Soviet Union, launched a campaign to impose a Communist government on South Vietnam by instigating and supporting a revolution.

In response to the request of the Government of South Vietnam, President Eisenhower sent economic aid and military equipment to assist the people of South Vietnam in their efforts to prevent a Communist takeover. Seven years ago, President Kennedy sent 16,000 military personnel to Vietnam as combat advisers. Four years ago, President Johnson sent American combat forces to South Vietnam. . . .

. . . Now that we are in the war, what is the best way to end it?

In January I could only conclude that the precipitate withdrawal of American forces from Vietnam would be a disaster not only for South Vietnam but for the United States and the cause of peace.

For the South Vietnamese, our precipitate withdrawal would inevitably allow the Communists to repeat the massacres which followed their takeover in the North 15 years before . . .

For the United States, this first defeat in our Nation’s history would result in a collapse of confidence in American leadership, not only in Asia but throughout the world. . . .

For these reasons, I rejected the recommendation that I should end the war by immediately withdrawing all of our forces. I chose instead to change American policy on both the negotiating front and battlefront.

In order to end a war fought on many fronts, I initiated a pursuit for peace on many fronts.

In a television speech on May 14, in a speech before the United Nations, and on a number of other occasions I set forth our peace proposals in great detail.

– We have offered the complete withdrawal of all outside forces within 1 year.

– We have proposed a cease-fire within 1 year.

– We have offered free elections under international supervision with the Communists participating in the organization and conduct of the elections as an organized political force. And the Saigon Government2 has pledged to accept the result of the elections. . . .

Hanoi3 has refused even to discuss our proposals. They demand our unconditional acceptance of their terms, which are that we withdraw all American forces immediately and unconditionally and that we overthrow the Government of South Vietnam as we leave. . . .

Well now, who is at fault?

It has become clear that the obstacle in negotiating an end to the war is not the President of the United States. It is not the South Vietnamese Government.

The obstacle is the other side’s absolute refusal to show the least willingness to join us in seeking a just peace. And it will not do so while it is convinced that all it has to do is to wait for our next concession, and our next concession after that one, until it gets everything it wants. . . .

Now let me turn, however, to a more encouraging report on another front.

At the time we launched our search for peace I recognized we might not succeed in bringing an end to the war through negotiation. I, therefore, put into effect another plan to bring peace – a plan which will bring the war to an end regardless of what happens on the negotiating front.

It is in line with a major shift in U.S. foreign policy which I described in my press conference at Guam on July 25. Let me briefly explain what has been described as the Nixon Doctrine – a policy which not only will help end the war in Vietnam, but which is an essential element of our program to prevent future Vietnams. . . .

. . . – First, the United States will keep all of its treaty commitments.

– Second, we shall provide a shield if a nuclear power threatens the freedom of a nation allied with us or of a nation whose survival we consider vital to our security.

– Third, in cases involving other types of aggression, we shall furnish military and economic assistance when requested in accordance with our treaty commitments. But we shall look to the nation directly threatened to assume the primary responsibility of providing the manpower for its defense.

. . .

The defense of freedom is everybody’s business – not just America’s business. And it is particularly the responsibility of the people whose freedom is threatened. In the previous administration, we Americanized the war in Vietnam. In this administration, we are Vietnamizing the search for peace.

. . . [T]he primary mission of our troops is [now] to enable the South Vietnamese forces to assume the full responsibility for the security of South Vietnam. . . .

. . . As South Vietnamese forces become stronger, the rate of American withdrawal can become greater. . . .

My fellow Americans, I am sure you can recognize from what I have said that we really only have two choices open to us if we want to end this war.

– I can order an immediate, precipitate withdrawal of all Americans from Vietnam without regard to the effects of that action.

– Or we can persist in our search for a just peace through a negotiated settlement if possible, or through continued implementation of our plan for Vietnamization if necessary – a plan in which we will withdraw all of our forces from Vietnam on a schedule in accordance with our program, as the South Vietnamese become strong enough to defend their own freedom.

I have chosen the second course.

It is not the easy way.

It is the right way . . .

And now I would like to address a word, if I may, to the young people of this Nation who are particularly concerned, and I understand why they are concerned, about this war.

I respect your idealism.

I share your concern for peace.

I want peace as much as you do . . .

I have chosen a plan for peace. I believe it will succeed.

If it does succeed, what the critics say now won’t matter. If it does not succeed, anything I say then won’t matter.

I know it may not be fashionable to speak of patriotism or national destiny these days. But I feel it is appropriate to do so on this occasion.

Two hundred years ago this Nation was weak and poor. But even then, America was the hope of millions in the world. Today we have become the strongest and richest nation in the world. And the wheel of destiny has turned so that any hope the world has for the survival of peace and freedom will be determined by whether the American people have the moral stamina and the courage to meet the challenge of free world leadership. . . .

And so tonight – to you, the great silent majority of my fellow Americans – I ask for your support. . . .

Let us be united for peace. Let us also be united against defeat. Because let us understand: North Vietnam cannot defeat or humiliate the United States. Only Americans can do that. . . .

Alcatraz Proclamation

November 20, 1969

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.