The Madison-Jefferson Exchange on Ratification and the Bill of Rights - Part II

James Madison and Thomas Jefferson engaged in an exchange by mail for over two years in which they discussed the debate over what would become the Bill of Rights. This long discussion took place during three distinct periods of time: 1) during the Federalist-Antifederalist “out of doors” debates; 2) after the ratification of the Constitution but before the meeting of the First Congress; and 3) during the debate over what rights Congress would submit to the states for adoption.

Since the exchange took place in three distinct topical and chronological phases, we have decided to embed these letters alongside other documents and commentary that describe these three periods of time.

The Madison-Jefferson Exchange, Part I (October 1787 – July 1788)

The Madison-Jefferson Exchange, Part III (March 1789 – February 1790)

Madison to Jefferson

August 10, 1788

Madison informs Jefferson that New York has ratified the Constitution and that another “General Convention” would “terminate in discord.”

My last went off just as a vote was taken in the Convention of this State which foretold the ratification of the new Government. The later act soon followed and is enclosed. The form of it is remarkable. I enclose also a circular address to the other States on the subject of amendments, from which mischiefs are apprehended. The great danger in the present crisis is that if another Convention should be soon assembled, it would terminate in discord, or in alterations of the federal system which would throw back essential powers into the State Legislatures. The delay of a few years will assuage the jealousies which have been artificially created by designing men and will at the same time point out the faults which really call for amendment. At present the public mind is neither sufficiently cool nor sufficiently informed for so delicate an operation…

Congress have been employed for several weeks on the arrangements of times and places for bringing the new Government into agency. The first have been agreed on though not definitively, and make it pretty certain that the first meeting will be held in the third week in March. The place has been a subject of much discussion: and continues to be uncertain. Philadelphia as least eccentric of any place capable of affording due accommodations and a respectable outset to the Government was the first proposed. The affirmative votes were N. Hampshire, Connecticut, Pena. Maryd. Virga. and N. Carolina. Delaware was present and in favor of that place, but one of its delegates wishing to have a question on Wilmington previous to a final determination, divided that State and negatived the motion. N. York came next in view, to which was opposed first Lancaster which failed and then Baltimore which to the surprise of every body was carried by seven States, S. Carolina which had preferred N. York to the two other more Southern positions, unexpectedly concurring in this. The vote however was soon rescinded, the State of S. Carolina receding from, the Eastern States remonstrating against, and few seriously arguing the eligibility of Baltimore. At present the question lies as it was originally supposed to do between N. York and Phila. and nothing can be more uncertain than the event of it. Rhode Island which alone was disposed to give the casting vote to N. York has refused to give any final vote for arranging and carrying into effect a system to which that State is opposed, and both the Delegates have returned home.

Enclosure — The Circular Letter, from the Ratification Convention of the State of New York to the governors of the several states in the Union (July 28, 1788)

Sir:

We, the members of the Convention of this state, have deliberately and maturely considered the Constitution proposed for the United States. Several articles in it appear so exceptionable to a majority of us, that nothing but the fullest confidence of obtaining a revision of them by a general convention, and an invincible reluctance to separating from our sister states, could have prevailed upon a sufficient number to ratify it, without stipulating for previous amendments. We all unite in opinion, that such a revision will be necessary to recommend it to the approbation and support of a numerous body of our constituents.

We observe that amendments have been proposed, and are anxiously desired, by several of the states, as well as by this; and we think it of great importance that effectual measures be immediately taken for calling a convention, to meet at a period not far remote; for we are convinced that the apprehensions and discontents, which those articles occasion, cannot be removed or allayed, unless an act to provide for it be among the first that shall be passed by the new Congress.

As it is essential that an application for the purpose should be made to them by two thirds of the states, we earnestly exhort and request the legislature of your state to take the earliest opportunity of making it. We are persuaded that a similar one will be made by our legislature, at their next session; and we ardently wish and desire that the other states may concur in adopting and promoting the measure.

It cannot be necessary to observe, that no government, however constructed, can operate well, unless it possesses the confidence and good-will of the body of the people; and as we desire nothing more than that the amendments proposed by this or other states be submitted to the consideration and decision of a general convention, we flatter ourselves that motives of mutual affection and conciliation will conspire with the obvious dictates of sound policy to induce even such of the states as may be content with every article in the Constitution to gratify the reasonable desires of that numerous class of American citizens who are anxious to obtain amendments of some of them.

Our amendments will manifest that none of them originated in local views, as they are such as, if acceded to, must equally affect every state in the Union. Our attachment to our sister states, and the confidence we repose in them, cannot be more forcibly demonstrated than by acceding to a government which many of us think very imperfect, and devolving the power of determining whether that government shall be rendered perpetual in its present form, or altered agreeably to our wishes, and a minority of the states with whom we unite.

Madison to Jefferson

August 23, 1788

According to Madison, the New York Circular letter “has gained fresh hopes and extertions to those who opposed the Constitution.”

By that opportunity I enclosed copies of the proceedings of this State on the subject of the Constitution. North Carolina was then in Convention, and it was generally expected would in some form or other have fallen into the general stream. The event has disappointed us. It appears that a large majority has decided against the Constitution as it stands, and according to the information here received has made the alterations proposed by Virginia the conditions on which alone that State will united with others. Whether this be the precise state of the case I cannot say. It seems at least certain that she has either rejected the Constitution, or annexed conditions precedent to her ratification. It cannot be doubted that this bold step is to be ascribed in part to the influence of the minority in Virginia which lies mostly in the Southern part of the State, and to the management of its leader. It is in part ascribed also by some to assurances transmitted from leading individuals here, that New York would set the example of rejection. The event, whatever may be been its cause, with the tendency of the circular letter from the Convention of N. York, has somewhat changed the aspects of things and has given fresh hopes and exertions to those who opposed the Constitution. The object with them will be to effect an early Convention composed of men who will essentially mutilate the system, particularly in the article of taxation, without which in my opinion the system cannot answer the purpose for which it was intended. An early Convention is in every view to be dreaded in the present temper of America. A very short period of delay would produce the double advantage of diminishing the heat and increasing the light of all parties. A trial for one year will probably suggest more real amendments than all the antecedent speculations of our most sagacious politicians.

Madison to Jefferson

September 21, 1788

Madison explains the implications over the location of the capital.

The Circular letter from the New York Convention has rekindled an ardor among the opponents of the federal Constitution for an immediate revision of it by another General Convention. You will find it one of the papers enclosed the result of the consultations in Pennsylvania on that subject. Mr. Henry and his friends in Virginia enter with great zeal into the scheme. Governor Randolph also spouses it; but with a wish to prevent if possible danger to the article which extends the power of the Government to internal as well as external taxation. It is observable that the views of the Pennsylvania. meeting do not rhyme very well with those of the Southern advocates for a Convention; the objects most eagerly pursued by the latter being unnoticed in the Harrisburg proceedings. The effect of the Circular letter on the other States is less known. I conclude that it will be the same everywhere among those who opposed the Constitution, or contended for a conditional ratification of it. Whether an early Convention will be the result of this united effort is more than can at this moment be foretold. The measure will certainly be industriously opposed in some parts of the Union, not only by those who wish for no alterations, but by others who would prefer the other mode provided in the Constitution, as most expedient at present for introducing those supplemental safeguards to liberty against which no objections can be raised; and who would moreover approve of a Convention for amending the frame of the Government itself, as soon as time shall have somewhat corrected the feverish state of the public mind and trial have pointed its attention to the true defects of the system.

You will also find by one of the papers enclosed that the arrangements have been completed for bringing the new Government into action. The dispute concerning the place of its meeting was the principal cause of delay, the Eastern States with N. Jersey and S. Carolina being attached N. York, and the others strenuous for a more central position. Philadelphia, Wilmington, Lancaster and Baltimore were successively tendered without effect by the latter, before they finally yielded to the superiority of members in favor of this City. I am afraid the decision will give a great handle to the Southern Antifederalists who have inculcated a jealousy of this end of the Continent. It is to be regretted also as entailing this pernicious question on the new Congress who will have enough to do in adjusting the other delicate matters submitted to them. Another consideration of great weight with me is that the temporary residence here will probably end in a permanent one at Trenton, or at the farthest on the Susquehanna. A removal in the first instance beyond the Delaware would have removed the alternative to the Susquehanna and the Potomac. The best chance of the latter depends on a delay of the permanent establishment for a few years, until the Western and South Western population comes more into view. This delay cannot take place if so eccentric a place as N. York is to be the intermediate seat of business.

Madison to Jefferson

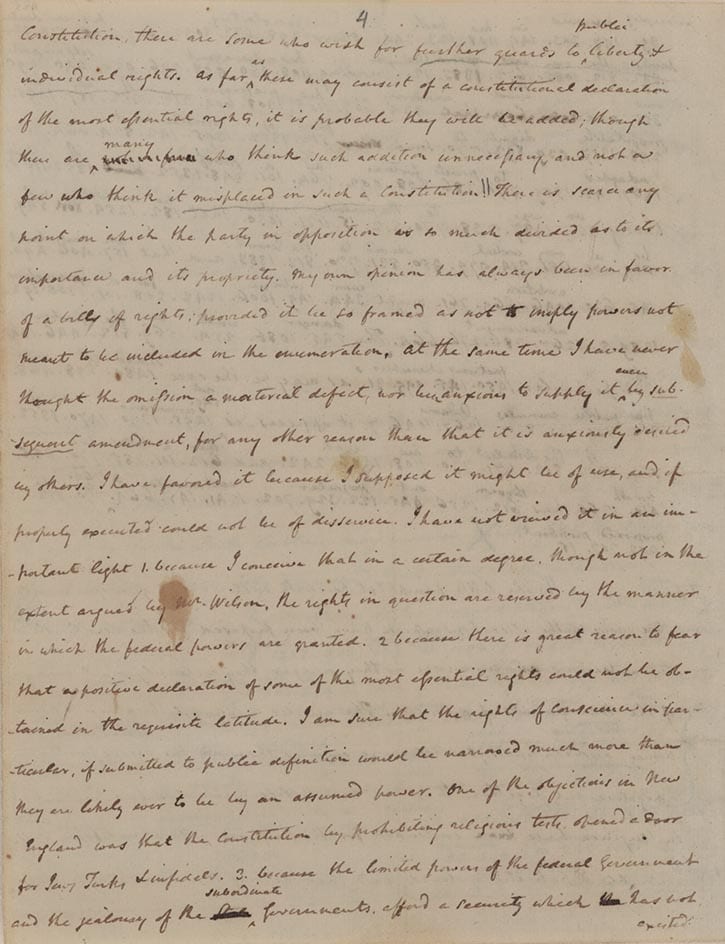

NEW YORK, October 17, 1788

Madison tells Jefferson that both John Hancock and John Adams are objectionable as candidates for the vice presidency. He reiterates his point that the alterations to the Constitution should be friendly and should be handled by the First Congress. He expresses his prudential support for a bill of rights while restating that the danger to individual rights comes from popular majorities.

The States which have adopted the new Constitution are all proceeding to the arrangements for putting it into action in March next. Pennsylvania alone has as yet actually appointed deputies; and that only for the Senate. My last mentioned that these were Mr. R Morris and a Mr. McClay. How the other elections there and elsewhere will run is a matter of uncertainty. The Presidency alone unites the conjectures of the public. The vice president is not at all marked out by the general voice. As the President will be from a Southern State, it falls almost of course for the other part of the Continent to supply the next in rank. South Carolina may however think of Mr. Rutledge unless it should be previously discovered that votes will be wasted on him. The only candidates in the Northern States brought forward with their known consent are Hancock and Adams and between these it seems probable the question will lie. Both of them are objectionable and would I think be postponed by the general suffrage to several others if they would accept the place. Hancock is weak, ambitious, a courtier of popularity given to low intrigue and lately reunited by a factious friendship with S. Adams.

J. Adams has made himself obnoxious to many particularly in the Southern states by political principles avowed in his book. Others recollecting his cabal during the war against General Washington, knowing his extravagant self importance and considering his preference of an unprofitable dignity to some place of emolument better adapted to private fortune as a proof of his having an eye to the presidency conclude that he would not be a very cordial second to the General and that an impatient ambition might even intrigue for a premature advancement. The danger would be the greater if particular factious characters, as may be the case, should get into the public councils. Adams it appears, is not unaware of some of the obstacles to his wish and through a letter to Smith has thrown out popular sentiments as to the proposed president.

The little pamphlet herewith enclosed will give you a collective view of the alterations which have been proposed for the new Constitution. Various and numerous as they appear they certainly omit many of the true grounds of opposition. The articles relating to Treatises, to paper money, and to contracts, created more enemies than all errors in the System positive and negative put together. It is true nevertheless that not a few, particularly in Virginia have contended for the proposed alterations from the most honorable and patriotic motives; and that among the advocates for the Constitution there are some who wish for further guards to public liberty and individual rights. As far as these may consist of a constitutional declaration of the most essential rights, it is probable they will be added; though there are many who think such addition unnecessary, and not a few who think it misplaced in such a Constitution. There is scarce any point on which the party in opposition is so much divided as to its importance and its propriety.

My own opinion has always been in favor of a bill of rights; provided it be so framed as not to imply powers not meant to be included in the enumeration. At the same time I have never thought the omission a material defect nor been anxious to supply it even by subsequent amendment, for any other reason than that it is anxiously desired by others. I have favored it because I supposed it might be of use, and if properly executed could not be of disservice.

I have not viewed it in an important light 1. Because I conceive that in a certain degree, though not in the extent argued by Mr. Wilson, the rights in question are reserved by the manner in which the federal powers are granted. 2. Because there is great reason to fear that a positive declaration of some of the most essential rights could not be obtained in the requisite latitude. I am sure that the rights of conscience in particular, if submitted to the public definition would be narrowed much more than they are likely ever to be by an assumed power. One of the objections in New England was that the Constitution by prohibiting religious tests opened a door for Jews, Turks and infidels. 3. Because the limited powers of the federal Government and the jealousy of the subordinate Governments, afford a security which has not existed in the case of the State Governments, and exists in no other. 4. Because experience proves the inefficacy of a bill of rights on those occasions when its control is most needed. Repeated violations of these parchment barriers have been committed by overbearing majorities in every State. In Virginia I have seen the bill of rights violated in every instance where it has been opposed to a popular current. Notwithstanding the explicit provision contained in that instrument for the rights of Conscience it is well known that a religious establishment would have taken place and on narrower ground than was then proposed, notwithstanding the additional obstacle which the law has since created. Wherever the real power in a Government lies, there is the danger of oppression.

In our Governments the real power lies in the majority of the Community, and the invasion of private rights is chiefly to be apprehended, not from acts of Government contrary to the sense of its constituents, but from acts in which the Government is the mere instrument of the majority of the constituents. This is a truth of great importance, but not yet sufficiently attended to: and is probably more strongly impressed on my mind by facts, and reflections suggested by them, than on yours which has contemplated abuses of power issuing from a very different quarter. Wherever there is an interest and power to do wrong, wrong will generally be done, and not less readily by a powerful and interested party than by a powerful and interested prince. The difference, so far as it relates to the superiority of republics over monarchies, lies in the less degree of probability that interest may prompt abuses of power in the former than in the latter; and in the security in the former against oppression of more than the smaller part of the Society, whereas in the latter it may be extended in a manner to the whole. The difference so far as it relates to the point in question-the efficacy of a bill of rights in controlling abuses of power-lies in this: that in a monarchy the latent force of the nation is superior to that of the Sovereign, and a solemn charter of popular rights must have a great effect, as a standard for trying the charter of popular rights must have a great effect, as a standard for trying the validity of public acts, and a signal for rousing and uniting the superior force of the community; whereas in a popular Government, the political and physical power may be considered as vested in the same hands, that is in a majority of the people, and consequently the tyrannical will of the sovereign is not to be controlled by the dread of an appeal to any other force within the community.

What use then it may be asked can a bill of rights serve in popular Governments? I answer the two following which though less essential than in other Governments, sufficiently recommend the precaution. 1. The political truths declared that in solemn manner acquire by degrees the character of fundamental maxims of free Government, and as they become incorporated with the national sentiment, counteract the impulses of interest and passion. 2. Although it be generally true as above stated that the danger of oppression lies in the interested majorities of the people rather than in usurped acts of the Government, yet there may be occasions on which the evil may spring from the latter sources; and on such, a bill of rights will be a good ground for an appeal to the sense of the community. Perhaps too there may be a certain degree of danger, that a succession of artful and ambitious rulers, may by gradual and well-timed advances, finally erect an independent Government on the subversion of liberty. Should this danger exist at all, it is prudent to guard against it, especially when the precaution can do no injury. At the same time I must own that I see no tendency in our governments to danger on that side. It has been remarked that there is a tendency in all Governments to an augmentation of power at the expense of liberty. But the remark as usually understood does not appear to me well founded. Power when it has attained a certain degree of energy and independence goes on generally to further degrees. But when below that degree, the direct tendency is to further degrees of relaxation, until the abuses of liberty beget a sudden transition to an undue degree of power. With this explanation the remark may be true; and in the latter sense only is it in my opinion applicable to the Governments in America. It is a melancholy reflection that liberty should be equally exposed to danger whether the Government have too much or too little power; and that the line which divides these extremes should be so inaccurately defined by experience.

Supposing a bill of rights to be proper the articles which ought to compose it, admit of much discussion. I am inclined to think that absolute restrictions in cases that are doubtful, or where emergencies may overrule them, ought to be avoided. The restrictions however strongly marked on paper will never be regarded when opposed to the decided sense of the public; and after repeated violations in extraordinary cases, they will lose even their ordinary efficacy. Should a Rebellion or insurrection alarm the people as well as the Government, and a suspension of the habeas corpus be dictated by the alarm, no written prohibitions on earth would prevent the measure. Should an army in time of peace be gradually established in our neighborhood by Britain or Spain, declarations on paper would have as little effect in preventing a standing force for the public safety. The best security against these evils is to remove the pretext for them.

With regard to Monopolies they are justly classed among the greatest nuisances in Government. But is it clear that as encouragements to literary works and indigenous discoveries, they are not too valuable to be wholly renounced? Would it not suffice to reserve in all cases a right to the public to abolish the privilege at a price to be specified in the grant of it? Is there not also infinitely less danger of this abuse in our Governments than in most others? Monopolies are sacrifices of the many to the few. Where the power is in the few it is natural for them to sacrifice the many to their own partialities and corruptions. Where the power, as with us, in the many not in the few, the danger cannot be very great that the few will be thus favored. It is much more to be dreaded that the few will be unnecessarily sacrificed to the many.

Jefferson to Madison

November 18, 1788

Jefferson considers The Federalist “the best commentary on the principles of government which was ever written.”

With respect to the Federalist, the three authors had been named to me. I read it with care, pleasure and improvement, and was satisfied there was nothing in it by one of those hands, and not a great deal by a second. It does the highest honor to the third, as being, in my opinion, the best commentary on the principles of government which was ever written. In some parts it is discoverable that the author means only to say what may be best said in defense of opinions in which he did not concur. But in general it establishes firmly the plan of government. I confess it has rectified me in several points. As to the bill of rights however I still think it should be added, and I am glad to see that three states have at length considered the perpetual re-eligibility of the president as an article which should be amended. I should deprecate with you indeed the meeting of a new convention. I hope they will adopt the mode of amendment by Congress and the Assemblies, in which case I should not fear any dangerous innovation in the plan. But the minorities are too respectable not to be entitled to some sacrifice of opinion in the majority. Especially when a great proportion of them would be contented with a bill of rights.

Here things internally are going on well. The Notables, now in session, have indeed past one vote which augurs ill to the rights of the people. But if they do not obtain now so much as they have a right to, they will in the long run. The misfortune is that they are not yet ripe for receiving the blessings to which they are entitled. I doubt, for instance, whether the body of the nation, if they could be consulted, would accept of a Habeas corpus law, if offered them by the king. If the Etats General, when they assemble, do not aim at too much, they may begin a good constitution. There are three articles which they may easily obtain. 1. Their own meeting periodically. 2. The exclusive right of taxation. 3. The right of registering laws and proposing amendments to them as exercised not by the parliaments. This last would be readily approved by the court on account of their hostility against the parliaments, and would lead immediately to the origination of laws. The 2d. has been already solemnly avowed by the king: and it is well understood there would be no opposition to the first. If they push at much more, all may fail. I shall not enter further into public details, because my letter to Mr. Jay will give them. That contains a request of permission to return to America the next spring, for the summer only.…

Supposing that the funding their foreign debt will be among the first operations of the new government, I send you two estimates, the one by myself, the other by a gentleman infinitely better acquainted with the subject, showing what fund will suffice to discharge the principal and interest as it shall become due, aided by occasional loans, which the same fund will repay. I enclose them to you, because collating them together, and with your own ideas, you will be able to devise something better than either. But something must be done. This government will expect, I fancy, a very satisfactory provision for the payment of their debt, from the first session of the new Congress. Perhaps in this matter, as well as the arrangement of your foreign affairs, I may be able, when on the spot with you, to give some information and suggest some hints, which may render my visit to my native country not altogether useless. I consider as not small advantage the resuming the tone of mind of my constituents, which is lost by long absences, and can only be recovered by mixing with them: and shall particularly hope for much profit and pleasure, by contriving to pass as much time as possible with you.…

Madison to Jefferson

PHILADELPHIA, December 8, 1788

Madison hopes and expects “a spirit of conciliation” shall prevail in the First Congress.

Not withstanding the formidable opposition made to the new federal government, first in order to prevent its adoption, and since in order to place its administration in the hands of disaffected men, there is now both a certainty of its peaceable commencement in March next, and a flattering prospect that it will be administered by men who will give it a fair trial. General Washington will certainly be called to the Executive department. Mr. Adams who is pledged to support him will probably be the best vice president. The enemies to the Government, at the head and the most inveterate of whom, is Mr. Henry are laying a train for the election of Governor Clinton, but it cannot succeed unless the federal votes be more dispensed than can well happen. Of the seven States which have appointed their Senators, Virginia alone will have anitfederal members in that branch. Those of N. Hampshire are President Langdon and Judge Bartlett of Massachusetts Mr. Strong and Mr. Dalton, of Connecticut Doctor. Johnson and Mr. Ellsworth, of N. Jersey Mr. Patterson and Mr. Elmer, of Penna. Mr. R. Morris and Mr. McClay, of Delaware Mr. Geo: Reed and Mr. Bassett, of Virginia Mr. R. H. Lee and Col. Grayson. Here is already a majority of the ratifying States on the side of the Constitution. And it is not doubted that the appointments of Maryland, S. Carolina and Georgia will reinforce it. As one branch of the Legislature of N. York is attached to the Constitution, it is not improbable that one of the Senators from that State also will be added to the majority.

In the House of Representatives the proportion of antifederal members will of course be greater, but cannot if present appearances are to be trusted amount to a majority or even a very formidable minority. The election for this branch has taken places as yet nowhere except in Penna. and here the returns are not yet come in from all the Counties. It is certain however that seven out of the eight, and probably that the whole eight representatives will bear the federal stamp. Even in Virginia where the enemies to the Government form 2/3 of the legislature it is computed that more than half the number of Representatives, who will be elected by the people, formed into districts for the purpose, will be of the same stamp. By some it is computed that 7 out of the 10 allotted to that State would be opposed to the politics of the present Legislature.

The questions which divide the public at present relate 1. to the extent of the amendments that ought to be made to the Constitution, 2. to the mode in which they ought to be made. The friends of the Constitution, some from an approbation of particular amendments, others from a sprit of conciliation, are generally agreed that the System should be revised. But they wish the revisal to be carried no farther than to supply additional guards for liberty, without abridging the sum of power transferred from the States to the general Government, or altering previous to trial, the particular structure of the latter and are fixed in opposition to the risk of another Convention, whilst the purpose can be as well answered, by the other mode provided for introducing amendments. Those who have opposed the Constitution, are on the other hand, zealous for a second Convention, and for a revisal which may either not be restrained at all, or extend at least as far as alterations have been proposed by any State. Some of this class are, no doubt, friends to an effective Government, and even to the substance of the particular Government in question. It is equally certain that there are others who urge a second Convention with the insidious hope of throwing all things into Confusion, and of subverting the fabric just established, if not the Union itself. If the first Congress embrace the policy which circumstances mark out, they will not fail to propose themselves, every desirable safeguard for popular rights; and by thus separating the well meaning from the designing opponents fix on the latter their true character and give to the Government its due popularity and stability.”

Madison to Jefferson

December 12, 1788

Madison is pleased that the results of the recent general election in Virginia to the First Congress mean that 1) a second Grand Convention is unlikely and 2) prudential rather than dangerous alterations to the Constitution shall be passed.

There will be seven representatives of the federal party, and one a moderate antifederalist. I consider this choice as ensuring a majority of friends to the federal Constitution, in both branches of the Congress; as securing the Constitution against the hazardous experiment of a Second Convention; and if prudence should be the character of the first Congress, as leading to measures which will conciliate the well-meaning of all parties, and put our affairs into an auspicious train.

Jefferson to Madison

January 12, 1789

Jefferson indicates that France is experimenting with “forming a declaration of rights.”

Every body here [France] is trying their hands at forming declarations of rights. As something of that kind is going on with you also, I send you two specimens from hence. The one is by our friend of whom I have just spoken. You will see that it contains the essential principles of ours accommodated as much as could be to the actual state of things here. The other is from a very sensible man, a pure theorist, of the sect called the economists, of which Turgot was considered the head. The former is adapted to the existing abuses; the latter goes to those possible as well as to those existing.

Jefferson to Madison

PARIS, March 15, 1789

Jefferson provides four “short answers” to Madison’s October 17th, 1788 letter where he expresses a prudential, rather than a robust principled place, for a bill of rights within the new American system.

Your thoughts on the subject of the declaration of rights in the letter of October the 17th, I have weighed with great satisfaction. Some of them had not occurred to me before, but were acknowledged just in the moment they were presented to my mind.

In the arguments in favor of a declaration of rights, you omit one which has great weight with me; the legal check which it puts into the hands of the judiciary. This is a body, which, if rendered independent, and kept strictly to their own department, merits great confidence for their learning and integrity. In fact, what degree of confidence would be too much, for a body composed of such men as Wythe, Blair, and Pendleton? On characters like these, the “civium ardor prava jubentium” [Editor’s Note. “wayward ardor of the ruling citizens.”] would make no impression. I am happy to find that on the whole you are a friend to this with some inconveniences, and not accomplishing fully its object.

But the short answers to the objections which your letter states to have been raised.

1. That the rights in question are reserved by the manner in which the federal powers are granted. Answer. A constitutive act may certainly be so formed as to need no declaration of rights. The act itself has the force of a declaration as far as it goes: and if it goes to all material points nothing more is wanting. In the draught of a constitution which I had once a thought of proposing in Virginia, and printed afterwards, I endeavored to reach all the great objects of public liberty and did not mean to add a declaration of rights. Probably the object was imperfectly executed: but the deficiencies would have been supplied by others in the course of discussion. But in a constitutive act which leave some precious articles unnoticed, and raises implications against others, a declaration of rights becomes necessary by way of supplement. This is the case of our new federal constitution. This instrument forms us into one state as to certain objects, and gives us a legislative and executive body for these objects. It should therefore guard us against their abuses of power within the field submitted to them.

2. A positive declaration of some essential rights could not be obtained in the requisite latitude. Answer. Half a loaf is better is better than no bread. If we cannot secure all our rights, let us secure what we can.

3. The limited powers of the federal government and jealousy of the subordinate governments afford a security which exists in no other instance. Answer. The first member of this seems resolvable into the 1st. objection before stated. The jealousy of the subordinate governments is a precious reliance. But observe that those governments are only agents. They must have principles furnished them whereon to found their opposition. The declaration of rights will be the next whereby they will try all the acts of the federal government. In this view it is necessary to the federal government also: as by the same text they may try the opposition of the subordinate governments.

4. Experience proves the inefficacy of a bill of rights. True. But though it is not absolutely efficacious under all circumstances, it is of great potency always, and rarely inefficacious. A brace the more will often keep up the building which would have fallen with that brace the less.

There is a remarkable difference between the characters of the inconveniencies which attend a Declaration of rights, and those which attend the want of it. The inconveniences of the Declaration are that it may cramp government in it’s useful exertions. But the evil of this is short lived, moderate, and reparable. The inconveniences of the want of a Declaration are permanent, afflicting and irreparable: they are in constant progression from bad to worse. The executive in our governments is not the sole, it is scarcely the principal object of my jealousy. The tyranny of the legislatures is the most formidable dread at present, and it will be for long years. That of the executive will come in it’s turn, but it will be at a remote period. I know there are some among us who would now establish a monarchy. But they are inconsiderable in number and weight of character. The rising race are all republicans. We were educated in royalism: no wonder if some us retain that idolatry still. Our young people are educated in republicanism. An apostasy from that to royalism is unprecedented and impossible.

I am much pleased with the prospect that a declaration of rights will be added: and hope it will be done in that way which will not endanger the whole frame of the government, or any essential part of it.…)