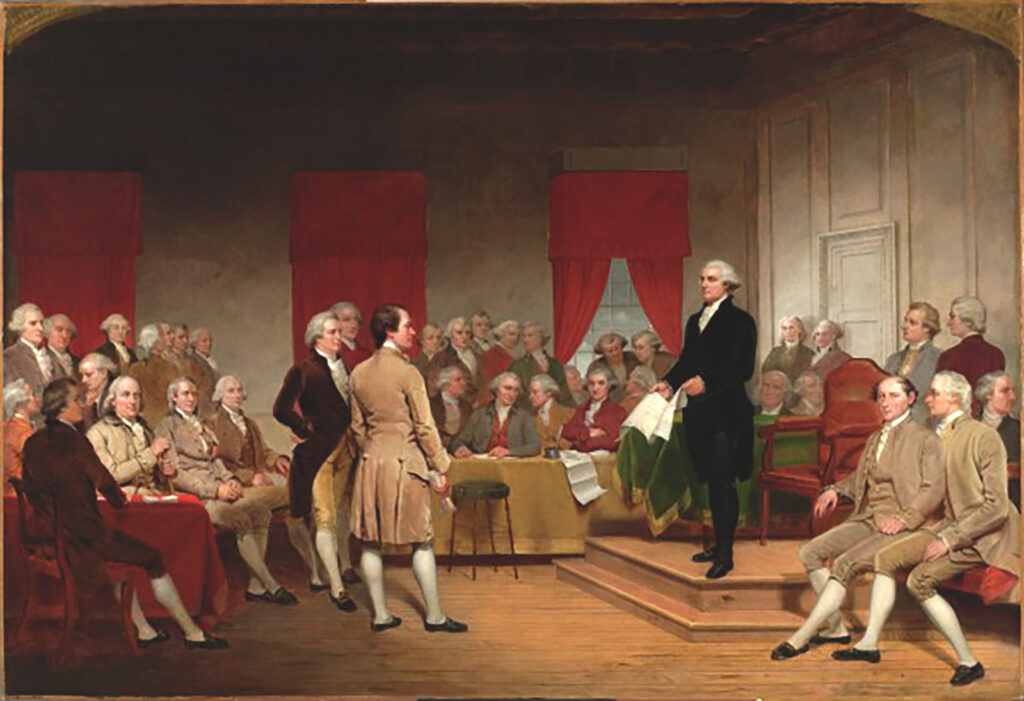

by Junius Brutus Stearns

Artist’s Biography

Junius Brutus Stearns was born Lucius Sawyer Stearns in Vermont in 1810. He took a new name after disagreeing with his father about his choice of career. He was a pupil at, and later member of, the Council of the National Academy of Design in New York, where he served as recording secretary from 1851 to 1865. Stearns died in Brooklyn, New York in 1885. The New York Times, September 19, 1885, reported that he died as result of a head-on carriage accident after a night at the theater.

Stearns is best known for his Washington Series, 1847-1856, in which he presents George Washington in five scenes from his life: just before reorganizing the retreat from the Battle of Monongahela during the French and Indian War; marrying Martha Custis; supervising his plantation after his retirement from the Presidency; dying as a Christian, surrounded by family and friends; — and presiding over the Constitutional Convention.

The Painting

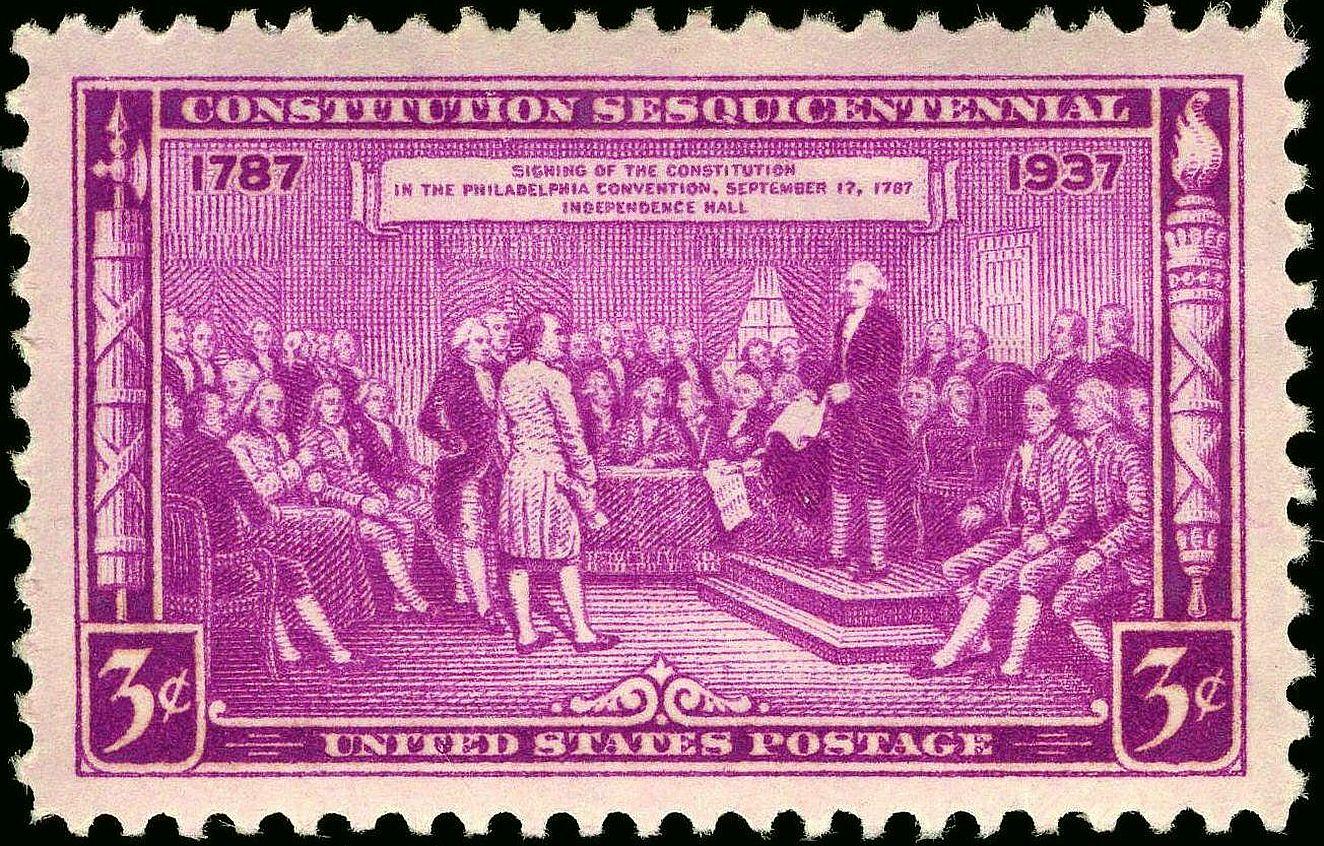

Washington as Statesman at the Constitutional Convention, a three by four and a half foot oil on canvas, was painted in 1856, after Stearns completed the other four paintings in the series. Stearns’ “Statesman” painting was reproduced on a three-cent commemorative postage stamp in September 1937, first issued in Philadelphia on the 17th of September, to honor the 150th anniversary of the Signing of the Constitution.

Stearns vs. Christy

We might view Stearns’ depiction of the signing of the Constitution as a precursor of the famous Christy “Signing” painting of the twentieth century, commissioned by Congress in 1939, during its observance of the 150th anniversary of the the Constitution’s ratification. Stearns’ painting was the first large-scale depiction of the activities of the Constitutional Convention. Forty years earlier, Congress had commissioned John Trumbull to paint the signing of the Declaration, and other artists had completed individual portraits of the Founders that were readily known and accessible. The convention, by contrast, prior to Stearns’ painting, had been portrayed only in small drawings, such as an engraving by Elkanah Tisdale in 1823.

Both Stearns and Christy are concerned to represent all of the signers. In “Statesmanship,” Stearns portrays the 39 delegates whose names appear on the Constitution, although on September 17, 1787, only thirty-eight delegates were actually in attendance. John Dickinson of Delaware was indisposed, so George Read, also of Delaware, signed Dickinson’s name. Christy makes a similar choice, parking Dickinson in the upper right portion of his painting, and even painting the Secretary of the Convention, William Jackson, placing him in a prominent position.

In support of this interpretation that Stearns’s painting informs Christy’s version of the Signing, take a look at the curtains. One set are closed and one set are open, indicating the movement from a deliberation in secret for over four months to a decision in the light of day. Christy has both curtains open, indicating that the signing has occurred. Stearns, like Christy, also has one delegation sitting around a table — in fact, both painters have one, and only one, delegation sitting at a table. Stearns seems to portray an earlier plan for the Constitution sliding off the table and onto the floor, in contrast to the one Washington is presenting to the delegates for signing. Likewise, Christy shows crumpled paper on the floor. Thus, I think it not unreasonable to presume that the frustrated folks sitting at the table for both Stearns and Christy are Roger Sherman and William Johnson, of the Connecticut delegation.

Why the tiny black slippers for the delegates, as opposed to black boots for the General? Stearns gives prominence to Washington, painting him as taller than anyone else, raised above everyone else, more illuminated than anyone else, and clearly more identifiable than anyone else. He shows Washington as “in charge.” Christy similarly makes Washington prominent, surrounded by the Rising Sun chair and all sorts of American flags to add to the celebrations. Unlike the Christy painting, however, where all the delegates can be identified, one has to work very hard to identify delegates other than Washington in Stearns’ work. Washington is truly an icon par excellence for Stearns. (Indeed, a reverence for Washington above all the other founders persisted through the Great Depression and the Second World War for many Americans. In fact, a majority of Americans had a commemorative symbol of Washington in their homes up through World War II.)

The Delegates

Stearns groups the delegates into five clusters, suggesting he may have intended to indicate distinct interest groups at the Convention. We can venture only general guesses as to the identity of the delegates in most of the groups. The first “group” is Washington, who stands by himself. A second group of three stands in front of Washington. Who are these delegates? Behind these three, at the left of the painting, are thirteen delegates, making up the third group. Four of this group are sitting in chairs, and nine are standing behind them. Franklin and Madison are recognizable in the front row of the four delegates who are sitting. And all thirteen of this group look pretty satisfied and content with the outcome.

Between Washington and the second group of three, Stearns depicts, in the background and situated to the right of him, thirteen delegates. Two or three of this group are sitting around the table mentioned above, while the remainder are standing and chatting. This fourth group of thirteen does not look as content as the thirteen men in the third group. Who are these delegates, and why do they seem a bit grim? Finally, nine delegates, all situated behind Washington, make up the fifth and final group. Four of them are sitting and five are standing. Who are these nine delegates?