The Madison-Jefferson Exchange on Ratification and the Bill of Rights - Part I

James Madison and Thomas Jefferson engaged in an exchange by mail for over two years in which they discussed the debate over what would become the Bill of Rights. This long discussion took place during three distinct periods of time: 1) during the Federalist-Antifederalist “out of doors” debates; 2) after the ratification of the Constitution but before the meeting of the First Congress; and 3) during the debate over what rights Congress would submit to the states for adoption.

Since the exchange took place in three distinct topical and chronological phases, we have decided to embed these letters alongside other documents and commentary that describe these three periods of time.

The Madison-Jefferson Exchange, Part II (August 1788 – March 1789)

The Madison-Jefferson Exchange, Part III (March 1789 – February 1790)

Madison to Jefferson

December 9, 1787

The Constitution proposed by the late Convention engrosses almost the whole political attention of America. All the Legislatures except that of R. Island, which have been assembled, have agreed in submitting it to the State Conventions. Virginia has set the example of opening a door for amendments, if the Convention there should choose to propose them. Maryland has copied it. The States which preceded, referred the Constitution as recommended by the General Convention, to be ratified or rejected as it stands….

We have no certain information from the three Southern States concerning the temper relative to the New Government. It is in general favorable according to the vague accounts we have. Opposition however will be made in each….

Jefferson to Madison

PARIS, December 20, 1787

The season admitting only of operations in the Cabinet, and these being in great measure secret, I have little to fill a letter. I will therefore make up the deficiency by adding a few words on the Constitution proposed by our Convention. I like much the general idea of framing a government which should go on itself peaceably, without needing continual recurrence to the state legislatures. I like the organization of the government into Legislative, Judiciary and Executive. I like the power given the Legislature to levy taxes and for that reason solely approve of the greater house being chosen by the people directly. For though I think a house chosen by them will be very ill qualified to legislate for the Union, for foreign nations, etc. yet this evil does not weigh against the good of preserving inviolate the fundamental principle that the people are not to be taxed but by representatives chosen immediately by themselves. I am captivated by the compromise of the opposite claims of the great and little states, of the latter to equal, and the former to proportional influence. I am much pleased too with the substitution of the method of voting by persons, instead of that voting by states: and I like the negative given to the Executive with a third of either house, though I should have liked it better had the Judiciary been associated for that purpose, or invested with a similar and separate power. There are other good things of less moment.

I will now add what I do not like.

First the omission of a bill of rights providing clearly and without the aid of sophisms for freedom of religion, freedom of the press, protection against standing armies, restriction against monopolies, the eternal and unremitting force of the habeas corpus law, and trials by jury in all matter of fact triable by the laws of the land and not by the law of Nations. To say, as Mr. Wilson does that a bill of rights was not necessary because all is reserved in the case of the general government which is not given, while in the particular ones all is given which is not reserved might do for the Audience to whom it was addressed, but is surely gratis dictum, opposed by strong inferences from the body of the instrument, as well as from the omission of the clause of our present confederation which had declared that in express terms. It was a hard conclusion to say because there has been no uniformity among the states as to the cases triable by jury, because some have been so incautious as to abandon this mode of trial, therefore the more prudent states shall be reduced to the same level of calamity. It would have been much more just and wise to have concluded the other way that as most of the states had judiciously preserved this palladium, those who had wandered should be brought back to it, and to have established general right instead of general wrong. Let me add that a bull of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth, general or particular, and what no just government should refuse, or rest on inference.

The second feature I dislike, and greatly dislike, is the abandonment in every instance of the necessity of rotation in office, and most particularly in the case of the President. Experience concurs with reason in concluding that the first magistrate will always be re-elected if the constitution permits it. He is then an officer for life. This once observed it becomes of so much consequence to certain nations to have a friend or a foe at the head of our affairs that they will interfere with money and with arms. A Gallo man or an Anglo man will be supported by the nation he befriends. If once elected, and at a second of third election outvoted by one or two votes, he will pretend false votes, foul play, hold possession of the reins of government, be supported by the states for voting for him, especially if they are the central ones lying in a compact body themselves and separating their opponents; and they will be aided by one nation of Europe than ever the election of a king of Poland was. Reflect on all the instances in history ancient and modern, of elective monarchies, and say if they do not give foundation for my fears, the Roman emperors, the popes, while they were of any importance, the German emperors till they became hereditary in practice, the kings of Poland, the Days of the Ottoman dependencies. It may be said that if elections are to be attended with these disorders, the seldomer they are renewed the better. But experience shows that the only way to prevent disorder is to render them uninteresting by frequent changes. An incapacity to be elected a second time would have been the only effectual preventative. The power of removing him every fourth year by the vote of the people is a power which will not be exercised. The kind of Poland is removable every day by the Diet, yet he is never removed.

Smaller objections are the Appeal in fact as well as law, and the binding all persons Legislative, Executive and Judiciary by oath to maintain that constitution. I do not pretend to decide what would be the best method of procuring the establishment of the manifold good things in this constitution, and of getting rid of the bad. Whether by adopting it in hopes of future amendment, or, after it has been duly weighted and canvassed by the people, after seeing the parts they generally dislike, and those they generally approve, to say to them ‘We see now what you wish. Send together your deputies again, let them frame a constitution for you omitting what you have condemned, and establishing the powers you approve. Even these will be a great addition to the energy of your government.’

At all events I hope you will not be discouraged from other trials, if the present one should fail of it’s full effect.

I have thus told you freely what I like and dislike: merely as a matter of curiosity for I know your own judgment has been formed on all these points after having heard every thing which could be urged on them. I own I am not a friend to a very energetic government. It is always oppressive. The late rebellion in has given me more alarm than I think it should have done. Calculate that one rebellion in 13 states in the course of 11 years is but one for each state in a century and a half. No country should be so long without one. Nor will any degree of power in the hands of government prevent insurrections. France with all it’s despotism, and two or three hundred thousand men always in arms has had three insurrections in the three years I have been here in every one of which greater numbers were engaged than in Massachusetts and a great deal more blood was split….

After all, it is my principle that the will of the Majority should always prevail. If they approve the proposed Convention in all it’s parts, I shall concur in it cheerfully, in hopes that they will amend it whenever they shall find it work wrong. I think our governments will remain virtuous for many centuries; as long as they are chiefly agricultural; and this will be as long as there shall be vacant lands in any part of America.… Above all things I hope the education of the common people will be attended to; convinced that on their good sense we may rely with the most security for the preservation of a due degree of liberty. I have tired you by this time with my disquisitions and will therefore only add assurances of the sincerity of those sentiments of esteem and attachment with which I am Dear Sir your affectionate friend and servant,

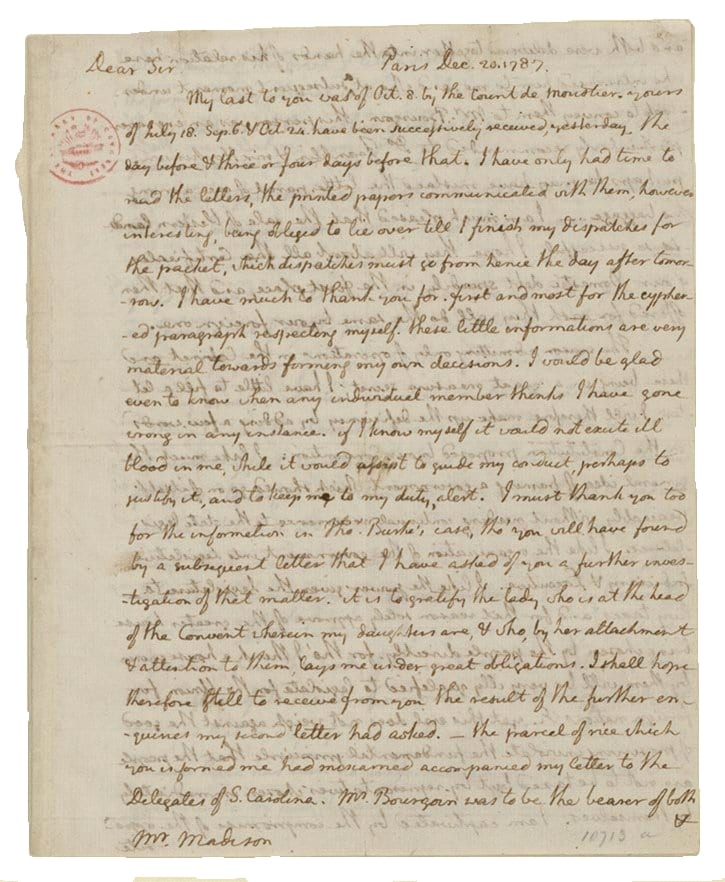

Jefferson to Madison

February 6, 1788

I am glad to hear that the new constitution is received with favor. I sincerely wish that the 9 first conventions may receive, and the last 4 reject it. The former will secure it finally, while the latter will oblige them to offer a declaration of rights in order to complete the union. We shall thus have all that’s good, and cure it’s principal defect.

Madison to Jefferson

February 19, 1788

The public here continues to be much agitated by the proposed federal Constitution and to be attentive to little else. At the date of my last Delaware Pennsylvania and New Jersey had adopted it. It has been since adopted by Connecticut, Georgia, and Massachusetts. In the first the minority consisted of 40 against 127. In Georgia the adoption was unanimous. In Massachusetts the conflict was tedious and the event extremely doubtful. On the final question the vote stood 187 against 168; a majority of 19 only being in favor of the Constitution.… The amendments as recommended by the Convention were as I am well informed not so much calculated for the minority in the Convention, on whom they had little effect, as for the people of the State. You will find the amendments in the Newspapers which are sent from the office of foreign affairs.… The minority of Connecticut behaved with equal moderation. That of Pennsylvania has been extremely intemperate and continues to use a very bold and menacing language.

Had the decision in Massachusetts been adverse to the Constitution, it is not improbable that some very violent measures would have followed in that State. The cause of the inflammation however is much more in their State factions, than in the system proposed by the Convention. New Hampshire is now deliberating on the Constitution. It is generally understood that an adoption is a matter of certainty, South Carolina and Maryland have fixed on April or May for their Conventions. The former it is currently said will be one of the ratifying States. Mr. Chase and a few others will raise a considerable opposition in the latter. But the weight of personal influence is on the side of the Constitution, and the present expectation is that the opposition will be outnumbered by a great majority. This State is much divided in its sentiment. Its Convention is to be held in June. The decisions of Massachusetts. will give the turn in favor of the Constitution unless an idea should prevail or the fact should appear, that the voice of the State is opposed to the result of its Convention.

North Carolina has put off her Convention till July. The State is much divided it is said. The temper of Virginia, as far as I can learn, has undergone but little change of late. At first there was an enthusiasm for the Constitution. The tide next took a sudden and strong turn in the opposite direction. The influence and exertions of Mr. Henry, and Col. Mason and some others will account for this. Subsequent information again represented the Constitution as regaining in some degree its lost ground. The people at large have been uniformly said to be more friendly to the Constitution than the Assembly. But it is probable that the dispersion of the latter will have a considerable influence on the opinions of the former. The previous adoption of nine States must have a very persuasive effect on the minds of the opposition, though I am told that a very bold language is held by Mr. H[enr]y and some of his partisans. Great stress is laid on the self-sufficiency of that State, and the prospect of external props are alluded to.

Madison to Jefferson

ORANGE, April 22, 1788

The proposed Constitution still engrosses the public attention. The elections for the Convention here are but just over and promulgated. From the returns (excluding those from Kentucky which are not yet known) it seems probable, thought not absolutely certain that a majority of the members elect are friends to the Constitution. The superiority of abilities at least seems to lie on that side.…

The adversaries take very different grounds of opposition. Some are opposed to the substance of the plan; others to particular modifications only. Mr. H[enr]y is supposed to aim at disunion. Col. M[aso]n is growing every day more bitter, and outrageous in his efforts to carry his point; and will probably in the end be thrown by the violence of his passions into the politics of Mr. H[enr]y. The preliminary question will be whether previous alterations shall be insisted on or not? Should this be carried in the affirmative, either a conditional ratification, or a proposal for a new Convention will ensure. In either event, I think the Constitution and the Union will both be endangered. It is not to be expected that the States which have ratified will reconsider their determinations, and submit to the alterations prescribed by Virginia. and if a second Convention should be formed, it is as little to be expected that the same spirit of compromise will prevail in it as produced by an amicable result to the first. It will be easy also for those who have latent views of disunion, to carry them on under the mast of contending for alterations popular in some but inadmissible in other parts of the U. States.

The real sense of the people of this States cannot easily be ascertained. They are certainly attached and with warmth to a continuance of the Union; and I believe a large majority of the most intelligent and independent are equally so to the plan under consideration. On a geographical view of them, almost all the counties in the N. Neck have elected federal deputies. The Counties on the South side of James River have pretty generally elected adversaries to the Constitution. The intermediate district is much chequered in this respect. The Counties between the blue ridge and the Alleghany have chosen friends to the Constitution without a single exception. Those Westward of the latter, have as I am informed, generally though not universally pursued the same rule. Kentucky is supposed will be divided.

Madison to Jefferson

April 27, 1788

Your remarks on the tax on transfers of land in a general view appear to me to be just but there were two circumstances which gave a peculiarity to the case in which our Law adopted it. One was that the tax will fall much on those who are evading their quotas of other taxes by removing Georgia and Kentucky.

Jefferson to Madison

May 3, 1788

Equal provision for the interest, adding to it a certain prospect for the principal, will give us a preference to all nations, the English not excepted. The first act of the new government should be some operation whereby they may assume to themselves this station.

The new government should by no means be left by the old to the necessity of borrowing a stiver before it can tax for it’s interest. This will be to destroy the credit of the new government in its birth.

Madison to Jefferson

NEW YORK, July 24 and 26, 1788

I returned here about ten days ago from Richmond which I left a day or two after the dissolution of the Convention. The final question on the new plan of Government was put on the 25th. of June. It was twofold 1. whether previous amendments should be made a condition of ratification. 2. directly on the Constitution in the form it bore. On the first the decision was in the negative, 88 being no, 80 only ay. On the second and definitive question, the ratification was affirmed by 89 ays against 79. noes. A number of alterations were then recommended to be considered in the mode pointed out in the Constitution itself. The meeting was remarkably full; Two members only being absent and those known to be on the opposite sides of the question. The debates also were conducted on the whole with very laudable moderation and decorum, and continued until both sides declared themselves ready for the question. And it may be safely concluded that no irregular opposition to the System will follow in that State, at least with the countenance of the leaders on that side. What local eruptions may be occasioned by ill-timed or rigorous executions of the Treaty of peace against British debtors, I will not pretend to say.

But although the leaders, particularly H[enr]y and M[a]s[o]n, will give no countenance to popular violences it is not to be inferred that they are reconciled to the event, or will give it a positive support. On the contrary both of them declared they could not go that length, and an attempt was made under their auspices to induce the minority to sign an address to the people which if it had not been defeated by the general moderation of the party, would probably have done mischief.

Among a variety of expedients employed by the opponents to gain proselytes, Mr. Henry first and after him Col. Mason introduced the opinions, expressed in a letter from a correspondent [Mr. Donald or Skipwith I believe] and endeavored to turn the influence of your name even against parts, of which I know you approved. In this situation I thought it due to truth as well as that it would be most agreeable to yourself and accordingly took the liberty to state some of your opinions on the favorable side. I am informed that copies or extracts of a letter from you were handed about at the Maryland Convention with a like view of impeding the ratification.

N. Hampshire ratified the Constitution on the 21st. Ult: and made the ninth State. The votes stood 57 for and 46. against the measure. S. Carolina had previously ratified by a very great majority. The Convention of N. Carolina is now sitting. At one moment the sense of that State was considered as strongly opposed to the system. It is now said that the tide has been for some time turning, which with the example of other States and particularly of Virginia prognosticates a ratification there also. The Convention of N. York has been in Session ever since the 17th. Ult: without having yet arrived at any final vote. Two thirds of the members assembled with a determination to reject the Constitution, and are still opposed to it in their hearts. The local situation of N. York, the number of ratifying States and the hope of retaining the federal Government in this City afford however powerful arguments to such men as Jay, Hamilton, and the Chancellor Duane and several others; and it is not improbable that some form of ratification will yet be devised by which the dislike of the opposition may be gratified, and the State notwithstanding made a member of the new Union.”

July 26.

We just hear that the Convention of this State have determined by a small majority to exclude from ratification everything involving a condition and to content themselves with recommending the alterations wished for.

Jefferson to Madison

PARIS, July 31, 1788

I sincerely rejoice at the acceptance of our new constitution by nine States. It is a good canvas, on which some strokes only want retouching. What these are, I think are sufficiently manifested by the general voice from north to south, which calls for a bill of rights. It seems pretty generally understood, that this should go to juries, habeas corpus, standing armies, printing, religion and monopolies. I conceive there may be difficulty in finding general modifications of these, suited to the habits of all the States.

But if such cannot be found, then it is better to establish trials by jury, the right of habeas corpus, freedom of the press and freedom of religion, in all cases, and to abolish standing armies in time of peace, and monopolies in all cases, than not to do it in any. The few cases wherein these things may do evil, cannot be weighed against the multitude wherein the want of them will do evil. In disputes between a foreigner and a native, a trial by jury may be improper. But if this exception cannot be agreed to, the remedy will be to model the jury by giving the mediatas linguae, in civil as well as criminal cases. Why suspend the habeas corpus in insurrections and rebellions? The parties who may be arrested, may be charged instantly with a well defined crime; of course, the judge will remand them. If the public safety requires that the government should have a man imprisoned on less probable testimony, in those than in other emergencies, let him be taken and tried, retaken and retried, while the necessity continues, only giving him redress against the government, for damages.

Examine the history of England. See how few of the cases of the suspension of the habeas corpus law, have been worthy of that suspension. They have been either real treasons wherein the parties might as well have been charged at once, or sham plots, where it was shameful they should ever have been suspected. Yet for the few cases wherein the suspension of the habeas corpus has done real good, that operation is now become habitual, and the minds of the nation almost prepared to live under its constant suspension.

A declaration, that the federal government will never restrain the presses from printing any thing they please, will not take away the liability of the printers for false facts printed. The declaration, that religious faith shall be unpunished, does not give impunity to criminal acts, dictated by religious error. The saying there shall be no monopolies, lessens the incitements to ingenuity, which is spurred on by the hope of a monopoly for a limited time, as of fourteen years; but the benefit even of limited monopolies is too doubtful, to be opposed to that of their general suppression. If no check can be found to keep the number of standing troops within safe bounds, while they are tolerated as far as necessary, abandon them altogether, discipline well the militia, and guard the magazines with them. More than magazine guards will be useless, if few, and dangerous, if many. No European nation can ever send against us such a regular army as we need fear, and it is hard if our militia are not equal to those of Canada or Florida. My idea then, is, that though proper exceptions to these general rules are desirable and probably practicable, yet if the exceptions cannot be agreed on, the establishment of the rules, in all cases, will do ill in very few. I hope, therefore, a bill of rights will be formed to guard the people against the federal government, as they are already guarded against their State governments, in most instances.

The abandoning the principle of necessary rotation in the Senate, has I see been disapproved by many; in the case of the President, by none. I readily therefore suppose my opinion is wrong, when opposed by the majority as in the former instance, and the totality as in the latter. In this however I should have done it with more complete satisfaction, had we all judged from the same position.)