No related resources

Introduction

In South Carolina v. Katzenbach, the Supreme Court considered whether certain provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) could be sustained as a legitimate exercise of congressional authority under the enforcement clause of the Fifteenth Amendment (“the Congress shall have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation”). In passing the VRA, Congress sought to bring an end to laws and practices that state and local officials were using to restrict African Americans’ ability to vote. Some provisions of the VRA applied uniformly across the country. Other provisions applied to certain state and local governments and imposed particularly stringent restrictions on these jurisdictions.

Section 4 of the VRA set out a formula for determining which states and localities were covered by the latter provisions. As set out in the 1965 law, a state or local jurisdiction was subject to these strict rules if in 1964 it maintained a voting test or device such as a literacy test that restricted the ability to register and vote and if fewer than half of persons of voting age were registered to vote or cast votes in the 1964 presidential election. At the time the Supreme Court considered this challenge to the VRA, the formula led to seven states being covered entirely, along with portions of four other states. The VRA subjected these covered state and local jurisdictions to a number of restrictions, including suspending their use of literacy tests or similarly restrictive voting tests and requiring that these jurisdictions obtain clearance from federal officials before making any future changes to their voting laws (known as a preclearance provision).

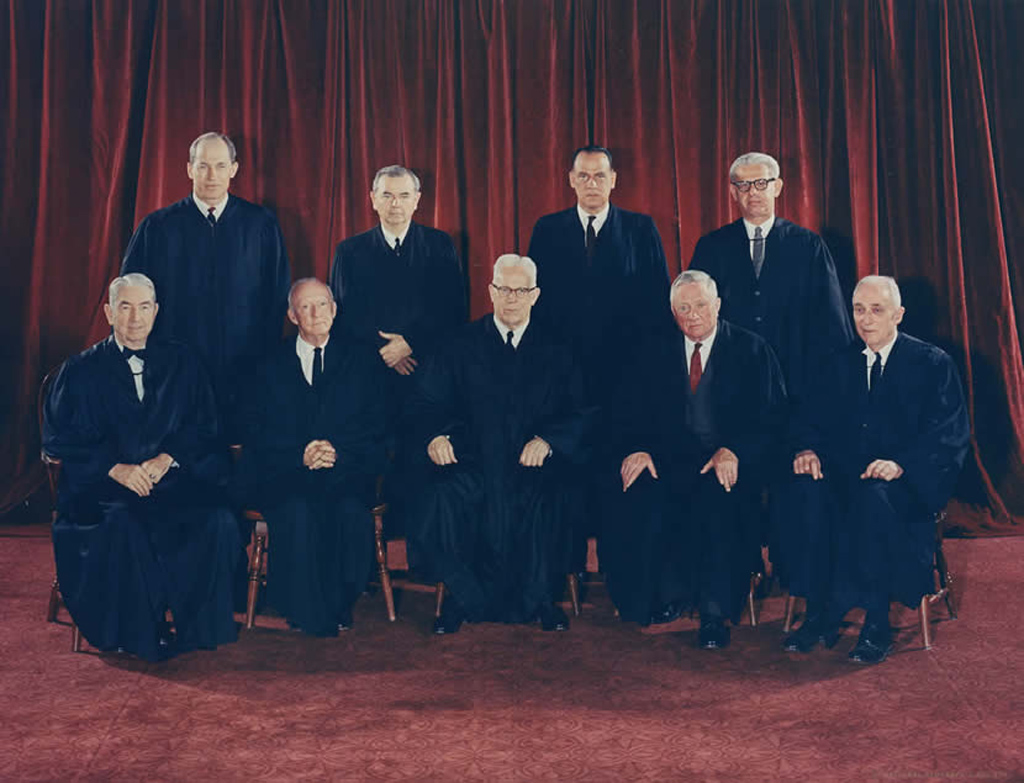

South Carolina and other covered states challenged these provisions on the ground that they exceeded Congress’ power under the Fifteenth Amendment and encroached on state sovereignty. The Supreme Court rejected this challenge. In his opinion for the Court, Chief Justice Earl Warren (1891–1974) concluded that Congress had plenary power to enforce the Fifteenth Amendment. Justice Hugo Black (1886–1971) dissented from the part of the Court’s opinion upholding the preclearance provision. Justice Black argued that the Fifteenth Amendment did not authorize Congress to require state governments to submit proposed laws for approval by federal officials, and that allowing Congress to exercise this power “approaches dangerously near to wiping the states out as useful and effective units in the government of our country.”

Nearly a half century after Congress enacted the VRA, and after passage of subsequent acts extending and revising these requirements in 1970, 1975, 1982, and 2006, the Supreme Court reconsidered their legitimacy in Shelby County v. Holder (2013). As part of VRA reauthorization laws in 1970 and 1975, Congress altered the Section 4 coverage formula, in part by taking account of additional discriminatory voting tests and devices whose use could lead a state or locality to be covered and also by taking account of data regarding state voter registration and turnout levels in the 1972 election. However, when the Supreme Court heard a challenge to these VRA provisions in 2013, the coverage formula had been unchanged for nearly four decades. In Shelby County v. Holder, the Supreme Court concluded that Congress’ failure to update the coverage formula and take account of registration and turnout data since the early 1970s was problematic. Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in his opinion for the Court that the formula “can no longer be used as a basis for subjecting jurisdictions to preclearance,” although “Congress may draft another formula based on current conditions.” During the decade after Shelby County v. Holder, however, Congress was not able to update the formula.

Source: 398 U.S. 301 (1966), https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/383/301.

Mr. Chief Justice WARREN delivered the opinion of the Court.

... South Carolina has filed a bill of complaint, seeking a declaration that selected provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 violate the federal Constitution, and asking for an injunction against enforcement of these provisions by the Attorney General....1

The Voting Rights Act was designed by Congress to banish the blight of racial discrimination in voting, which has infected the electoral process in parts of our country for nearly a century. The Act creates stringent new remedies for voting discrimination where it persists on a pervasive scale, and in addition the statute strengthens existing remedies for pockets of voting discrimination elsewhere in the country. Congress assumed the power to prescribe these remedies from [section 2] of the Fifteenth Amendment which authorizes the national legislature to effectuate by “appropriate” measures the constitutional prohibition against racial discrimination in voting. We hold that the sections of the Act which are properly before us are an appropriate means for carrying out Congress’ constitutional responsibilities and are consonant with all other provisions of the Constitution. We therefore deny South Carolina’s request that enforcement of these sections of the Act be enjoined.

The constitutional propriety of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 must be judged with reference to the historical experience which it reflects. Before enacting the measure, Congress explored with great care the problem of racial discrimination in voting. The House and Senate Committees on the Judiciary each held hearings for nine days and received testimony from a total of 67 witnesses. More than three full days were consumed discussing the bill on the floor of the House, while the debate in the Senate covered 26 days in all. At the close of these deliberations, the verdict of both chambers was overwhelming. The House approved the bill by a vote of 328–74, and the measure passed the Senate by a margin of 79–18.

Two points emerge vividly from the voluminous legislative history of the Act contained in the committee hearings and floor debates. First: Congress felt itself confronted by an insidious and pervasive evil which had been perpetuated in certain parts of our country through unremitting and ingenious defiance of the Constitution. Second: Congress concluded that the unsuccessful remedies which it had prescribed in the past would have to be replaced by sterner and more elaborate measures in order to satisfy the clear commands of the Fifteenth Amendment....

The Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution was ratified in 1870. Promptly thereafter Congress passed the Enforcement Act of 1870, which made it a crime for public officers and private persons to obstruct exercise of the right to vote. The statute was amended in the following year to provide for detailed federal supervision of the electoral process, from registration to the certification of returns. As the years passed and fervor for racial equality waned, enforcement of the laws became spotty and ineffective, and most of their provisions were repealed in 1894.2 The remnants have had little significance in the recently renewed battle against voting discrimination.

Meanwhile, beginning in 1890, the states of Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia enacted tests still in use which were specifically designed to prevent Negroes from voting. Typically, they made the ability to read and write a registration qualification and also required completion of a registration form. These laws were based on the fact that as of 1890 in each of the named states, more than two-thirds of the adult Negroes were illiterate while less than one-quarter of the adult whites were unable to read or write. At the same time, alternate tests were prescribed in all of the named states to assure that white illiterates would not be deprived of the franchise. These included grandfather clauses,3 property qualifications, “good character” tests, and the requirement that registrants “understand” or “interpret” certain matter.

The course of subsequent Fifteenth Amendment litigation in this Court demonstrates the variety and persistence of these and similar institutions designed to deprive Negroes of the right to vote. Grandfather clauses were invalidated in Guinn v. United States [1915] and Myers v. Anderson [1915]. Procedural hurdles were struck down in Lane v. Wilson [1939]. The white primary was outlawed in Smith v. Allwright [1944], and Terry v. Adams [1953]. Improper challenges were nullified in United States v. Thomas [1960]. Racial gerrymandering was forbidden by Gomillion v. Lightfoot [1960]. Finally, discriminatory application of voting tests was condemned in Schnell v. Davis [1949], Alabama v. United States [1962], and Louisiana v. United States [1965].

According to the evidence in recent Justice Department voting suits, the latter stratagem is now the principal method used to bar Negroes from the polls. Discriminatory administration of voting qualifications has been found in all eight Alabama cases, in all nine Louisiana cases, and in all nine Mississippi cases which have gone to final judgment. Moreover, in almost all of these cases, the courts have held that the discrimination was pursuant to a widespread “pattern or practice.” White applicants for registration have often been excused altogether from the literacy and understanding tests or have been given easy versions, have received extensive help from voting officials, and have been registered despite serious errors in their answers. Negroes, on the other hand, have typically been required to pass difficult versions of all the tests, without any outside assistance and without the slightest error. The good morals requirement is so vague and subjective that it has constituted an open invitation to abuse at the hands of voting officials. Negroes obliged to obtain vouchers from registered voters have found it virtually impossible to comply in areas where almost no Negroes are on the rolls.

In recent years, Congress has repeatedly tried to cope with the problem by facilitating case-by-case litigation against voting discrimination. The Civil Rights Act of 1957 authorized the Attorney General to seek injunctions against public and private interference with the right to vote on racial grounds. Perfecting amendments in the Civil Rights Act of 1960 permitted the joinder of states as parties defendant,4 gave the Attorney General access to local voting records, and authorized courts to register voters in areas of systematic discrimination. Title I of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 expedited the hearing of voting cases before three-judge courts and outlawed some of the tactics used to disqualify Negroes from voting in federal elections.

Despite the earnest efforts of the Justice Department and of many federal judges, these new laws have done little to cure the problem of voting discrimination. According to estimates by the Attorney General during hearings on the Act, registration of voting-age Negroes in Alabama rose only from 14.2% to 19.4% between 1958 and 1964; in Louisiana it barely inched ahead from 31.7% to 31.8% between 1956 and 1965; and in Mississippi it increased only from 4.4% to 6.4% between 1954 and 1964. In each instance, registration of voting-age whites ran roughly 50 percentage points or more ahead of Negro registration.

The previous legislation has proved ineffective for a number of reasons. Voting suits are unusually onerous to prepare, sometimes requiring as many as 6,000 man-hours spent combing through registration records in preparation for trial. Litigation has been exceedingly slow, in part because of the ample opportunities for delay afforded voting officials and others involved in the proceedings. Even when favorable decisions have finally been obtained, some of the states affected have merely switched to discriminatory devices not covered by the federal decrees or have enacted difficult new tests designed to prolong the existing disparity between white and Negro registration. Alternatively, certain local officials have defied and evaded court orders or have simply closed their registration offices to freeze the voting rolls. The provision of the 1960 law authorizing registration by federal officers has had little impact on local maladministration because of its procedural complexities....

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 reflects Congress’ firm intention to rid the country of racial discrimination in voting. The heart of the Act is a complex scheme of stringent remedies aimed at areas where voting discrimination has been most flagrant. Section 4(a)–(d) lays down a formula defining the states and political subdivisions to which these new remedies apply. The first of the remedies, contained in [section] 4(a), is the suspension of literacy tests and similar voting qualifications for a period of five years from the last occurrence of substantial voting discrimination. Section 5 prescribes a second remedy, the suspension of all new voting regulations pending review by federal authorities to determine whether their use would perpetuate voting discrimination. The third remedy, covered in [sections] 6(b), 7, 9, and 13(a), is the assignment of federal examiners on certification by the Attorney General to list qualified applicants who are thereafter entitled to vote in all elections....

These provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 are challenged on the fundamental ground that they exceed the powers of Congress and encroach on an area reserved to the states by the Constitution....

The ground rules for resolving this question are clear. The language and purpose of the Fifteenth Amendment, the prior decisions construing its several provisions, and the general doctrines of constitutional interpretation, all point to one fundamental principle. As against the reserved powers of the states, Congress may use any rational means to effectuate the constitutional prohibition of racial discrimination in voting....

Section 1 of the Fifteenth Amendment declares that “(t)he right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” This declaration has always been treated as self-executing and has repeatedly been construed, without further legislative specification, to invalidate state voting qualifications or procedures which are discriminatory on their face or in practice....

The basic test to be applied in a case involving [section] 2 of the Fifteenth Amendment is the same as in all cases concerning the express powers of Congress with relation to the reserved powers of the states. Chief Justice Marshall laid down the classic formulation, 50 years before the Fifteenth Amendment was ratified:

Let the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the Constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited, but consist with the letter and spirit of the constitution, are constitutional.5

The Court has subsequently echoed his language in describing each of the Civil War Amendments:

Whatever legislation is appropriate, that is, adapted to carry out the objects the amendments have in view, whatever tends to enforce submission to the prohibitions they contain, and to secure to all persons the enjoyment of perfect equality of civil rights and the equal protection of the laws against state denial or invasion, if not prohibited, is brought within the domain of congressional power.6

This language was again employed, nearly 50 years later, with reference to Congress’ related authority under [section] 2 of the Eighteenth Amendment.7

We therefore reject South Carolina’s argument that Congress may appropriately do no more than to forbid violations of the Fifteenth Amendment in general terms—that the task of fashioning specific remedies or of applying them to particular localities must necessarily be left entirely to the courts. Congress is not circumscribed by any such artificial rules under [section] 2 of the Fifteenth Amendment. In the oft-repeated words of Chief Justice Marshall, referring to another specific legislative authorization in the Constitution, “This power, like all others vested in Congress, is complete in itself, may be exercised to its utmost extent, and acknowledges no limitations, other than are prescribed in the constitution.”8...

After enduring nearly a century of widespread resistance to the Fifteenth Amendment, Congress has marshalled an array of potent weapons against the evil, with authority in the Attorney General to employ them effectively. Many of the areas directly affected by this development have indicated their willingness to abide by any restraints legitimately imposed upon them. We here hold that the portions of the Voting Rights Act properly before us are a valid means for carrying out the commands of the Fifteenth Amendment. Hopefully, millions of non-white Americans will now be able to participate for the first time on an equal basis in the government under which they live. We may finally look forward to the day when truly “(t)he right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”...

Mr. Justice BLACK, concurring and dissenting.

I agree with substantially all of the Court’s opinion sustaining the power of Congress under [section] 2 of the Fifteenth Amendment to suspend state literacy tests and similar voting qualifications and to authorize the Attorney General to secure the appointment of federal examiners to register qualified voters in various sections of the country....

Though, as I have said, I agree with most of the Court’s conclusions, I dissent from its holding that every part of [section] 5 of the Act is constitutional. Section 4(a), to which [section] 5 is linked, suspends for five years all literacy tests and similar devices in those states coming within the formula of [section] 4(b). Section 5 goes on to provide that a state covered by [section] 4(b) can in no way amend its constitution or laws relating to voting without first trying to persuade the Attorney General of the United States or the Federal District Court for the District of Columbia that the new proposed laws do not have the purpose and will not have the effect of denying the right to vote to citizens on account of their race or color. I think this section is unconstitutional on at least two grounds....

My second and more basic objection to [section] 5 is that Congress has here exercised its power under [section] 2 of the Fifteenth Amendment through the adoption of means that conflict with the most basic principles of the Constitution. As the Court says the limitations of the power granted under [section] 2 are the same as the limitations imposed on the exercise of any of the powers expressly granted Congress by the Constitution. The classic formulation of these constitutional limitations was stated by Chief Justice Marshall when he said in McCulloch v. State of Maryland, “Let the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the Constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited, but consist with the letter and spirit of the Constitution, are constitutional” (emphasis added). Section 5, by providing that some of the states cannot pass state laws or adopt state constitutional amendments without first being compelled to beg federal authorities to approve their policies, so distorts our constitutional structure of government as to render any distinction drawn in the Constitution between state and federal power almost meaningless. One of the most basic premises upon which our structure of government was founded was that the federal government was to have certain specific and limited powers and no others, and all other power was to be reserved either “to the states respectively, or to the people.”9 Certainly if all the provisions of our Constitution which limit the power of the federal government and reserve other power to the states are to mean anything, they mean at least that the states have power to pass laws and amend their constitutions without first sending their officials hundreds of miles away to beg federal authorities to approve them. Moreover, it seems to me that [section] 5 which gives federal officials power to veto state laws they do not like is in direct conflict with the clear command of our Constitution that “[t]he United States shall guarantee to every state in this Union a republican form of government.”10 I cannot help but believe that the inevitable effect of any such law which forces any one of the states to entreat federal authorities in faraway places for approval of local laws before they can become effective is to create the impression that the state or states treated in this way are little more than conquered provinces. And if one law concerning voting can make the states plead for this approval by a distant federal court or the United States Attorney General, other laws on different subjects can force the states to seek the advance approval not only of the Attorney General but of the President himself or any other chosen members of his staff. It is inconceivable to me that such a radical degradation of state power was intended in any of the provisions of our Constitution or its amendments. Of course I do not mean to cast any doubt whatever upon the indisputable power of the federal government to invalidate a state law once enacted and operative on the ground that it intrudes into the area of supreme federal power. But the federal government has heretofore always been content to exercise this power to protect federal supremacy by authorizing its agents to bring lawsuits against state officials once an operative state law has created an actual case and controversy. A federal law which assumes the power to compel the states to submit in advance any proposed legislation they have for approval by federal agents approaches dangerously near to wiping the states out as useful and effective units in the government of our country. I cannot agree to any constitutional interpretation that leads inevitably to such a result.

I see no reason to read into the Constitution meanings it did not have when it was adopted and which have not been put into it since. The proceedings of the original Constitutional Convention show beyond all doubt that the power to veto or negative state laws was denied Congress.11 On several occasions proposals were submitted to the convention to grant this power to Congress. These proposals were debated extensively and on every occasion when submitted for vote they were overwhelmingly rejected. The refusal to give Congress this extraordinary power to veto state laws was based on the belief that if such power resided in Congress the states would be helpless to function as effective governments. Since that time neither the Fifteenth Amendment nor any other amendment to the Constitution has given the slightest indication of a purpose to grant Congress the power to veto state laws either by itself or its agents. Nor does any provision in the Constitution endow the federal courts with power to participate with state legislative bodies in determining what state policies shall be enacted into law. The judicial power to invalidate a law in a case or controversy after the law has become effective is a long way from the power to prevent a state from passing a law. I cannot agree with the Court that Congress—denied a power in itself to veto a state law—can delegate this same power to the Attorney General or the District Court for the District of Columbia. For the effect on the states is the same in both cases—they cannot pass their laws without sending their agents to the City of Washington to plead to federal officials for their advance approval....

- 1. Nicholas Katzenbach (1922–2012).

- 2. The Civil Rights Repeal Act, 28 Stat. 3 (1894). The Democratic Party gained control of both houses of Congress and the presidency (Grover Cleveland) in the election of 1892 for the first time since 1858.

- 3. A “grandfather clause” excludes certain people or things from the control of a law because they previously had the right or carried out the action governed by the law.

- 4. Allowed states to be sued in voting rights cases.

- 5. Chief Justice Warren’s note: McCulloch v. Maryland [1819].

- 6. Chief Justice Warren’s note: Ex parte Virginia [1879].

- 7. Chief Justice Warren’s note: James Everard’s Breweries v. Day [1924].

- 8. Chief Justice Warren’s note: Gibbons v. Ogden [1824].

- 9. The Tenth Amendment.

- 10. Article IV, section 4.

- 11. Federal Constitutional Convention, Debate on National Veto of State Laws, June 8, 1787

Miranda v. Arizona

June 13, 1966

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.