Introduction

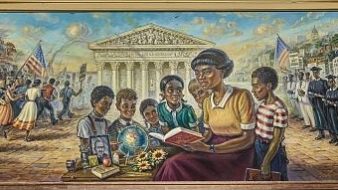

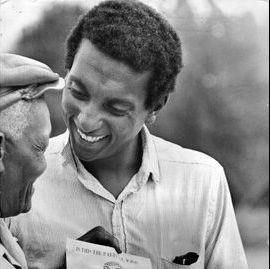

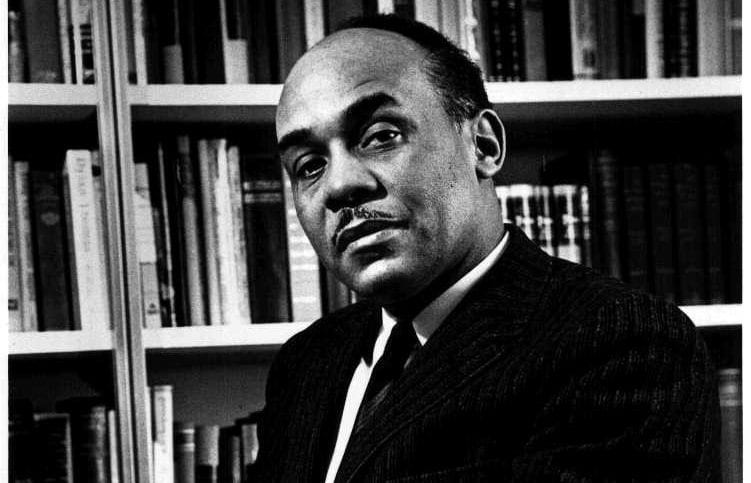

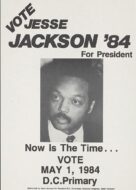

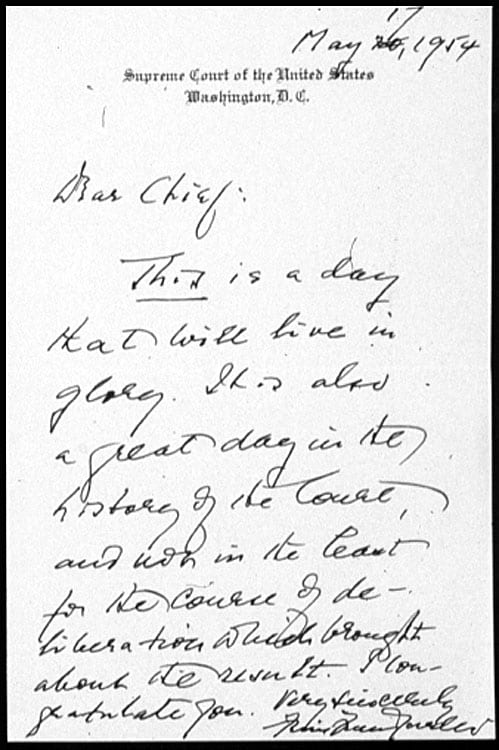

By 1966, Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) had achieved substantial success in the civil rights struggle. The violence and abuse black and white civil rights advocates had suffered at the hands of white southerners during the protest summers of 1961 and 1964 had raised national awareness of the persistent inequities of southern society. The March on Washington in 1963 had introduced a wide audience of Americans to the civil rights movement’s vision for an integrated America. The 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act were the federal government’s response to this grassroots effort; under these laws, no longer could states ignore black citizens’ rights and protections as codified in the 14th and 15th Amendments. De jure integration and equality had been achieved.

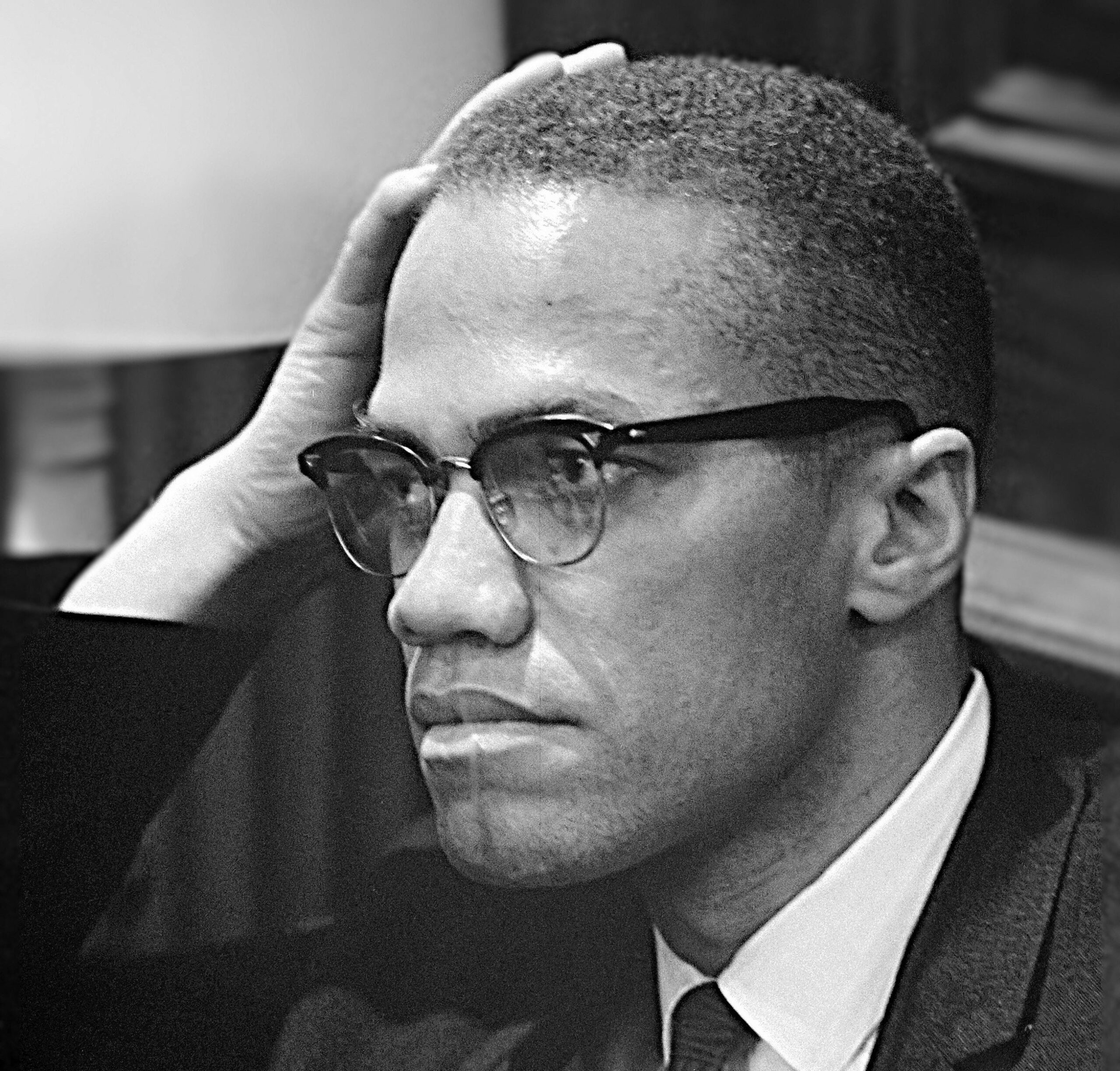

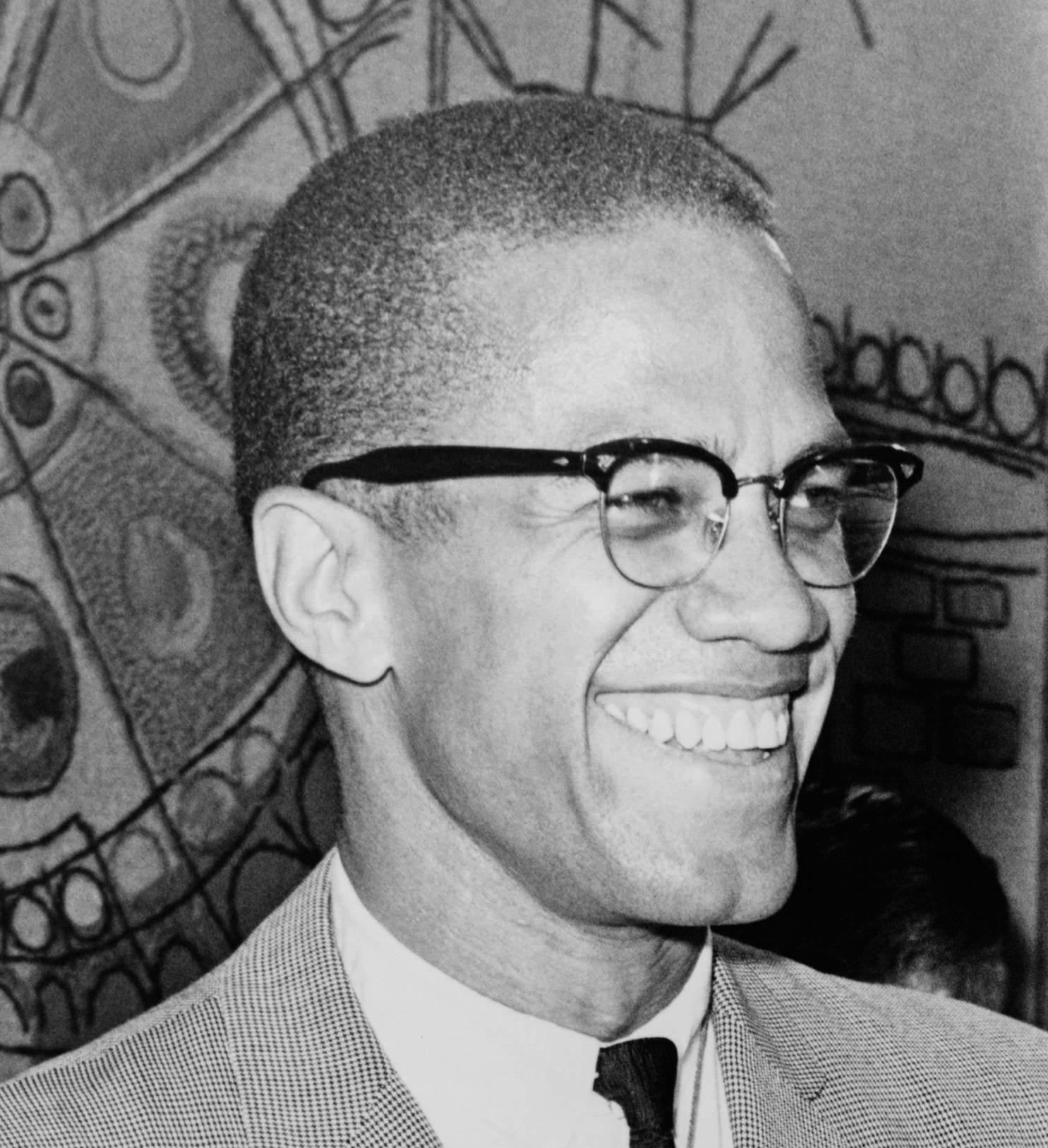

And yet, many white Americans vehemently resisted social reform, making de facto racism a continuing reality. Black Americans still struggled against social and economic oppression in the form of lower wages, unemployment, poor housing, and insufficient access to educational opportunities. In the face of such persistent inequality, many black Americans began to question Dr. King’s methods and goals. Black nationalism, with its embrace of self-defense and black self-determination, was appealing.

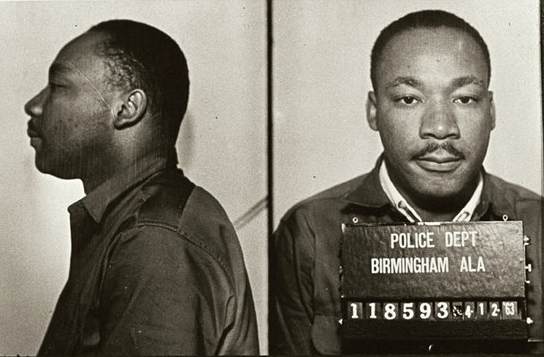

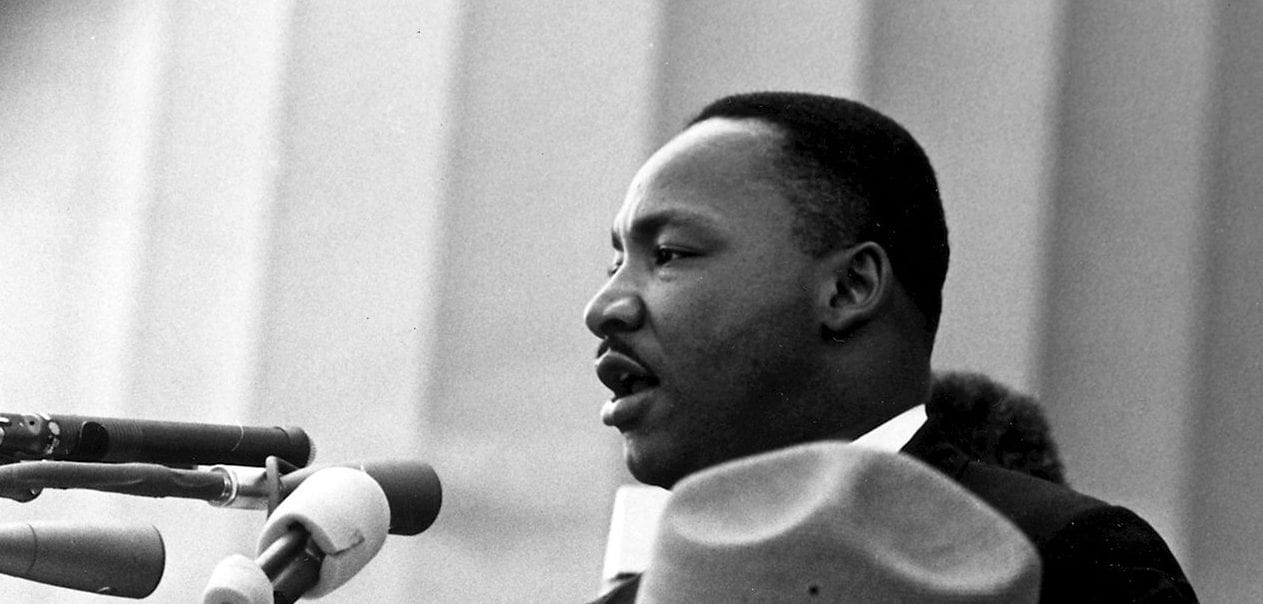

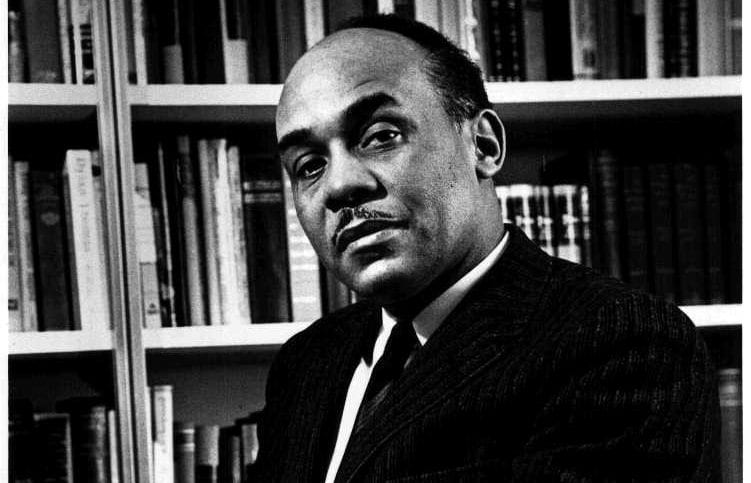

First printed in the October 1966 edition of Ebony, this essay is Dr. King’s response to the assertions of black nationalists. Refuting the need to meet physical aggression with self-defense, King renewed his call for nonviolent resistance. His passionate argument for a “beloved community” of white and black Americans echoes the aspirations of his “I Have a Dream” speech and challenges the creation of self-sufficient and independent black communities. As you read, note the various ways in which Dr. King promotes his vision of America while subtly discrediting the fledgling Black Power movement.

Source: “Nonviolence: The Only Road to Freedom,” in A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr., ed. James Melvin Washington (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1986), 54-61.

The year 1966 brought with it the first public challenge to the philosophy and strategy of nonviolence from within the ranks of the civil rights movement. Resolutions of self-defense and Black Power sounded forth from our friends and brothers. . . .

Indeed, there was much talk of violence. It was the same talk we have heard on the fringes of the nonviolent movement for the past ten years. It was the talk of fearful men, saying that they would not join the nonviolent movement because they would not remain nonviolent if attacked. Now the climate had shifted so that it was even more popular to talk of violence, . . . .

. . . [T]he Negro, even in his bitterest moments, is not intent on killing white men to be free. This does not mean that the Negro is a saint who abhors violence. Unfortunately, a check of the hospitals in any Negro community on any Saturday night will make you painfully aware of the violence within the Negro community. Hundreds of victims of shooting and cutting lie bleeding in the emergency rooms, but there is seldom if ever a white person who is the victim of Negro hostility. . . .

I am convinced that for practical as well as moral reasons, nonviolence offers the only road to freedom for my people. . . .

The hard cold facts of racial life in the world today indicate that the hope of the people of color in the world may well rest on the American Negro and his ability to reform the structures of racist imperialism from within and thereby turn the technology and wealth of the West to the task of liberating the world from want.

This is no time for romantic illusions about freedom and empty philosophical debate. . . . What is needed is . . . a tactical program which will bring the Negro into the mainstream of American life as quickly as possible. So far, this has only been offered by the nonviolent movement.

Our record of achievement through nonviolent action is already remarkable. . . .

The Question of Self-Defense

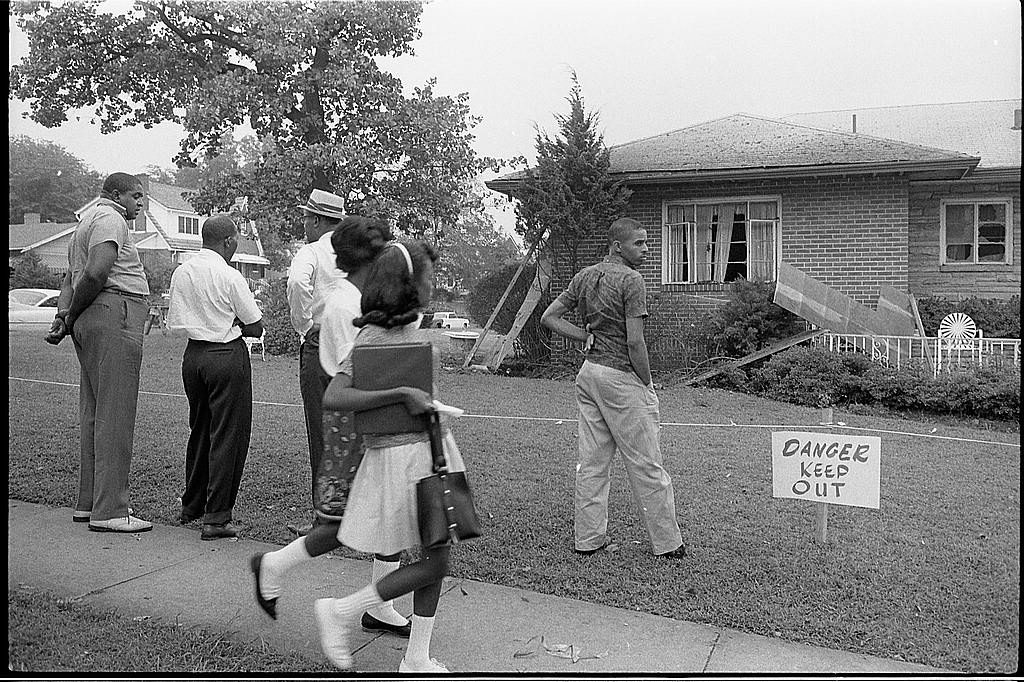

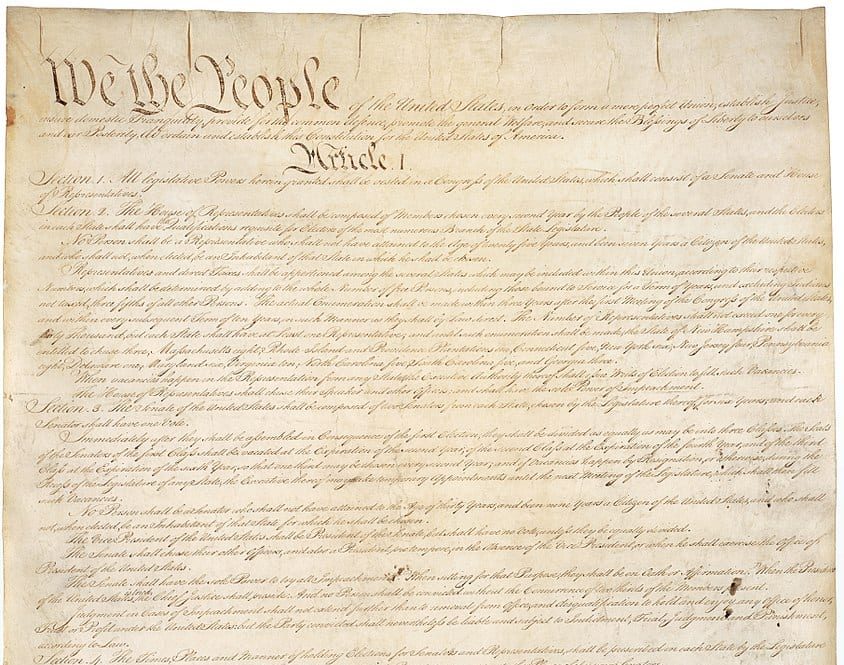

There are many people who very honestly raise the question of self-defense. . . . It goes without saying that people will protect their homes. This is a right guaranteed by the Constitution and respected even in the worst areas of the South. But the mere protection of one’s home and person against assault by lawless night riders does not provide any positive approach to the fears and conditions which produce violence. There must be some program for establishing law. . . .

In a nonviolent demonstration, self-defense must be approached from quite another perspective. One must remember that the cause of the demonstration is some exploitation or form of oppression that has made it necessary for men of courage and good will to demonstrate against the evil. For example, a demonstration against the evil of de facto school segregation is based on the awareness that a child’s mind is crippled daily by inadequate educational opportunity. The demonstrator agrees that it is better for him to suffer publicly for a short time to end the crippling evil of school segregation than to have generation after generation of children suffer in ignorance. . . .

It is always amusing to me when a Negro man says that he can’t demonstrate with us because if someone hit him he would fight back. Here is a man whose children are being plagued by rats and roaches, whose wife is robbed daily at overpriced ghetto food stores, who himself is working for about two-thirds the pay of a white person doing a similar job and with similar skills, and in spite of all this daily suffering it takes someone spitting on him or calling him a nigger to make him want to fight. . . .

Strategy for Change

The American racial revolution has been a revolution to “get in” rather than to overthrow. We want a share in the American economy, the housing market, the educational system and the social opportunities. The goal itself indicates that a social change in America must be nonviolent. . . .

The nonviolent strategy has been to dramatize the evils of our society in such a way that pressure is brought to bear against those evils by the forces of good will in the community and change is produced. . . .

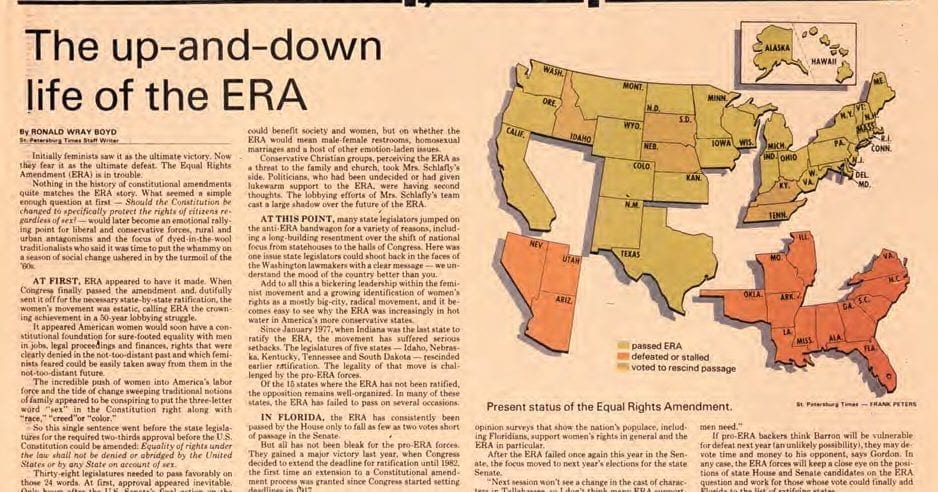

So far, we have had the Constitution backing most of the demands for change, and this has made our work easier, since we could be sure that the federal courts would usually back up our demonstrations legally. Now we are approaching areas where the voice of the Constitution is not clear. We have left the realm of constitutional rights and we are entering the area of human rights.

The Constitution assured the right to vote, but there is no such assurance of the right to adequate housing, or the right to an adequate income. And yet, in a nation which has a gross national product of 750 billion dollars a year, it is morally right to insist that every person has a decent house, an adequate education and enough money to provide basic necessities for one’s family. . . .

Techniques of the Future

When Negroes marched, so did the nation. . . . When marches are carefully organized around well-defined issues, they represent the power which Victor Hugo phrased as the most powerful force in the world, “an idea whose time has come.” . . . When the idea is a sound one, the cause a just one, and the demonstration a righteous one, change will be forthcoming. But if any of these conditions are not present, the power for change is missing . . . [A] group of ten thousand marching in anger against a police station and cussing out the chief of police will do very little to bring respect, dignity and unbiased law enforcement. Such a demonstration would only produce fear and bring about an addition of forces . . . .

. . . . [W]hen marching is seen as a part of a program to dramatize an evil, to mobilize the forces of good will, and to generate pressure and power for change, marches will continue to be effective. . . .

Along with the march as a weapon for change in our nonviolent arsenal must be listed the boycott. Basic to the philosophy of nonviolence is the refusal to cooperate with evil. There is nothing quite so effective as a refusal to cooperate economically with the forces and institutions which perpetuate evil in our communities. . . .

There is no easy way to create a world where men and women can live together, where each has his own job and house and where all children receive as much education as their minds can absorb. But if such a world is created in our lifetime, it will be done in the United States by Negroes and white people of good will. It will be accomplished by persons who have the courage to put an end to suffering by willingly suffering themselves rather than inflict suffering upon others. It will be done by rejecting the racism, materialism and violence that has characterized Western civilization and especially by working toward a world of brotherhood, cooperation and peace.

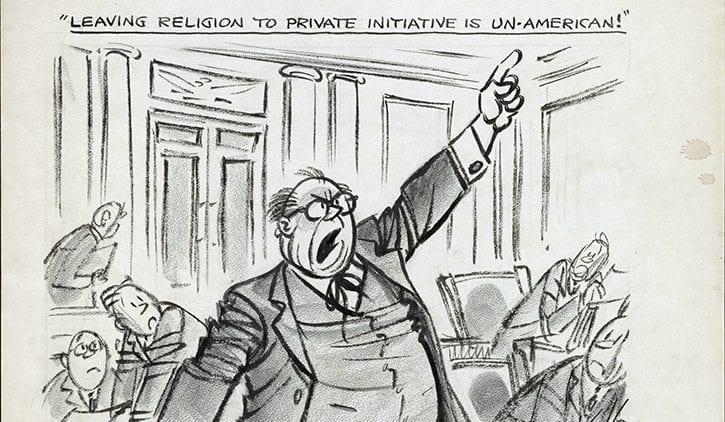

Zorach v. Clauson

February 1, 1952

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.