Progressivism and the Presidential Election of 1912

This collection of primary source documents is intended to help readers identify and think about some of the key ideas and issues surrounding the U.S. Presidential election of 1912. The 1912 election was a significant event in American history for a number of reasons, representing the high-water mark of the so-called Progressive Era in American electoral politics. While we might simply associate this with Theodore Roosevelt’s short-lived Progressive Party, the election featured three major presidential candidates (and one significant minor candidate), represented by four separate parties, each of which professed to champion “progressive” politics in one fashion or another.

Exhibit Organization and Contents

The Election of 1912 exhibit consists of a scholarly explanation and analysis of the ideas that formed the basis of the candidates’ positions, the politics surrounding the three-way split of the electoral vote, and an assessment of the immediate fallout of the election. This analysis, by Dr. Jason Jividen, is supported by a selection of original documents. These documents are available as a list, and are mentioned within Dr. Jividen’s essay, below.

Table of Contents

- Election of 1912 Essay (below)

- Documents Selected for this Exhibit

- Electoral Map and Associated Data for 1912

The Progressive Era

The Progressive Era lasted from the early 1890’s to the early 1920’s, encompassing much more than the political party that backed Roosevelt in 1912. Progressivism was a broad intellectual and political movement that cut across political parties. In general, progressives sought to reinterpret the American political order by giving the people more direct power over all levels of government, and in turn, by giving a growing administrative state more power to regulate social and economic life. After the Civil War, the closing of the frontier was accompanied by increasing economic specialization, big business, large accumulations of wealth, and the rise of industrialization and urbanization. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, progressives argued that our political and economic circumstances had changed so fundamentally that individual equality of opportunity was increasingly threatened. In order for average Americans to achieve material satisfaction, many progressives claimed, government at all levels would need more power to address monopoly, to regulate key sectors of the economy, and to pursue various labor, banking, tariff, and currency reforms, among other proposals. Political corruption and so-called “special interests” compounded the problem, many argued, and some suggested that American institutions such as separation of powers, checks and balances, federalism, representation, and a cumbersome amendment process all frustrated progressive reform. Such features might warrant careful reevaluation and many progressives called for introducing more “direct” democratic mechanisms into American politics, including initiative and referendum, the direct election of senators, direct primary elections, the recall of elected officials and judges, and even the popular recall of judicial decisions. This is the political and economic landscape upon which the 1912 presidential election was conducted.

The Presidential Election of 1912

The Republican Party

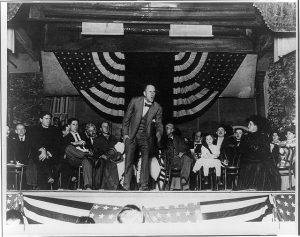

Held on November 5, the election featured three major presidential candidates, represented by three political parties: incumbent William Howard Taft (Republican Party), New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson (Democratic Party), and former President Theodore Roosevelt (Progressive Party). Perennial presidential candidate for the Socialist Party, Eugene V. Debs, rounded out the field as the most successful of a slate of minor candidates. The election is often studied by historians and political scientists due to the success of Roosevelt’s “Bull Moose” Progressive Party. The Republican Party had split into what some regarded as “progressive“ and “conservative” wings, with the latter being especially critical of the progressive embrace of a more direct democracy, tariff reform, and their willingness to challenge the constitutional authority of state and federal courts. In his famed 1910 “New Nationalism” Address at Osawatomie, Kansas, Roosevelt sought to reconcile these two wings in advance of the 1912 election. Although Taft had been Roosevelt’s hand-picked successor in the Republican Party, by 1912, the two had a personal and political falling out, with each arguing that the other had abandoned the principles of the party. Roosevelt accused Taft of embracing a de facto oligarchy, distrusting the people, and favoring the special interests of wealthy corporations. Taft accused Roosevelt of flirting with mob rule and engaging in a reckless disregard of constitutional norms, especially his support for the popular recall of controversial judicial decisions.

Challenging Taft for the presidential nomination, Roosevelt took advantage of the emerging prevalence of direct primaries across twelve states, carrying nine of them, securing a significant number of delegates over Taft and Wisconsin Senator Robert LaFollette, another Republican candidate for president. Ultimately, however, Roosevelt lost the party nomination to Taft at the 1912 Republican Party National Convention, (see Taft’s letter accepting the nomination) where state party leaders still controlled the nomination system. Incensed, Roosevelt formed the “Bull Moose” Progressive Party in order to challenge Taft. Continuing the theme he had begun in 1910, Roosevelt called his campaign the New Nationalism. In 1912, a very popular and charismatic former President Roosevelt made the most successful third party run for the presidency in American history, earning just over 27% percent of the national popular vote total and carrying six states with 88 electoral votes. The new party called for numerous reforms, including various forms of labor legislation, proposals for more direct democracy, lower tariff rates, income and inheritance taxes, women’s suffrage, and the regulation and breaking up of trusts. On the Progressive party’s program and Roosevelt’s critique of Taft and the Republicans, see the 1912 Progressive Party Platform, as well as Roosevelt’s “The Right of the People to Rule” and his speech accepting the 1912 Progressive nomination, “My Confession of Faith.”

Taft, for his part, garnered roughly 23% of the national popular vote, carrying just two states with eight electoral votes. Contemporary scholars sometimes follow Roosevelt’s lead in branding Taft as a “reactionary,” laissez faire conservative and a stumbling block to progressive reform. However, readers of primary sources, such as Taft’s letter accepting the Republican nomination, will see that the incumbent also claimed to pursue progressive politics, noting the party’s record on labor reform, pure food and drug legislation, trust-busting, and conservation, among other issues. (On the party’s program, also see the 1912 Republican Party Platform.) Careful observers will note that Taft’s brand of progressivism, if we may call it that, is an emphatically “constitutional” progressivism, that is, one that seeks progressive reform under the rubric of existing constitutional forms and political processes. Above all, Taft worried about a progressive politics that flatters short-term, passionate, and potentially tyrannical majority rule. This argument is especially clear in Taft’s speech “The Judiciary and Progress,” where he critiques Roosevelt’s proposals for the popular recall of judicial decisions.

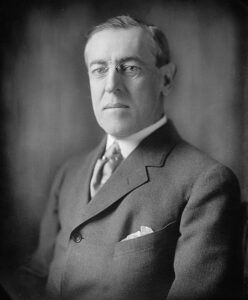

Democratic Party

Progressivism, again, cut across party boundaries in 1912, also characterizing the Democratic party. Political scientist and New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson was not lacking in progressive bona fides, yet he was forced to court the more traditional, Jeffersonian wing of the Democratic Party, and he only secured his party’s nomination after the 46th ballot of the convention. Wilson was a leading academic in progressive circles for many years and his scholarly work (especially on the presidency, the administrative state, and the principles of the American Founding) shows him to have been a chief architect of the American progressive movement. However, in his 1912 campaign rhetoric, Wilson sometimes pitched his New Freedom as a campaign in the service of Jeffersonian individualism and state’s rights, promising to restore economic competition by busting (rather than merely regulating) trusts, lowering tariffs, and reforming the banking system. These things, Wilson claimed, showed the daylight between his New Freedom and Roosevelt’s New Nationalism, the latter all too ready to compromise with select trusts in the form of regulation. (See the 1912 Democratic Party Platform and Wilson’s speech accepting the Democratic nomination.)

Wilson was, of course, elected President in 1912, gaining nearly 42% of the national popular vote total, carrying 40 states with 435 electoral votes. Some scholars suggest that, despite Wilson’s efforts to distinguish himself from Roosevelt, in practice the New Freedom was very much like the New Nationalism, with the creation of the Federal Reserve and the Federal Trade Commission, the Clayton Anti-Trust Act, and major national legislation on issues like child labor and the eight-hour work day.

Socialist Party

Finally, we should note the role that Indiana socialist Eugene Debs played as a minor presidential candidate in 1912. This was his fourth of five runs for the presidency, and the one in which he was most successful, gaining 6% of the national popular vote, but carrying no states and securing zero electoral votes. Other Socialist candidates had recently made inroads into the American political scene, with Milwaukee electing a Socialist mayor and a party member elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. For his part, Debs claimed that the major parties were in the pocket of wealthy businessmen, the trusts, and the banks, serving an oligarchy that oppressed average American workers. Debs used the platform to offer a full-throated defense of socialist political and economic policies, calling for—among other things—the nationalization of railroads and many other industries, various forms of labor legislation, women’s suffrage, initiative, referendum, and recall, and the abolition of the electoral college, the U.S Senate, and the presidential veto power. (See the 1912 Socialist Party Platform and Debs’ “Political Appeal to American Workers.”)