The Cold War

The Cold War lasted for almost a half-century, from the mid-1940s through the early 1990s. The conflict’s origins were deep and complex, but the root cause of this persistent hostility between the United States and the Soviet Union was ideology. The United States is a constitutional democracy. This form of government, along with capitalism, abundant resources, and advanced industries, made the nation an unmatched global power by the end of World War II. The Soviet Union (officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics or U.S.S.R.) was the world’s greatest communist state. Arising amid the growing pains of industrialism in the West, communism is an ideology antithetical to democracy and capitalism. Communism seeks to erase the class lines inherent in capitalist societies. To accomplish this goal, the Soviet Union completely denied or severely restricted its citizens’ basic rights: freedom of speech and press, property ownership, and the free practice of religion. American democracy was imperfect – at the start of the Cold War, racial segregation and prejudice denied millions of African Americans their rights – but the principles of individual freedom and equality made possible movements to dismantle state-sanctioned discrimination during the Cold War itself. In the Soviet Union, totalitarian rule in service to communism rarely wavered.

Yet these vastly different nations had joined together during World War II to fight a common foe, Nazi Germany. This fact alone reminds us of the complexity of the Cold War. The alliance did not abate the possibility of postwar conflict. It increased it. Distrust and suspicion based on each nation’s respective actions pitted the two superpowers against one another. Both sought to spread their respective ideologies and forms of government. As they competed for allies, they pulled much of the world into the conflict. The label “Cold War” refers to the fact that the United States and the Soviet Union never directly went to war with one another, but proxy wars in Korea, Vietnam, and Afghanistan, among many places, demonstrate the long and devastating reach of the conflict.

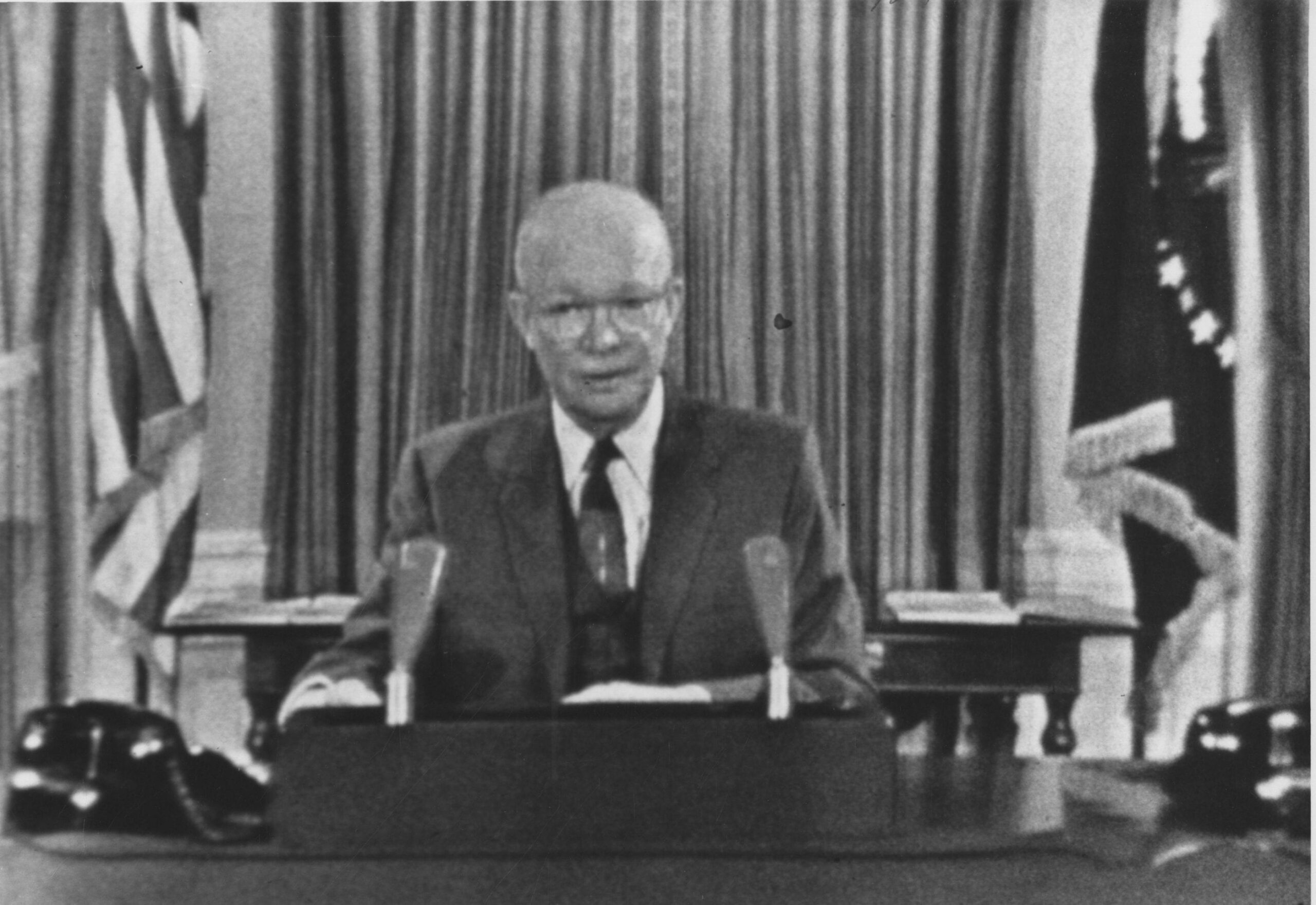

The Cold War did more than determine international alliances and cause wars; it also impacted the diplomacy, military, economy, politics, culture, and society of the superpowers and dozens of other nations. In the United States, the fear of communism led numerous states to require their public employees, including teachers, to take loyalty oaths. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, a committed Cold Warrior, nonetheless used his Farewell Address to warn his fellow citizens that a growing “military-industrial complex” and dependency on the federal government for scientific and technological innovation (both results of the Cold War) threatened self-government and individual liberty.

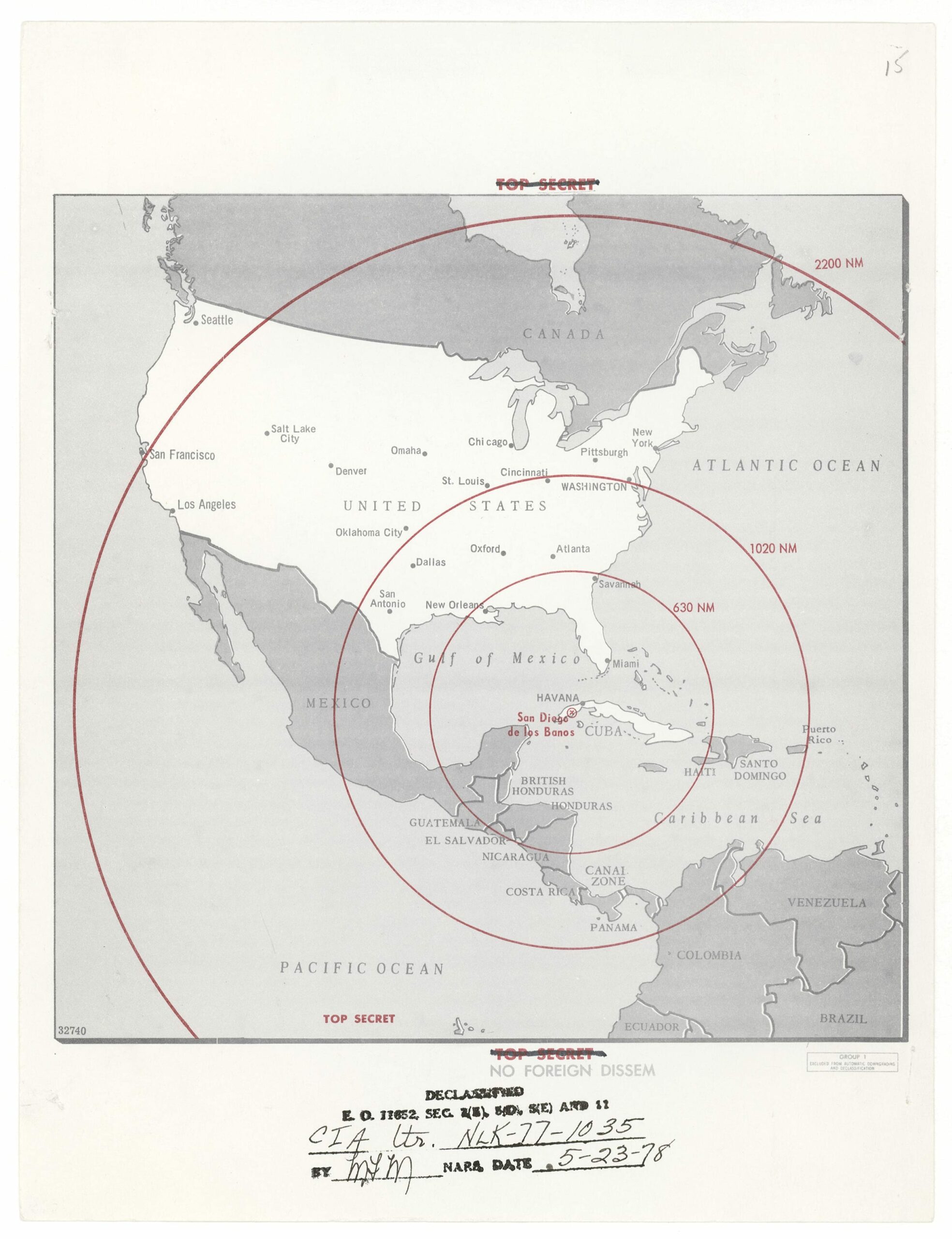

The costs of the Cold War were enormous; so, too, its hazards. The United States spent trillions of dollars to advance its Cold War policies and programs. Just one of the proxy wars, the Korean War (See Truman and Macarthur), took the lives of more than 1.2 million combatants (including 36,574 Americans), yet the three-year war ended precisely where it started, with a communist regime north of the 38th parallel on the Korean peninsula. In Southeast Asia, the United States committed itself to an unsuccessful war to prevent the unification of Vietnam under communism (See Rusk and McNamara, LBJ, the “Joint Resolution of Congress,” LBJ, and Nixon). The difficulties of forcing Vietnam’s civil conflict to fit the policy of containment raised concerns within the government (See Ball) and led some Americans, including President Jimmy Carter, to ask if the United States had undermined its own principles in fighting this war (See “Statement by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee on the War in Vietnam” (1966) and Carter). Finally, the arsenals of nuclear weapons amassed by the United States and the Soviet Union (as well as other nations) held the power to kill a majority of the world’s population and likely destroy the planet’s ability to sustain life. The 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, a showdown between the United States and the Soviet Union, almost triggered a nuclear war (See Kennedy, “Minutes of the Meeting of the Special Group on Operation MONGOOSE” (1962), “Central Intelligence Agency, Soviet Reactions to Certain U.S. Courses of Action on Cuba” (1962), and Kennedy).

Acutely aware of the ultimate danger of the Cold War, Soviet and American leaders often worked to ease tensions. In 1959, the United States hosted an exhibit in Moscow on American society and industry. Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev accompanied Vice President Richard Nixon on a tour of the exhibit, leading to a spirited but friendly exchange between the two men about the merits and flaws of communism, capitalism, and democracy. Both leaders stood their ground during the Kitchen Debate (so-called because one back-and-forth took place in a model of an American kitchen), but they also agreed that mutual understanding inhibited conflict. In 1963, the United States and the Soviet Union, along with other nations, drafted and signed a nuclear test ban treaty in hopes that the quest for more powerful nuclear arms could be slowed. In 1972, Nixon, now president, visited communist China as part of a strategy known as détente, a French word that in this context means an easing of tensions (See “Joint Statement Following Discussions with Leaders of the People’s Republic of China” (1972)). The historic meeting enabled the United States and China to soon restore diplomatic and trade relations.

However, the entrenched differences between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies meant that crises could erupt at any time. In 1976, U.S. national security policymakers discussed various ways, including military action, to disrupt the foreign policy of communist Cuba, but they also noted the danger of such actions provoking the Soviet Union (See “Washington Special Actions Group, Meeting on Cuba” (1976)). In 1979, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan incurred a strong response from the United States (See Carter). The era of détente abruptly ended.

During the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan was determined to bring the Cold War to a peaceful end. Though critics charged that he was intensifying the Cold War by committing the United States to a massive military buildup, Reagan countered that a strengthened defense, including an experimental anti-missile program known as the Strategic Defense Initiative, advanced peace by deterring communist aggression. Reagan also drafted nuclear arms reduction agreements with the Soviet Union. As the president made clear in a 1987 speech, the ultimate goal of the United States and its allies was not simply to manage the Cold War – it was to peacefully advance freedom and democracy, sweeping communism aside in the process (See Reagan). By the late 1980s, democratic movements in Poland and Czechoslovakia, both communist nations, hinted that the Cold War might well be at a turning point.

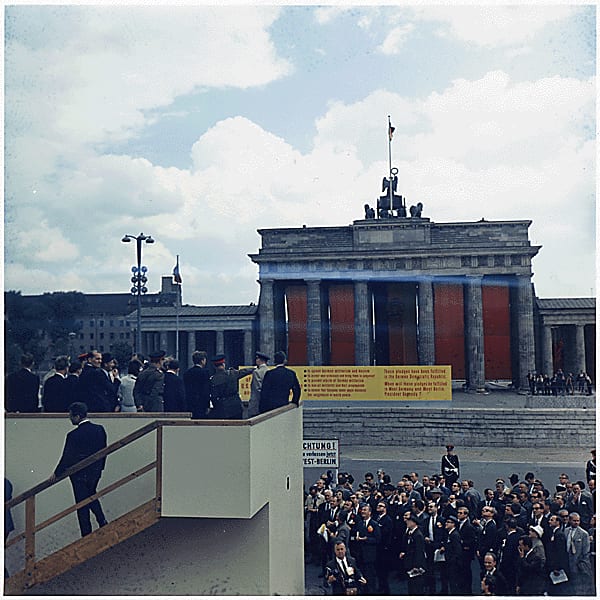

Indeed, aware that drastic changes were needed to save communism, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev undertook major internal reforms and, just as important, significantly changed the terms of Soviet control of Eastern Europe’s communist states. In 1956, the Soviet Union had crushed a democratic uprising in communist Hungary (See Eisenhower); thirty years later, Gorbachev announced that the Soviet Union would not use force to intervene in the domestic affairs of communist nations. In 1989, Gorbachev spoke hopefully of Europe as a “common home” in which communist nations worked peacefully with democratic countries to solve mutual problems. U.S. intelligence analysts cautioned that the Soviet Union remained a threat (See “National Security Directive 23” (1989)), yet communism was faltering and falling. Later that year, the Berlin Wall – the most visible sign of the division between the communist and free worlds in Europe (See Kennedy and Reagan) – came down, and the joyous meeting of Berliners on this previously heavily guarded border signified the end of the Cold War (See Bush and Kohl).

The purpose of this collection is to provide teachers with a selection of primary sources that document the multi-faceted Cold War. A variety of sources are used to represent, as much as possible, the conflict’s most significant developments and patterns. The addresses and statements of Cold War-era presidents offer insight into the principles and purposes of U.S. policies. Congressional resolutions and testimony before Congress show the key role of the legislative branch. Declassified documents from the National Security Agency, Department of State, and National Security Council offer a glimpse into the planning of covert operations, management of international propaganda, and Soviet espionage in the United States, among other topics. Although a majority of the sources relate to the diplomatic, military, and political sides of the Cold War, select documents provide perspective on the conflict’s effects on American society. The sources are presented in chronological order, but a thematic table of contents is also provided (Appendix A), so that users may quickly find documents of interest.

Acknowledgments

Several people assisted me in the preparation of this collection, and I’m grateful for their contributions. Eric Pullin and John Moser provided excellent suggestions on the selection of documents. Ali Brosky ably converted and formatted documents for me. Series editor David Tucker offered expert guidance and editing and had immediate answers for all my questions.

Asia, U.S. policies for: “Crisis in Asia,” “Report to the American People on Korea,” “Address to Congress,” “A Policy of Boldness,” “Report to President Kennedy on South Vietnam,” “Special Message to the Congress on the U.S. Policy in Southeast Asia,” “Joint Resolution of Congress,” “Peace Without Conquest,” “Compromise Solution for South Vietnam,” “Statement by the SNCC on the War in Vietnam,” “Address to the Nation on the War in Vietnam,” “Discussions with Leaders of the People’s Republic of China,” and “Address to the Nation Announcing the Conclusion of an Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam.”

Berlin Wall: “Remarks in the Rudolph Wilde Platz,” “Remarks on East-West Relations at the Brandenburg Gate in West Berlin,” and “Telephone Conversation.”

Chile: “Telephone Conversation about Chile,” and “Telephone Conversation about Chile.”

China: “Crisis in Asia–An Examination of U.S. Policy,” “Report to the American People on Korea,” “Address to Congress,” and “Joint Statement Following Discussions with Leaders of the People’s Republic of China.”

Civil Defense: “Organized Evacuation of Civilian Populations in Civil Defense.”

Civil Rights: “The Negro in American Life (Guidance for the Voice of America),” “Testimony before the House Committee on Un-American Activities,” “The Port Huron Statement,” and “Statement by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee on the War in Vietnam”

Cold War, end of: “Address to the Nation on Defense and National Security,” “Remarks on East-West Relations at the Brandenburg Gate in West Berlin,” “National Security Directive 23, ‘United States Relations with the Soviet Union,'” and “Telephone Conversation.”

Communism, Threat of: “The Long Telegram,” “Special Message to the Congress on Greece and Turkey (The Truman Doctrine),” “European Initiative Essential to Economic Recovery (the Marshall Plan).” “Address to the League of Women Voters, Wheeling, West Virginia” “United States Objectives and Programs for National Security (NSC 68),” “Declaration of Conscience,” “Report to the American People on Korea,” “Address to Congress,” “A Policy of Boldness,” “Farewell Address,” “Farewell Address,” “Inaugural Address,” “Peace Without Conquest,” and “Address to the Nation on the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan,” and “Address to the Nation on Defense and National Security”

Containment: “The Long Telegram,” “Special Message to the Congress on Greece and Turkey (The Truman Doctrine),” “European Initiative Essential to Economic Recovery (the Marshall Plan),” “A Policy of Boldness,” “Farewell Address,” and “Report to President Kennedy on South Vietnam.”

Covert Operations: “NSC 5412/2, Covert Operations,” “Minutes of the Meeting of the Special Group (Augmented) on Operation MONGOOSE,” “Telephone Conversation about Chile”, “Telephone Conversation about Chile,” “Meeting on Cuba,” and “Address at Commencement Exercises at the University of Notre Dame.”

Cuban Missile Crisis: “Statement on Cuba,” “Minutes of the Meeting of the Special Group (Augmented) on Operation MONGOOSE,” “Soviet Reactions to Certain U.S. Courses of Action on Cuba,” and “Radio and Television Report to the American People on the Soviet Arms Buildup in Cuba.”

Democratization: “Special Message to the Congress on Greece and Turkey (The Truman Doctrine),” “United States Objectives and Programs for National Security (NSC 68),” “A Policy of Boldness,” “Farewell Address,” “Remarks in the Rudolph Wilde Platz,” “Peace Without Conquest,” “Address at Commencement Exercises at the University of Notre Dame,” and “National Security Directive 23, ‘United States Relations with the Soviet Union'”

Domestic Anticommunism (McCarthyism): “Address to the League of Women Voters, Wheeling, West Virginia,” “Declaration of Conscience,” “Sentencing of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg,” and “Testimony before the House Committee on Un-American Activities,”

Economic policies: “European Initiative Essential to Economic Recovery (the Marshall Plan),” “United States Objectives and Programs for National Security (NSC 68),” and “The Kitchen Debate,” “Telephone Conversation.”

Espionage: “Address to the League of Women Voters, Wheeling, West Virginia,” “Declaration of Conscience,” and “Sentencing of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg”

Europe: “Special Message to the Congress on Greece and Turkey (The Truman Doctrine),” “European Initiative Essential to Economic Recovery (the Marshall Plan),” “A Policy of Boldness,” “Radio and Television Report to the American People on the Developments in Eastern Europe and the Middle East,” “Remarks in the Rudolph Wilde Platz,” “Remarks on East-West Relations at the Brandenburg Gate in West Berlin,” “National Security Directive 23, ‘United States Relations with the Soviet Union,'” and “Telephone Conversation.”

Hungarian Uprising (1956): “Radio and Television Report to the American People on the Developments in Eastern Europe and the Middle East.”

Korean War: Documents “Report to the American People on Korea,” “Address to Congress”

McCarthyism: (see Domestic Anticommunism)

Militarization: “United States Objectives and Programs for National Security (NSC 68),” and “Farewell Address.”

National Security Council: “United States Objectives and Programs for National Security (NSC 68),” “NSC 5412/2, Covert Operations,” “Meeting on Cuba,” and “National Security Directive 23, ‘United States Relations with the Soviet Union.'”

Nuclear Weapons: “Sentencing of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg,” “A Policy of Boldness,” “Organized Evacuation of Civilian Populations in Civil Defense,” “Limited Test Ban Treaty,” and “Address to the Nation on Defense and National Security.”

Policymaking: “The Long Telegram,” “Special Message to the Congress on Greece and Turkey (The Truman Doctrine),” “European Initiative Essential to Economic Recovery (the Marshall Plan),” “Crisis in Asia–An Examination of U.S. Policy,” “United States Objectives and Programs for National Security (NSC 68),” “A Policy of Boldness,” “Organized Evacuation of Civilian Populations in Civil Defense,” “Address to the Nation on Defense and National Security,” and “National Security Directive 23, ‘United States Relations with the Soviet Union'”

Presidents:

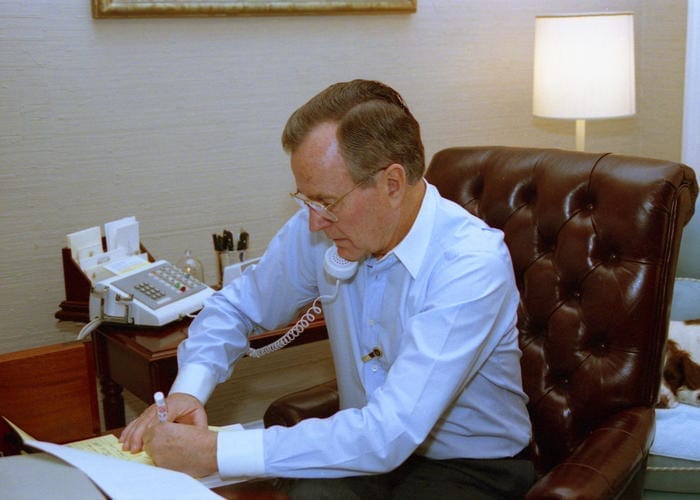

–Bush, George H.W.: “National Security Directive 23, ‘United States Relations with the Soviet Union'”, and “Telephone Conversation.”

–Carter, Jimmy: “Address at Commencement Exercises at the University of Notre Dame,” and “Address to the Nation on the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan,”

–Eisenhower, Dwight: “A Policy of Boldness,” “Radio and Television Report to the American People on the Developments in Eastern Europe and the Middle East,” “The Kitchen Debate,”and “Farewell Address.”

–Ford, Gerald: “Meeting on Cuba.”

–Johnson, Lyndon: “Special Message to the Congress on U.S. Policy in Southeast Asia”, “Joint Resolution of Congress”, “Peace Without Conquest”, “Compromise Solution for South Vietnam”

–Kennedy, John: “Inaugural Address”, “Report to President Kennedy on South Vietnam”, “Statement on Cuba”, “Minutes of the Meeting of the Special Group (Augmented) on Operation MONGOOSE”, “Soviet Reactions to Certain U.S. Courses of Action on Cuba”, “Radio and Television Report to the American People on the Soviet Arms Buildup in Cuba”, “Remarks in the Rudolph Wilde Platz”

–Nixon, Richard: “The Kitchen Debate”, “Address to the Nation Announcing Conclusion of an Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam”, “Telephone Conversation about Chile”, “Joint Statement Following Discussions with Leaders of the People’s Republic of China.”, “Address to the Nation Announcing Conclusion of an Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam”, “Telephone Conversation about Chile.”

–Reagan, Ronald: “Address to the Nation on Defense and National Security”, “Remarks on East-West Relations at the Brandenburg Gate in West Berlin”,

–Truman, Harry: “Special Message to the Congress on Greece and Turkey (The Truman Doctrine)”,, “Report to the American People on Korea”, “Farewell Address”

Propaganda: “The Negro in American Life (Guidance for the Voice of America)”, “The Kitchen Debate”

Red Scare: see Domestic Anticommunism

Social effects: “The Kitchen Debate”, “The Port Huron Statement”, “Statement by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee on the War in Vietnam”

Soviet Union: “The Long Telegram”, “United States Objectives and Programs for National Security (NSC 68)”, “Radio and Television Report to the American People on the Developments in Eastern Europe and the Middle East”, “The Kitchen Debate”, “Statement on Cuba”, “Soviet Reactions to Certain U.S. Courses of Action on Cuba”, “Radio and Television Report to the American People on the Soviet Arms Buildup in Cuba”, “Limited Test Ban Treaty”, “Address to the Nation on the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan,”, “Remarks on East-West Relations at the Brandenburg Gate in West Berlin”, “National Security Directive 23, ‘United States Relations with the Soviet Union'”

Vietnam War: “Report to President Kennedy on South Vietnam,”, “Special Message to the Congress on U.S. Policy in Southeast Asia”, “Joint Resolution of Congress”, “Peace Without Conquest”, “Compromise Solution for South Vietnam”, “Statement by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee on the War in Vietnam”, “Compromise Solution for South Vietnam”, “Joint Statement Following Discussions with Leaders of the People’s Republic of China.”, “Address to the Nation Announcing Conclusion of an Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam”

For each of the Documents in this collection, we suggest below in section A questions relevant for that document alone and in Section B questions that require comparison between documents.

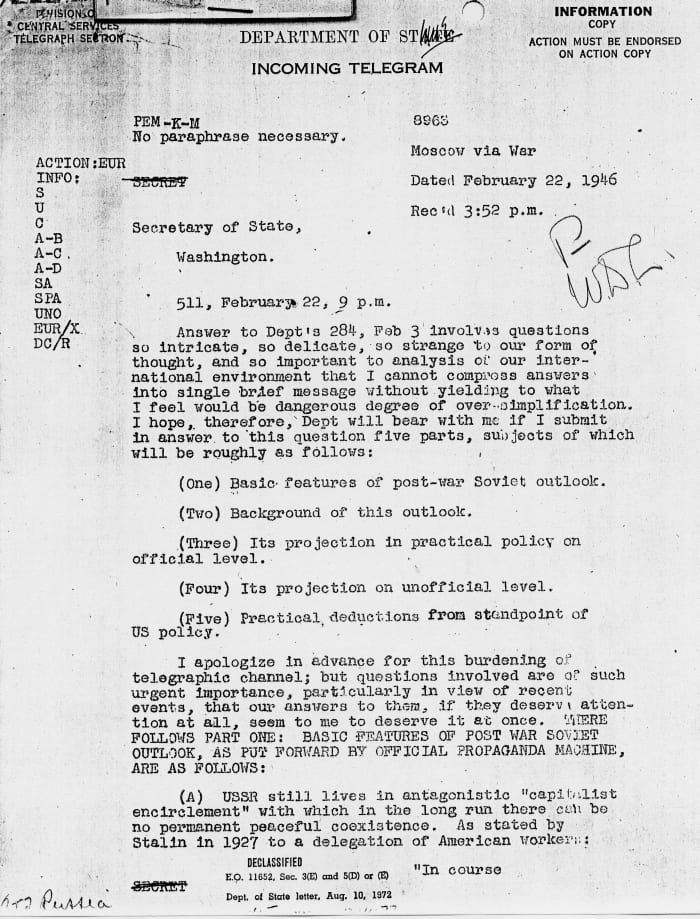

1. George Kennan, The Long Telegram, February 22, 1946

A. Why does Kennan believe the Soviet Union poses a threat to the United States? Why is the Soviet Union so suspicious of the outside world and how do these suspicions shape Soviet foreign policy? What actions are the Soviets likely to take and how should the United States respond? Does Kennan believe the United States should go to war against the Soviet Union?

B. How similar are the policies proposed by Kennan to those proposed in Truman and “United States Objectives and Programs for National Security?” How do Kennan, Truman and “United States Objectives and Programs for National Security” show the “containment” of communism becoming the centerpiece of U.S. foreign policy? In what ways does Lyndon Johnson use containment as a justification for U.S. action in South Vietnam in his “Special Message to the Congress on U.S. Policy in Southeast Asia” and “Peace Without Conquest“? How do Dulles and the Students for a Democratic Society criticize containment?

A. Why are Greece and Turkey important to the United States? What threats do the two nations face? What does Truman believe the United States should do to help Greece and Turkey? What are the two “alternative ways of life” almost all nations must now choose between, according to the president? Why should the United States help nations and people choose one of these alternatives? Why does the president refer to the costs of World War II in his address?

B. How does the policy recommended by Truman resemble the proposals put forward by George Kennan? How are they different? Is the Marshall Plan an extension of the Truman Doctrine? Does Truman believe that aid to Greece and Turkey was the correct action to take when he gives his Farewell Address? In what ways do Rusk and McNamara resemble the Truman Doctrine?

A. What problems continue to bother Europe’s economy? What are the required solutions? Why does Marshall believe it is “logical” for the United States to help fix these problems? If the United States doesn’t help, what might happen in Europe? Why does Marshall believe Europeans should take the initiative while the U.S. assists? What are the hoped-for outcomes?

B. How closely related are the Marshall Plan and the Truman Doctrine? Is the Marshall Plan a fulfillment of George Kennan’s recommendations? Is NSC 68 a break with the approach of the Marshall Plan?

4. Dean Acheson, “Crisis in Asia – An Examination of U.S. Policy,” January 12, 1950

A. Why does Acheson believe it is impossible to have a single “Asian policy”? What common factors should the United States consider in its policies in the Pacific and Far East? Why do the Chinese nationalists lose the war to the Chinese communists? Why is the Soviet Union (which Acheson also calls Russia) interested in north China? Why is Japan important to the United States? What is the “defensive perimeter” (that is, a line to defend) the United States should have in the Pacific and Far East? What does Acheson say nations on the other side of the perimeter should do if attacked?

B. In this speech, Acheson defends the Truman administration against criticisms that it is “soft” on communism in Asia – how do Senator Joseph McCarthy and General Douglas MacArthur step up these criticisms? Does Truman show Truman following the policies recommended by Acheson?

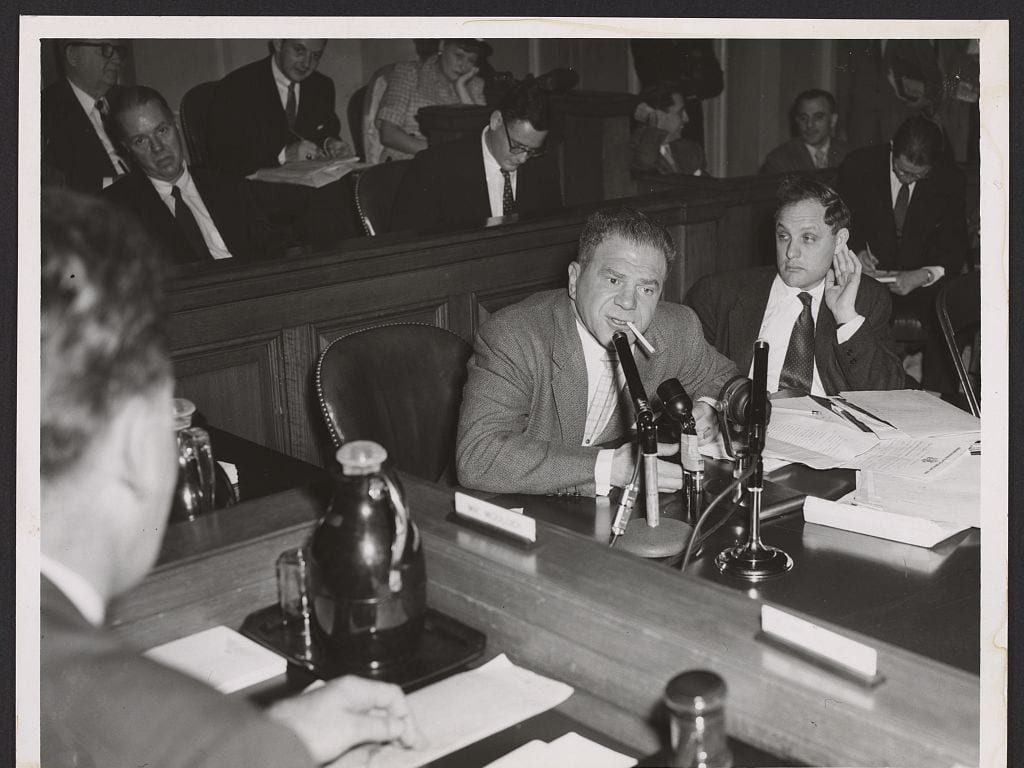

A. Why does McCarthy believe the United States is losing the Cold War? According to McCarthy, who within the United States is helping the communists? What kind of list does McCarthy claim to have? Why might his accusation have attracted lots of attention and controversy? What does he think must be done?

B. How does Robert Treuhaft question the fear and alarm raised by speeches like McCarthy’s? How is Smith a rejection of the approach taken by McCarthy? Does Smith agree with McCarthy on any points? How do the Students for a Democratic Society criticize

the widespread fear of communism?

A. What are the basic purposes of the United States? What are the basic purposes of the Soviet Union? What does NSC 68 predict will happen if the United States and its allies fail to act to stop the Soviet Union? What steps should the United States and its allies take? What advantages and strengths does the United States have?

B. How do the view of the Soviet Union and the threat of communism expressed in this document differ from the views expressed by Kennan and Truman? How might the outbreak of the Korean War (See Truman and MacArthur) have made NSC 68 appear more credible? How is Dulles similar to NSC 68?

7. Margaret Chase Smith, Declaration of Conscience, June 1, 1950

A. Why does Smith believe she needs to speak out? What are the “basic principles of Americanism”? What criticisms does Chase make of the Truman administration and the Democratic Party? Why is Chase also critical of her own party, the Republicans? What challenges does the Republican Party face? What is the Declaration of Conscience?

B. In what ways does this speech criticize the tone and content of McCarthy? How is the definition of Americanism in this document similar to the American Way defined in NSC 68? In what ways are this speech and Treuhaft’s similar?

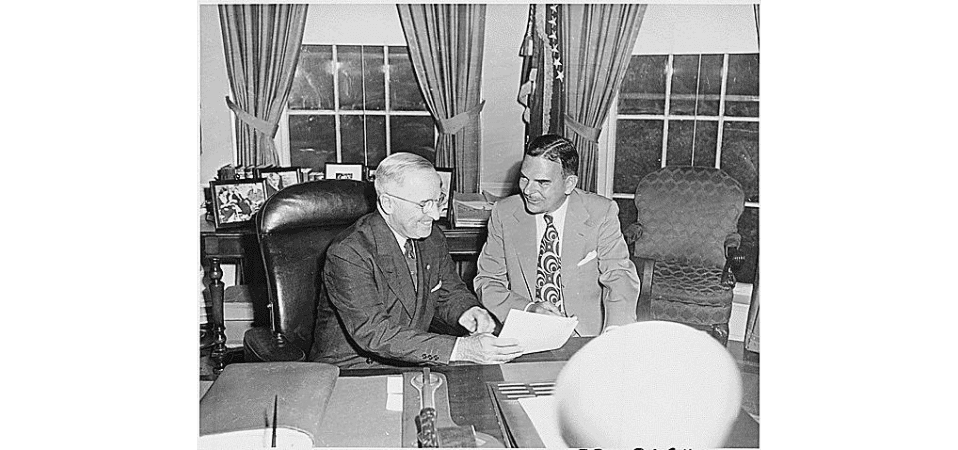

8. Harry S. Truman, Report to the American People on Korea, April 11, 1951

A. Why is the United States fighting in Korea? What have the United States and its allies accomplished so far? Why hasn’t the United States directly attacked China? What are the risks of expanding the war? Why does the president relieve General MacArthur of his duties in Korea?

B. How do Truman’s explanations of the purposes of fighting in Korea show the policy of containment (See Kennan, Truman, and Marshall) being applied? In what ways does this document show the influence of NSC 68? Does Truman appear to be responding to critics who accuse the administration of not doing enough to fight communism (See McCarthy and Smith)? Does Truman seem to expect General Douglas MacArthur will criticize him too?

9. General Douglas D. MacArthur, Address to Congress, April 19, 1951

A. What is at stake in the Korean War, according to MacArthur? What does he think must be done to win the war? Why is communist China such a great threat to the United States and the rest of the world? In what ways is MacArthur critical of the Truman administration’s conduct of the war? Does he praise the administration in any way?

B. In what ways is this speech a criticism of the policies outlined by Secretary of State Dean Acheson? Do MacArthur’s recommendations provide the “boldness” called for by John Foster Dulles? How is MacArthur’s view of communism similar to the view expressed in NSC 68?

10. Judge Irving Kaufman, Sentencing of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, April 5, 1951

A. Why does Kaufman believe the Rosenbergs are guilty of a crime worse than murder? What problems have resulted because of the help given to the Soviet Union? Do you think the couple’s death sentence is too harsh? Why or why not?

B. How do McCarthy and Smith make similar statements about the danger of espionage? Do Kaufman, McCarthy, and Smith exaggerate the threat of spies?

A. What themes or topics does the Voice of America (VOA) emphasize in its coverage of African Americans? How does the VOA handle the topic of civil rights? Why do you think the VOA carries lots of statements by African Americans who are critical of communism? How does the VOA handle news of attacks and violence against African Americans?

B. Does this guidance show an early effort to present the United States as a nation committed to protecting human rights in the ways described by Jimmy Carter? How might VOA features on African Americans have advanced the purposes of containment as expressed by Kennan, Truman, Marshall, and NSC 68?

12. John Foster Dulles, “A Policy of Boldness,” May 19, 1952

A. Why is Dulles so critical of containment? What does he propose as an alternative? What does he believe are the advantages of “boldness”? How can allies help the United States? Why does Dulles believe threatening to use nuclear weapons is a good policy? Does he admit any risks of such a policy?

B. How does the stalemate in the Korean War (See Truman and MacArthur) influence this article? Is the 1956 uprising in Hungary (See Eisenhower) an example of the liberation of people living under communist rule that the United States should attempt? Does the U.S. State Department show the Voice of America being used in the ways Dulles wants? Is Reagan also a call for liberation? If so, how?

A. What kind of evacuation does the policy propose? Who is responsible for carrying out the evacuation? Who do you think the “priority groups” for evacuation might be? Why doesn’t the policy provide details about how to evacuate?

B. Would this policy help make the “policy of boldness” more acceptable to Americans? Why or why not? How does the Port Huron Statement show fears about nuclear war?

14. Harry S. Truman, Farewell Address, January 15, 1953

A. What does Truman say about the Cold War? Which policies carried out during his presidency does he mention? Why do you think he chooses to bring them up? Why he is optimistic that the United States will triumph over communism? What is communism’s basic failing? What possible ways could the Cold War end?

B. How does this speech compare to President Eisenhower’s Farewell Address? What are the major similarities and differences? How do other presidents emphasize the cause of worldwide freedom in their speeches (See Kennedy, Kennedy, Johnson, Carter, and Reagan)?

A. Why does Treuhaft believe he has been called before the committee? Why is he having so much trouble finding an attorney to represent him? Why does he believe the committee’s actions are damaging to the Constitution and to the country? Is Treuhaft ignoring the threat communism poses to the nation?

B. Are Senator Joseph McCarthy’s speech and Judge Irving Kaufman’s sentencing statement examples of the “hysteria” Treuhaft believes is spreading across the country? Are committee hearings an effective way to uncover illegal communist activity? What are the similarities between Treuhaft’s testimony and Smith’s?

16. National Security Council Directive, NSC 5412/2, Covert Operations, December 28, 1955

A. Why does the National Security Council believe the United States should undertake covert (that is, secret) operations? What are such operations supposed to accomplish? What types of operations are planned? Why does the National Security Council believe the United States should hide or deny its sponsorship of these operations?

B. Are the plans and operations described in Operation MONGOOSE, Kissinger and Rogers, Nixon and Kissinger, and Washington Specially Actions Group Meeting on Cuba examples of the covert operations called for by the National Security Council? What are the potential positive and negative results of covert operations? Why does President Carter criticize the use of covert operations?

A. What happens in Eastern Europe after World War II? Why hasn’t the United States used force to liberate Eastern Europe? How is the United States now responding to the Hungarian uprising? What does the United States hope will happen?

B. Is the uprising in Hungary an example of how people could be freed from communism as called for by John Foster Dulles? If so, why do you think the United States doesn’t directly help the uprising?

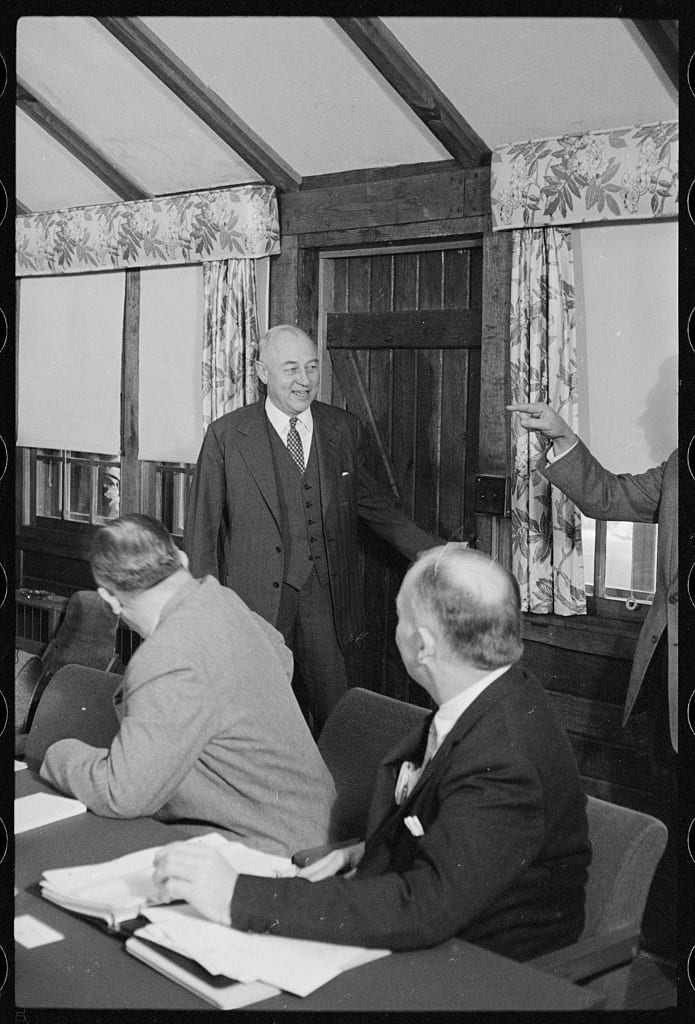

18. Richard Nixon and Nikita Khrushchev, The Kitchen Debate, July 25, 1959

A. How does Khrushchev hope the exhibit might improve relations between the United States and the Soviet Union? How does Nixon think Soviet visitors will respond to the exhibit? Why does Nixon believe communication, especially through television, is necessary for both nations? How is Khrushchev’s claim that American homes only last 20 years a criticism of capitalism? How does Nixon respond?

B. George Kennan says that the Russian people are eager to know more about the United States: how does the exhibit give them information about Americans? How might exhibits such as this one have supported other international outreach efforts by the United States (See Guidance for Voices of America)?

19. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Farewell Address, January 17, 1961

A. What is the basic purpose of the United States, according to Eisenhower? Why must the nation be careful to avoid big increases in defense spending? What does he mean by a “military-industrial complex”? Why is it a hazard to the nation? Why is so much federal support for corporate and university research also a danger?

B. In what ways does the Port Huron Statement echo Eisenhower’s concerns about defense spending? Compare Eisenhower’s speech to Reagan’s: had Eisenhower’s advice been followed by the time Ronald Reagan speaks on the topic of national security?

20. John F. Kennedy, Inaugural Address, January 20, 1961

A. What will the United States do to defend liberty? Why must the United States help end poverty around the world? What are the common “enemies of man”? What does President Kennedy ask Americans to do? What is his request of the people of the world? What does he believe global cooperation and friendship can accomplish? Is this speech a major reshaping of American Cold War goals and policies?

B. In what ways is Kennedy’s speech similar to Truman’s Special Message to Congress on Greece and Turkey, Truman’s Farewell Address , and Eisenhower’s Farewell Address? Are there differences – if so, what are they? In what ways does Johnson’s “Peace Without Conquest” also express optimism and confidence?

21. Dean Rusk and Robert McNamara, Report to President Kennedy on South Vietnam, November 11, 1961

A. Why must the United States take action to stop the spread of communism to South Vietnam? How will a failure to stop communism hurt the United States? What is the main U.S. objective in South Vietnam? What must the United States be willing to do to achieve this objective? How can other nations (especially those in SEATO) help?

B. In what ways does this report resemble the recommendations made by Truman and NSC 68? Does President Johnson carry out this report’s recommendations? Compare the report to Ball: why do these authors have such differing views on what the United States should do in Vietnam?

22. Students for a Democratic Society, the Port Huron Statement, 1962

A. Why are the students uncomfortable with the world as it is? What problems currently exist in the United States? What kind of new social system do they want to create? How are they critical of American Cold War policies and actions? Do the students see communism as a problem?

B. Compare the students’ view of the threat of communism with the views

expressed in one of the following documents: Kennan, Truman, NSC 68, Dulles, or Rusk and McNamara. How are the views different? Similar? Why might the students later be critical of the war in Vietnam? What might the students say about the way in which the Voice of

America covers civil rights (See Guidance for the Voice of America) – would they approve of this coverage? How are the warnings about militarization similar to the caution offered by President Eisenhower?

23. John F. Kennedy, Statement on Cuba, September 4, 1962

A. Why is the United States concerned about Soviet actions in Cuba? Why does Kennedy believe Soviet action must be considered part of a global challenge to the United States? What will the United States do next?

B. Compare this speech to Kennedy’s: how are they similar? How does this speech show the United States fulfilling the policy of containment called for in Kennan, Truman, and NSC 68?

24. Minutes of the Meeting of the Special Group (Augmented) on Operation MONGOOSE, October 4, 1962

A. Who do you think is the “higher authority” that wants more progress on Operation MONGOOSE? Why does the group want to use Cuban exiles to carry out sabotage against the Cuban government? What problems might “massive activity” cause for the United States? What actions does the group recommend?

B. Does this document carry out the goals of NSC 5412/2? Compare Operation MONGOOSE to Meeting on Cuba: how much do U.S. policies toward Cuba change between 1962 and 1976? Why do you think it is so important to the United States to get rid of communism in Cuba? What other documents in this collection might help answer this question?

A. Why is the Soviet Union putting missiles in Cuba? Why must the United States force the missiles’ removal? What are the advantages and disadvantages of the options (warning or blockade) to get the missiles out of Cuba? How might the Soviet Union respond to U.S. actions? How likely is the chance of an all-out war between the Soviet Union and the United States?

B. NSC 68 predicts the Soviet Union will try to dominate the world. Does the Central Intelligence Agency show this prediction coming true? Is the placement of missiles a response to the actions taken by the United States in Operation MONGOOSE?

A. What is the threat facing the United States, according to President Kennedy? Why can’t the United States and the world accept the placement of Soviet missiles in Cuba? What actions does Kennedy order? Does he fully explain the dangers of the situation?

B. Compare the Central Intelligence Agency and Kennedy. At the time, the Soviet Reactions are classified, meaning that they are not made public; Kennedy’s is a public speech. What are the similarities in how the two documents assess the placement of missiles in Cuba? What are the differences? In his speech, does Kennedy keep the promises he made in his Statement on Cuba? Does the Soviet Union’s placement of missiles in Cuba show the Soviet Union testing the resolve of the United States as George Kennan predicted?

27. John F. Kennedy, Remarks in the Rudolph Wilde Platz, Berlin, June 26, 1963

A. Why do you think President Kennedy came to Berlin to speak? What is the “great issue” between the free and communist worlds? How is Berlin part of this struggle? Why is it so important to protect Berlin?

B. Compare this speech to Eisenhower’s: how do both Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy try to boost the spirits of people living under (or close to) communism? Also compare Kennedy’s speech to his Inaugural Address and President Reagan’s Berlin speech. How similar are these three speeches? What are the major differences? What do both presidents say about the cause of freedom?

28. Limited Test Ban Treaty, August 5, 1963

A. What does the treaty ban? How effective is the treaty? Why might other nations sign this agreement? How might a test ban inspire disarmament initiatives?

B. Do you think the Cuban Missile Crisis (See Kennedy, Operation MONGOOSE, Central Intelligence Agency, and Kennedy) motivated the United States and the Soviet Union to draft this treaty? Is the treaty ban a fulfillment of the promise of disarmament Kennedy called for in his Inaugural Address?

29. Lyndon Johnson, Special Message to the Congress on U.S. Policy in Southeast Asia, August 5, 1964

A. Why does President Johnson want a Congressional resolution? What obligations does the United States have in Southeast Asia? What are the main features of U.S. policy? What must the United States do to carry out this policy? How can Congress help?

B. Does this speech show the president following the recommendations made by Rusk and McNamara? Compare Johnson and the Joint Resolution of Congress: does the Congressional resolution give the president what he asks for? In what ways does President Johnson further develop the rationale for U.S. military action in Vietnam?

30. Joint Resolution of Congress, H.J. RES 1145, August 7, 1964

A. What does the resolution give the president the power to do? Why is this authorization necessary? Does the resolution place any checks or limits on presidential action? What might be the advantages and disadvantages to having such limits?

B. Is the resolution similar to the Truman Doctrine and the Marshall Plan? In what ways? Are there differences?

31. Lyndon Johnson, “Peace Without Conquest,” April 7, 1965

A. Why is the United States in Vietnam? Why is President Johnson confident the United States will achieve its goals? What are these goals? Why does Johnson believe it would be disastrous for the United States to withdraw? Why does he work so hard to persuade Americans that the war in Southeast Asia must be fought?

B. Compare this speech his Special Message to Congress on U.S. Policy in Southeast Asia: how consistent are these statements about the importance of Vietnam and Southeast Asia? Does this speech echo the policies and principles President Truman offers? Compare this speech with Nixon: under President Nixon, does the United States still have the same goals in Vietnam as stated by President Johnson?

32. George Ball, A Compromise Solution for Vietnam, July 1, 1965

A. Why does Ball doubt that U.S. forces can defeat the communists? What question must the United States answer, and why must a decision be made now? What is the compromise solution?

B. Why do President Johnson and Ball come to such differing conclusions about the situation in Vietnam? Is Ball rejecting the guiding principle of the U.S. Cold War policy, that the United States must stop the spread of communism? Does Ball’s advice reflect George Kennan’s advice that the United States must choose carefully where and when it seeks to stop the spread of communism? Does the Statement on the War in Vietnam show that Ball is correct about the problem of using U.S. forces to fight in Vietnam?

33. Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Position Paper on Vietnam, January 6, 1966

A. Why does the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) oppose the war in Vietnam? What criticisms does SNCC make about the U.S. government? What does SNCC ask Americans to do?

B. Why might the SNCC paper have angered President Johnson? Are SNCC’s criticisms of the war similar to those of George Ball?

34. Richard Nixon, Address to the Nation on the War in Vietnam, November 3, 1969

A. Why does President Nixon not immediately end U.S. involvement in Vietnam’s war when he becomes president? According to the president, how and why did the United States become involved in Vietnam? What peace terms does he propose? Who is holding up an agreement? What is the Nixon Doctrine?

B. Compare this speech to Johnson’s Special Message to Congress and his “Peace Without Conquest“: does the United States still have the same goals in Vietnam in 1969 as it did in 1964 – 1965? Does the Nixon Doctrine show a change to the recommendations in NSC 68 regarding U.S. support for its allies? If so, how might the war in Vietnam have brought about this change? Compare Nixon’s 1973 speech to this speech: does the United States achieve its goals when the war ends?

35. Henry Kissinger and William Rogers, Telephone Conversation about Chile, September 14, 1970

A. Why do you think certain passages are blacked out before this document is made public? Why is the popularity of Salvador Allende so alarming? What is the United States considering doing in Chile?

B. Compare this document to NSC 5412/2, Operation MONGOOSE, and the Meeting on Cuba: how similar are the proposed actions? Why do you think covert or secret operations were appealing to U.S. policymakers? Do Nixon and Kissinger show the United States carrying out Kissinger’s and Rogers’s recommendations in Chile? How do secret operations against Cuba and Chile fulfill the U.S. commitment to stop the spread of communism? Why is President Carter critical of such operations?

A. Why does President Nixon make a trip to China? How do the leaders of both China and the United States find the visit beneficial? What does the United States state as its basic position on the international situation? What does China state as its position? How do these statements differ? What do both nations hope to accomplish by maintaining contact?

B. In what ways does his statement repeat basic U.S. Cold War policies as expressed by Kennan, Truman, Marshall, and NSC 68? Using Nixon, explain how the Joint Statement shows the influence of the Vietnam War on U.S.-Chinese relations. Using Truman’s report, explain how this statement shows the influence of the Korean War on U.S.-Chinese relations.

A. What are the terms of the peace agreement? Why does President Nixon say that the agreement is “only the first step” to peace? What does he promise the United States will continue to do in Vietnam? Why does he address “special words” to the North Vietnamese, South Vietnamese, and the American people? How do these messages differ?

B. Compare this to Rusk and McNamara, Johnson, and Nixon: Does the United States achieve its basic goals in Vietnam as stated in these earlier documents? How do you think Americans respond to the end of the war?

38. Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger, Telephone Conversation about Chile, September 16, 1973

A. Why are Henry Kissinger and President Nixon upset with the media? Why are both men pleased with what is happening in Chile? Why does President Nixon refer to communist Cuba and its leader Fidel Castro?

B. In what ways do Kissinger and Rogers reveal that the U.S. had been considering a move against Chile’s government for several years? Do Kissinger and Rogers in 1970 and in 1973 carry out the recommendations of NSC 5412/2? How does the action in Chile compare to efforts to undermine Cuba’s communist government? (See Operation MONGOOSE and the Meeting on Cuba). Why is President Carter critical of covert operations?

39. Washington Special Actions Group, Meeting on Cuba, March 24, 1976

A. Why is the United States considering military actions against Cuba? Why are these officials concerned about what is happening in Africa? What do they believe should be done and why?

B. Compare the Meeting on Cuba to Operation MONGOOSE: In what ways are the proposed actions against Cuba similar? How do they differ? At the end of the Meeting on Cuba, Henry Kissinger expresses a concern that the United States should not appear weak: what other documents that you have read show the same concern?

A. What are the fundamental values of the United States? How does President Carter believe they can guide U.S. foreign relations? Why is he critical of the Vietnam War? Why should the United States not fear a “new world”? What is this new world?

B. How is President Carter critical of previous approaches to stop the spread of communism? Does his criticism of the Soviet Union resemble other presidents’ concerns about that country? Why is he critical of the types of covert actions detailed in NSC 5412/2, Operation MONGOOSE, Kissinger and Rogers, and Nixon and Kissinger?

41. Jimmy Carter, Address to the Nation on the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan, January 4, 1980

A. Why is the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan a threat to the United States and the world? What must be done in response? What is the United States doing to force the Soviets to leave Afghanistan?

B. Compare the responses of the United States to the invasions of Korea and Afghanistan: what are the similarities and differences? How does the basic U.S. Cold War policy of containment influence both responses?

42. Ronald Reagan, Address to the Nation on the Defense and National Security, March 23, 1983

A. Why is it necessary for the United States to increase defense spending? Why is it also important to reduce the level of nuclear arms? How does President Reagan explain the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI)? Why do you think the Soviet Union viewed SDI as a threat?

B. Compare Reagan to Eisenhower: is SDI an example of the military-industrial complex and the scientific elite that President Eisenhower raised concerns about in 1961? Looking at Dulles, explain how Reagan shows changes in policies regarding nuclear weapons.

A. How does President Reagan explain the cause of freedom and use the Berlin Wall to point out the threat of communism? Why do you think the State Department doesn’t want him to call for the wall to be torn down? Why does President Reagan insist on saying this? Why is the statement so dramatic?

B. How is this speech similar to Kennedy’s? Why does President Reagan mention the Marshall Plan? How does he use the Marshall Plan to explain the success of democracy and capitalism?

A. What does the report say about the U.S. commitment to contain the spread of communism over the last 40 years? How is the policy successful? Why must the United States treat Soviet reforms with caution? What must the Soviets do to earn the trust of the United States? What should the United States do? Does the report suggest the end of the Cold War might be close?

B. Compare this document to the Long Telegram and NSC 68: how are these analyses of Soviet intentions and actions similar? Different? How much has the U.S. view of the Soviet Union changed since the late 1940s? Are the reforms taking place inside the Soviet Union the type of changes President Truman hoped for in his Farewell Address?

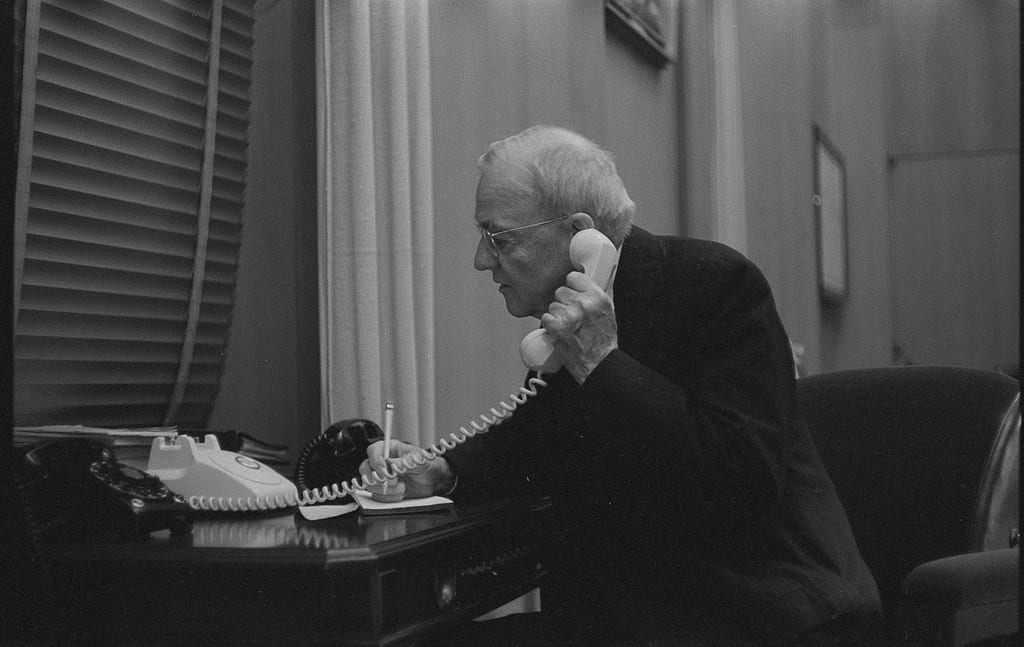

45. George H.W. Bush and Helmut Kohl, Telephone Conversation, November 10, 1989

A. Why do the Poles need U.S. and European help? What is the scene like at the Berlin Wall? What does Helmut Kohl ask the United States to do? Why does he thank President Bush? What does President Bush promise to do? Does this document show the Cold War coming to an end?

B. Compare this document to Truman’s: Do the events in Germany show President Truman’s predictions about the possible end of the Cold War coming true? If so, how? How does the fall of the Berlin Wall fulfill the goals of Presidents Kennedy and Reagan as expressed by Kennedy and and Reagan?

Belmonte, Laura A. Selling the American Way: U.S. Propaganda and the Cold War. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

Dudziak, Mary L. Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2000.

Engel, Jeffrey A., ed. The Fall of the Berlin Wall: The Revolutionary Legacy of 1989. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Fursenko, Aleksandr and Timothy Naftali. “One hell of a gamble”: Khrushchev, Castro, and Kennedy, 1958-1964. New York: Norton, 1997.

Gaddis, John Lewis. The Cold War: A New History. New York: Penguin Books, 2006.

Hajimu, Masuda. Cold War Crucible: The Korean Conflict and the Postwar World. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2015.

Haynes, John Earl, Harvey Klehr, and Alexander Vassiliev. Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2009.

Inboden, William. Religion and American Foreign Policy, 1945-1960: The Soul of Containment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Kaiser, David E. American Tragedy: Kennedy, Johnson, and the Origins of the Vietnam War. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2000.

Leffler, Melvyn. For the Soul of Mankind: The United States, the Soviet Union, and the Cold War. New York: Hill and Wang, 2007.

Leffler, Melvyn and Odd Arne Westad, eds. The Cambridge History of the Cold War. 3 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Mann, James. The Rebellion of Ronald Reagan: A History of the End of the Cold War. New York: Viking Press, 2009.

Offner, Arnold A. Another Such Victory: President Truman and the Cold War, 1945-1953. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2002.

Suri, Jeremi. Power and Protest: Global Revolution and the Rise of Détente. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2003.

Westad, Odd Arne. The Global Cold War: Third World Interventions and the Making of Our Times. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Whitfield, Stephen J. The Culture of the Cold War. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991.