No related resources

Introduction

In South Dakota v. Dole, the Supreme Court considered whether Congress could require states to raise their drinking age to twenty-one or lose 5 percent of their federal highway funds. Prior to passage of the National Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984, signed into law by President Ronald Reagan, states maintained a variety of drinking ages, ranging from eighteen to twenty-one; some set different ages for purchasing different types of alcohol. South Dakota, which permitted individuals to purchase beer and wine at the age of nineteen, argued that the law was not authorized by Congress’ spending power (Article I, section 8, clause 1) and (in an argument the majority of the Court did not see a need to resolve) violated the Twenty-First Amendment.

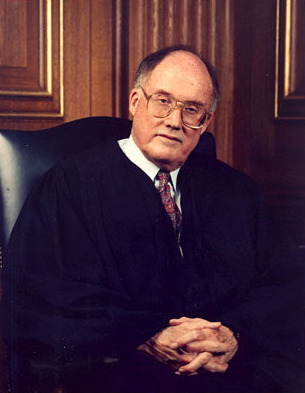

The Supreme Court sustained Congress’ power to enact the requirement, and in the process established a framework for determining when Congress is validly exercising its spending power, a vehicle that Congress has increasingly relied on to accomplish policy goals that it lacks the power to achieve directly. In his opinion for the Court, Chief Justice William Rehnquist (1924–2005) explained the four elements of this framework. Additionally—and this was the key point of contention in this case—Congress could not offer a financial incentive “so coercive as to pass the point at which ‘pressure turns into compulsion.’” The Court concluded that the National Minimum Drinking Age Act did not run afoul of any of these requirements.

Source: 483 U.S. 203, https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/483/203.

Chief Justice REHNQUIST delivered the opinion of the Court.

Petitioner South Dakota permits persons 19 years of age or older to purchase beer containing up to 3.2% alcohol. In 1984 Congress enacted 23 U.S.C. § 158, which directs the secretary of transportation to withhold a percentage of federal highway funds otherwise allocable from states “in which the purchase or public possession ... of any alcoholic beverage by a person who is less than twenty-one years of age is lawful.” The state sued in United States District Court seeking a declaratory judgment that § 158 violates the constitutional limitations on congressional exercise of the spending power and violates the Twenty-First Amendment to the United States Constitution....

These arguments present questions of the meaning of the Twenty-First Amendment, the bounds of which have escaped precise definition. Despite the extended treatment of the question by the parties, however, we need not decide in this case whether that amendment would prohibit an attempt by Congress to legislate directly a national minimum drinking age. Here, Congress has acted indirectly under its spending power to encourage uniformity in the states’ drinking ages. As we explain below, we find this legislative effort within constitutional bounds even if Congress may not regulate drinking ages directly.

The Constitution empowers Congress to “lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States.” Incident to this power, Congress may attach conditions on the receipt of federal funds, and has repeatedly employed the power “to further broad policy objectives by conditioning receipt of federal moneys upon compliance by the recipient with federal statutory and administrative directives.”1 ... The breadth of this power was made clear in United States v. Butler (1936), where the Court, resolving a longstanding debate over the scope of the spending clause, determined that “the power of Congress to authorize expenditure of public moneys for public purposes is not limited by the direct grants of legislative power found in the Constitution.” Thus, objectives not thought to be within Article I’s “enumerated legislative fields,” may nevertheless be attained through the use of the spending power and the conditional grant of federal funds.

The spending power is of course not unlimited, but is instead subject to several general restrictions articulated in our cases. The first of these limitations is derived from the language of the Constitution itself: the exercise of the spending power must be in pursuit of “the general welfare.” In considering whether a particular expenditure is intended to serve general public purposes, courts should defer substantially to the judgment of Congress. Second, we have required that if Congress desires to condition the states’ receipt of federal funds, it “must do so unambiguously ... , enabl[ing] the states to exercise their choice knowingly, cognizant of the consequences of their participation.” Third, our cases have suggested (without significant elaboration) that conditions on federal grants might be illegitimate if they are unrelated “to the federal interest in particular national projects or programs.” Finally, we have noted that other constitutional provisions may provide an independent bar to the conditional grant of federal funds.

South Dakota does not seriously claim that § 158 is inconsistent with any of the first three restrictions mentioned above. We can readily conclude that the provision is designed to serve the general welfare, especially in light of the fact that “the concept of welfare or the opposite is shaped by Congress.” Congress found that the differing drinking ages in the states created particular incentives for young persons to combine their desire to drink with their ability to drive, and that this interstate problem required a national solution. The means it chose to address this dangerous situation were reasonably calculated to advance the general welfare. The conditions upon which states receive the funds, moreover, could not be more clearly stated by Congress. And the state itself, rather than challenging the germaneness of the condition to federal purposes, admits that it “has never contended that the congressional action was ... unrelated to a national concern in the absence of the Twenty-First Amendment.” Indeed, the condition imposed by Congress is directly related to one of the main purposes for which highway funds are expended—safe interstate travel. This goal of the interstate highway system had been frustrated by varying drinking ages among the states. A presidential commission appointed to study alcohol-related accidents and fatalities on the nation’s highways concluded that the lack of uniformity in the states’ drinking ages created “an incentive to drink and drive” because “young persons commut[e] to border states where the drinking age is lower.” By enacting § 158, Congress conditioned the receipt of federal funds in a way reasonably calculated to address this particular impediment to a purpose for which the funds are expended....

Our decisions have recognized that in some circumstances the financial inducement offered by Congress might be so coercive as to pass the point at which “pressure turns into compulsion.”2 Here, however, Congress has directed only that a state desiring to establish a minimum drinking age lower than 21 lose a relatively small percentage of certain federal highway funds. Petitioner contends that the coercive nature of this program is evident from the degree of success it has achieved. We cannot conclude, however, that a conditional grant of federal money of this sort is unconstitutional simply by reason of its success in achieving the congressional objective.

When we consider, for a moment, that all South Dakota would lose if she adheres to her chosen course as to a suitable minimum drinking age is 5% of the funds otherwise obtainable under specified highway grant programs, the argument as to coercion is shown to be more rhetoric than fact....

Here Congress has offered relatively mild encouragement to the states to enact higher minimum drinking ages than they would otherwise choose. But the enactment of such laws remains the prerogative of the states not merely in theory but in fact. Even if Congress might lack the power to impose a national minimum drinking age directly, we conclude that encouragement to state action found in § 158 is a valid use of the spending power....

A Colorblind Society Remains an Aspiration

August 15, 1987

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.